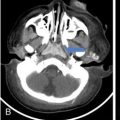

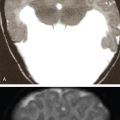

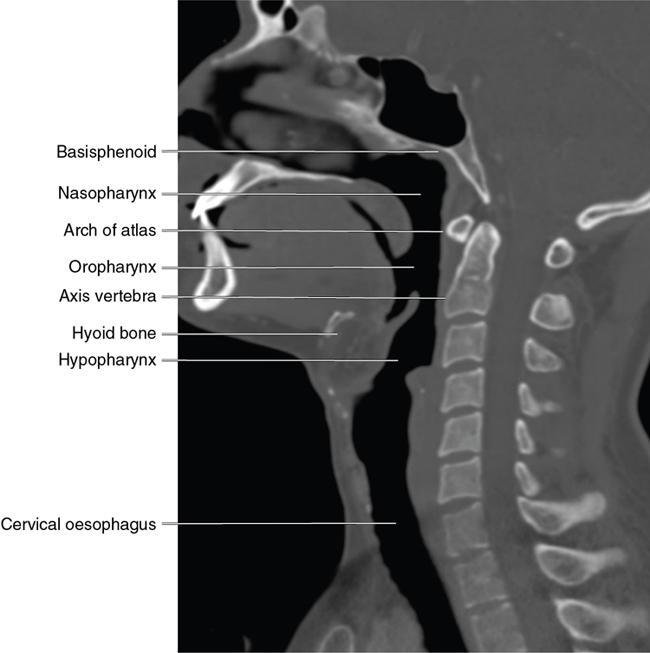

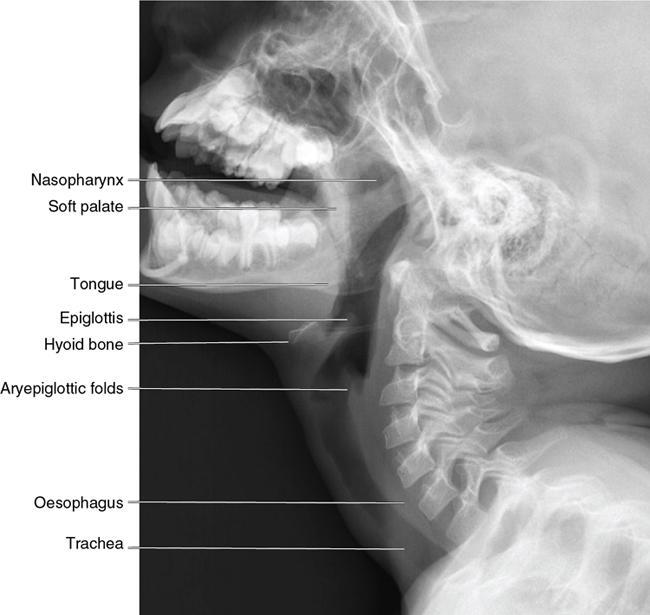

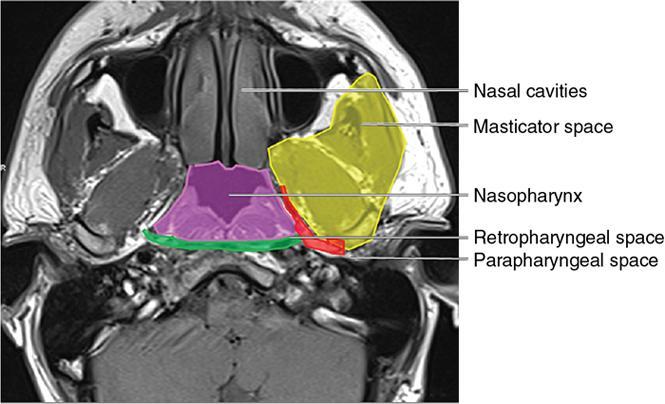

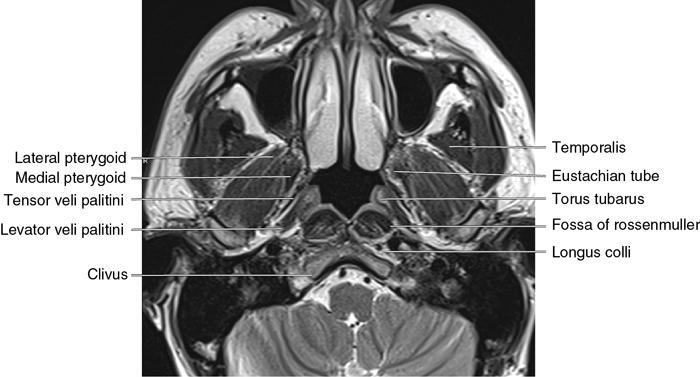

Saugata Sen, Anisha Gehani, Jeevitesh Khoda, Dayananda Lingegowda Physical and naked eye examination of the nasopharyngeal region is not possible. Endoscopy and cross-sectional imaging are the only tools available for evaluating lesions in this region. Proximity to the skull base makes imaging an interesting and important proposition in the management protocol of nasopharyngeal lesions. Direct and indirect involvement of the nervous system and skull base demands diagnostic precision. Management varies according to the various diseases that occur in this region, and the skills of a radiologist are important for a planning treatment and prognostication. In this chapter, we shall discuss the radiological anatomy of the nasopharynx and the pathologies that occur in this region. We will also go through the radiology of the common pathologies and discuss staging of malignant lesions. Imaging of treatment response and recurrence will be emphasized. We will also devote a small section for special consideration of imaging on diseases of paediatric and young adults. The cranial most part of the pharynx is the nasopharynx. It lies just below the middle cranial fossa. The nasopharynx is a musculofascial columnar tube with an inner mucosal layer lining the airway. The nasopharyngeal epithelium is complex. Stratified squamous epithelium is present at the anterolateral walls and inferior anterior and inferior posterior walls. Ciliated columnar epithelium is present around the nasal choanae and the posterosuperior wall or roof. The remaining areas have a mixture of the aforementioned two types. An intermediate epithelium is also present in the nasopharynx at the junction of nasopharynx and oropharynx. Muscular and fascial layers are present deep to the mucosa. The buccopharyngeal fascia separates the pharynx from the retropharyngeal space and parapharyngeal space (Fig. 3.9.3). The longus capitis muscles lie posterior to the nasopharynx and retropharyngeal space. The strong musculofascial covering of the mucosa and epithelium serves several important functions. The strength of this covering maintains the contour and patency of the airway. The composite layer also prevents any disease process in the airway to extend into the deep spaces of the neck. The posterior relation of the nasopharynx is the longus colli muscles and the retropharyngeal space. The lateral relations are the parapharyngeal spaces. On the anterior aspect are the nasal cavities (Fig. 3.9.3). The skull base forms the superior relation. There are three anatomical components of the nasopharynx that are clinically relevant and deserve special mention (Fig. 3.9.4). Enlarged adenoid in adults should trigger search for infection and lymphoproliferative conditions. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma is another differential. The common diseases that are prevalent in the nasopharynx are mentioned in the following. Since NPC is the most important pathology in this region, we will discuss it first and then go on to describe the others. The incidence of NPC varies around the world and is common in certain ethnic groups. NPC is more prevalent in the Mongoloid population in China and Southeast Asia. The Arctic (Eskimos) and north African region are also endemic for this disease. This disease is pathologically a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), the peak incidence of which is in the fourth to fifth decades. The incidence ratio of males to females is 3:1. Though NPC is the most common malignant tumour of the nasopharynx, its incidence worldwide remains low at 0.7% of all cancers. The disparate geographic distribution suggests underlying genetic modification in certain ethnic groups that make them susceptible to NPS. Many factors have been incriminated for the etiopathogenesis of NPC which include genetic and environmental factors as well as infection. The disease is an interplay of several of these factors and they are listed in the following: Carcinogenesis of NPC demonstrates interplay of the aforementioned factors. It is highly possible that all or some of these factors are coconspirators in the etiopathogenesis and each is not singularly responsible for development of NPC. NPC is different from other carcinomas in the head and neck regions in epidemiological and histopathologic features. The management strategies and response to therapy are also very different from the other carcinoma of the head and neck regions. The histopathological classification of NPC as proposed by WHO is as follows: The endemic form of NPC that is largely prevalent in China, Southeast Asia, North Africa and the Arctics are EBV related and of the undifferentiated form of nonkeratinizing SCC. Clinical presentation of NPC varies from asymptomatic to nasal obstruction, change in voice, nasal bleed and neck adenopathy. In fact, the commonest cause of neck adenopathy in endemic populations is NPC. The physician depends only on endoscopy for evaluation of the nasopharynx. Nasal endoscopy is a great modality for diagnosis and sampling but underestimates the true extent of the tumour. Also, approximately 10% of nasopharyngeal cancers can be missed on endoscopy. For detection of small lesions, delineation of the exact extent and staging of the tumour as well as the nodes, some form of cross-sectional imaging is essential. The appropriate imaging modality in NPC depends on the clinical stage. Contrast-enhanced MRI (CEMRI) is usually the mainstay due to its ability to detect soft-tissue extension. Diagnostic precision is of paramount importance in this region to detect subtle cranial nerve involvement and skull base extension, both of which are served well by CEMRI. CEMRI is efficient in detecting lymph nodes in the neck as well. Posttreatment imaging is another scenario where CEMRI has been proven to be extremely reliable for diagnosing subtle residual disease or complete response. In the posttreatment setting, 18-FDG-PET-CT has also been used. NPC with nodes greater than 6 cm or nodes below the lower border of the cricoid cartilage is at high risk of metastatic disease. In this scenario, some form of whole-body imaging is required, and 18-FDG-PET-CT is appropriate. Use of 18-FDG-PET-CT has also been advocated in primary staging and to judge response. The recommendations for appropriate imaging in NPC are as follows:

3.9: Nasopharynx

Introduction

Anatomy of the nasopharynx

Boundaries of the nasopharynx

Pathologies in the nasopharynx

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma

Introduction

Pathology

Clinical presentation and appropriate imaging

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree