Neoplasms

Nerve Sheath Tumors (Neurofibroma, Schwannoma)

These two tumors together represent the most common primary neoplasm of the spine, as well as the most common intradural-extramedullary neoplasm (slightly more common than a meningioma). The peak incidence is the fourth to fifth decades, with neurofibromas much less common than schwannomas. Both are World Health Organization (WHO) grade I lesions. Multiple schwannomas in a child should raise the question of NF2. The most frequent symptoms are pain and radiculopathy. Schwannomas are usually solitary. They arise from the Schwann cells of the myelin sheath. They are well encapsulated, lobulated, compressing adjacent tissue without nerve invasion. Most schwannomas are intradural ( Fig. 3.134 ), a smaller percent have both intradural and extradural components (and are dumbbell in shape), and < 10% are entirely extradural. Neurofibromas are not encapsulated, contain Schwann cells, fibroblasts, and a matrix of collagen and myxoid material, enlarging the nerve itself and producing a fusiform appearance. Neurofibromas are commonly associated with NF1, particularly when multiple, but also occur sporadically. Plexiform neurofibromas in NF1 can have malignant degeneration in a small percent of cases.

CT depicts these lesions poorly, and is not the primary imaging modality (which is MR). Foraminal enlargement, erosion of the pedicles, thinning of lamina, and posterior vertebral scalloping are however well visualized. MR provides excellent delineation and localization of nerve sheath tumors ( Fig. 3.135 ). Schwannomas and neurofibromas both appear as solid well-circumscribed masses, with substantial overlap in imaging appearance. As with many lesions, both are most commonly slightly hypointense on T1- and slightly hyperintense on T2-weighted scans. Both lesions enhance post-contrast ( Fig. 3.136 ). Small cystic areas and/or a heterogeneous appearance either pre- or post-contrast favor slightly a schwannoma. Important for differential diagnostic purposes is that a lesion located within the neural foramen can be mistaken for a disk herniation, with contrast enhancement allowing differentiation.

Meningioma

Twenty-five percent of all intraspinal tumors are meningiomas, with this lesion second in incidence only to benign neural tumors. Meningiomas are usually solitary, with a peak age of incidence of 45 years. In terms of location, one-third are cervical ( Fig. 3.137 ) and two-thirds are thoracic ( Fig. 3.138 ). One to 3% of all meningiomas occur at the foramen magnum. Of enhancing extra-axial lesions in this specific location, three-fourths are meningiomas and one-fourth neurofibromas.

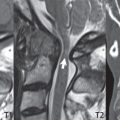

There is a 3:1 female:male incidence. An intradural location is most common, although meningiomas can be extradural. Meningiomas are benign tumors, histologically, slow growing, and cause symptoms due to cord and nerve root compression. Complete resection is achieved surgically in 95% of cases and, despite complete removal, 5% recur. On MR, pre-contrast, meningiomas are usually isointense to the cord on T1- and T2-weighted scans. Capping inferiorly and superiorly by CSF confirms the lesion to be intradural, extramedullary (by far the most common location) ( Fig. 3.139 ). Intense enhancement is seen post-contrast on MR. An enhancing dural tail is less common than intracranially. Dense calcification is often observed on CT in meningiomas, with the correlate on MR being a focal low signal intensity region within the lesion on both T1- and T2-weighted scans (which does not display contrast enhancement).

Ependymoma

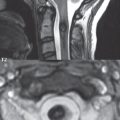

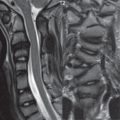

Ependymomas are the most common spinal cord tumor of adults, with a mean age at presentation of 40 years. It is a neuroepithelial tumor arising from the ependymal cells of the central canal. An important histologic variant is a myxopapillary ependymoma, which accounts for less than 20% of all ependymomas, but which is by far the dominant type at the conus and filum terminale (and in this location is extramedullary)—and which is also the most common tumor at this location ( Fig. 3.140 ). Ependymomas are usually low grade (WHO grade I and II). They are slow growing, well-circumscribed tumors with a tendency to compress adjacent neural tissue. On imaging, a small nodular, enhancing intramedullary lesion limited to two to three vertebral levels, with an accompanying cyst, favors the diagnosis of an ependymoma (as opposed to an astrocytoma). Hemorrhage does occur, and may produce superficial hemosiderosis involving the brainstem and lower cranial nerves, another differentiating feature. Complete surgical resection is possible. There is a very high incidence of ependymomas in NF2 patients. Ependymomas are usually well-delineated, and (disregarding the myxopapillary variant) are most common in the cervical region. On imaging, these are seen centrally within the cord, often with prominent enhancement ( Fig. 3.141 ). Reactive (nontumoral) cysts are common. Myxopapillary ependymomas may occasionally present as large lesions (scalloping the vertebral bodies), also typically display marked enhancement, and often have associated cystic components.

Astrocytoma

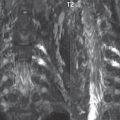

In children, spinal cord astrocytomas are more common than ependymomas, with ependymomas more common in adults. Cord astrocytomas are more likely to be low grade (WHO grade I and II) than higher grade. Clinical course parallels histologic grade. These infiltrative tumors are not amenable to surgical resection, unlike ependymomas. On imaging (MR), astrocytomas are characterized by a long segment of involvement (multiple vertebral segments), with near complete involvement of the width of the cord, poorly defined margins, and cord expansion ( Fig. 3.142 ). As with most tumors, the lesion will be of lower signal intensity than normal cord on T1-weighted scans, and of higher on T2-weighted scans. Contrast enhancement can be homogeneous, heterogeneous, seen only with delayed scans, or not present, and does not differentiate between tumor grades.

Hemangioblastoma

This tumor is the third most common intramedullary neoplasm of the spine, after ependymoma and astrocytoma. Hemangioblastomas can be solitary or multiple, the latter specifically with von Hippel-Lindau disease. These are slow growing lesions, generally diagnosed in adults. Hemangioblastomas are well-circumscribed, highly vascular (and thus with prominent enhancement on MR), small nodular lesions ( Fig. 3.143 ). On MR, there may be associated cord edema. In a minority of cases in the spine, a hemangioblastoma will lie along the wall of a large cyst. Prominent associated vessels are common, and can be visualized by contrast-enhanced MRA. Hemangioblastomas occur anywhere along the spinal cord, and in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease small nodular lesions can be seen along nerve roots as well ( Fig. 3.144 ).

Leptomeningeal and Spinal Cord Metastases

Contrast-enhanced MR is the most sensitive imaging modality for the detection of leptomeningeal metastases. CT myelography can demonstrate leptomeningeal seeding (as nodular filling defects), but is less sensitive and rarely employed. Although contrast enhancement on MR markedly improves detectability, abnormal enhancement is not seen in all instances. In areas of the spinal axis where the cord is present, the imaging appearance includes focal irregularity of the cord surface (tumor adherent to or encasing the cord) ( Fig. 3.145 ), a thin coating of the cord by tumor ( Fig. 3.146 ), and small focal nodules within the subarachnoid space. In the lumbar region, distal to the conus, the imaging appearance of leptomeningeal disease includes large and small nodules, and coating of nerve roots (which may appear “beaded” in appearance) ( Fig. 3.147 ). The entire spinal axis (cervical, thoracic, and lumbar regions) should be studied to rule out leptomeningeal involvement, with attention to the lumbar region. Due to the effect of gravity, if the patient is ambulatory, the disease as depicted by imaging may be restricted to the distal thecal sac ( Fig. 3.148 ).

Leptomeningeal metastases are seen with many different primary tumors, but in particular with (amongst CNS primary tumors) ependymoma and medulloblastoma and (of non-CNS tumors) lung carcinoma and breast carcinoma. The clinical presentation is varied, but includes pain, nerve deficits, and gait disturbance. The prognosis is poor. CSF cytology is the gold standard for diagnosis, but can require multiple samples and large volumes of CSF.

Spinal cord metastases are rare. Their appearance is nonspecific, that of a small focal mass lesion within the spinal cord, with associated vasogenic edema, that demonstrates contrast enhancement and causes mild focal cord expansion. Bronchogenic carcinoma is the most common primary.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree