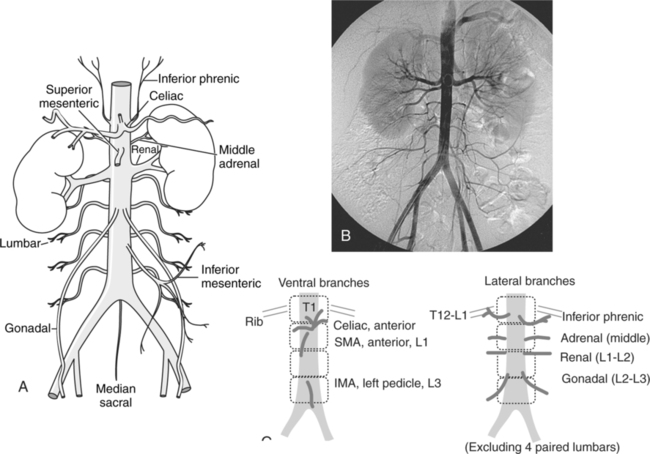

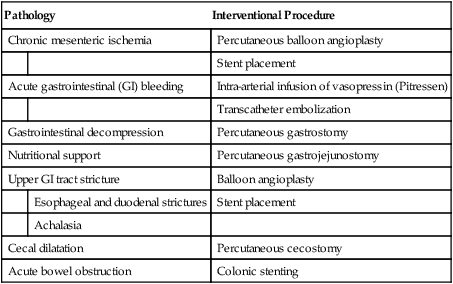

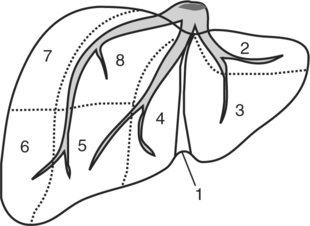

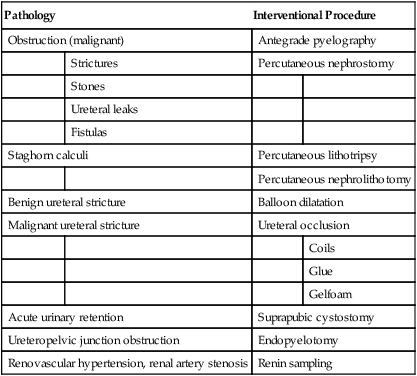

CHAPTER 19 After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to perform the following: The gastrointestinal system can be compared to a hollow tube that begins at the mouth and ends at the rectum. It consists of several accessory organs, notably the pancreas, gallbladder, liver, and salivary glands. It can be divided into an upper portion and a lower portion. Box 19-1 summarizes the components of each of the divisions. The blood supply for the abdominal viscera arises from the aorta as the celiac, superior, and inferior mesenteric arteries (Fig. 19-1). All these vessels are clearly demonstrated on an abdominal aortogram. Box 19-2 lists some of the disorders that can affect the GI system. In some cases therapies such as drug therapy, diet alteration, and stress reduction are successful; however, many pathologic conditions have been treated utilizing interventional techniques. Although the liver appears to be a single large structure, it has been described by Claude Couinaud, a French surgeon, as being segmental with each of the segments having its own outflow, inflow, and biliary drainage.1 He described eight areas according to a concept of plates and vasculobiliary sheaths (Fig. 19-2). The performance of the diagnostic and interventional procedures performed is dependent upon an accurate knowledge of the relationships between the intrahepatic ducts. A standard anatomic description is present in approximately 60% of individuals, and the physician must determine the exact nature of the patient’s anatomy in order to perform a successful procedure. Normally bile collects in the common bile duct until needed. Excess bile backs up the duct and enters the gallbladder, where it is stored and concentrated. In cases of blockage/obstruction of the ducts, bile accumulates in the liver, causing the bile salts and pigments to enter the bloodstream. This increase of bilirubin in the blood causes a condition referred to as jaundice. The body tissues become yellow as a result of the buildup of the pigments. One common reason for the blockage can be a large amount of fluid being absorbed from the bile or precipitation of the cholesterol in the bile. In both of these cases the result is the production of gallstones (biliary calculi), which can lodge in the ducts and create the blockage. Jaundice can be caused by other pathologic factors such as hepatitis, cirrhosis, trauma, biliary surgery, biliary cancer, tumors, and choledochal cysts. Box 19-3 summarizes the common interventions used to treat certain pathologic conditions affecting the biliary tract. Renin levels are usually checked by means of a blood test. This is known as a plasma renin activity (PRA) test and is usually done fasting. All medications must be discontinued for a period of 2 to 4 weeks. The normal values vary with age and body position. Renin collection can be accomplished by means of sampling directly from the renal vein. Usually, samples from both kidneys are taken and compared to determine which kidney is affected. Abnormal findings from the PRA test can indicate several pathologic conditions. Box 19-4 lists some of the conditions that can be diagnosed. Table 19-1 summarizes some of the currently applied nonvascular interventions for pathology of the urinary system. TABLE 19-1 Summary of Nonvascular Interventions of the Urinary System To successfully localize the lesion, the procedure must be guided. This guidance is accomplished with ultrasonography, CT, conventional fluoroscopy, or magnetic resonance imaging. These modalities are used alone or in combination to provide the maximum diagnostic information about the components of the lesion and its location. Each of the modalities has advantages and disadvantages. The choice of method depends on the physician’s preference, equipment availability, and hospital protocol. Box 19-5 provides a summary of the types of modalities and some of the anatomic areas where they have been used.

Nonvascular Interventional Procedures

Identify the anatomy and pathophysiology of the gastrointestinal system

Identify the anatomy and pathophysiology of the gastrointestinal system

Identify the anatomy and pathophysiology of the biliary system

Identify the anatomy and pathophysiology of the biliary system

Identify the anatomy and pathophysiology of the urinary system

Identify the anatomy and pathophysiology of the urinary system

Describe the general methodology used for needle biopsies

Describe the general methodology used for needle biopsies

Explain the general methodology of puncture and drainage procedures

Explain the general methodology of puncture and drainage procedures

Describe the general methodology for percutaneous calculi removal procedures

Describe the general methodology for percutaneous calculi removal procedures

Explain the general methodology of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

Explain the general methodology of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

ANATOMY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Gastrointestinal System

Accessory Organs

Urinary System

Pathology

Interventional Procedure

Obstruction (malignant)

Antegrade pyelography

Strictures

Percutaneous nephrostomy

Stones

Ureteral leaks

Fistulas

Staghorn calculi

Percutaneous lithotripsy

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy

Benign ureteral stricture

Balloon dilatation

Malignant ureteral stricture

Ureteral occlusion

Coils

Glue

Gelfoam

Acute urinary retention

Suprapubic cystostomy

Ureteropelvic junction obstruction

Endopyelotomy

Renovascular hypertension, renal artery stenosis

Renin sampling

GENERAL METHODOLOGY OF PROCEDURES

Needle Biopsy

Indications and Contraindications

Guidance Methods

Nonvascular Interventional Procedures