Case presentation

A 2-year-old male with a medical history of Hirschsprung disease requiring colectomy and ileo-anal pullthrough presents with multiple episodes of nonbilious emesis and no stool output over the past 24 hours. The mother states that she has noted that the child has had increased abdominal girth over the past 48 hours and has become fussy. He has had decreased oral intake. There has been no fever, cough, congestion, or diarrhea.

Shortly after birth, he underwent colectomy and ileostomy (which was taken down several months prior to his acute presentation). He has a chronic dysmotility disorder and is followed closely by Pediatric Gastroenterology. The mother has tried rectal dilatation and Miralax at home, per the child’s usual regimen when there is decreased stool output, without success. She has also noted no passage of flatus.

Physical examination reveals an interactive, non–toxic appearing, but visibly uncomfortable, child. He is afebrile. He has a heart rate of 130 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 24 breaths per minute, blood pressure of 93/54 mm Hg, and pulse oximetry of 99% on room air. His examination is remarkable for a moderately distended abdomen that does not appear to be tender. There is no organomegaly. Digital rectal examination results in an explosion of liquid, brown, nonbloody stool.

Imaging considerations

The location of the suspected obstruction will help the clinician determine which imaging modality to employ.

Plain radiography

This modality is often a first-line test and is rapidly available, requiring minimal exposure to ionizing radiation. Plain radiography can assist in the identification of the level of obstruction and can help guide the clinician in choosing more advanced imaging modalities, if indicated. , Bowel gas patterns can be associated with various pathologies: the “double bubble” sign of duodenal atresia, the “triple bubble” sign of proximal jejunal atresia, various abnormal patterns associated with meconium ileus, multiple air-filled loops of bowel with a lack of rectal gas in the infant with Hirschsprung disease, distended stomach in some infants with pyloric stenosis, radio-opaque foreign bodies, and a soft tissue mass effect on the right and lack of colonic air in some infants with intussusception. Perforation and free air can also be demonstrated. This is a primary value of plain abdominal radiography, but plain radiographs may vary and may even be normal in some pathologies, such as malrotation and volvulus.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is a first-line imaging modality for several causes of intestinal obstruction in pediatric patients, such as pyloric stenosis, intussusception, and pediatric appendicitis. , The usefulness of ultrasound to detect malrotation has been investigated. In this technique, the relationship of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) is evaluated. The SMA is normally to the left of the SMV. When the SMV is to the left of the SMA, the relationship of the vessels is inverted. It has been suggested that if this relationship is abnormal, the patient should undergo an upper gastrointestinal series (UGI) to confirm the presence or absence of malrotation. A study examining this relationship reported a false-positive rate of 21% (abnormal ultrasound and normal UGI) and a false-negative rate of 2% (normal ultrasound and abnormal UGI). , Another series found an abnormal relationship between these structures to have a sensitivity and specificity of 67% to 100% and 75% to 83% for malrotaion. Therefore, SMA/SMV inversion as a solitary finding is not highly sensitive or specific for malrotation. Additional sonographic signs that improve the value of ultrasound for malrotation include the “whirlpool sign,” where the mesentery and mesenteric vessels are wrapped around the SMA and SMV, and evaluation of whether the transverse duodenum is in a normal retroperitoneal position. When these two additional signs are evaluated in addition to SMA/SMV inversion, the sensitivity of ultrasound for malrotation is markedly improved, with one study showing a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of over 97% in the detection of malrotation. However, such an examination requires significant pediatric sonographic imaging expertise to perform and interpret and would find greatest utility in a facility with dedicated pediatric sonography.

Upper gastrointestinal series

This is the diagnostic test of choice in patients with suspected malrotation with or without volvulus as a cause of intestinal obstruction. False-positive and false-negative test results do occur, reported to be up to 15% and up to 6%, respectively, , so proper technique and expertise in imaging interpretation are essential to provide meaningful and accurate results.

Computed tomography (CT)

While not a typical first-line imaging test in children with suspected bowel obstruction, CT is useful at detecting such pathology. The pediatric literature is not as prolific compared to the adult literature investigating the use of CT in the diagnosis of intestinal obstruction. However, one study looking at small bowel obstruction reported a sensitivity of 87% and a specificity of 86% for detecting small bowel obstruction in pediatric patients (especially those over the age of 2 years); these percentages included patients with adynamic ileus, since this may be difficult to distinguish from bowel obstruction on CT. CT is also useful in detecting the level of obstruction (comparable to adult studies) in most patients (86%) but was not as useful in determining the cause of obstruction (54%). CT may be employed as a secondary test if other imaging modalities are equivocal or there is concern for a complex intra-abdominal process.

Imaging findings

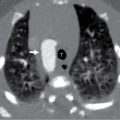

Plain radiography of the abdomen was obtained. These images demonstrated dilated small bowel loops in the upper abdomen without evidence of free air ( Figs. 15.1 and 15.2 ).

Case conclusion

Pediatric Surgery and Pediatric Gastroenterology were both consulted and the child was admitted to the pediatric hospitalist service for management of the obstruction. During his first hospital day, he underwent rectal dilatation and an SMOG (saline, mineral oil, glycerine) enema with a return of a very large amount of liquid stool. He improved after rectal dilatation and was ultimately discharged home.

Pediatric bowel obstruction has many causes and may present with a variety of symptoms, including acute abdominal pain, fussiness, vomiting, and shock, as well as having a more chronic presentation, as may be the case with partial or recurring episodes of obstruction. A thorough history and physical examination can guide the clinician in the investigation of a bowel obstruction as well as management. It may be helpful to think of the etiologies of neonatal and pediatric bowel obstruction by potential underlying causes. These include congenital, infective, traumatic, inflammatory, and neoplastic, among others. Consider the age of the patient, as certain causes of bowel obstruction occur more frequently in particular age groups.

Pediatric bowel obstruction has many causes and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality if these conditions are not detected and managed in a timely manner. As in adults, appendicitis and postoperative adhesions are causes of bowel obstruction in children. Children also experience bowel obstruction due to congenital and other pathologies not generally seen in adults. Causes of bowel obstruction in children also include the following:

Intestinal atresia

This is the most common cause of congenital intestinal obstruction and represents a large portion of neonatal obstruction cases. While mortality for this condition was significant (up to 90%), this has declined to around 10%. Duodenal atresia (often associated with an annular pancreas) and jejunoileal atresia can be seen in this age group and present as bilious emesis. The classic appearance of a “double bubble” on plain radiography suggests duodenal atresia. , Whether an imaging evaluation is indicated varies by suspected etiology and level of obstruction but, if indicated, should be performed by a pediatric radiologist or an imager with significant pediatric experience. Fluid resuscitation and surgical management are indicated for these patients.

Pyloric stenosis

Typically seen in the first 3–6 weeks of life, this is the most common cause of gastric outlet obstruction in this age group. A typical history consists of repeated episodes of nonbilious, “projectile” emesis with feeding. The often-cited electrolyte abnormalities include a hypochloremic, hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis. First-line imaging evaluation is a pyloric ultrasound. Fluid resuscitation, correction of metabolic derangements, and surgical consultation are cornerstones of management.

Malrotation with or without volvulus

The majority of pediatric patients with malrotation with or without volvulus will present in the first month of life, although this entity may present in older children, including teenagers. , First-line imaging evaluation is a fluoroscopic UGI series. Prompt recognition and surgical management are imperative in order to avoid significant morbidity and mortality associated with this condition.

Meconium ileus

While not commonly encountered in the emergency department, meconium ileus is significant due to its association with cystic fibrosis and pancreatic dysfunction. Children with cystic fibrosis may also have distal intestinal obstruction syndrome, constipation, megacolon, and rectal prolapse. Meconium ileus presents in the neonatal period, in the first couple days of life. Uncomplicated cases of meconium ileus are managed with supportive care and hyperosmolar enema; complicated cases should have pediatric surgical consultation and are usually managed with operative resection/anatamoses.

Intussusception

This is the most common cause of infant bowel obstruction and is usually found in children under the age of 6 years old. The underlying etiology of intussusception varies by age group: Infants and young children usually have “idiopathic” intussusceptions, with a lead point of inflamed intestinal lymphoid tissue, whereas older children often have a true lead point, such as a polyp, Meckel diverticulum or neoplastic process. First-line imaging for intussusception is ultrasound evaluation, but treatment for idiopathic intussusception is generally accomplished with an air enema. Children in extremis require fluid resuscitation, especially prior to any radiologic study or surgical intervention; these patients may require a pediatric surgical consult, particularly if the patient has had prolonged symptoms or there are signs of peritonitis.

Hirschsprung disease

In a patient with a history of delayed passage of meconium during the immediate postpartum period who presents with signs of bowel obstruction, the clinician should consider Hirschsprung disease as a possible etiology. This entity can be associated with other underlying medical conditions, such as Down syndrome. Imaging evaluation is performed with a water-soluble contrast enema. Until a patient is able to undergo surgical correction, bowel washouts are utilized in an attempt to keep the bowel decompressed.

Intestinal strictures

As a consequence of abdominal trauma, intestinal strictures have been reported and should be considered in a patient with a history of intestinal perforation or previous abdominal surgery. , Children with a history of blunt abdominal trauma who present with signs of bowel obstruction may have strictures or adhesions. Children with inflammatory bowel disease can also develop intestinal strictures and inflammatory masses involving affected portions of the bowel, both producing signs of bowel obstruction. Children with Crohn disease may require surgical intervention performed in cases of stricturing. Management involves consultation with pediatric surgery and pediatric gastroenterology for patients with complications from underlying inflammatory bowel disease.

Foreign body ingestions

The literature is replete with all manner of foreign bodies producing intestinal obstruction; children with pica or a history of developmental delay are at particular risk for foreign body ingestion. Plain radiography is the first-line imaging modality. Management depends on the type, quantity, and location of the foreign body and may be made in consultation with pediatric surgery and/or pediatric gastroenterology.

Intestinal tumors

Intestinal tumors are not common in children, but when present as a cause of intestinal obstruction, lymphoma is the dominant pathology. Management is directed at the underlying etiology of the tumor.

Omphalomesenteric remnants

A Meckel diverticulum can cause intestinal obstruction , and is a common congenital malformation of the gastrointestinal tract. Bowel obstruction is a common complication of Meckel diverticulum and can produce obstruction due to intussusception, adhesions, or volvulus. These complications can be detected with CT. Management includes consultation with pediatric surgery for surgical correction.

Several illustrative cases are provided here:

Figs. 15.3 and 15.4 show a 10-year-old female who presented with 1 day of rapidly progressive abdominal pain and distention, as well as emesis. Plain radiography of the abdomen demonstrated marked colonic distention. Pediatric Gastroenterology was consulted and the child was taken to the endoscopy suite, at which time a sigmoid volvulus identified and reduced successfully. Interestingly, this was the child’s third occurrence. Pediatric Surgery was consulted and the child was then taken to the operating suite for sigmoidectomy.