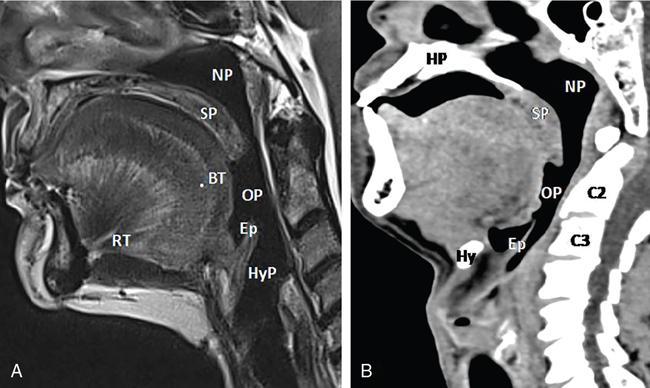

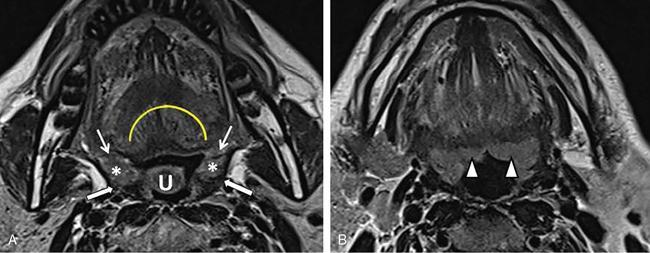

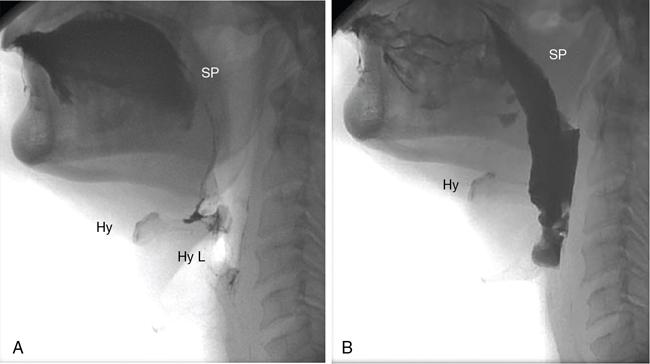

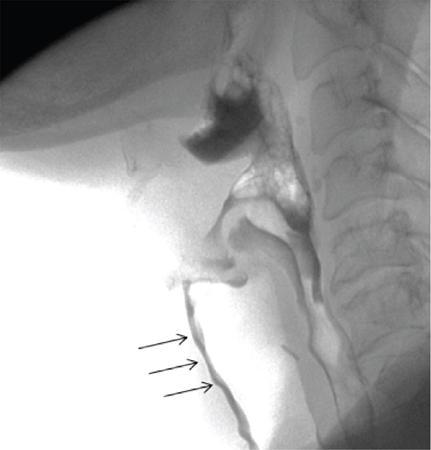

Saugata Sen, Anisha Gehani, Anmol Mohta, Bharat Gupta The oropharynx has several important functions and pathologies, making it a primary area of interest both to the physician and the radiologist. Being the gateway of the aerodigestive tract and exposed to the external environment directly, this region is the seat of both infection and malignancies. Prevention of regurgitation and swallowing are important physiologic functions of this region, and any deviation from normal can have morbid and mortal consequences. Imaging plays a pivotal role in demonstration of the normal and abnormal swallowing reflexes, in infections and malignancies. The oropharynx lies posterior to the oral cavity and in between the nasopharynx and velopharynx superiorly and the hypopharynx inferiorly. It is limited on its posterior aspect by the prevertebral fascia and retropharyngeal space. The anterior boundary of the oropharynx, i.e. the demarcation with the oral cavity, can be likened to a ring with the borders as mentioned in the following: Superiorly, the oropharynx is limited by the soft palate (elevated). The inferiorly, the superior margin of the epiglottis and vallecula limits the oropharyngeal boundary. On the posterior aspect, the retropharyngeal space, the prevertebral fascia and corresponding vertebral bodies of C2 and C3 are the relations of the oropharynx. On the lateral aspects on both sides are the tonsillar fossa containing the palatine tonsil. The tonsillar fossa is bound by anterior and posterior tonsillar pillars. The mucosa of the anterior tonsillar pillar covers the palatoglossus muscle, and that of the posterior tonsillar pillar covers the palatopharyngeus muscle (Table 3.10.1, Fig. 3.10.1A and B). The contents of the oropharynx are as follows: The mucosa and musculature of the oropharynx is covered by a visceral fascia, which acts as a barrier to spread of infection and tumour. Violation of this fascia leads to disease spread into the parapharyngeal and retropharyngeal spaces. Two important anatomical structures in the oropharynx need special mention (Fig. 3.10.2A–B). The palatine tonsils lie on either side of the oropharynx, between the anterior and posterior tonsillar pillars. They have multiple tiny openings on the surface called “pits”. These pits lead channels into the substance of the palatine tonsil opening up at “crypts”. The deeper aspect of the palatine tonsil is covered by a capsule. The palatine tonsil appears mildly hyperintense as compared with the tongue and adjoining structures on T2WI. The size of the palatine tonsil increases from 5 to 6 years up to 13–14 years of age. Postpuberty, the gland slowly involutes. Lingual tonsil is a patch of lymphoreticular tissue, analogous to the adenoid and tonsil, located at the base of the tongue. It has a midline groove and may extend up to the anterior wall of the vallecula. The lingual tonsil is mildly hyperintense as compared with the tongue on T2WI. The size of the lingual tonsil can vary from individual to individual. One must note that hypertrophy of the lingual tonsil can be a normal variant or a part of a generalized lymphoreticular disease and must be approached in perspective. A normally hypertrophied lingual tonsil should not extend beyond the anterior margin of the vallecula. If the floor or posterior borders of the vallecula are involved by the characteristic signal or density of the lingual tonsil, one must suspect beyond a normal variant and the lesion biopsied. The swallowing reflex is a key physiologic function of the oropharynx and has imaging implications. This is a complex process and occurs in tandem with the oral transport stage. On conclusion of the oral chewing process, the food bolus is propagated to the oropharynx by two mechanisms. The pressure that is generated by the mechanisms mentioned before pushes the food bolus backwards. The following processes happen together to propel the food into the oesophagus: By a complex neuromuscular coordinated movement, the food bolus reaches the upper oesophagus and the oesophageal stage begins. Thus, the oropharynx in particular and the pharynx in general play a key role in posterior and inferior propulsion of the food bolus. The coordinated movement also prevents nasal regurgitation of the bolus and aspiration. Both CT and MRI with intravenous contrast are excellent in assessing the oropharynx. Complementary information is provided by both these modalities, and many institutional protocols use them both together. MRI has the advantage of better soft-tissue resolution and can depict the local extension of disease as well as perineural spread. Diffusion-weighted MRI has evolved to provide functional information and can be very useful in confirming the malignant nature of disease as well as detecting posttreatment recurrence. Videofluoroscopy (VFS) is performed to assess functional abnormalities such as swallowing and dysphagia. It is a fluoroscopic procedure where images are captured at approximately 40 frames per second to assess the muscular movements and functions of the oropharynx. The food bolus is laced with thick barium paste for optimal visualization (Fig. 3.10.3A and B and Fig. 3.10.4). Carcinoma and lymphoma form the large majority of the neoplasms of the oropharynx. Rarely, minor salivary gland tumours and mesenchymal tumours may be encountered. Neoplastic lesions are among the commonest indications of imaging in the oropharynx. Oropharyngeal squamous cell cancers (OP-SCCs) account for over 90% of malignant lesions of this region. This is a disease of the elderly, whereby alcohol and tobacco use are most commonly incriminated. Over the past two decades, incidence of OP-SCC has been steadily increasing in the younger population, predominantly in the western world. This particular variant is driven by human papilloma viruss (HPV) infection. HPV-16 and HPV-18 are the responsible strains. HPV-driven OP-SCC has a predilection for the tongue base and the tonsillar fossa which have a typical reticulated epithelium within the crypts. The crypts lined by reticulated epithelium are immune challenged and fail to mount an immunological response to HPV infection. This particular phenomenon leads to HPV-related neoplastic processes in the tongue base and tonsillar fossa. In the aetiological context, one needs to be cognizant of the fact that HPV-driven OP-SCCs and non–HPV-driven OP-SCCs are different tumours. The HPV-driven OP-SCCs have a predilection for the tonsils and tonsillar fossa. HPV-driven OP-SCCs may be clinically occult and present with neck nodes, some of which may be cystic in nature. In HPV-associated OP-SCCs, cystic nodes are more common, and extranodal extension (ENE) of disease has no role to play in nodal staging. HPV-associated OP-SCC has a better prognosis and overall survival than the non-HPV type. Since the oral cavity and oropharynx are easily amenable to clinical examination, imaging modalities are not always called upon for the initial diagnosis. The primary role for radiology is staging the primary tumour as well as the nodes. Staging requires knowledge of the common local spread pattern and lymphatic drainage. The OP-SCC appears to be of intermediate signal intensity on T2W images. MRI appears to be the best modality for the oropharynx. This is because of the excellent soft-tissue resolution and multisequence capabilities such as fat suppression and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI). The region consists of numerous minor salivary glands that appear hyperintense on T2WI and show early contrast enhancement. As a result, one has to rely on T2WI and DWI for better delineation of tumour and its margins and extents, rather than the contrast sequences. Contrast-enhanced CT may also be used either on its own or as a complementary modality for imaging OP-SCC. The oropharynx has the following subsites:

3.10: Oropharynx

Introduction

Anatomy

Anterior

Oral cavity

Posterior

Posterior pharyngeal wall

Superior

Soft palate (elevated)

Inferior

Vallecula

Physiology

Imaging modalities

Pathology and imaging features

Neoplastic diseases

Oropharyngeal carcinoma

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree