Osteomyelitis, Infectious Arthritis, and Soft-Tissue Infections

Osteomyelitis

Osteomyelitis can generally be divided into pyogenic and nonpyogenic types. The former may be further classified, on the basis of clinical findings, as subacute, acute, or chronic (active and inactive), depending on the intensity of the infectious process and its associated symptoms. From the viewpoint of anatomic pathology, osteomyelitis can be divided into diffuse and localized (focal) forms, with the latter referred to as bone abscesses.

Pyogenic Bone Infections

Acute and Chronic Osteomyelitis

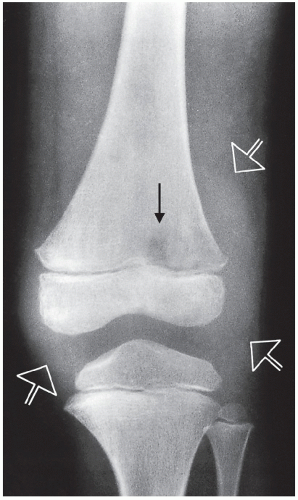

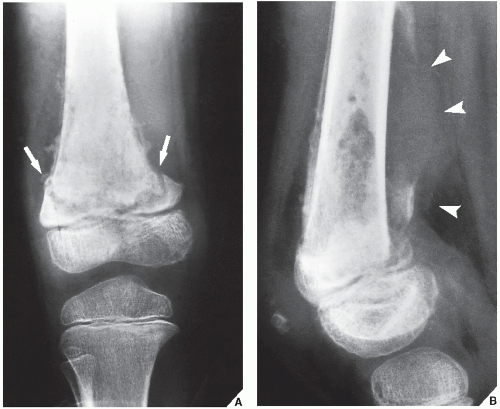

The earliest radiographic signs of bone infection are soft-tissue edema and loss of fascial planes. These are usually encountered within 24 to 48 hours of the onset of infection. The earliest changes in the bone are evidence of a destructive lytic lesion, usually within 7 to 10 days after the onset of infection (Fig. 25.1), and a positive radionuclide bone scan. Within 2 to 6 weeks, there is progressive destruction of cortical and medullary bone, an increased endosteal sclerosis indicating reactive new bone formation, and a periosteal reaction (Fig. 25.2). In 6 to 8 weeks, sequestra indicating areas of necrotic bone usually become apparent; they are surrounded by a dense involucrum, representing a sheath of periosteal new bone (Fig. 25.3). The sequestra, which can be effectively demonstrated with computed tomography (CT) (Fig. 25.4), and involucra develop as the result of an accumulation of inflammatory exudate (pus), which penetrates the cortex and strips it of periosteum, thus stimulating the inner layer to form new bone. The newly formed bone is in turn infected, and the resultant barrier causes the cortex and spongiosa to be deprived of a blood supply and to become necrotic. At this stage, termed chronic osteomyelitis, a draining sinus tract often forms (Fig. 25.5; see also Figs. 24.7 and 24.10B). Small sequestra are gradually resorbed, or they may be extruded through the sinus tract.

Subacute Osteomyelitis

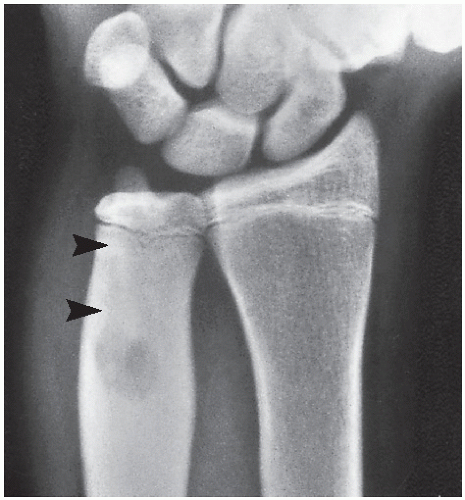

Brodie Abscess. This lesion, originally described by Brodie in 1832, represents a subacute localized form of osteomyelitis, commonly caused by Staphylococcus aureus. The highest incidence (approximately 40%) is in the second decade. More than 75% of cases occur in male patients. Its onset is often insidious, and systemic manifestations are generally mild or absent. The abscess, which is usually localized in the metaphysis of the tibia or femur, is typically elongated, with a well-demarcated margin and surrounded by reactive sclerosis. As a rule, sequestra are absent, but a radiolucent tract may be seen extending from the lesion into the growth plate (Fig. 25.6). A bone abscess may often cross the epiphyseal plate, but seldom does an abscess develop in and remain localized to the epiphysis (Fig. 25.7; see also Fig. 24.8).

Nonpyogenic Bone Infections

The most common nonpyogenic bone infections are tuberculosis, syphilis, and fungal infections.

Tuberculous Infections

Tuberculous bone infection usually occurs secondarily as a result of hematogenous spread from a primary focus of infection such as the lung or genitourinary tract. Skeletal tuberculosis represents approximately 3% of all cases of tuberculosis and approximately 30% of all extrapulmonary tuberculous infections. In 10% to 15% of cases, bone involvement without articular disease is encountered. In children, tuberculous osteomyelitis has a predilection for the metaphyseal segment of the long bones; in adults, the joints are more often affected.

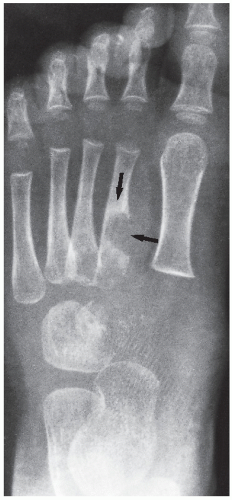

In the long and short bones, progressive destruction of the medullary region with abscess formation is apparent on radiography. Typically, there is evidence of osteoporosis but, at least in the early stage of the disease, little or no reactive sclerosis is usually present (Fig. 25.8). Occasionally, destruction in the mid diaphysis of a short tubular bone of the hand or foot (tuberculous dactylitis) may produce a fusiform enlargement of the entire diaphysis, a condition known as spina ventosa (Fig. 25.9). The appearance of multiple disseminated lytic lesions in short tubular bones is termed cystic tuberculosis, a form of skeletal tuberculosis seen particularly in children.

Fungal Infections

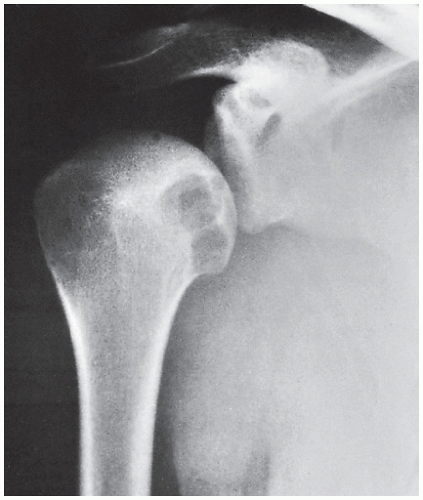

Fungal bone infections are infrequent, the most common being coccidioidomycosis, blastomycosis, actinomycosis, cryptococcosis, and nocardiosis. The infection is usually low grade, with the formation of an abscess and a draining sinus. The lesion may resemble a tuberculous skeletal infection, because the abscess is usually found in cancellous bone with little or no reactive sclerosis or periosteal response (Fig. 25.10). The location of

a lesion at a point of bony prominence—such as along the edges of the patella, the ends of the clavicles, or in the acromion, coracoid process, olecranon, or styloid process of the radius or ulna—may also suggest a fungal infection. Solitary marginal lesions of the ribs and lesions involving the vertebrae in an indiscriminate fashion, including the body, neural arch, and spinous and transverse processes, also favor fungal infectious process.

a lesion at a point of bony prominence—such as along the edges of the patella, the ends of the clavicles, or in the acromion, coracoid process, olecranon, or styloid process of the radius or ulna—may also suggest a fungal infection. Solitary marginal lesions of the ribs and lesions involving the vertebrae in an indiscriminate fashion, including the body, neural arch, and spinous and transverse processes, also favor fungal infectious process.

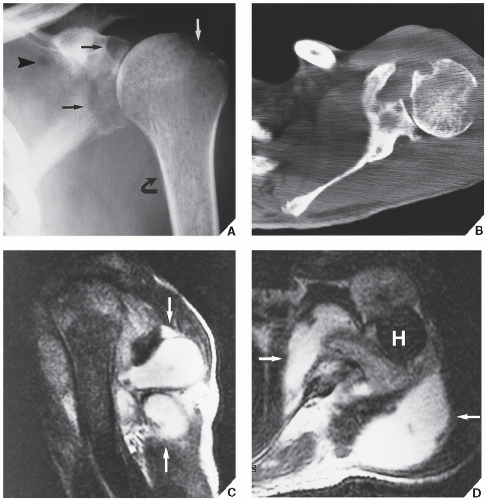

Among the fungal infections, coccidioidomycosis is of particular importance, not only because of an increase in the number of these infections in recent years but also because it may closely resemble skeletal tuberculosis. It is a systemic disease caused by the soil fungus Coccidioides immitis. This infection is endemic throughout the southwestern United States and the bordering regions of northern Mexico. Infection occurs through inhalation of dust containing the organism. The primary site of infection is the lung, and disease is commonly asymptomatic. Dissemination of coccidioidomycosis is rare, but the incidence is increased in patients with specific risk factors. Those at increased risk include African Americans, Filipinos, Mexicans, males, pregnant women, children younger than 5 years, adults older than 50 years, and immunosuppressed patients. Patients with disseminated coccidioidomycosis usually present during the course of primary pulmonary infection. However, some patients with disseminated disease may have no clinical history or radiographic evidence of pulmonary disease. The skin and subcutaneous tissues are the most common sites of disseminated coccidioidal infection, followed by mediastinal involvement. The skeletal system is the third most common site of dissemination, and osseous manifestations occur in 10% to 50% of patients with disseminated disease.

Radiographic presentation of the lesion of coccidioidomycosis is variable, but it is usually characterized by well-marginated, punched-out osteolytic lesions, typically involving long and flat bones. The lesions are typically unilocular but occasionally may be multiloculated. The other pattern frequently observed is a permeative type of bone destruction, only occasionally accompanied by periosteal reaction. Soft-tissue swelling and osteoporosis are much more common with the permeative pattern than with the punched-out lesions. The third most common pattern is joint involvement (septic arthritis), usually monoarticular and almost invariably associated with osseous involvement. Changes typically seen in joints include periarticular osteoporosis, a permeative/destructive pattern involving both articular surfaces, soft-tissue swelling, and occasional periostitis. Joint involvement in coccidioidomycosis is indistinguishable from that seen with tuberculosis. Involvement of the spine most commonly manifests as vertebral osteomyelitis or rarely as disk space infection (spondylodiskitis). In the former variant, both punched-out and permeative lesions are observed in the vertebral bodies. Cases with almost complete vertebral destruction have also been reported. Coccidioidomycosis often involves the vertebral appendages, and paraspinal soft-tissue extension is common. Disk space narrowing and gibbous deformity, although previously reported, are unusual findings in coccidioidomycosis, whereas both these findings are common in tuberculosis.

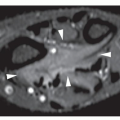

Scintigraphy is valuable in the evaluation of patients with disseminated coccidioidomycosis. Radionuclide scans using gallium-67 (67Ga) citrate and technetium-99m (99mTc) methylene diphosphonate (MDP) have been used to localize disease and can identify disseminated lesions that are clinically unsuspected. No false-negative bone scans have been reported. CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are helpful in defining bony involvement and in determining the extent of soft-tissue disease (Fig. 25.11). The lesions exhibit low attenuation, often appearing bubbly and expansive. On

MRI, the lesions show decreased signal on T1-weighted images, with a corresponding increase on T2-weighted and gradient-echo sequences.

MRI, the lesions show decreased signal on T1-weighted images, with a corresponding increase on T2-weighted and gradient-echo sequences.

Recently, osteomyelitis caused by Nocardia asteroids has been reported in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection who developed aquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). The clinical and imaging manifestations of this infectious process closely resemble those of tuberculosis. The most cases of Nocardia osteomyelitis resulted from direct extension of soft-tissue infection; however, hematogenous dissemination has also been reported.

Syphilitic Infection

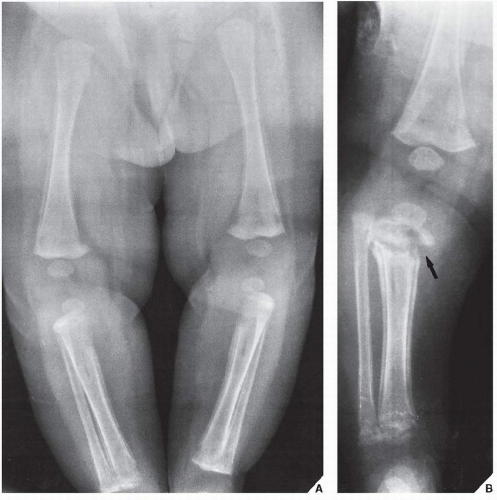

Syphilis is a chronic systemic infectious disease caused by a spirochete, Treponema pallidum. Congenital syphilis, which is transmitted from mother to fetus, may manifest as a chronic osteochondritis, periostitis, or osteitis. The lesions, which most frequently involve the tibia, are characteristically widespread and symmetric in appearance; destructive changes are usually seen in the metaphysis at the junction with the growth plate, producing what is called the Wimberger sign (Fig. 25.12). In the later stages of disease, involvement of the tibia results in a characteristic anterior bowing known as “saber-shin” deformity.

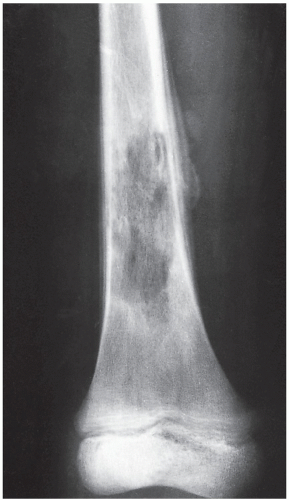

Acquired syphilis may manifest either as a chronic osteitis exhibiting irregular sclerosis of the medullary cavity or as syphilitic abscesses known as gumma (Fig. 25.13). The latter form of the disease may simulate pyogenic osteomyelitis, but the absence of sequestra typically found in bacterial osteomyelitis allows the distinction to be made.

Differential Diagnosis of Osteomyelitis

Usually, the radiographic appearance of osteomyelitis is so characteristic that the diagnosis is easily made with the clinical history, and ancillary radiologic examinations such as scintigraphy, CT, and MRI are rarely needed. Nevertheless, osteomyelitis may at times mimic other conditions. Particularly in its acute form, it may resemble Langerhans cell histiocytosis or Ewing sarcoma (Fig. 25.14). The soft-tissue changes in each of these conditions, however, are characteristic and different. In osteomyelitis, soft-tissue swelling is diffuse, with obliteration of the fascial planes, whereas Langerhans cell histiocytosis, as a rule, is not accompanied by significant soft-tissue swelling or a mass. The extension of a Ewing sarcoma into the soft tissues presents as a well-defined soft-tissue mass with preservation of the fascial planes. The duration of a patient’s symptoms also plays an important diagnostic role. It takes a tumor such as a Ewing sarcoma from 4 to 6 months to destroy the bone to the same extent that osteomyelitis does in 4 to 6 weeks and that Langerhans cell histiocytosis does in only 7 to 10 days. Despite these differentiating features, however, the radiographic pattern of bone destruction, periosteal reaction, and location in the bone may be very similar in all three conditions (see Fig. 22.10).

A bone abscess, particularly in the cortex, may closely simulate a nidus of osteoid osteoma (see Fig. 17.18). In the medullary region, however, the presence of a serpentine tract favors the diagnosis of bone abscess over osteoid osteoma (Fig. 25.15).

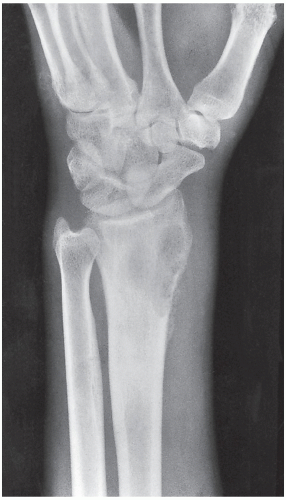

FIGURE 25.13 Acquired syphilis of bone. Oblique radiograph of the distal forearm of a 51-year-old man shows a lytic abscess (gumma) in the lateral aspect of the distal radius. |

FIGURE 25.15 Bone abscess resembling osteoid osteoma. A 17-year-old boy had a typical history of osteoid osteoma: nocturnal bone pain relieved promptly by salicylates. Anteroposterior radiograph of the distal forearm demonstrates a radiolucent lesion in the distal ulnar diaphysis. The presence of a serpentine tract extending from the radiolucent focus into the growth plate (arrow heads) indicates a diagnosis of bone abscess.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|