Ovarian and Pelvic Varices in the Female Patient

The etiologies of pelvic pain are numerous and are classified broadly as congenital or acquired. A partial listing includes infectious, neoplastic, vascular, neurologic, iatrogenic, and those related to organ systems such as the urogenital and gastrointestinal tracts. Vascular etiologies include arterial or venous causes (e.g., arteriovenous malformations, ovarian and pelvic varices). This chapter focuses on the management of pelvic pain secondary to venous abnormalities, specifically, the treatment of ovarian and pelvic varices as a cause of pelvic pain in women.

In the United Kingdom, pelvic pain is the most common reason for laparoscopy. No cause is found in 75% of cases.1 It has been estimated that 150,000 to 200,000 women in the United States have varicose veins in the pelvis. Unlike in men, in whom varicoceles may be associated with decreased fertility, this association has not been described in female patients with ovarian and pelvic varices. Although 15% of all women have ovarian and pelvic varices, only some of these women have accompanying pain.2–4

The presence of ovarian and pelvic varices may be associated with a group of symptoms referred to as pelvic pain syndrome or pelvic congestion syndrome.5 The authors believe these terms have outiived their usefulness and carry an unwanted psychiatric connotation. We propose that this condition be called pelvic venous incompetence (PVI), a more accurate and less pejorative descriptor.

Definition of Terms

Definition of Terms

In the context of this chapter, the term ovarian varices refers to varicosities seen after injecting contrast into the ovarian veins. The term pelvic varices will be defined as those visualized when injecting contrast into the internal iliac veins.

Approach to the Patient with Pelvic Pain

Approach to the Patient with Pelvic Pain

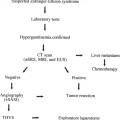

Recognizing that pelvic pain may be caused by numerous clinical entities, we have found that a multidisciplinary approach to the patient is helpful. At our institution, a pelvic pain clinic has been established, staffed by the following disciplines: gynecology, gastroenterology, physical therapy, regional anesthesia, interventional radiology, neurology, orthopedic surgery, general surgery, psychiatry, and social services. This team approach is particularly useful in selecting those patients most likely to benefit from embolization of ovarian and pelvic varices.

Clinical Features of the Patient with Ovarian and Pelvic Varices

Clinical Features of the Patient with Ovarian and Pelvic Varices

Women with symptomatic ovarian and pelvic varices sometimes complain of the following: (1) pain that is worse during the day and in the upright position, (2) “heaviness” or “pelvic fullness” associated with pain, and (3) pain with intercourse. The pain level may worsen in the postpartum interval. Ovarian and pelvic varices may occur concurrently with varices in the legs and vaginovulvar region.

Imaging

Imaging

In the female patient with chronic pelvic pain and a negative laparoscopy, pelvic varices must be considered a possible source of pain. The degree of pelvic venous engorgement may be underestimated, particularly in the supine position used during cross-sectional imaging or in the Trendelenburg position during laparoscopy.6 Because most patients with PVI are of reproductive age, radiologic evaluation using ionizing radiation must be kept to a minimum.7 The mean age in one series of 35 patients with PVI was 32.4 years.8

Several imaging modalities have been used to evaluate women with suspected ovarian and pelvic varices, including the following: (1) ultrasonography (performed either transabdominally or transvaginally); (2) vulvar phlebography (i.e., the injection of contrast media into vulvar varices after surgical exposure of a vein or percutaneous venous puncture); (3) transuterine venography (an outpatient procedure in which the patient is placed in a lithotomy position and a specially designed cannula with a needle is placed through the cervix into the myometrium; hyaluronidase and iodinated contrast material then are injected, and pelvic films are obtained over time, usually at 20 to 40 seconds after injection); and (4) selective ovarian and internal iliac venography. The techniques of transuterine venography, as described by Beard et al9 and Murray and Comparato,10 and selective ovarian and internal iliac venography have been associated with few complications.

In an article describing the radiology of ovarian varices by Kennedy and Hemmingway,7 the authors stated that patients who have undergone both transuterine and selective ovarian venography find the latter to be “far less distressing and virtually pain free” compared with the former. In this chapter, the technique of selective catheterization of the ovarian and internal iliac veins will be emphasized.

When possible, it is recommended that ultrasound imaging of the patient with suspected ovarian and pelvic varices be performed with the patient in the supine and erect positions. It may not be possible to obtain upright pelvic ultrasound studies easily, and patients with PVI may have normal upright ultrasound scans.7 Thus, a normal ultrasound scan does not rule out ovarian and pelvic varices. The purpose of cross-sectional imaging, then, is to rule out other pathological conditions, such as tumors and uterine leiomyomata.

Other ovarian pathology characterized by ultrasound, performed either transabdominally or transvaginally, include polycystic ovaries, solid masses, and vascular structures. Doppler studies can confirm that vessels identified are dilated veins and show nonpulsatile flow. Frequently, the audible signal is better than the visual Doppler display because the sluggish flow within the larger vessels. The iliac and uterine arteries typically show pulsatile Doppler signal.7 If the clinical suspicion for ovarian and pelvic varices is high, and imaging studies are negative, then diagnostic venography “with the intention to treat varices” is (at our institution) the next step.

Pitfalls of the Physical Examination and Cross-sectional Imaging

Not infrequently, a woman with chronic pelvic pain of indeterminate etiology undergoes a physical examination and cross-sectional imaging. The latter may include a transabdominal or endovaginal ultrasound, a computed tomography (CT) scan, or a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. Because such procedures are performed with the patient in the supine position, ovarian and pelvic varices may be overlooked. In such instances, distention of venous structures generally is limited by reduced intravascular pressure and resultant venous decompression when the patient is supine. In men, the situation is clinically similar. A varicocele, the analogous male condition, may not be detectable if the patient is examined in the supine position. Only in the upright position do the scrotal varicosities become clinically evident and generally palpable. The similar venous anatomy of ovarian and pelvic varices compared with the male varicocele lends credence to the notion that the former may be missed entirely using conventional supine cross-sectional imaging.

It might seem that direct endoscopic visualization of pelvic anatomy through laparoscopy would reduce the incidence of false-negative evaluations. At pelvic laparoscopy, however, the patient is frequently placed in a Trendelenberg position (i.e., body inclined with head down) and the peritoneal cavity is insufflated with carbon dioxide. Such maneuvers may optimize endoscopic visualization, but they have the added effect of ovarian and iliac venous decompression.

Etiology and Clinical Research

Etiology and Clinical Research

Lechter and Alvarez11 and Hobbs12 each concluded that the primary problem in the female varicocele is retrograde flow in incompetent ovarian veins. These investigators successfully treated a small series of patients by ligation of the ovarian veins.

A case report by Edwards et al6 described successful treatment of a patient with PVI by bilateral ovarian vein embolization using transcatheter embolotherapy. A 40-year-old woman with a 2-year history of chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, and dysmenorrhea remained asymptomatic after embolotherapy at 6 months’ follow-up. After treatment, her menstrual cycle became regular, and she no longer complained of dysmenorrhea. Follow-up venography 1 month after transcatheter embolotherapy demonstrated complete occlusion of both ovarian veins. Internal iliac venography showed no evidence of reflux into the ovarian venous plexus.6

Sichlau et al13 reported percutaneous transcatheter embolization of the ovarian veins (with steel occlusion coils) in three women with chronic pelvic pain and demonstrated ovarian varices. Initially, pelvic pain was relieved in all three patients and lasted more than 2 years in two of the three patients. One patient had a symptom recurrence at 1.2 years and eventually required surgery (i.e., total hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy).

Tarazov et al14

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree