Key Facts

Paget’s Disease

- •

The cause of Paget’s disease is not known.

- •

Patients are frequently asymptomatic.

- •

It is often an incidental finding on imaging studies.

- •

It is usually seen after the fourth decade.

- •

The pelvis, femora, tibia, vertebra, and sacrum are favored locations.

- •

Three phases are distinguishable: lytic, intermediate, and sclerotic.

- •

Involvement may be monostotic or polyostotic and asymmetric.

- •

The “blade of grass” appearance and involvement that include the end of a bone usually allow the lytic phase of Paget’s disease to be correctly identified on radiographs.

- •

Thickened cortices and trabeculae are typical features.

- •

Preservation of normal marrow fat is a characteristic finding of the lytic phase of Paget’s disease on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and allows it to be distinguished from most tumors.

- •

Paget’s bone may not be hypermetabolic on positron emission tomography scanning (unlike many tumors).

- •

Complications of Paget’s disease include fractures (incomplete or complete), benign or malignant tumors, and degenerative arthritis.

- •

MRI is usually reliable in separating secondary sarcoma from uncomplicated Paget’s disease.

Fibrous Dysplasia

- •

Designated a neoplasm in the World Health Organization classification

- •

All ages affected; there is no racial/ethnic predilection.

- •

Monostotic lesions are more common than polyostotic.

- •

Most common benign lesion of a rib.

- •

McCune Albright syndrome (polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, café-au-lait spots and hyperfunctioning endocrinopathies).

- •

Mazabraud’s syndrome consists of a soft-tissue myxoma and fibrous dysplasia.

- •

Malignancy is very rare.

- •

Low-grade central osteosarcoma is often misdiagnosed as fibrous dysplasia.

Sarcoidosis

- •

More common in blacks.

- •

Nonspecific synovitis; ankle synovitis should suggest the diagnosis.

- •

Bone lesions, lytic or sclerotic; lacy pattern in the phalanges.

- •

MRI demonstrates marrow lesions.

- •

Vertebral destruction is rare.

PAGET’S DISEASE

Paget’s bone disease has been present for at least a thousand years. Human remains found in Lancashire, England dated to about 900 C.E. clearly show the characteristic osseous changes that are now recognized as Paget’s disease. The disorder is named for Sir James Paget who, in 1877, provided a description so perceptive that it holds true today: “It begins in middle age or later, is very slow in progress—no other trouble than those which are due to change of shape, size and direction of the diseased bones.”

Etiology

The cause of Paget’s disease remains unknown. Of the proposed causes, a viral etiology has some support.

The cause of Paget’s disease is uncertain but likely involves genetic and environmental factors; a virus may play a role.

Clinical Features

Paget’s disease is common in Western society and is found in about 1% of the U.S. population over 40 years of age. It appears that there has been a decline in the prevalence and severity of the disorder in recent years. It usually affects individuals over the age of 40 years. The disease appears to be uncommon in China, the Indian subcontinent, and Africa. Most patients with Paget’s disease are asymptomatic, and the disease is most frequently encountered as incidental findings on imaging studies.

Unlike other metabolic disorders, Paget’s disease is unusual in that it may be monostotic or polyostotic and asymmetric.

Imaging

Virtually any bone can be affected by Paget’s disease. It predominates in the pelvis, sacrum, lumbar segment of the vertebral column, calvarium, and long bones with a preference for the ends of long bones ( Figures 29-1 through 29-3 ).

Except in the tibia, Paget’s disease always involves the end of a bone.

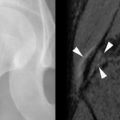

The disease has three distinct phases: lytic, intermediate, and sclerotic ( Figure 29-4 ). Exacerbation of the lytic phase may be encountered after the intermediate and sclerotic phases have set in. The purely lytic phase of the disease is the rarest manifestation, and only 1% to 2% of patients with Paget’s disease clinically exhibit a purely lytic stage of involvement ( Figure 29-5 ). Because of the aggressive radiographic appearance of the lytic phase of Paget’s disease, its relative rarity as the sole imaging finding, and the advanced age of the typical patient, the lytic phase is often confused with malignant disorders such as metastasis or lymphoma. A clue to the diagnosis of lytic Paget’s disease on the radiograph of long bones is the involvement of the end of the bone and the “blade of grass” appearance in which the advancing edge of the lesion has a sharply defined, tapered contour ( Table 29-1 ).

Technetium bone scintigraphy demonstrates a marked increase in radio-tracer accumulation. Although the marked uptake is consistent with a malignant disease process, the distribution of uptake often allows the correct diagnosis to be made. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), however, may permit more accurate characterization than the radiograph and suggest the correct diagnosis.

Lytic Paget’s disease may be differentiated from other disorders by MRI; there is preservation of fatty marrow in lytic Paget’s disease but replacement of marrow fat by tumor.

In purely lytic Paget’s disease, fatty marrow signal is preserved on MRI even in the presence of a radiographic lytic lesion ( Figure 29-5 ). This finding of fatty marrow preservation in osteolytic Paget’s disease is entirely in keeping with the histologic appearance of resorbed bone. The destruction of bone is caused by resorption, not infiltration; hence the preservation of marrow fat signal on MRI. Because of its aggressive nature and the need to exclude a more ominous disease, MRI ought to be performed when there is difficulty in distinguishing the “osteoporosis” of resorptive changes from the infiltration of a malignant disease process on radiographs ( Figure 29-6 ). Although a bone biopsy would resolve the issue, the procedure should be avoided because of the risk of fracture.

Bone biopsy should be avoided if possible in lytic Paget’s disease due to the risk of fracture.

An important variation in the location of lytic Paget’s disease to be borne in mind is that although an exclusively diaphyseal location is exceptional, it may be observed in the tibia ( Figures 29-7 and 29-8 ).

Intermediate and Sclerotic Phases

The intermediate phase is characterized by sclerosis, lysis, and thickened trabecula and cortices; it is the stage most frequently encountered radiographically and does not usually present a diagnostic problem ( Figures 29-1 through 29-3 ). The sclerotic phase of Paget’s disease is an advanced, late intermediate phase. As a consequence of the reparative process, an involved vertebra may become diffusely sclerotic—the so-called “ivory vertebra” ( Figure 29-9 ). If the vertebra is enlarged and dense, the diagnosis of Paget’s disease should be suggested.

The differential diagnosis of a dense vertebra includes metastasis and lymphoma. If the vertebra is enlarged, Paget’s disease should be favored.

Often a dense vertebra from Paget’s disease is not expanded and has to be distinguished from a sclerotic metastasis (usually from prostate or breast cancer). In this situation, the signal characteristics of MRI may not be helpful since the signal may be low on all pulse sequences due to the sclerosis. The presence of a soft tissue mass would favor a malignant etiology.

Complications of Paget’s Disease

Musculoskeletal complications of Paget’s disease include fractures, degenerative arthritis, and benign or malignant neoplasms.

Fractures

Fractures may be insufficiency fractures or complete fractures. Cortical insufficiency fractures, particularly in the femur and tibia, are more common than complete fractures. Insufficiency fractures may appear as single or multiple horizontal radiolucent lines favoring the convex aspects of bone, which distinguishes them from osteomalacic Looser zones that favor the concave aspects of long bones.

Insufficiency fractures in long bones involved by Paget’s disease involve the convex side of the bone.

Complete fractures are typically transverse and usually noncomminuted. They may occur spontaneously or follow minor trauma. These fractures may be seen in vertebrae and long bones with the subtrochanteric femur being the most common location.

Fractures occurring as a result of Paget’s disease are typically transverse, whereas traumatic fractures have varied configurations.

Neoplasms

Although uncommon, the most dreaded and serious complication of Paget’s disease is sarcomatous degeneration. The prevailing view is that sarcomatous degeneration affects about 1% of patients with Paget’s disease. MRI usually permits the differentiation of sarcomatous degeneration from uncomplicated Paget’s disease or the intermediate phase of Paget’s disease exacerbated by the lytic phase ( Figure 29-10 ). In addition, MRI is useful for tumor staging. Metastatic disease, myeloma, and lymphoma may also be superimposed on pre-existing Paget’s disease.

A rare benign tumor associated with Paget’s disease is a giant cell tumor. Interestingly, this tumor has been found to have a familial pattern and geographic cluster in Italian Americans whose ancestral roots were in a small town called Avellino. These tumors have been known to decrease in size after treatment with corticosteroids.

Giant cell tumors in Paget’s disease have been treated with corticosteroids.

Pseudosarcomas in Paget’s Disease

Periosteal proliferation from Pagetic bone can produce a soft tissue mass that clinically mimics a sarcoma. MRI effectively demonstrates these changes and marrow signal is usually preserved, distinguishing it from a sarcoma.

Rapid Osteolysis

This phenomenon may be observed in patients with an immobilized Paget’s fracture. Because sarcomas in Paget’s disease are often lytic, the development of osteolysis is a cause for concern ( Figure 29-11 ). Although we are not aware of MRI having been performed in this setting, we believe that the MRI findings will be those of osteoporosis. Thus, in a patient with an immobilized fracture through Paget’s bone, the lack of marrow infiltration especially on the T1-weighted sequences, could preclude the need for a biopsy.

Diffuse osteolysis may be observed in Paget’s bone in patients whose fractures have been immobilized.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree