Anatomy

7.1.1 Position

The pancreas is a secondarily retroperitoneal, intra-abdominal gland that is covered anteriorly by peritoneum. 1 The abdominal aorta and inferior vena cava run posterior to the pancreas. The pancreas is directed transversely with its right extremity, the head, nestled in the C-loop of the duodenum. It borders anteriorly on the posterior gastric wall and extends to the left toward the spleen. It forms the posterior boundary of the omental bursa, an intra-abdominal space that communicates with the rest of the abdominal cavity through a small lateral passage, the omental foramen.

The pancreas is approximately 15 cm long, 5 cm wide, and 2 to 3 cm thick and weighs 80 to 120 g. 2 It is a yellowish, lobulated gland whose exocrine tissues produce the pancreatic enzymes (including amylase and lipase) and whose endocrine tissues secrete the hormones insulin and glucagon, which are important in glucose metabolism. 2

The pancreas is divided into three main parts:

Head: The head of the pancreas rests within the curve of the duodenum and borders on the right side of the superior mesenteric artery and vein. The part of the pancreatic head that is posterior to the two mesenteric vessels is called the uncinate process. A short segment of the common bile duct passes through the pancreatic head. Normally it joins with the pancreatic duct and opens into the duodenum at the major duodenal papilla (of Vater).

Body: The body of the pancreas borders the pancreatic head and is formed by the portions that are anterior to the mesenteric vessels.

Tail: The pancreatic tail is located to the left of the portal vein and closely approaches the spleen.

Histology

The acinus is the smallest unit of the pancreas. This terminal glandular element is connected to a side branch, or ductule, into which it secretes its enzymes. Multiple acini combine to form a lobule, hence the description of the pancreas as a “lobulated organ.” This lobulation is variable in degree and may be lost as a result of disease.

7.1.2 Blood Supply

The pancreas receives its blood supply from branches of the celiac trunk and the superior mesenteric artery:

Celiac trunk:

The celiac trunk gives rise to the common hepatic artery, from which arises the gastroduodenal artery. The latter vessel, in turn, carries blood to the superior pancreaticoduodenal artery (anterior and posterior branches), which supplies the pancreatic head. 2

The celiac trunk also gives rise to the splenic artery, which gives off branches that supply the tail of the pancreas—the greater pancreatic artery, the artery to the pancreatic tail, and the dorsal pancreatic artery. 2

Superior mesenteric artery: The head of the pancreas is additionally supplied by the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery, which arises from the superior mesenteric artery. 1

The pancreatic head is circled by a vascular anastomosis formed by the superior pancreaticoduodenal artery (from the common hepatic artery) and posterior branches of the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery (from the superior mesenteric artery). 2

The pancreatic head is drained by the pancreaticoduodenal veins, which empty into the superior mesenteric vein or open directly into the portal vein. The pancreatic veins drain from the body and tail of the pancreatic into the splenic vein (see ▶ Fig. 7.1). 1

Fig. 7.1 Blood supply of the pancreas and duodenum. Anterior view. (a) Arterial supply. (b) Venous drainage.

(Reproduced from Schünke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. Prometheus. LernAtlas der Anatomie: Innere Organe. Illustrated by M. Voll/K. Wesker. 2nd ed. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2009.)

7.1.3 Development

The pancreas develops from one ventral bud and one dorsal bud, which fuse during embryonic development to form one organ (▶ Fig. 7.2). 1 Each of the buds has one duct, and he two ducts normally unite during development to form the main pancreatic duct. 1 Failure of the two ducts to unite may result in two ducts running the length of the pancreas. With incomplete union of the ducts in the pancreatic head, a remnant of the duct of the dorsal bud may remain as the accessory pancreatic duct (of Santorini).

Fig. 7.2 Embryonic development of the pancreas. (a) Dorsal and ventral pancreatic buds. (b) Fusion of the two buds. (c) Failure of fusion of the two ducts of the dorsal and ventral buds. (d) Incomplete fusion of the dorsal and ventral ducts.

(Reproduced from Schünke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. Prometheus. LernAtlas der Anatomie: Innere Organe. Illustrated by M. Voll/K. Wesker. 2nd ed. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2009.)

Exocrine secretions are channeled by the side branches into the pancreatic duct (of Wirsung) and are discharged into the duodenum through the major duodenal papilla (of Vater). The normal diameter of the pancreatic duct is 3 to 5 mm. If an accessory pancreatic duct is present, it may have its own papilla, the minor duodenal papilla, which opens into the duodenum at a more proximal level than the greater duodenal papilla. 2 As a variant, the pancreatic duct may fail to fuse with the common bile duct, so that the latter opens into the duodenum through a separate papilla. Thus, there may be up to three papillae.

Note

The diameter of the pancreatic duct is less than 5 mm.

7.1.4 Imaging Landmarks

Landmarks in CT and MRI

The superior mesenteric artery and vein run at right angles to the pancreas.

The splenic vein runs along the pancreatic tail from the spleen toward its confluence with the superior mesenteric vein; their union forms the hepatic portal vein. Viewed in coronal section, the splenic vein runs a slightly oblique course and usually descends slightly from the splenic hilum to the splenic–mesenteric confluence.

The head of the pancreas is situated within the duodenal C loop. The uncinate process of the pancreatic head is posterior to the superior mesenteric vein and artery. The “hydro CT” technique (administering IV hyoscine butylbromide to immobilize the bowel, giving 0.5 to 1.5 L of water orally within 30 minutes of imaging, and positioning the patient in 45° left lateral decubitus) 3 can be used to improve contrast between the pancreatic head and surrounding bowel.

The pancreatic tail is located to the left of the portal vein.

Sonographic Landmarks

Blood vessels are useful landmarks for ultrasound scanning of the pancreas. Orientation can be established by locating the portal vein at the porta hepatis and tracing the vein upward to the portal vein junction, around which lies the pancreatic head.

Another localizing technique is to image the inferior vena cava and aorta in a transverse scan and follow them to the mesenteric vessels, which are bordered anteriorly by the body of the pancreas.

The splenic vein is posterior to the pancreas (▶ Fig. 7.1) and provides a landmark for imaging the pancreatic tail.

Note

Because the pancreatic tail is angled slightly upward relative to the pancreatic head, the ultrasound probe should be angled somewhat when positioned below the left costal arch and should be aimed slightly cephalad relative to the left side of the patient.

Selection of Imaging Modalities The initial imaging study in most patients with clinical suspicion of pancreatic disease is upper abdominal ultrasound, as it is widely available and can provide an effective survey centered on the pancreas. Ultrasound can establish a pancreatic cause for the patient’s complaints when correlated with other findings. If the cause is still unclear, further investigation by CT or MRI is definitely indicated to exclude a malignant process or detect complications. The preferred imaging modality is decided on an individual basis according to availability and the patient’s clinical status. The appropriate application of a given technique for specific entities is described in the sections below. Note that patient-specific parameters such as pain and contraindications to CT or MRI may require some deviation from the gold standard.

7.1.5 Normal Variants and Congenital Anomalies

Pancreas divisum

Brief definition Pancreas divisum is one of the most common congenital malformations of the pancreas. 4 It may be complete or incomplete and results from absent or incomplete fusion of the dorsal and ventral pancreatic buds during embryonic development. 5 Each of the buds has its own duct, and the two ducts normally fuse and drain into the duodenum at the major papilla. In the complete form of pancreas divisum, the ducts fail to unite due to absent or incomplete fusion of the buds, with the result that the pancreatic duct has a separate opening at the minor duodenal papilla (▶ Fig. 7.3a). 5 Secretions from the larger dorsal bud (pancreatic duct) drain through the lesser papilla while the smaller ventral bud drains through an accessory pancreatic duct to the major papilla. 5 With incomplete pancreas divisum, the main pancreatic duct and accessory duct are interconnected by a small channel (▶ Fig. 7.3b, ▶ Fig. 7.4).

Fig. 7.3 Pancreas divisum. Schematic representation. (a) Incomplete pancreas divisum. (b) Complete pancreas divisum.

(Reproduced from Schünke M, Schulte E, Schumacher U. Prometheus. LernAtlas der Anatomie: Innere Organe. Illustrated by M. Voll/K. Wesker. 2nd ed. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2009.)

Fig. 7.4 Incomplete pancreas divisum. MRCP. (a) The pancreatic ducts open separately into the duodenum. (b) The pancreatic ducts are interconnected by a small channel (arrow).

Imaging signs Besides the main pancreatic duct, an additional duct is found within the parenchyma of the pancreatic head when pancreas divisum is present. In the complete form of the anomaly, the main pancreatic duct opens at the minor papilla as described above while the accessory pancreatic duct opens jointly with the common bile duct at the major papilla. MRCP is the imaging study of first choice, as it is superior to CT for ductal imaging (see Chapter ▶ 6.3.4). A relatively narrow accessory pancreatic duct leads to a rise of intraductal pressure. 6 There is disagreement whether the elevated pressure predisposes to chronic pancreatitis.

Annular Pancreas

Brief definition Annular pancreas is an embryonic malformation of the pancreas that occurs during the fourth week of gestation. 7 It is the second most common congenital anomaly of the pancreas, with a prevalence of 0.05%. 7 Like pancreas divisum, it involves a developmental abnormality of the two pancreatic buds. The ventral bud consists of right and left parts; the left part generally regresses, while the right part migrates around the back of the duodenum and fuses with the dorsal bud. 1 If the left part does not regress but migrates around the front of the duodenum and fuses with the right part, a ring of pancreatic tissue is formed around the C loop of the duodenum (▶ Fig. 7.5). This ring may cause constriction of the duodenum in adults. 1

Fig. 7.5 Annular pancreas. Incomplete fusion of the dorsal and ventral pancreatic buds (fourth week of gestation). Pancreatic tissue encircles the duodenum (arrows). (a) Axial CT. (b) Coronal CT.

Imaging signs CT displays the duodenum surrounded by a continuous ring of uniformly enhancing pancreatic tissue. This tissue is continuous with the pancreatic body and forms the ring from which the condition derives its name (see ▶ Fig. 7.5a). On MRI the tissue is isointense to pancreas in all sequences and encircles the descending part of the duodenum as described above.

Pitfalls An inexperienced examiner may misinterpret the ring of the pancreatic tissue around the duodenum as a complex “cyst” located at the center of the pancreatic head (see ▶ Fig. 7.5a).

7.2 Nonneoplastic Diseases

7.2.1 Acute Pancreatitis

Brief definition Acute pancreatitis is an acute inflammation of the pancreas that runs a mild, self-limiting course in the great majority of cases. In approximately 20% of cases, however, the disease takes a severe course that leads to various complications as well as life-threatening conditions and permanent organ dysfunction. 8 The pathophysiology is believed to involve an uncontrolled activation of the enzyme trypsin in the acinar cells, leading to autodigestion of the pancreas with resulting inflammation and necrosis. 8 A cause cannot be identified in 15 to 20% of adult patients, who are said to have “idiopathic pancreatitis.” 8 An etiology can be established in the remaining 80 to 85% and most commonly involves a biliary cause. The second most frequent cause is alcohol abuse, followed by drug toxicity (corticosteroids, diuretics, etc.), trauma, iatrogenic causes (post-ERCP), infection (mumps, cytomegalovirus, coxsackievirus, etc.), and elevated serum calcium levels as in primary hyperparathyroidism. 8 Acute pancreatitis may lead to many pathologic changes in the organ itself and in regional tissues. 9

Caution

Pancreatic necrosis is one of the most serious complications involving the pancreas and should be diagnosed or excluded as early as possible. 8

Besides complications involving the organ itself, various types of intra-abdominal fluid collections and fat necrosis may occur. 9 Several scoring systems have been developed for assessing severity, including the APACHE II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation), SOFA (Sequential Organ Failure Assessment), and Ranson scores. 10, 11, 12, 13 They all employ a point system for scoring various organ systems. The higher the total score, the more complicated the course. 10 Organs that are affected and scored include the kidney, central nervous system, cardiovascular system, respiratory tract, and hematologic system. Most complications are diagnosed from the clinical examination and laboratory tests.

Special form: paraduodenal pancreatitis Paraduodenal pancreatitis, also called groove pancreatitis, is a type of focal pancreatitis in which the inflammatory process affects the groove between the pancreatic head, the duodenum, and the common bile duct (▶ Fig. 7.6a). If scarring occurs in that area, sectional images may show apparent thickening of the duodenal wall at the level of the papilla or a tumorlike lesion of the pancreatic head, leading to errors in diagnosis. 5 Paraduodenal pancreatitis may also occur in association with a duodenal tumor: The thickened duodenal wall obstructs the papilla and blocks the drainage of biliary and pancreatic secretions, resulting in autolysis of the pancreas.

Fig. 7.6 Acute pancreatitis. CT. (a) Paraduodenal pancreatitis. Axial CT shows a faintly enhancing fluid collection between the pancreatic head and thickened duodenal wall (arrows) with a typical intramural cyst (arrowhead). (b) Edematous interstitial pancreatitis. Enlargement of the pancreas (arrows) and peripancreatic exudates (arrowheads) are typical findings. (c) Encapsulated colliquative necrosis (arrows) in necrotizing pancreatitis with fat inclusions (arrowheads) and loss of the normal lobulated structure.

Note

The findings of paraduodenal pancreatitis include edematous swelling of the pancreatic head and typical fluid collections in the groove between the pancreatic head and the duodenum. The inflammation usually spares the rest of the pancreas. Whenever imaging reveals the typical fluid track, paraduodenal pancreatitis should be suspected and the duodenum evaluated further by endoscopy and biopsy to exclude a malignant process.

Imaging signs The main role of imaging in acute pancreatitis is follow-up and the (prompt) detection of complications. Pancreatitis can be diagnosed from clinical and laboratory findings. Transabdominal ultrasound can be added when scanning conditions are good and will show a hypoechoic, edematous pancreas with fluid collections and possible cholestasis (▶ Fig. 7.7). CT and MRI are unnecessary for making a diagnosis. Both modalities are used if complications arise.

Fig. 7.7 Acute pancreatitis. Ultrasound in acute pancreatitis shows edematous swelling of the pancreatic head and body–tail junction (large arrows) with fluid tracking around the pancreatic head (small arrow).

Caution

The radiological exclusion of pancreatic necrosis should be delayed at least 72 hours after onset of symptoms to avoid false-negative results, as some time is needed for the visible demarcation of necrosis. MRI and CT are equivalent in their ability to detect necrosis, but contrast-enhanced CT is preferred from the standpoint of examination time and patient tolerance, as patients with acute pancreatitis are seriously ill and a shorter scan time may be beneficial.

CT demonstrates fluid collections around the pancreas (▶ Fig. 7.6b). Necrosis appears as an ill-defined hypodense area in the pancreas with loss of normal lobular architecture and loss of definition of normal organ boundaries (▶ Fig. 7.6c). Infection of the necrotic area by ascending intestinal organisms leads to abscess formation, with such typical imaging as air inclusions and an enhancing abscess wall. Intra- and/or extrahepatic cholestasis may be noted, depending on location and etiology. Portal vein thrombosis with ascites may develop. Pleural effusion and other pulmonary complications such as infiltrates may also be found. A unilateral pleural effusion (usually on the left side) in pancreatitis is called a “sympathetic” pleural effusion. Opacity of both lungs is suspicious for ARDS as a complication of pancreatitis. Some patients develop a reactive paralytic ileus in response to retroperitoneal irritation, characterized by distended bowel loops and air–fluid levels. Coagulation defects in a setting of severe acute pancreatitis may lead to spontaneous intra-abdominal hemorrhage, and CT may show diffuse stranding of the intra-abdominal fat. CT is also used to direct the percutaneous drainage of necrotic areas and abscesses.

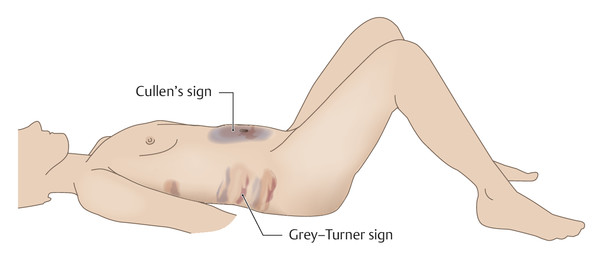

Clinical features The main clinical findings are acute upper abdominal pain combined with at least a 3-fold elevation of amylase and lipase activity and increased C-reactive protein activity. The upper abdominal pain may be a girdling pain that radiates to the back. Nausea and vomiting may also be present. 14 Other possible symptoms are jaundice due to obstruction of the common bile duct, ascites, and pleural effusion, which indicate a severe course. On physical examination, the Grey–Turner sign may be noted in the flank region and Cullen’s sign around the umbilicus. 8 Bruising in the flank and periumbilical regions is considered pathognomonic for severe acute pancreatitis (▶ Fig. 7.8). It occurs when the autodigestive process spreads from sites of pancreatic necrosis into adjacent abdominal compartments and causes disruption of cutaneous vessels with formation of hematoma. 8 The central question to be addressed in acute pancreatitis is whether it is a mild or severe form:

Mild form: In the Atlanta Classification, the mild form of acute pancreatitis is associated with minimal organ dysfunction and a self-limiting course. It requires fluid replacement along with antiemetic and analgesic therapy. 15

Severe form: Severe cases require patient surveillance in ICU due to the potential for systemic complications with sepsis, hypovolemic shock, and multisystem organ failure. 15

Fig. 7.8 Cullen’s sign and Grey–Turner sign.

The Atlanta Classification of acute pancreatitis has been revised since its inception. In addition to mild and severe forms, the latest revision distinguishes between an early phase (within the first week of onset) and a late phase (after the first week of onset). 16 In the early phase of acute pancreatitis, a severe form is defined as organ failure of more than 48 hours’ duration; in the late phase it is defined as permanent organ failure, death, or complications. 16 In the revised Atlanta Classification, the Marshall score is used to evaluate organ failure based on scores for the respiratory, cardiovascular, and renal systems. 16

Note

A daily clinical examination that includes the above scores is important, as it is the only way to ensure the prompt detection of complications and the institution of appropriate treatment and surveillance.

Serum amylase and serum lipase are the two pancreatic enzymes that are determined in patients with acute pancreatitis. At least a 3-fold increase in amylase activity combined with increased lipase activity support the diagnosis when correlated with clinical findings. The enzyme activities remain elevated for approximately 3 to 5 days. 8 Enzyme elevation in the absence of clinical findings, or the presence of atypical clinical findings, is insufficient for a diagnosis of pancreatitis, and a differential diagnosis is required. Pancreatic enzymes are not useful parameters for follow-up.

Differential diagnosis

Acute exacerbation of chronic pancreatitis.

A malignant process in the pancreatic head or adjacent duodenum that has caused pancreatitis due to compression of the common bile duct.

Pitfalls The premature use of CT to exclude necrosis may yield false-negative findings. On the whole, sectional imaging should be used sparingly in acute pancreatitis because mild cases do not require it.

Key points In 80% of cases acute pancreatitis is a mild, self-limiting disease that does not require sectional imaging. In the 20% of patients with severe disease, sectional imaging should be used for the exclusion of necrosis and other complications. It should not be scheduled earlier than 72 hours after symptom onset.

7.2.2 Chronic Pancreatitis

Brief definition Chronic pancreatitis is a chronic inflammation of the pancreas that leads to fibrotic changes in the organ and destruction of the duct system with consequent long-term exocrine and endocrine pancreatic insufficiency. 17 The disease leads to functional and morphological organ damage. Chronic pancreatitis has a worldwide incidence of 1.6 to 2.3/100,000 population per year, with a rising prevalence. 18 The leading cause of chronic pancreatitis in adults is alcohol abuse, which underlies 50 to 84% of cases. 17, 19 Daily alcohol consumption of 80 g or more for a period of 6 to 12 years is considered a risk factor for the development of chronic pancreatitis. 20 Idiopathic chronic pancreatitis ranks second, accounting for 28% of cases. 17 Approximately 45% of these cases are referable to genetic factors. 17 Researchers have identified several gene mutations that predispose to chronic pancreatitis, such as the cationic trypsinogen gene (PRSSI). Mutations of this gene lead to chronic pancreatitis with a penetrance of up to 80%. 21 Another, less common cause is hyperparathyroidism. Pancreas divisum is suspected of increasing the risk of chronic pancreatitis, but this link has not been proven. 17 Besides long-term exocrine and endocrine pancreatic insufficiency, other typical complications have been identified: Pseudocyst formation may be clinically silent or may lead to infection and intralesional hemorrhage. Moreover, the infection of necrotic tissue may have severe and potentially fatal consequences. Pseudoaneurysms of the splenic artery or superior mesenteric artery may form in the chronically inflamed pancreas. There may also be biliary tract obstruction with impaired biliary drainage, pyloric and duodenal stenosis, and fistulation to the skin, adjacent hollow organs, or the (retro)peritoneum (▶ Fig. 7.9). Imaging cannot always positively distinguish between inflammation and neoplasia, and equivocal findings always require histological investigation. Patients with chronic pancreatitis are at increased risk for developing pancreatic cancer. 22

Fig. 7.9 Superior mesenteric artery pseudoaneurysm in pancreatitis. CT. (a) Scan in the arterial phase shows a small pseudoaneurysm of the superior mesenteric artery (arrow) following a pylorus-preserving pancreatic head resection. (b) Scan in the venous phase 3 weeks later shows marked enlargement of the pseudoaneurysm (arrow).

Note

Chronic pancreatitis is a chronic inflammation of the pancreas leading to fibrotic organ changes and duct destruction with consequent long-term exocrine and endocrine insufficiency. The leading cause is alcohol abuse. Complications include pseudocysts, necrosis, pseudoaneurysms, strictures, fistulas, and malignant transformation.

Imaging signs Imaging in chronic pancreatitis is the third diagnostic pillar along with clinical examination and function tests. Imaging is also used for follow-up, for the investigation of complications, and if necessary to direct preoperative planning. The initial imaging study of choice is transabdominal ultrasound (▶ Fig. 7.10). This is useful for initial diagnosis and for detecting complications such as pseudocysts (echo-free with posterior acoustic enhancement) and biliary tract obstruction with cholestasis (diameter of the common bile duct up to 7 mm in patients with a gallbladder, up to 10 mm after cholecystectomy). Other imaging modalities are contrast-enhanced ultrasound for detection of necrosis (preferred over CT with iodinated contrast in patients with impaired renal function) 17; endoscopic ultrasound, which can detect early parenchymal changes owing to its higher spatial resolution 17; and CT and MRI, which have an adjunctive role. CT and MRI are particularly useful for differentiating chronic pancreatitis from tumor, the follow-up of complications, and preoperative planning. Sectional imaging can also be important in determining etiology, as it can detect congenital anomalies such as pancreas divisum as well as autoimmune pancreatitis. Signs of chronic pancreatitis are parenchymal calcifications (▶ Fig. 7.11), parenchymal atrophy, and, in an acute flare, edematous enlargement of the pancreas with peripancreatic fluid collections. Pseudocysts are sharply circumscribed lesions of fluid density or fluid signal intensity that do not communicate with the duct system and usually originate from necrotic areas. Pseudoaneurysms can be detected in the arterial phase of enhancement. Necrotic areas appear hypodense on CT scans. Air inclusions signify the infection of a necrotic area (▶ Fig. 7.12).

Fig. 7.10 Chronic pancreatitis. Ultrasound. The pancreatic parenchyma has a very inhomogeneous overall texture. It is permeated by acoustic shadows (echo-free areas, arrows) arising from stippled intrapancreatic calcifications.

Fig. 7.11 Chronic pancreatitis. CT shows atrophy of the pancreas (here, in the body) accompanied by stippled and/or flocculent peri- or intraductal calcifications.

Fig. 7.12 Infected pancreatic necrosis. (a) Colliquative pancreatic necrosis with cellular debris, air inclusions, and fluid levels consistent with infected pancreatic necrosis. (b) Interventional placement of a 16F drain into the infection cavity, with drainage of putrid fluid.

Note

The addition of MRCP to the MRI protocol has replaced ERCP in recent years because it eliminates the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis.

MRCP uses a T2W sequence that depicts fluid-filled structures in the upper abdomen with high signal intensity. Thus, MRCP can provide ERCP-like visualization of the gallbladder and secretion-filled ductal structures, but with noninvasive technique. The progression of chronic pancreatitis can be described in terms of the changes found in the side branches of the main pancreatic duct. The changes begin at the periphery of the side branches, causing distal expansion and obstruction, and then advance toward the main duct, which shows progressive dilatation and irregularities. The diagnostic use of ERCP is still recommended in selected cases, as in patients with suspected autoimmune pancreatitis. Researchers have identified four ERCP criteria that are diagnostic of autoimmune pancreatitis with high sensitivity and specificity 17:

Stenosis of the pancreatic duct involving more than one-third of the duct length.

No distal dilatation of the pancreatic duct.

Dilatation of the side branches.

Multifocal strictures along the full length of the pancreatic duct (“sausage-shaped pancreas”).

ERCP is also used as a minimally invasive therapeutic procedure.

Clinical features Possible symptoms of chronic pancreatitis are recurrent abdominal pain (usually a girdling pain of the upper abdomen), vomiting, jaundice, weight loss, and laboratory tests showing increased activity of serum amylase and serum lipase to more than three times normal values. There may as associated symptoms relating to complications of chronic pancreatitis, such as sepsis, respiratory insufficiency, renal failure, and exocrine and endocrine pancreatic insufficiency due to tissue necrosis. 17

Differential diagnosis Differentiation is mainly required from pancreatic cancer; this cannot always be positively accomplished by imaging. Etiology should also be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Pitfalls Undertaking CT imaging less than 72 hours after onset of symptoms may cause necrosis to be missed. On the other hand, hypoperfusion of the inflamed pancreas at the start of an acute flare may be misinterpreted as necrosis. The most serious error is a delay in diagnosing pancreatic cancer, so that histological confirmation should be obtained whenever uncertainty exists. Pseudoaneurysms that are not diagnosed may become a source of active bleeding.

Key points Abdominal ultrasound is the initial imaging study of choice in chronic pancreatitis. ERCP, MRI/MRCP, and CT can be used to investigate etiology and complications and for follow-up. Chronic pancreatitis always requires differentiation from pancreatic cancer, and equivocal imaging findings require histological confirmation.

Subtype: Autoimmune Pancreatitis

Brief definition Autoimmune pancreatitis is a rare cause of chronic pancreatitis and has been recognized as a separate entity only since 1995. 23 The process involves an elevation of serum immunoglobulins leading systemically to inflammatory fibrosis in multiple organs, including the pancreas. Autoimmune pancreatitis has a nonspecific clinical presentation marked by upper abdominal pain, weight loss, and jaundice. 17, 19, 24 The disease shows excellent response to steroid therapy. 17 Four main histological criteria have been identified 17, 24:

Interstitial fibrosis.

Lymphoplasmacytic infiltration.

Predominantly periductal infiltration.

Periphlebitis.

Imaging signs ERCP and ultrasound can demonstrate segmental or diffuse narrowing of the pancreatic duct along with nonspecific signs such as pancreatic edema. Sectional imaging aids differentiation from pancreatic cancer. Unenhanced MRI in autoimmune pancreatitis shows an area of decreased T1W signal intensity and increased T2W signal intensity in approximately one-half of cases. The area is hypointense in the arterial phase after IV injection of contrast medium, hyperintense in the venous phase in approximately 65% of cases, and hyperintense in the late venous phase (delayed enhancement) in 74% of cases. This hyperintensity in the venous and late venous phases is strongly suggestive of autoimmune pancreatitis. 24 CT does not show corresponding high attenuation in the venous phase, and MRI is therefore superior to CT for this application 24 (▶ Fig. 7.13).

Fig. 7.13 Autoimmune pancreatitis. MRI. (a) T1W image shows a tumorlike lesion that is markedly hypointense to the rest of the pancreas (arrow). (b) Image in the late venous phase shows typical delayed enhancement (arrow).

Differential diagnosis As in other types of chronic pancreatitis, differentiation is mainly required from pancreatic cancer.

7.3 Neoplastic Diseases

The most important pancreatic tumors are reviewed in ▶ Table 7.1.

Exocrine/endocrine | Malignancy | Entities | Frequency (%) |

Exocrine (epithelial) tumors | Malignant | • Ductal adenocarcinoma | 75–90 |

• Adenosquamous carcinoma | 4 | ||

• Intraductal papillary mucinous carcinoma | 3 | ||

• Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma | 1 | ||

• Acinar cell adenocarcinoma | 1 | ||

• Serous cystadenocarcinoma | <1 | ||

• Pancreatoblastoma (in children) | <1 | ||

Borderline | • Mucinous cystic neoplasm with dysplasia | ||

• Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm with dysplasia | |||

• Solid pseudopapillary tumor | |||

Benign | • Serous cystadenoma | ||

• Mucinous cystadenoma | |||

• Intraductal papillary mucinous adenoma | |||

• Mature teratoma | |||

Neuro endocrine tumors | • Insulinoma | ||

• Gastrinoma | |||

• VIPoma | |||

• Glucagonoma | |||

• Somatostatinoma | |||

• Non–hormone-secreting tumors |

7.3.1 Ductal Adenocarcinoma

Brief definition Ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas, commonly known as “pancreatic cancer” or “pancreatic carcinoma,” is by far the most common pancreatic tumor, accounting for 75 to 90% of cases. 2 Approximately 53,070 new cases of pancreatic cancer are expected each year in the United States 25 according to the American Cancer Society. It has the poorest prognosis of all malignancies, with a relative 5-year survival rate of approximately 5%. 26 The etiology of pancreatic cancer is not fully understood. There are risk factors that increase the likelihood that individuals will develop pancreatic cancer at some point during their lifetime; these include nicotine abuse, alcohol abuse, obesity, and chronic pancreatitis. 22, 27, 28 Ductal adenocarcinoma arises from the exocrine pancreas. It invades surrounding structures at an early stage and undergoes early metastasis. 2 Only about 15 to 20% of pancreatic cancers are resectable at the time of diagnosis. A complete R0 resection plus adjuvant chemotherapy is the only treatment strategy that significantly prolongs survival time, achieving 5-year survival rates of 24%. 2, 29, 30, 31 It is essential, therefore, to determine tumor resectability so that patients can be triaged to appropriate therapies. This ensures the best possible prognosis while also sparing patients the risks and morbidity of surgery for unresectable disease. All diagnostic modalities can be used for diagnostic confirmation, TNM staging, and assessment of resectability. ▶ Table 7.2 shows the TNM classification system for pancreatic cancer recommended by the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC). The corresponding stage groupings are shown in ▶ Table 7.3.

Designation | Description |

Primary tumor | |

Tis | Carcinoma in situ |

T1 | Tumor limited to the pancreas, 2 cm or less in greatest dimension |

T2 | Tumor limited to the pancreas, more than 2 cm in greatest dimension |

T3 | Tumor extends past the pancreas but does not invade the celiac trunk or superior mesenteric artery |

T4 | Tumor invades the celiac trunk or superior mesenteric artery |

Lymph nodes | |

N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

N1 | Regional lymph node metastasis (peripancreatic, pancreaticoduodenal, pyloric, splenic hilum, proximal mesenteric and celiac nodes) |

Distant metastasis | |

M0 | No distant metastasis |

M1 | Distant metastasis (liver, lung, skeleton, brain) |

[Table footer – please overwrite] | |

Stage | Groupings |

0 | Tis N0 M0 |

I | T1 N0 M0 to T2 N0 M0 |

• IA | T1 N0 M0 |

• IB | T2 N0 M0 |

II | T3 N0 M0 to T1–T3 N1 M0 |

• IIA | T3 N0 M0 |

• IIB | T1–T3 N1 M0 |

III | T4 Any N M0 |

IV | Any T Any N M1 |