Multidetector CT is the imaging method of choice for evaluation of pancreatitis and competes with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for detection and staging of pancreatic tumors. Rapid CT acquisition times allow high-resolution multiphase scanning of the entire pancreas within a single breath hold in most instances.

CT Technique

CT evaluation of pancreatitis is usually performed as a routine abdomen scan with extension of CT scanning of the pelvis if large fluid collections are present. Water may be substituted for oral contrast agents if stones in the distal part of the common bile duct are suspected. CT evaluation for a pancreatic mass is performed as a multiphase dynamic scan of the entire pancreas. Optimally each phase is performed during a single breath hold. Oral contrast agents are routinely given. CT without an intravenous contrast agent is performed from the liver dome through the iliac crest, reconstructing thin slices (1.25–3.0 mm) with sagittal and coronal reconstructions. A power injector is used to administer 120 to 150 mL of intravenous contrast agent at 4-5 mL per second. The arterial phase scan is obtained at 30 to 35 seconds following onset of injection. Both the liver and the pancreas show arterial opacification with minimal contrast enhancement of the portal vein. The venous phase scan of the entire abdomen is obtained at 60 to 70 seconds following initiation of contrast agent injection. Delayed scans may be obtained at 3 to 5 minutes after contrast agent injection through the liver and kidneys. Three-dimensional reconstructions may be performed as CT angiograms.

Normal Anatomy of the Pancreas

The pancreas lies within the anterior pararenal compartment of the retroperitoneal space, behind the left lobe of the liver and the stomach, and in front of the spine and great vessels ( Fig. 13.1 ). The peritoneum-lined lesser sac forms a potential space between the stomach and the pancreas. The pancreas is divided anatomically into four parts: head, including the uncinate process, neck, body, and tail. The pancreas somewhat resembles a question mark turned on its left side, with the hook portion formed by the pancreatic head and uncinate process as they lie cradled in the duodenal loop. The portal vein fills the center of the hook. The uncinate process cradles the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) and tapers to a sharpened point directed leftward beneath the SMV. The neck is a slightly constricted portion of the pancreas just ventral to the portal vein confluence formed by the junction of the SMV and the splenic vein. The body and tail taper as they extend toward the splenic hilum. The pancreas is usually directed upward and to the left, although it may form an inverted-U shape with the tail directed caudad. Sequential CT slices must be mentally summated to assess the shape and size of the pancreas. The gland is 15 to 20 cm long. The maximum width is 3.0 cm for the head, 2.5 cm for the body, and 2.0 cm for the tail. The gland is larger in young people and progressively decreases in size with age. The CT attenuation is uniform and approximately equal to that of muscle. In young patients the pancreas resembles a slab of meat. Progressive infiltration of fat between the lobules of the pancreas gives it a feathery appearance with advancing age. The pancreatic duct is best visualized with thin slices (1.25–2.5 mm). It tapers smoothly to the tail, measuring a maximum of 3.5 mm in diameter in the head, 2.5 mm in the body, and 1.5 mm in the tail. The main duct (of Wirsung) joins the common bile duct at the sphincter of Oddi to enter the duodenum. The accessory duct (of Santorini) draining the anterior and superior portions of the pancreatic head drains into the duodenum via the minor papilla.

The complex vascular anatomy of the pancreas must be understood to correctly interpret pancreatic CT scans. The splenic vein runs a relatively straight course in the dorsum of the pancreas from the splenic hilum to its junction with the SMV just posterior to the neck of the pancreas. The plane of fat between the splenic vein and the pancreas must not be mistaken for the pancreatic duct. The splenic artery runs an undulating course through the pancreas from the celiac axis to the spleen. Atherosclerotic calcifications are common in the splenic artery and may be easily mistaken for pancreatic calcifications. The superior mesenteric artery (SMA) arises from the aorta dorsal to the pancreas and courses caudally, surrounded by a collar of fat. The SMV courses cranially, just to the right of the SMA, until it joins the splenic vein to form the portal vein. The pancreatic head entirely surrounds this junction, with the uncinate process extending beneath the SMV. The portal vein courses upward and rightward with the hepatic artery and the common bile duct to the porta hepatis.

Pancreas Divisum

The most common anomaly of the pancreatic ductal system is pancreas divisum, which is present in 4% to 10% of the population. In this anomaly, as a result of failure of fusion of the dorsal and ventral pancreas during embryologic development, the dorsal duct draining most of the pancreas empties into the minor papilla via the duct of Santorini rather than into the major papilla via the duct of Wirsung. Thin-section multidetector CT shows the dorsal pancreatic duct coursing posterior to the descending portion of the common bile duct cephalad to the sphincter of Oddi ( Fig. 13.2 ). The distal portion of the dorsal pancreatic duct may be dilated at the junction with the duodenum, an anomaly known as a santorinicele . In most patients pancreas divisum is an incidental finding of no significance. However, the constriction of the dorsal duct at the minor papilla predisposes to recurrent pancreatitis in 25% to 38% of patients with pancreas divisum.

Annular Pancreas

Incomplete rotation of the embryologic ventral pancreas results in a segment of the pancreas encircling and often constricting the descending duodenum. Annular pancreas is rare, occurring as an isolated anomaly or in association with other congenital anomalies. It may present in the neonatal period with duodenal or biliary obstruction. In adults it may present with ulcer disease, duodenal obstruction, or pancreatitis. CT shows pancreatic tissue encircling the second portion of the duodenum ( Fig. 13.3 ). Symptomatic cases warrant surgical correction.

Fatty Infiltration of the Pancreas

Fatty infiltration of the pancreas occurs commonly with aging and obesity without affecting the function of the pancreas.

- •

Because the gland is not encapsulated, fatty infiltration between the lobules in older adult patients gives the pancreas a delicate, feathery appearance resembling a dust mop ( Fig. 13.4 ).

FIG. 13.4

Fatty infiltration of the pancreas.

The pancreas (arrowheads) shows fat infiltrating between the atrophic lobules of parenchyma. Despite diffuse atrophy and fatty infiltration, the exocrine and endocrine functions of the pancreas were normal in this elderly patient. Note the vascular landmarks of the pancreas, the portal vein confluence (PV) and the splenic vein (SV).

- •

Fatty replacement may be diffuse or distributed unevenly throughout the pancreas. The head and uncinate process are common areas of focal sparing of fat infiltration. In some cases the head and uncinate process are involved and the remainder of the pancreas is spared.

- •

In advanced cystic fibrosis the pancreatic parenchyma is atrophic and is diffusely replaced by fat ( Fig. 13.5 ), while exocrine function of the pancreas is severely impaired. The revised Atlanta classifica tion also updates confusing terminology used to describe pancreatitis and peripancreatic fluid collection. It discourages the use of the terms acute pancreatic pseudocyst and pancreatic abscess.

FIG. 13.5

Cystic fibrosis.

Image of the pancreatic head in a patient with cystic fibrosis showing near complete atrophy of the pancreatic parenchyma (arrowheads) with replacement by fat. This is a common CT finding in patients with cystic fibrosis. A , Superior mesenteric artery; Ao , abdominal aorta; V , superior mesenteric vein.

Acute Pancreatitis

Inflammation of the pancreas damages acinar tissue and leads to focal disruption of small ducts resulting in leakage of pancreatic juice. The absence of a capsule around the pancreas allows easy access of pancreatic secretions to surrounding tissues. Pancreatic enzymes digest through fascial layers to spread to multiple anatomic compartments. Acute pancreatitis in adults is most often caused by passage of a gallstone or by alcohol abuse ( Table 13.1 ). The incidence of acute pancreatitis continues to increase. Acute pancreatitis may progress to recurrent acute pancreatitis then to chronic pancreatitis. The diagnosis of pancreatitis is made clinically by the presence of acute abdominal pain and elevated serum amylase and lipase levels. The role of CT is to document the presence and severity of disease and complications. Severity of CT findings correlates with prognosis. Demonstration of necrotic pancreatic tissue is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Other prognostic factors associated with increased risk of complications include age, gallstone disease, and organ failure on admission. The 2012 revision of the Atlanta Classification for Acute Pancreatitis divides the disease into two distinct subtypes.

|

Interstitial edematous pancreatitis (IEP) accounts for 90-95% of cases of acute pancreatitis. Inflammation is present without necrosis.

- •

Post-contrast CT findings include diffuse or localized enlargement of the pancreas due to edema. The entire pancreatic parenchyma enhances ( Fig. 13.6 ). Enhancement of the parenchyma may be homogeneous and normal or slightly heterogeneous. Peripancreatic inflammatory changes and fat stranding may be present associated with peripancreatic fluid of varying volumes.

FIG. 13.6

Interstitial edematous pancreatitis.

The pancreas (P) is mildly swollen, but all of the pancreatic parenchyma enhances normally. Edema and inflammation (arrowheads) infiltrate the peripancreatic tissues.

- •

Acute peripancreatic fluid collections ( Fig. 13.7 ) associated with IEP are defined as non-encapsulated, non-enhancing, low attenuation, liquefied collections without solid components shown on CT performed within 4 weeks of onset of symptoms. No necrotic tissue is present. Walls surrounding the collection are imperceptible.

FIG. 13.7

Acute peripancreatic fluid collection.

Postcontrast CT image of the pancreatic head (P) at 3 weeks following the onset of symptoms revealing unencapsulated non-enhancing peripancreatic fluid collections (arrowheads) . Vascular landmarks include the superior mesenteric vein (v) and superior mesenteric artery (a) .

- •

Pseudocysts associated with IEP are defined as homogeneous simple fluid collections with visible walls seen after 4 weeks from onset of symptoms ( Fig. 13.8 ). Pseudocysts contain only fluid. The presence of any fat or soft tissue indicates the collection is walled-off necrosis (WON) not a pseudocyst.

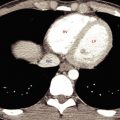

FIG. 13.8

Pancreatic pseudocyst.

(A) Axial postcontrast CT at 6 weeks following the onset of symptoms shows a persisting fluid collection (PC) anterior to and compressing the pancreas (P) . The stomach (St) is compressed and displaced anteriorly, whereas the duodenum (Du) is displaced laterally. The common bile duct (arrowhead) is seen in the pancreatic head. (B) Sagittal reconstructed image from the same CT study providing better demonstration of the capsule (arrows) of the pseudocyst ( PC ).

- •

Fluid collections associated with IEP generally do not require drainage unless they become infected. The presence of gas within the collection is evidence of infection and the need for drainage.

Necrotizing pancreatitis accounts for 5-10% of cases of acute pancreatitis. CT shows three morphologic forms of acute pancreatic necrosis. Pancreatic necrosis is best assessed on early-phase post-contrast CT images performed at 40 seconds post injection. CT is most sensitive to necrosis at 72 hours following the onset of symptoms. The hallmark of necrosis is absence of enhancement of pancreatic parenchyma and/or surrounding tissues.

- •

Pancreatic parenchymal necrosis with peripancreatic necrosis accounts for 75-80% of cases ( Fig. 13.9 ). CT shows lack of parenchymal contrast enhancement and heterogeneous non-liquefied areas of nonenhancement in the peripancreatic tissues, especially in the lesser sac and retroperitoneaum.

FIG. 13.9

Necrotizing pancreatitis.

Liquefaction necrosis has completely destroyed the pancreas, replacing it with a loculated collection of fluid (F) in the pancreatic bed anterior to the splenic vein (arrowhead) .

- •

Pancreatic necrosis alone (5%) appears as focal or diffuse areas of absent parenchymal enhancement without associated collections.

- •

Peripancreatic necrosis alone (20%) appears on CT as non-enhancement of peripancreatic tissues with normal enhancement of all pancreas parenchyma. Peripancreatic collections contain liquefied and non-liquefied components.

- •

Acute necrotic collections (ANC) associated with necrotizing pancreatitis ( Figs. 13.10 and 13.11 ) are defined as heterogeneous collections containing necrotic pancreatic parenchyma, hemorrhage, and necrotic fat seen on CT performed within 4 weeks of onset of symptoms. Collections may be within or surrounding pancreatic parenchyma or both.

FIG. 13.10

Acute necrotic collections.

Fluid collections resulting from acute pancreatitis extend from the necrotic pancreas into the lesser sac (LS) , compressing the stomach (St) and extending partially around the gallbladder (GB) . The distal part of the pancreatic duct (arrowhead) is dilated. The CT image was obtained at 3 weeks following the onset of symptoms.

FIG. 13.11

Acute necrotic collection.

Pancreatic fluid (F) and inflammation extend from the pancreas in the anterior pararenal space (APS) partially around the left kidney between the leaves of the posterior renal fascia (arrowheads) . Note that the perirenal space (PRS) and the posterior pararenal space (PPS) are spared.

- •

Walled-off necrosis (WON) is defined as an ANC that develops an enhancing wall and is seen on CT performed after 4 weeks from onset of symptoms ( Fig. 13.12 ). WONs are heterogeneous and complex in appearance because of debris and variable amounts of necrotic tissue.

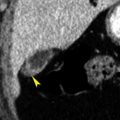

FIG. 13.12

Walled-off necrosis.

CT image obtained at 6 weeks showing an encapsulated heterogeneous fluid collection (F) occupying the bed of the pancreas, which is completely necrotic except for the pancreatic head (P) . The thin enhancing wall (yellow arrowheads ) is clearly visible. Necrotic debris (red arrows) is subtly higher in attenuation than the fluid in which it resides. The superior mesenteric artery (a) enhancing normally.

- •

Necrotic tissue is highly likely to become infected. CT demonstration of gas within a necrotic collection is strong evidence of infection. Percutaneous aspiration and drainage are needed to treat infected necrotic collections.

Organ failure and other complications commonly occur with acute pancreatitis. If no complications or organ failure is present the disease is defined as mild . Organ failure lasting less than 48 hours defines the disease as moderate . Severe disease is associated with single or multiple organ failure lasting 48 hours or longer. Organ failure includes impaired respiratory, cardiovascular, or renal function. Complications of acute pancreatitis include the following.

- •

Secondary infection occurs in 30-70% of patients with bacterial growth within necrotic tissues and fluid collections most commonly 2-3 weeks after onset of disease. Infection greatly worsens the prognosis with mortality rates of 20-30% for infected necrosis versus 5-10% for sterile necrosis. Fluid collections containing gas ( Fig. 13.13 ) are suspicious for infection, but infected fluid collections may be indistinguishable from sterile fluid collections. Wall enhancement is not reliable as a sign of infection. CT, US, or endoscopic US-guided aspiration is needed to confirm diagnosis. Terms such as pancreatic abscess , phlegmon , organized necrosis , necroma , or sequestration are discouraged by the Atlanta Classification nomenclature.

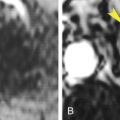

FIG. 13.13

Secondary infection.

Marked enlargement of the pancreatic head (PH) caused by acute pancreatitis is complicated by a small fluid collection (yellow arrowhead) containing bubbles of gas (red arrow) indicating acute infection. Inflammatory edema partially envelops the superior mesenteric vein (v) and superior mesenteric artery (a) . T , tail of the pancreas.

- •

Hemorrhage is caused by erosion of blood vessels or bowel. It is seen as high attenuating fluid in retroperitoneum or peritoneal cavity. Hemorrhage commonly accompanies necrosis.

- •

Pseudoaneurysms are encapsulations of arterial hemorrhage with continued communication with eroded artery. Swirling and “to and fro” blood flow continue within the pseudoaneurysm. Risk of massive hemorrhage is high. A pseudoaneurysm must be excluded with contrast-enhanced CT ( Fig. 13.14 ) or Doppler US prior to percutaneous puncture of pancreatic fluid collections. Pseudoaneurysms occur in 3-10% of patients with acute pancreatitis.

FIG. 13.14

Pseudoaneurysm.

In a patient with acute pancreatitis, postcontrast coronal reconstruction CT shows a lobulated enhanced pseudoaneurysm (arrowheads) arising from the splenic artery (arrow) . Anatomic landmarks include the aorta (Ao) , the inferior vena cava (IVC) , the tail of the pancreas (P) , and the spleen (S) .

- •

Thrombosis of the splenic vein and other peripancreatic vessels occurs as a result of the inflammatory process. The thrombosed veins are distended with low attenuation thrombus and fail to enhance on venous phase scans.

- •

Disconnection of the pancreatic duct may occur as a result of necrosis resulting in a viable segment of pancreas, usually in the neck region, being disconnected from the intestinal tract. A fistula develops which continues to leak pancreatic fluid and enzymes into peripancreatic spaces.

- •

Pancreatic ascites is caused by leakage of pancreatic juice into the peritoneal cavity inducing secretion of fluid from peritoneal membranes. Pancreatic ascites contains a high level of amylase.

- •

Recurrence of acute pancreatitis occurs in half of the patients in whom the cause is alcohol abuse.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree