19 Pancreatic Interventions Due to its retroperitoneal position, the pancreas is difficult to reach using all of the conventional surgical techniques, including open or laparoscopic surgery. From the endosonographic point of view, however, it is only a few millimeters from the transducer—a distance corresponding to the thickness of the duodenal or gastric wall. The development of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) therefore led to the development of EUS-guided interventions in the pancreas. These interventions almost always relate to peripancreatic fluid collections, usually resulting from acute or chronic pancreatitis. In the early 1980s, for patients with chronic pancreatitis, the alternatives to letting the process run its spontaneous course, on the one hand, and carrying out pancreatectomy with unsatisfactory results on the other, included surgical drainage procedures with dilation of the pancreatic duct in cases of obstruction. At about the same time, alternative techniques were developed, with the objective of making the resection less radical and the drainage less invasive: resection of the head of the pancreas, preserving the duodenum, and endoscopic decompression using pancreatic papillotomy, extraction of stones, and stent placement. At the same time, as part of the new endoscopic treatments for chronic pancreatitis, the first endoscopic transpapillary and transmural drainage procedures were carried out in pancreatic pseudocysts. These endoscopic techniques have been found to be technically successful, with low complication rates, and not just in individual cases. It has also been established that successful puncture and drainage can at least reduce the often considerable symptoms. This form of treatment has developed substantially, particularly with the aid of endosonography. Cystic Pancreatic Lesions: Definition and Classification Pathological cavities in the region of the pancreas can be classified using a wide variety of characteristics. In clinical practice, lesions can be described from various points of view (Table 19.1),1–4 although the characteristics of one category (e.g., size) do not necessarily allow conclusions to be drawn about another category (such as the prognosis). This situation has led to some uncertainty regarding the classification and definition of cystic lesions of this type. The most important questions in clinical practice are answered by simple sonomorphological characterization of the lesions with regard to shape, size, position, and echo pattern. This applies in particular when the technique also provides information about the topographical and pathological anatomy of the vessels and of the pancreatic and bile ducts, and when information about the development of the cysts can be obtained over a period of a few weeks. Information of similar value to that provided by ultrasound can also be obtained with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT). A second classification according to etiology and pathogenesis can be made on the basis of the sonomorphology and medical history, but sometimes not until endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or histological assessment have been carried out (Table 19.2). Awareness of these differential-diagnostic alternatives is important during the endoscopic drainage of cystic lesions. In particular, cystic neoplasias must not be over looked. Even acute or chronic pancreatitis can cause or possibly be the consequence of a pancreatic carcinoma.

Criteria | Terms used |

Medical history, age | Acute/chronic, mature/immature |

Underlying illness | Post-pancreatitis, idiopathic, neoplastic |

Symptoms | Symptomatic/asymptomatic |

Size | Microcystic, large (>6cm), small (≤ 6 cm) |

Shape | Monocystic/polycystic, causing bulging/no bulging, septate/nonseptate |

Image of contents | Anechoic/hypoechoic/echogenic |

Content as aspirate | Serous, liquid, mucinous, putrid, hemorrhagic (“chocolate cyst”), solid, infected/sterile, amylase present/absent |

Boundaries | With/without wall, sharply/poorly delineated, arched-round, complex/branched |

Connections | With/without fistula to: pancreatic duct, stomach, ascites, retroperitoneum, pleura, mediastinum, other cysts |

Position | Intrapancreatic/extrapancreatic, head-body-tail |

Malignancy | Benign/malignant |

Diagnosis | Comments |

Result of pancreatitis | Pseudocysts and other lesions (see the Atlanta classi.cation, Table 19.3) |

Duodenal wall cysts | Intramural. Genesis unclear; caused by ectopic pancreas or in.ammation of the head of the pancreas? |

Idiopathic pancreatic cysts | Rare, sporadic, or in polycystic disease |

Cystic pancreatic tumors | Microcystic or macrocystic, serous or mucinous. Malignancy in principle unclear |

Genuine pancreatic cysts | Rare, probably mostly IF |

Pancreas duplication cysts | Rare, benign1 |

Lymphocele | Benign, rare, in parenchyma; the surroundings are normal, the edges smooth and very delicate, no wall2 |

Hydatid disease | |

Wall abscess | Rare; endoscopic ultrasound demonstrates the position in the wall of the stomach |

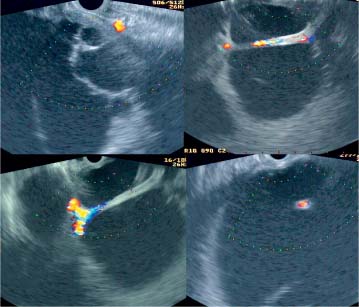

Malignant pancreatic tumors, the prevalence of which among cystic pancreatic processes is estimated to be ≈ 5–10%, are the most important differential diagnosis. Detailed descriptions of the classification and diagnosis of cystic pancreatic tumors have recently been published.5–7 Serous or mucinous neoplasia should always be considered; they cannot always be recognized by the typical microcystic or polycystic shape or by mucous filling of the duct (Figs. 19.1, 19.2, 19.3, and 19.4).8

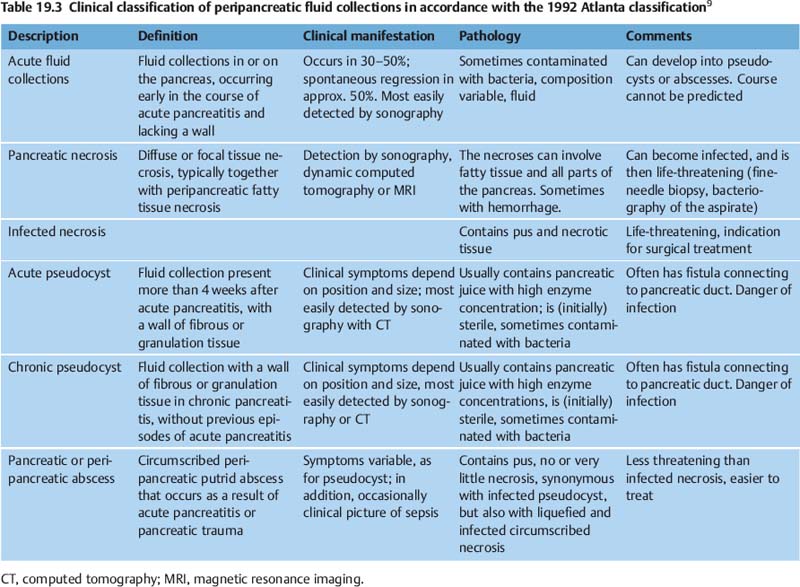

The most accurate method of imaging various cystic lesions is endosonography. By far the majority of peripancreatic fluid collections are the result of episodes of pancreatitis. Following less convincing attempts to classify pseudocysts systematically, the classification shown in Table 19.39 was finally proposed for fluid collections caused by pancreatitis, as part of the Atlanta classification of acute pancreatitis. The Atlanta classification includes the common postacute fluid collections, which are not sharply delimited and often resolve spontaneously, and are filled with clear (anechoic) fluid; pseudocysts surrounded by a fibrous wall; and necroses— three findings that can also be differentiated very easily on a clinical basis. In practice, however, such pure findings are the exception, and transitional states are the norm. If it is difficult even to draw a clear line between acute pancreatitis and acute episodes of chronic pancreatitis, it is certainly difficult and unreliable to attempt a clear clinical classification of their “cystic” complications, with superimposition of older and more recent findings, liquid and solid, echogenic and hypoechoic, sterile, contaminated and infected (purulent) cysts with more or less well-defined walls (and anatomic delimitation). Despite these limitations, the Atlanta classification is currently the best and only clinically useful classification of pancreatogenic cysts, precisely because it bows to practice and attempts to use different categories to do justice to the characteristics of quite different types of cyst.

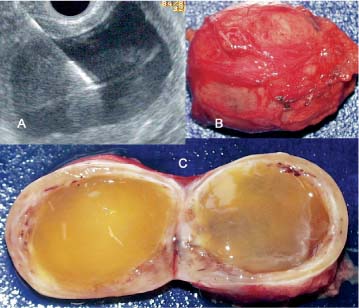

Fig. 19.1 Polycystic serous pancreatic adenoma. Endosonography, radial scanner (3670 UR). The tumor as a whole has a roundish border. It displays larger cysts, but also honeycombed, microcystic areas. The surrounding pancreatic parenchyma is normal.

The classification proposed by Nealon and Walser in 200210 is based solely on the anatomy of the pancreatic duct:

• Type I: normal duct, no communication with the pseudocyst

• Type II: normal duct, communication with the pseudocyst

• Type III: otherwise normal duct with stricture, no communication with the pseudocyst

• Type IV: otherwise normal duct with stricture, communication with the pseudocyst

• Type VI: otherwise normal duct with complete cut-off

• Type VII: chronic pancreatitis, no duct-pseudocyst communication

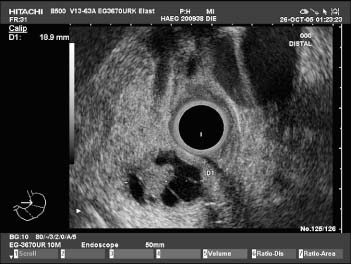

Fig. 19.2a–c A mucus-producing pancreatic tumor.

a The tumor was revealed by a fishmouth papilla. The viscous mucus forced the pancreatic ostium wide open.

b The mucus filled the pancreatic duct system, which had a cystically dilated appearance on EUS (longitudinal scanner, 7.5 MHz, Pentax FG38-UX, Pentax, Hamburg, Germany).

c The corresponding endoscopic retrograde cholangiogram.

Fig. 19.3 A huge cystic retroperitoneal finding dorsal to the stomach, with anechoic contents, delicate septa, and unusually with arteries flowing through the lumen. There was no definite pancreatitis in the medical history, and no changes in the pancreatic parenchyma as found in chronic pancreatitis. Transmural drainage was not performed due to the suspect finding, and open surgery was performed instead. Histological analysis showed that the lesion was a benign pseudocyst.

This classification addresses the important and previously unclear issue of the influence of communications between the pancreatic duct and the fluid collection on the treatment strategy and its chances of success. Using their own retrospective data, the authors show that percutaneous drainage has little chance of success when a communication is present.

The present authors have not found that it is beneficial to make the treatment procedure dependent on the existence of this type of communication, particularly since the existence of a fistula of this type is often difficult to establish and even more difficult to rule out. This fact is also reflected in the large differences between the values for the prevalence of such fistulas reported by different authors. The values vary between 6%, cited by Neoptolemos,11 20% by Barthet et al.,12 and up to 60% by Nealon et al.13 Large pseudocysts or necrotic cavities, inflammatory swelling of the head of the pancreas or of the duodenal wall, or scarring and calcification in chronic pancreatitis can change the normal anatomy to such an extent that endoscopic retrograde pancreatography (ERP) is impossible or very difficult. Even if the pancreatic duct can be examined, fistulas often cannot be clearly identified due to compression caused by the cystic lesions and calcification. In addition, a high level of injection pressure is often required, and—especially for very large pseudocysts—large quantities of contrast agent are needed to clearly identify the communication between the pancreatic duct and pseudocyst, necrotic cavity, or even stomach, mediastinum, abdominal cavity, or bile duct. We avoid this sort of procedure, which involves a substantial risk of introducing bacterial contamination (almost always) or manifest septic complications. In addition, the anatomy can often be imaged without any problems following decompression of the pseudocyst or necrotic cavity. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is not capable of detecting narrow fistulas in complex anatomy either, so it is not an alternative to ERCP. On the other hand, if the latter is easy to do and shows a clear communication between the duct and the pseudocyst, transpapillary drainage is often successful on its own. It has not been demonstrated whether, in such cases, it is better to fit the pancreatic duct with a stent to bridge the fistula (our preference, which we like to combine with transmural drainage) or to drain the cyst directly through the fistula.

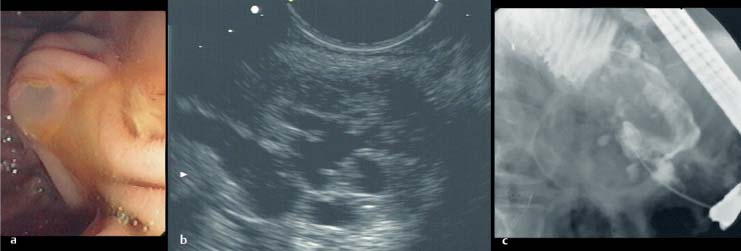

Fig. 19.4a–c a A cystic lesion in the body of the pancreas with a strong wall, thickened dorsally, and anechoic contents, in a 46-year-old patient with no signs of acute or chronic pancreatitis in the medical history or abdominal ultrasound findings. The symptoms included a slight pulling sensation during vigorous movement. b, c Surgically, a previously unreported type of pancreatic ganglioneuroma was enucleated.8 EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration revealed highly viscous mucus. The course was uncomplicated. This example shows how difficult it can be to distinguish between cystic lesions following pancreatitis and neoplastic lesions.

None of the classifications of cystic lesions mentioned is suitable for stratifying patients according to the severity of the condition. In clinical practice, an overview of aspects covered by the individual classifications, the serum C-reactive protein (CRP) level, and symptoms during the course of the illness provide a tried-and-tested basis for the treatment strategy.

Pseudocysts are typical complications of chronic pancreatitis. They are found in up to 60% of surgical specimens from patients with chronic pancreatitis, and, according to Stolte,14 more often in preparations with segmental (48%) than with nonsegmental (23%) chronic pancreatitis. In large clinically recorded populations with chronic pancreatitis, pseudocysts have been described in 23% of patients (56 of 245).15 These data relate to a symptomatic and consequently treated population (usually treated surgically). The actual prevalence of pancreatic pseudocysts and other cystic lesions in chronic pancreatitis, including uncomplicated courses, is presumably substantially lower.

Values cited for the incidence of peripancreatic fluid accumulations in acute pancreatitis lie between 14%16 and (when detected with CT) over 50%.17

Pancreatic necroses develop in ≈ 5% (17 of 348)18 to 20% (38 of 194)19 of patients with acute pancreatitis. Up to 70% of them have primary infection. In recent publications, the mortality rate due to infected necroses has been reported to be 10–35%.

In 100 patients included in a study in Glasgow,20 the mortality rate due to pseudocysts of biliary origin, at 22%, was distinctly higher than for pseudocysts of alcoholic origin, at 5%. The overall figure was 12%; only patients with postacute pseudocysts who had undergone surgery were included. In most cases, the cause of death was sepsis or hemorrhage. All patients with chronic pseudocysts survived. A mortality rate of 5–15% has generally been reported for cystic lesions following pancreatitis. However, it is scarcely possible to give a figure for the spontaneous course, as the patients detected epidemiologically have usually been treated and thus represent a selection.

With very few exceptions, the data shown here apply to “publication-relevant” groups of patients in fairly large centers—i.e., only to the more severe courses of the clinical pictures concerned. The incidence and prevalence of problems and complications may therefore have been over estimated. However, selection of this sort also applies in general to patients, including those undergoing interventional treatment.

Peripancreatic or intrapancreatic fluid collections can have various origins and are probably often the result of several pathological mechanisms working together.

Severe acute pancreatitis gives rise to peripancreatic fatty tissue necroses, occasionally with large fields of necrosis surrounding the pancreas like a coat and spreading along the fibrous tissue septa to the intrapancreatic fatty tissue, on the one hand, and to the more distant extrapancreatic fatty tissue (mesentery, omental bursa, retroperitoneum) on the other. Pseudocysts containing hemorrhagic and necrotic material develop from the larger necrosis fields within 7–30 days of the acute necrosis. With time, they separate themselves more clearly from their surroundings through the formation of granulation tissue. In most cases, they communicate with the pancreatic duct. Confluent intrapancreatic fatty tissue necroses are usually replaced by sclerotic tissue. This fibrotic process can involve the interlobular pancreatic ducts and encourage the development of chronic pancreatitis. Intrapancreatic pseudocysts can also persist due to communication with the ductal system and lead to local complications due to compression of the environment. In dogs, it has been shown that a pseudocyst takes ≈ 6weeks to develop a “mature” fibrous wall.

Post-traumatic pancreatic pseudocysts are not common; in large populations, they represent a maximum of 5%. In children, they mainly occur after pancreatic rupture due to car accidents or due to trauma from bicycle handlebars. If the pancreatic duct remains continuous, spontaneous regression is possible.

Despite important recent evidence concerning the genetic and autoimmune pathogenesis of acute and chronic pancreatitis, the concept of more or less mechanical development is still the most important idea guiding the therapeutic procedure and the patient’s well-being. Stolte’s discussion of this subject from 1984,14 based on thorough morphometric investigations, remains valid: whatever the nature of the etiology or course of the pancreatitis, “in the end, there is always an area of scar tissue. So the various subdivisions of chronic pancreatitis, with their histological types and duct patterns only appear to be snapshots of a continuous, progressive process… There is a vicious circle of self-perpetuation in chronic pancreatitis. “The fact that a persistent fistula, traumatic rupture of the duct, and pancreas divisum are established causes or contributing factors in the formation of pseudocysts supports the view that the impaired flow is at least partly mechanical in origin.

Any therapeutic intervention has to be weighed up in comparison with alternative treatments. Surgical or endoscopic interventions are onlyjustified if their risk is lower than that of the spontaneous course or of noninvasive approaches. Different therapeutic strategies, including open surgery, have to be discussed with the patient to provide a basis for informed consent to any therapy. These alternatives are therefore considered here.

As in the treatment of chronic pancreatitis in general, a treatment strategy for pancreatogenic cystic lesions can serve very different purposes. As emergency treatment in acute complications such as rupture or hemorrhage, the objective is to avert the immediate danger, which is almost always achieved by surgery and does not require any discussion. In the case of infected pseudocysts or necroses, the prevention of life-threatening septic complications is without question an absolute indication for therapeutic intervention. The situation is similar for compression stenoses of the bile duct, duodenum, or stomach, which require surgery.

The most common reason for surgical treatment of pseudocysts is severe pain, followed by nausea and vomiting (as a consequence of the above-mentioned compression of the gastric and intestinal lumen), loss of weight, and jaundice. However, in the surgical literature, clear reference to the indications or the objectives of the intervention is not always made.

In asymptomatic or oligosymptomatic patients with large or persistent cysts, the prevention of likely complications of the spontaneous course (see below) always influences the therapeutic objectives, although there are no reliable data regarding the incidence of these. The complications can also be considered to include loss of the endocrine or exocrine function of the pancreas. In this case, maintaining the function of the organ (or preventing its loss in the “natural” course of the disease) would be the therapeutic objective. In the context of organ conservation, the treatment of cystic lesions—which is justified even for isolated lesions for improvement of symptoms—should be understood as only part of the decompressive and drainage treatment of the chronic pancreatitis. In this way, surgery has achieved encouraging results.21–23 Endoscopic interventions are generally based on the hypothesis that reconstructing the normal anatomy, usually by drainage of congested regions, and restoring the normal flow of pancreatic juice can lead to an improvement in the symptoms and sometimes of the entire clinical course. In a multicenter retrospective analysis of more than 1000 patients with chronic pancreatitis, the symptoms improved in the long term in 65% of patients and in the short term in 85%.24

The expected spontaneous course of a pancreatic pseudocyst depends on the time of observation. If a iquid lesion develops during the acute phase of pancreatitis, it is very probably peripancreatic edema with a good chance of spontaneous regression. Clinically, acute fluid collections of this type can correspond to a pseudocyst.

Spontaneous regression rates of 7%,8 12%,25 28%,26 and 60%27,28 have been reported, sometimes depending on the size of the cyst. According to some authors, spontaneous regression of pseudocysts is unlikely after more than 6 weeks. On the other hand, Vitas and Sarr, who retrospectively analyzed patients with pancreatic pseudocysts who were treated at the Mayo Clinic in the years 1980–85, came to a different conclusion.29 Of 114 patients, 46 were given primary treatment by surgery. Only six (9%) of the remaining 68 patients, who were treated conservatively, had serious complications during a mean observation period of 46 months; 19 of them ultimately underwent elective surgery. Overall, the pseudocyst regressed spontaneously in 57% of the patients treated conservatively, in 38% of them more than 6 months after the diagnosis. Among these, seven patients had cysts more than 10 cm in diameter which regressed without complications. The authors conclude that, contrary to the earlier view, even older and very large pseudocysts can regress spontaneously; that a “wait-and-see” approach is therefore justified in most patients.

Relevant complications of the spontaneous course include hemorrhage, rupture, and infection. The incidence of these is difficult to specify, as it is normal to try to avoid such complications using surgical treatment. No reports on the spontaneous course in large populations of patients over prolonged observation periods are available.

Hemorrhagic complications—which can manifest as hemosuccus pancreaticus, and also as fulminant hemorrhage into a pseudocyst or as a consequence of cyst rupture—mostly arise from the splenic artery. The artery is affected by local reactions resulting from pancreatitis and can develop pseudoaneurysms as a typical complication in ≈ 3% of patients. Rupture of the pseudoaneurysm then leads to arterial bleeding. Major arteries originating from the celiac trunk, and not infrequently the splenic artery or hepatic artery, often pass directly by the walls of cystic lesions. They can be clearly seen there using ultrasonography even without Doppler imaging, whereas smaller vessels can only be seen with EUS. The splenic vein lies in the immediate vicinity in most cases of pancreatitis and pseudocysts. If it is affected by the inflammatory process, the typical complication is splenic vein thrombosis. This is apparent from the almost pathognomonic endoscopic picture of isolated gastric varices (without esophageal varices), sometimes together with duodenal varices. Bleeding varices can develop as life-threatening sequelae. The literature contains a large number of case studies on this topic, but there is no reliable information on the incidence of such vascular and hemorrhagic complications.

The same applies to spontaneous rupture of pseudocysts. Sankaran and Walt30 observed spontaneous rupture in 19 of 131 pseudocysts (15%), with hemorrhage in four cases. Because of the high rate of spontaneous complications (33%), the authors advocate surgical drainage. Such a high rate of spontaneous complications has not been confirmed in the few other papers on the spontaneous course. Nevertheless, Seiler et al.,31 on the basis of 154 patients with complicated chronic pancreatitis, describe the formation of pseudocysts as the most important prognostic risk factor, correlating highly significantly not only with pain but also with a higher incidence of vascular complications and a significantly higher risk of mortality (7.1%) than for patients without pseudocysts (1.8%).

There have been isolated reports of fistulas to the stomach, and of the spread of pseudocysts into the mediastinum with rupture or fistula into the esophagus, pseudoachalasia, or cardiac compression.

There is no reliable information on the incidence of spontaneous infection of initially sterile pseudocysts. Kolars et al.32 found bacterial infection in 17 of 51 (33%) pseudocysts, although this was in a group of hospitalized patients who later underwent surgery—i.e., certainly not a representative population.

Imrie et al.20 reported a mortality rate of 22% for patients with pancreatic pseudocysts of biliary origin (27% of the group), significantly higher than the mortality rate of 5% for pseudocysts of alcohol-induced origin (59% of the patients). In 1979, Bradley et al.33 recommended that pseudocysts should not be kept under observation for long, as 41% of 54 patients with pancreatic cysts developed complications after an observation period of 2–4 months, with a mortality rate of 14%—higher than with surgical intervention.

Patients with symptomatic cystic lesions have generally already undergone weeks or months of conservative treatment by various hospitals and doctors, require high doses of analgesics, and have undergone prolonged hospital stays and periods of fasting, often with parenteral feeding. They are referred because of the failure of these treatments. For most of the patients encountered here, conservative treatment is no longer a genuine alternative; instead, they specifically represent “the failures of the waiting game.”34

Although treatment with somatostatin analogues has been repeatedly suggested for chronic pancreatitis, the usefulness of these agents has at best been demonstrated in combination with surgical treatment. They are of doubtful efficacy in conservative treatment regimens, at least in relation to pain.

Parenteral nutrition is at best of limited use in the treatment of symptomatic pseudocysts. In addition, it is not a low-risk therapy; potentially severe complications should be taken into consideration.

Surgical Procedures

The objective of surgical treatment has been defined for decades. It consists of avoiding the various complications by removing necrotic and infected material and through drainage and lavage of existing cavities. The first successful treatment of a pancreatic pseudocyst by excision was performed in 1882 by Bozeman.35 The first external drainage by marsupialization was described the following year by Gussenbauer,36 a method that was still being practiced in recent times. Resection is now avoided. The objectives are to relieve cystic cavities and to carry out gentle (manual) removal of easily mobilized necrotic tissue. Cystic processes are opened and either drained externally or into the stomach (the first pseudocystogastrostomy was carried out in 1921 by Jedlica37

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Objectives of Treatment

Objectives of Treatment Spontaneous Course

Spontaneous Course Conservative Treatment

Conservative Treatment Interventional Treatment

Interventional Treatment