Part 2 Gastrointestinal Imaging

Case 31

Key Imaging Finding

Esophageal mass.

Top Three Differential Diagnoses

Aberrant right subclavian artery. A left aortic arch with an aberrant right subclavian artery is the most common anomaly of the aortic arch. It is considered an incomplete vascular ring. In 80% of cases, the subclavian artery passes from the left to the right, posterior to the esophagus. It causes symptoms in only 10% of patients (dysphagia lusoria) and is usually identified incidentally on an esophagram.

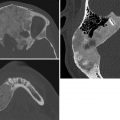

Esophageal duplication cyst. Esophageal duplications are usually on the right in the distal esophagus, in the posterior mediastinum. Most are asymptomatic, but patients may have respiratory distress or dysphagia, and if there is gastric mucosa in the wall a cyst may bleed. Duplications are rarely complete, and they rarely communicate with the esophagus. Esophageal duplications are the second most common bowel duplication, after the distal ileum. Like bowel duplications elsewhere, they result from abnormal bowel canalization. Cysts in the esophagus may be isolated or occur along with other bronchopulmonary foregut anomalies. Duplication cysts are near water attenuation on CT and show no central enhancement. On MRI, they are bright on T2 and variable on T1, depending on whether they contain proteinaceous or hemorrhagic fluid.

Other foregut cysts. Neurenteric cysts are formed by CSF-filled leptomeninges protruding through a vertebral defect. These cysts therefore occur in conjunction with vertebral anomalies, such as dysraphism, hemivertebrae, butterfly vertebrae, and split spinal cord malformation. They are most common in the lower cervical and thoracic regions. MRI assesses whether they connect to the thecal sac. Bronchogenic cysts are caused by abnormal budding of the bronchial tree. They are lined with respiratory epithelium and filled with fluid or mucinous material. Seventy percent are located in the middle mediastinum; the rest are located in the hilum or the lung.

Additional Differential Diagnosis

Vascular ring. Double-aortic arch and right aortic arch with aberrant left subclavian artery result in a filling defect in the posterior wall of the esophagus at the level of the aortic arch. Esophagrams demonstrate a posterior indentation on the esophagus on lateral and oblique views and bilateral compression on the frontal view. A double aortic arch is more common than a right arch with an aberrant left subclavian artery.

Diagnosis

Esophageal duplication cyst.

Pearls

Esophageal duplication cysts may be isolated or occur in conjunction with bronchopulmonary foregut malformations.

The esophagus is the second most common location of bowel duplication cysts, after the distal ileum.

Neurenteric cysts are accompanied with vertebral anomalies.

An aberrant right subclavian artery with a left aortic arch is usually asymptomatic.

Suggested Readings

Berrocal T, Torres I, Gutiérrez J, Prieto C, del Hoyo ML, Lamas M. Congenital anomalies of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Radiographics. 1999; 19(4):855–872 Lee NK, Kim S, Jeon TY, et al. Complications of congenital and developmental abnormalities of the gastrointestinal tract in adolescents and adults: evaluation with multimodality imaging. Radiographics. 2010; 30(6):1489–1507 Rao P. Neonatal gastrointestinal imaging. Eur J Radiol. 2006; 60(2):171–186Case 32

Key Clinical Finding

Difficulty feeding.

Top Three Differential Diagnoses

Tracheoesophageal (TE) fistula/esophageal atresia (EA). EA is classified based upon the presence and location, or absence, of a TE fistula. Proximal EA with a fistula between the airway and the distal esophageal segment is the most common type. EA is often associated with additional anomalies of the gastrointestinal tract. Cardiac, renal, and vertebral anomalies (including the Vertebral anomalies, Anal atresia, Cardiac defects, TracheoEsophageal fistula, Renal anomalies, with or without Limb malformations [VACTERL] association) are associated less frequently. Evaluation includes chest radiography after advancement of a feeding catheter to the level of the atresia, along with abdomen radiography to evaluate for intestinal air. If an H-type fistula is suspected (typically in older children who cough while feeding), an esophagram is indicated, preferably with isosmolar water-soluble contrast. Esophageal webs are considered a variant of EA and may be associated with a TE fistula. On esophagrams, webs appear as thin, transverse, or oblique filling defects. In a newborn, EA is the most common cause of difficulty feeding.

Foreign body. Foreign bodies may become lodged in relatively narrow regions of the esophagus: at the level of the thoracic inlet, aortic arch, and less commonly the gastroesophageal (GE) junction. Esophagrams may be useful when a nonopaque foreign body is suspected. Disk batteries should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a disk-shaped metallic foreign body and constitute a medical emergency due to their corrosive properties.

Esophageal duplication cyst. Esophageal duplications generally manifest as cysts, usually on the right and in the posterior mediastinum. They are rarely complete, and they rarely communicate with the esophagus. Duplication cysts are near water attenuation on CT and show no central enhancement. On MRI, they are bright on T2 and variable on T1, depending on their contents.

Additional Differential Diagnosis

Vascular ring. The most common vascular anomalies to cause dysphagia are complete vascular rings: (1) double aortic arch and (2) right aortic arch with aberrant left subclavian artery and ligamentum arteriosum arising from the descending aorta. Esophagrams demonstrate a posterior indentation on the esophagus on lateral and oblique views and bilateral compression on frontal views. The double aortic arch is more common than the right arch with aberrant left subclavian artery. A left aortic arch with an aberrant right subclavian artery is the most common anomaly of the aortic arch, but this is an incomplete vascular ring and thus rarely symptomatic.

Diagnosis

Esophageal atresia with tracheoesophageal fistula.

Pearls

Esophageal atresia is classified based upon the presence and location, or absence, of a tracheoesophageal fistula.

Proximal esophageal atresia with a fistula between the airway and the distal esophagus is most common.

Foreign bodies typically become lodged at the thoracic inlet, aortic arch, and (less often) gastroesophageal junction.

Complete vascular rings may cause esophageal compression and dysphagia.

Suggested Readings

Berrocal T, Torres I, Gutiérrez J, Prieto C, del Hoyo ML, Lamas M. Congenital anomalies of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Radiographics. 1999; 19(4):855–872 Lee NK, Kim S, Jeon TY, et al. Complications of congenital and developmental abnormalities of the gastrointestinal tract in adolescents and adults: evaluation with multimodality imaging. Radiographics. 2010; 30(6):1489–1507 Rao P. Neonatal gastrointestinal imaging. Eur J Radiol. 2006; 60(2):171–186Case 33

Key Imaging Finding

Esophageal stricture.

Top Three Differential Diagnoses

Stricture at site of repaired esophageal atresia. Approximately one-third of patients with esophageal atresia will develop an anastomotic stricture at the site of repair, regardless of whether a tracheoesophageal fistula was also present. The strictures are caused by tension on the anastomosis, a postoperative leak, and/or gastroesophageal reflux (GER). These strictures are difficult to prevent and are usually treated successfully with progressive esophageal dilatation and possible stenting. Refractory strictures are treated with esophageal anastomosis. In the immediate postoperative period, edema may cause reversible esophageal narrowing that is not considered a stricture.

Stricture due to ingestion of caustic material. Accidental ingestion of caustic materials is most common in children around age 2 years. Household items with pH of 2 or less, or 12 or more, may cause serious esophageal injury. Most ingested caustics are alkaline, with dishwashing soap and disinfectants being the most commonly ingested materials. Patients are treated with antibiotics and steroids. Grade II esophageal burns have a 50% chance of resulting in stricture formation.

Stricture secondary to GER. Chronic GER may lead to similar complications in children as in adults, including stricture formation in those with especially severe disease. It may contribute to reactive airway disease, sinusitis, and sleep apnea. A common finding on upper gastrointestinal (UGI) examinations, clinically significant GER is usually treated with protein pump inhibitors in children. Refractory cases may proceed to fundoplication, with variable success.

Additional Differential Diagnoses

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EE). This is a chronic, relapsing, immune-mediated disease characterized by eosinophilic infiltration of the esophageal wall. The incidence is increasing, and EE is now a common cause of GI symptoms in both children and adults. Symptoms are nonspecific in infants and toddlers, including failure to thrive, fussiness, and feeding intolerance, whereas older children and adolescents present with dysphagia that is worse with solid foods. Esophageal rings, strictures, and furrows may develop.

Congenital esophageal stenosis. This rare condition results from congenital malformation of the architecture of the esophageal wall. Up to one-third of patients also have esophageal atresia, other intestinal malformations, or cardiac anomalies. The disorder results from fibromuscular thickening of the wall, tracheobronchial remnants, or a membranous web (in decreasing order of frequency). Dilatation is sometimes successful, especially with fibromuscular thickening.

Diagnosis

Esophageal stricture secondary to remote ingestion of lye.

Pearls

Ingestion of caustic alkaline material such as dishwashing soap may cause esophageal stricture.

Approximately one-third of patients with esophageal atresia develop stricture at the site of repair.

Eosinophilic esophagitis in infants and toddlers has nonspecific symptoms, including failure to thrive.

Congenital esophageal stenosis may coexist with esophageal atresia.

Suggested Readings

Amae S, Nio M, Kamiyama T, et al. Clinical characteristics and management of congenital esophageal stenosis: a report on 14 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2003; 38(4):565–570 Baird R, Laberge JM, Lévesque D. Anastomotic stricture after esophageal atresia repair: a critical review of recent literature. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2013; 23(3):204–213 Dellon ES. Eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2013; 42(1):133–153Case 34

Key Imaging Finding

Externalized bowel in a newborn.

Top Three Differential Diagnoses

Omphalocele. This congenital midline abdominal wall defect forms at the base of the umbilical cord insertion and includes the umbilicus. Gut and sometimes other organs herniate into a sac that is formed by peritoneum and amnion. There are associated cardiac anomalies in 50% of patients. The kidneys are relatively cephalad and may be found just below the diaphragm. Bowel is malrotated. Approximately 30% of patients with omphalocele are born prematurely, and the disorder is slightly more common in males. Chromosomal abnormalities are present in 50% of patients. Omphaloceles are more common in patients with Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome, pentalogy of Cantrell, bladder/cloacal exstrophy, and trisomy 21. Omphalocele is often diagnosed with prenatal US. Postnatal abdomen radiographs show a large soft-tissue mass protruding from the abdomen, and gas-filled bowel loops may be seen within it. The defect is usually larger than with gastroschisis, but if the omphalocele has a narrow neck, obstruction may lead to bowel dilatation as elsewhere?. Maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) may be elevated. This condition has a high mortality rate due to associated anomalies.

Gastroschisis. Gastroschisis consists of a congenital paraumbilical defect in the ventral abdominal wall, almost always just to the right of midline. It is probably caused by environmental factors that may also cause ischemia, and it is therefore associated with intestinal atresias. Bowel loops and occasionally portions of the stomach and/or liver herniate into the defect, which is typically only 2 to 3 cm wide. The herniated structures are not covered by peritoneum. Chronic exposure to amniotic fluid damages bowel wall and may lead to impaired peristalsis and sometimes eventual short gut if bowel resection becomes necessary. Bowel is usually malrotated. The kidneys may be more cephalad than normal. As with omphalocele, the diagnosis is often made in utero with US. Abdomen radiographs show a protruding mass consisting of soft tissue or gas-filled tubular structures. Gastroschisis may be confused with an omphalocele whose membrane has torn. However, a normal umbilicus is located to the left of the mass, the key differentiating point. Maternal serum AFP is usually elevated.

Pentalogy of Cantrell. This extremely rare congenital anomaly consists of the association of five main features: anterior diaphragm deficiency, defect in the midline supraumbilical wall, defect in the diaphragmatic pericardium, defect in the lower sternum, and a variety of congenital cardiac malformations. Eventration of the heart results in “ectopia cordis.” Pentalogy of Cantrell results from abnormal mesoderm migration during the third week of gestation. Most cases are sporadic.

Diagnosis

Omphalocele.

Pearls

Both omphalocele and gastroschisis consist of herniation of bowel loops from the abdomen.

The herniated structures are usually covered by peritoneum in omphalocele (unless the membrane has ruptured) but never in gastroschisis.

The umbilicus is normal with gastroschisis, positioned just to the left of the abdominal wall defect; with omphalocele, bowel herniates into the umbilicus.

Environmental factors probably cause gastroschisis, leading to an association with bowel atresia, whereas genetic factors probably cause omphalocele.

Suggested Readings

Kelly KB, Ponsky TA. Pediatric abdominal wall defects. Surg Clin North Am. 2013; 93(5):1255–1267 Mallula KK, Sosnowski C, Awad S. Spectrum of Cantrell’s pentalogy: case series from a single tertiary care center and review of the literature. Pediatr Cardiol. 2013; 34(7):1703–1710Case 35

Key Imaging Finding

“Double bubble” sign.

Top Three Differential Diagnoses

Malrotation/midgut volvulus. Midgut volvulus is a surgical emergency that occurs when bowel twists around a narrow mesenteric pedicle in the setting of malrotation. When the diagnosis is suspected, expedited workup is mandatory to minimize morbidity and mortality. The classic presentation is bilious emesis in an infant in the first month of life, with partial duodenal obstruction. However, both clinical presentation and radiographic findings vary, and the radiographic appearance of volvulus ranges from normal to complete duodenal obstruction, mimicking duodenal atresia. An upper gastrointestinal examination is needed to establish the course of the duodenum and proximal small bowel. With malrotation, the duodenal–jejunal junction (ligament of Treitz) fails to cross to the left of midline and/or is located inferior to the pylorus. With volvulus, the proximal bowel demonstrates a “corkscrew” appearance.

Duodenal atresia/stenosis. Both duodenal atresia and duodenal stenosis result from failure of recanalization of the duodenum, either partial (stenosis) or complete (atresia). The classic radiographic presentation is the “double bubble” sign. In patients with complete atresia, there is usually no gas distal to the dilated duodenum. Patients present with vomiting in the first few hours of life. In 80% of patients, emesis is bilious, but if the obstruction is proximal to the ampulla of Vater, it is nonbilious. The degree of duodenal dilatation is usually marked, implying long-standing obstruction. Incidence of associated abnormalities is increased, and 30% of patients have trisomy 21. Duodenal stenosis may present in older patients.

Annular pancreas. Annular pancreas often coexists with duodenal atresia or stenosis. Annular pancreas may present in infants with duodenal obstruction or in older children/adults with chronic nausea and vomiting. Cross-sectional imaging shows a soft-tissue mass contiguous with the pancreas, encircling the duodenum. Upper GI examination typically shows circumferential narrowing of the second portion of the duodenum.

Additional Differential Diagnoses

Duodenal web. Intraluminal duodenal webs cause a variable degree of obstruction, and thus patients may present as older children and even adults. With severe obstruction in an infant, however, the radiographic appearance resembles other causes of duodenal obstruction. Upper GI examination may show circumferential narrowing of the duodenum or a variable-sized aperture, allowing a restricted amount of contrast material to pass distally. The web may stretch, leading to a “windsock” appearance.

Preduodenal portal vein. A preduodenal portal vein is a rare anomaly that may obstruct the duodenum. It is usually accompanied by malrotation, duodenal atresia, and other anomalies.

Diagnosis

Duodenal atresia.

Pearls

Malrotation with midgut volvulus is a surgical emergency requiring immediate diagnosis and intervention.

An upper GI examination establishes the course of the duodenum and position of the ligament of Treitz.

Duodenal atresia classically presents with the “double bubble” sign; 30% of patients have trisomy 21.

Annular pancreas results in circumferential narrowing of the second portion of the duodenum.

Suggested Readings

Berrocal T, Lamas M, Gutieérrez J, Torres I, Prieto C, del Hoyo ML. Congenital anomalies of the small intestine, colon, and rectum. Radiographics. 1999; 19(5):1219–1236 Mortelé KJ, Rocha TC, Streeter JL, Taylor AJ. Multimodality imaging of pancreatic and biliary congenital anomalies. Radiographics. 2006; 26(3):715–731 Rao P. Neonatal gastrointestinal imaging. Eur J Radiol. 2006; 60(2):171–186 Strouse PJ. Disorders of intestinal rotation and fixation (“malrotation”). Pediatr Radiol. 2004; 34(11):837–851Case 36

Clinical Presentation

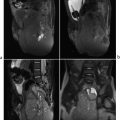

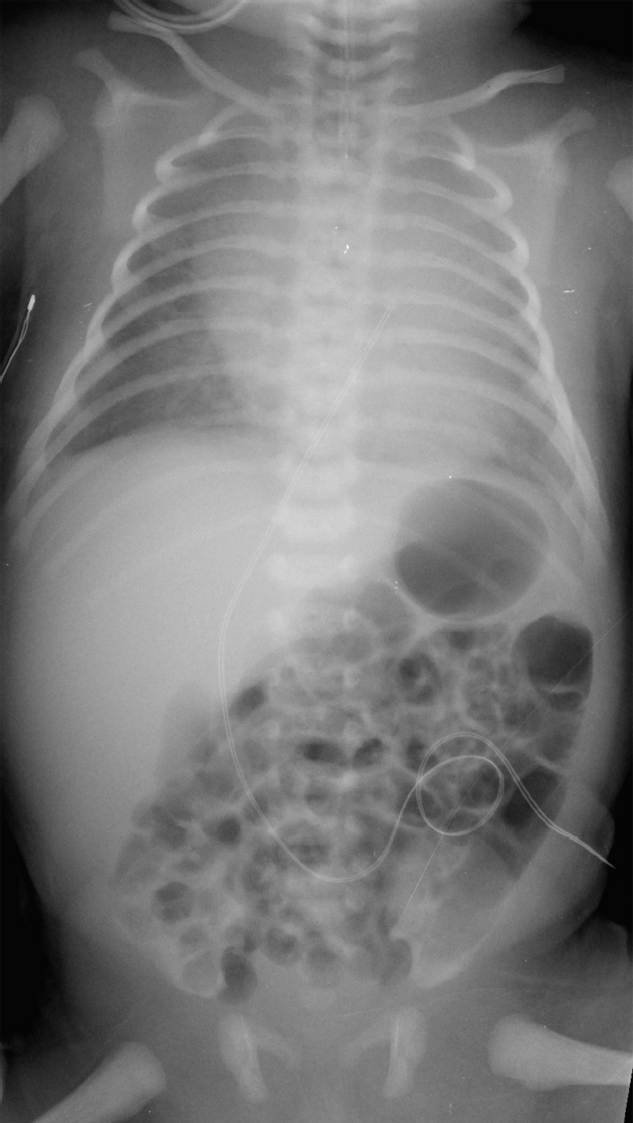

A 3-day-old African-American full-term boy with sudden onset of abdominal distension (▶Fig. 36.1).

Key Imaging Finding

Pneumoperitoneum.

Top Three Differential Diagnoses

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC). NEC is the most common surgical emergency in premature infants. Risk factors include prematurity, congenital heart disease, and perinatal asphyxia. NEC usually develops by day 10 of life. Symptoms are nonspecific and include poor feeding, abdominal distention, bloody stool, respiratory distress, and sepsis. Abdomen X-rays are the mainstay of diagnosis. Findings include bowel wall thickening, fixed/dilated bowel loops, pneumatosis, portal venous gas, and pneumoperitoneum. Findings of free air on supine images include lucency over the liver, gas outlining the falciform ligament, and gas on both sides of the bowel wall (Rigler sign). NEC is treated with bowel rest, oxygen, and antibiotics, with surgery usually performed in patients whose imaging suggests severe bowel ischemia or perforation.

Spontaneous intestinal perforation (SIP). SIP usually affects the terminal ileum. Risk factors include prematurity with extremely low birth weight and exposure to glucocorticoids or indomethacin. Perforation usually occurs within the first 10 days of life. Infants present with acute onset of abdominal distention and hypotension. Abdomen X-rays show pneumoperitoneum without pneumatosis or portal venous gas.

Spontaneous gastric perforation. Spontaneous gastric perforation usually occurs at day 2 to 7 of life in term infants. It is more common in boys and African-Americans. Risk factors include premature rupture of membranes, breech delivery, diabetic mother, low birth weight, and indomethacin treatment. Patients present with sudden onset of abdominal distention. Radiographs usually show massive pneumoperitoneum.

Additional Differential Diagnoses

Trauma. Approximately 5% of patients admitted with major trauma suffer small bowel injuries, which may be partial or full thickness. The jejunum near the duodenojejunal junction is usually affected. The distal ileum is the second most common area. Most children have had blunt trauma and demonstrate lap-belt ecchymosis. Clinical symptoms may be minimal, and CT is critical for diagnosis. Free air is evident in, at most, 50% of patients. Focal bowel wall thickening and intense enhancement, focal dilatation, and/or a moderate to large amount of free fluid may be seen. Occasionally, bowel wall discontinuity will be apparent.

Pneumomediastinum. Free air from pneumomediastinum can dissect into the abdomen, resulting in pneumoperitoneum. Mechanical ventilation is the most common cause. The mechanism is not entirely understood. Potential pathways for air entering the peritoneum include direct passage through pleural and diaphragmatic defects, microperforations in the diaphragm, and passage via the mediastinum along perivascular bundles to the retroperitoneum and finally to the peritoneum.

Diagnosis

Spontaneous gastric perforation in a patient who also has bilateral dislocated hips.

Pearls

Bowel wall thickening and fixed/dilated bowel loops suggest necrotizing enterocolitis; pneumatosis and portal venous gas are diagnostic.

Spontaneous perforation affects the ileum more often than the stomach.

Free air is seen in the minority of patients with traumatic bowel perforation; focal bowel wall thickening/enhancement, bowel dilatation, and/or free fluid are more typical.

Suggested Readings

Epelman M, Daneman A, Navarro OM, et al. Necrotizing enterocolitis: review of state-of-the-art imaging findings with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2007; 27(2):285–305 Levine MS, Scheiner JD, Rubesin SE, Laufer I, Herlinger H. Diagnosis of pneumoperitoneum on supine abdominal radiographs. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991; 156(4):731–735 Sivit CJ. Imaging children with abdominal trauma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009; 192(5):1179–1189Case 37

Key Imaging Finding

Abdominal calcifications in an infant.

Top Three Differential Diagnoses

Adrenal hemorrhage (AH). AH initially appears complex and echogenic. As the clot liquefies, the center becomes hypoechoic, and eventually the entire lesion becomes cystic. US shows involution over the course of several months. Curvilinear calcification may develop in the wall as early as 2 weeks post hemorrhage, becoming progressively more prominent. The calcifications eventually contract and appear clumped. AH is the most common adrenal mass in newborns. Seventy percent of cases occur on the right. Neonatal stress, hypoxia, septicemia, and hemorrhagic disorders may precipitate AH. The normal neonatal adrenal gland has a typical “sandwich” appearance at US, with hypoechoic cortex and a thin, echogenic medulla.

Meconium peritonitis. Meconium peritonitis develops after in utero bowel perforation due to atresia, meconium ileus, or other obstruction. Chemical peritonitis leads to ascites and multiple intra-abdominal and intrascrotal calcifications. If a pseudocyst forms, the calcifications appear clustered and, if within the cyst wall, curvilinear. In the absence of pseudocyst formation, they are scattered in the abdomen.

Retroperitoneal teratoma (RPT). RPTs typically occur near the upper pole of the left kidney. They are the third most common retroperitoneal tumor in children, after neuroblastoma and Wilms. Only 5% of pediatric teratomas occur in this location. About half are diagnosed before age 10 years, usually in girls younger than 6 months. Developing from pluripotent cells, they have a low incidence of malignancy. Most RPTs are mature, and of these most are cystic. Almost all contain fat, with foci of (often toothlike) calcification in about half of the cases. Immature RPTs are much less common and tend to be solid. Malignant degeneration is rare and often heralded by elevated serum alpha-fetoprotein.

Additional Differential Diagnoses

Neuroblastoma (NB). In the neonatal period, NB and AH may be confused, since both may appear cystic and both may calcify. However, the calcifications of AH are curvilinear, whereas those of NB are typically more stippled in appearance. Since NB in this age group is relatively indolent, it is generally possible to let follow-up US establish the diagnosis. AH shrinks on serial US, whereas NB does not. Urinary vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) is increased with NB.

TORSCH infection. Cytomegalovirus and toxoplasmosis may lead to calcifications in the liver, spleen, and peritoneum.

Fetus in fetu. This benign monozygotic twin fragment is incorporated into the body of its host twin around week 3 of gestation. Usually retroperitoneal in location, it has been reported in the cerebral ventricles, liver, pelvis, and elsewhere. The presence of limbs and vertebral bodies allow differentiation from teratoma.

Diagnosis

Meconium peritonitis secondary to jejunal and ileal atresia.

Pearls

Adrenal hemorrhage is most common on the right and may develop calcifications in the wall by age 2 weeks.

Neuroblastoma and adrenal hemorrhage may appear similar but are differentiated by follow-up US and urinary vanillylmandelic acid levels.

Meconium peritonitis follows in utero bowel perforation and may be localized (pseudocyst) or diffuse.

Retroperitoneal teratomas are most common near the left kidney’s upper pole and are usually cystic, with fat and calcification.

Suggested Readings

Lakhoo K. Neonatal teratomas. Early Hum Dev. 2010; 86(10):643–647 Rajiah P, Sinha R, Cuevas C, Dubinsky TJ, Bush WH Jr, Kolokythas O. Imaging of uncommon retroperitoneal masses. Radiographics. 2011; 31(4):949–976 Veyrac C, Baud C, Prodhomme O, Saguintaah M, Couture A. US assessment of neonatal bowel (necrotizing enterocolitis excluded). Pediatr Radiol. 2012; 42 Suppl 1:S107–S114Case 38

Clinical Presentation

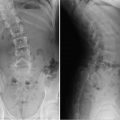

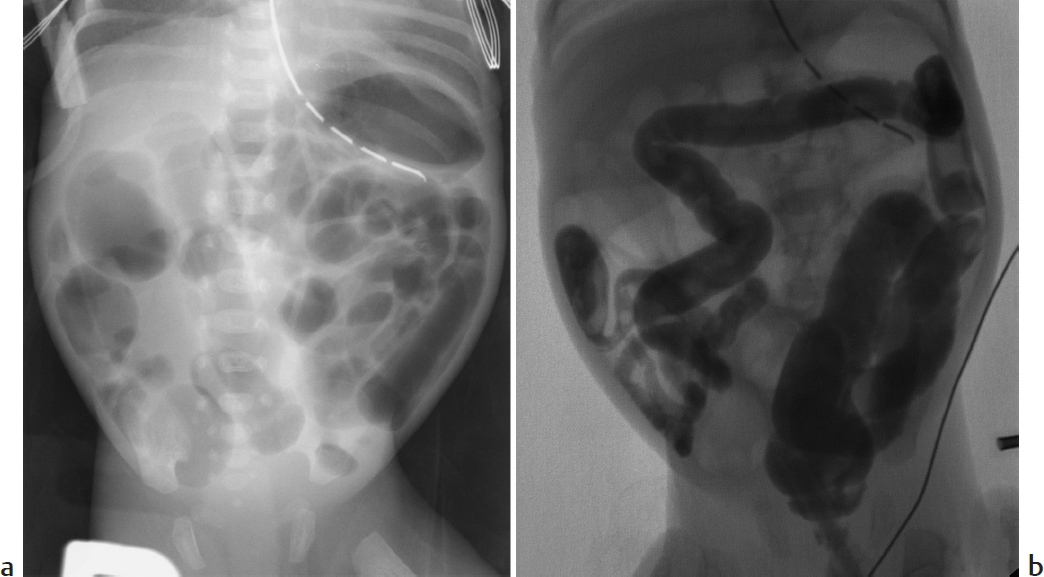

A newborn with abdominal distension and bilious residuals after feeding who has not passed meconium at 26 hours of age (▶Fig. 38.1).

Key Imaging Finding

Distal bowel obstruction in a neonate.

Top Three Differential Diagnoses

Functional immaturity of the colon. Functional immaturity includes small left colon and meconium plug syndrome. This common cause of low bowel obstruction is associated with prematurity, infants whose mothers received magnesium sulfate or opiates during labor, and infants of diabetic mothers. Infants present with failure to pass meconium, abdominal distension, and/or vomiting. Radiographs show diffuse bowel distension. Contrast enema defines a normal rectum and meconium plug(s) in the rectosigmoid colon. The left colon may be small in caliber to the splenic flexure. No organic obstruction is seen. The stooling pattern becomes normal after the contrast enema stimulates passage of meconium.

Meconium ileus. Meconium ileus may be the first sign of cystic fibrosis. Tenacious meconium in the terminal ileum and right colon results in distal bowel obstruction. Radiographs may show a lack of fluid-fluid levels, as well as a soap-bubble appearance in the right lower quadrant. A contrast enema defines meconium pellets in the distal ileum and right colon, as well as the smallest of microcolons. Diagnostic water-soluble enema may also be therapeutic, facilitating passage of meconium pellets.

Ileal atresia/stenosis. Ileal atresia/stenosis probably results from focal intrauterine ischemic injury. Neonates present with low bowel obstruction. Contrast enema is helpful in defining microcolon, which results from colonic nonuse. This may be accompanied with jejunal or colonic atresia and stenosis.

Additional Differential Diagnoses

Hirschsprung disease (HD). HD results from failure of complete craniocaudal migration of intramural ganglion cells. The aganglionic segment cannot relax, resulting in distal bowel obstruction. Symptoms include constipation, abdominal distension, and/or bilious vomiting. About 2% of patients with trisomy 21 have HD. Radiographs show distal bowel obstruction. A transition zone between the spastic, narrow distal colon and the dilated more proximal colon is defined at contrast enema, usually in the rectosigmoid region. Patients with HD have an abnormal rectosigmoid ratio, which should be at least 1—with the rectum always at least as large as the sigmoid. Rarely HD affects the entire colon, which then resembles a “lead pipe.” Suction biopsy confirms absence of ganglion cells below the transition zone.

Anal atresia/anorectal malformations. Anal atresia is an important cause of low bowel obstruction in infants. It is usually clinically evident. It is important to evaluate for associated renal and spinal cord anomalies in these babies. Fistulas commonly extend to the urethra (males) or vagina (females).

Diagnosis

Meconium ileus.

Pearls

Functional immaturity of the colon is associated with prematurity and infants of diabetic mothers.

Hirschsprung disease is due to aganglionosis; the transition point is usually in the rectosigmoid region.

Ileal atresia is thought to result from intrauterine ischemia; there is microcolon due to nonuse.

Meconium ileus occurs in patients with cystic fibrosis and shows extreme microcolon with meconium pellets in the ileum.

Suggested Readings

Berrocal T, Lamas M, Gutieérrez J, Torres I, Prieto C, del Hoyo ML. Congenital anomalies of the small intestine, colon, and rectum. Radiographics. 1999; 19(5):1219–1236 Rao P. Neonatal gastrointestinal imaging. Eur J Radiol. 2006; 60(2):171–186 Vinocur DN, Lee EY, Eisenberg RL. Neonatal intestinal obstruction. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012; 198(1):W1-W10Case 39

Clinical Presentation

A 9-year-old boy with abdominal pain after falling forward onto the handlebars of his bicycle (▶Fig. 39.1).

Key Imaging Finding

Duodenal mass.

Top Three Differential Diagnoses

Duodenal hematoma. This injury classically results from blunt abdominal trauma sustained in the course of motor vehicle or bike handlebar accidents; it also occurs with nonaccidental trauma and rarely complicates endoscopy. Injuries are commonly present elsewhere. Patients complain of pain and may develop obstruction of the gastric outlet or of the pancreatic/biliary tree. CT shows bowel wall thickening and a mural hematoma, and commonly both free and retroperitoneal fluid. It helps establish whether there is perforation as well, in which case there may be retroperitoneal air and/or extravasation of oral contrast. Treatment is usually supportive, and the hematoma eventually resolves. Perforation mandates prompt surgical repair.

Duodenal duplication cyst. Although bowel duplication cysts most often involve the distal ileum, the duodenum may be affected. Patients present with a mass, obstruction, or—in the 20% in whom gastric mucosa is present—hemorrhage. Cysts are usually spherical or tubular and adjacent to bowel, sometimes communicating with it. US shows the “gut signature” of echogenic mucosa, hypoechoic muscularis, and echogenic serosa. CT/MRI show mild enhancement of the wall, but the central portion does not enhance.

Lymphadenopathy. Porta hepatis lymph nodes extend along the portal vein to the hepatoduodenal ligament and may simulate a duodenal mass. Lymphadenopathy is common with cirrhosis. Bulky nodes suggest lymphoma, but periportal node involvement is common only with extensive intra-abdominal disease. Infections such as tuberculosis and hepatitis B/C may lead to less striking periportal lymphadenopathy.

Additional Differential Diagnosis

Hepatic tumor. A liver tumor that arises in the caudate lobe or near the porta hepatis may mimic a duodenal mass. If hemorrhagic, it may resemble a large, complex duodenal hematoma. Depending on patient age, the diagnosis of hepatoblastoma (5 years old or younger) or hepatocellular carcinoma (older than 5 years) would be likely. Serum alpha-fetoprotein is usually elevated.

Diagnosis

Duodenal hematoma.

Pearls

Duodenal hematoma results from blunt trauma and appears as bowel wall thickening or a mural mass.

Duodenal duplication cysts are spherical or tubular and demonstrate the US “gut signature.”

Bulky lymphadenopathy in the porta hepatis suggests lymphoma.

Liver tumors that affect the caudate lobe may simulate a duodenal mass.

Suggested Readings

Berrocal T, Torres I, Gutiérrez J, Prieto C, del Hoyo ML, Lamas M. Congenital anomalies of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Radiographics. 1999; 19(4):855–872 Helmberger TK, Ros PR, Mergo PJ, Tomczak R, Reiser MF. Pediatric liver neoplasms: a radiologic-pathologic correlation. Eur Radiol. 1999; 9(7):1339–1347 Shilyansky J, Pearl RH, Kreller M, Sena LM, Babyn PS. Diagnosis and management of duodenal injuries in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1997; 32(6):880–886Case 40

Key Imaging Finding

Cyst adjacent to bowel wall.

Top Three Differential Diagnoses

Bowel duplication cyst. Bowel duplication cysts most often involve the distal ileum, with the duodenum, stomach, esophagus, and other areas affected in decreasing order of frequency. Patients present with a mass, obstruction, or—in the 20% in whom gastric mucosa is present—hemorrhage. Cysts are usually spherical and do not communicate with bowel; occasionally, they are tubular. US shows the “gut signature” of echogenic mucosa, hypoechoic muscularis, and echogenic serosa. There may be intraluminal debris, especially likely if the cyst communicates with adjacent bowel. CT and MRI show mild enhancement of the wall, whereas the central material does not enhance.

Meckel diverticulum. Meckel diverticulum is the most common GI congenital anomaly and is usually asymptomatic. It is found in 2% of patients and usually pre sents by age 2 years. Most Meckel diverticula are 2 inches long and originate from the antimesenteric side of the ileum, within 2 feet of the ileocecal valve. Children may present with bloody stool and bowel obstruction secondary to torsion, or small bowel intussusception with the diverticulum acting as a lead point. Symptoms may mimic appendicitis. Occasionally, a Meckel diverticulum may be diagnosed incidentally on CT or MRI as a small cystic structure. US diagnosis is difficult, since the size and location of the diverticulum vary. CT more accurately defines the location, size, and associated complications. Meckel diverticulum is most often diagnosed on technetium-99m Meckel scan.

Lymphatic malformation. Lymphatic malformations are part of a spectrum of congenital vascular malformations, which includes mesenteric and omental cysts. Lymphatic malformations have an endothelial lining and thin wall of smooth muscle; they contain lymphatic spaces and lymphoid tissue. Usually multilocular, they are diffuse, crossing anatomical spaces. The lesions occur in small or large bowel mesentery and may be massive, up to 40 cm. They are often found in asymptomatic adults, but one-third are diagnosed in children younger than 15 years, who may present with pain, mass, vomiting, or fever. If complicated by hemorrhage or infection, the normally anechoic fluid becomes complex, and calcifications may develop. Multiple septations are usually present. MRI offers optimal delineation of lesion extent. Mesenteric cysts, unlike lymphatic malformations, are lined with columnar or cuboid epithelium and lack smooth muscle in their walls. Sixty percent are found in the small bowel mesentery, and they may extend into the retroperitoneum. Omental cysts are the least common. They are confined to the greater or lesser omentum.

Additional Differential Diagnosis

CSFoma (cerebrospinal fluid pseudocyst). Loculated CSF may collect around the peritoneal end of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt, resulting in a cystic mass, shunt failure, and hydrocephalus. This is usually due to adhesions. If the distal end of the shunt does not change position on serial imaging, adhesions should be suspected.

Diagnosis

Jejunal duplication cyst.

Pearls

Bowel duplication cysts are most common at the distal ileum and have a classic gut signature on US.

Meckel diverticulum may present with torsion or small bowel intussusception and may mimic appendicitis.

Lymphatic malformations are usually multilocular and cross anatomical spaces.

Mesenteric cysts occur in the small bowel mesentery and may extend into the retroperitoneum.

Suggested Readings

Ranganath SH, Lee EY, Eisenberg RL. Focal cystic abdominal masses in pediatric patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012; 199(1):W1–W16 Rao P. Neonatal gastrointestinal imaging. Eur J Radiol. 2006; 60(2):171–186 Wootton-Gorges SL, Thomas KB, Harned RK, Wu SR, Stein-Wexler R, Strain JD. Giant cystic abdominal masses in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2005; 35(12):1277–1288Case 41

Key Imaging Finding

Bowel obstruction.

Top Three Differential Diagnoses

Perforated appendicitis. Acute appendicitis is the most common cause of surgical abdomen in children. Diagnosis may be challenging, since presentation may mimic other gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and gynecologic disorders, potentially delaying diagnosis and increasing the likelihood of perforation. Bowel distention may either be due to adynamic ileus from peritonitis or due to inflammation and adhesive bands in the right lower quadrant causing mechanical obstruction. US or CT may identify the abnormal appendix. Perforation is suggested if there are focal defects in the mucosa or an adjacent phlegmon/abscess.

Intussusception. Intussusception is the most common cause of bowel obstruction in children less than 5 years of age. Although radiographs are useful to diagnose obstruction, US is the imaging modality of choice to establish the diagnosis of intussusception. The “target sign” of alternating bowel wall layers of the internal intussusceptum and external intussuscipiens is readily apparent on US. Initial management is by fluoroscopic or US-guided enema reduction, successful in about 90% of cases.

Meckel diverticulitis. Children with Meckel diverticulitis may present with bloody stool and bowel obstruction secondary to torsion or small bowel intussusception (the diverticulum may act as a lead point). US diagnosis is difficult, since diverticulum size and location vary. If the diverticulum has perforated, both clinical signs and US findings may mimic appendicitis. CT more accurately defines location, size, and complications. Confirmatory nuclear medicine Meckel scan is sometimes useful for equivocal cases.

Additional Differential Diagnoses

Adhesions. If the patient has had previous abdominal surgery, postoperative adhesions are often the primary diagnostic consideration. Upper GI examination with small bowel follow-through or CT often allows identification of the transition zone and determination of whether the obstruction is partial or complete.

Incarcerated inguinal hernia. Bowel may herniate through the inguinal region if there is a patent processus vaginalis (very common in newborns and present in about 20% of 2-year-olds). The presence of a gas-containing bowel loop in the scrotum or inguinal canal is diagnostic. However, in the setting of obstruction, bowel often contains no gas, and the diagnosis may be suggested by thickening of the inguinal fold. US demonstrates bowel in and beyond the inguinal canal.

Malrotation with volvulus. Ongoing volvulus in the setting of malrotation may cause bowel obstruction.

Diagnosis

Perforated appendicitis.

Pearls

Perforated appendicitis may cause adynamic ileus or obstruction due to distal bowel inflammation.

Intussusception is the most common cause of bowel obstruction in children less than 5 years of age and is readily diagnosed with US.

Meckel diverticulum may present with obstruction, mimicking appendicitis.

Adhesive bands are a common cause of bowel obstruction after abdominal surgery.

Suggested Readings

Hryhorczuk A, Lee EY, Eisenberg RL. Bowel obstructions in older children. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013; 201(1):W1–W8 Nolan T, Abramson L, Sanchez TR. Multimodality imaging of perforated appendicitis in children. Contemporary Diagnostic Radiology. 2012; 35:1–6 Sivit CJ. Imaging the child with right lower quadrant pain and suspected appendicitis: current concepts. Pediatr Radiol. 2004; 34(6):447–453Case 42

Clinical Presentation

A 12-year-old neutropenic girl with fever, diarrhea, and a history of acute myelocytic leukemia, status post bone marrow transplant (▶Fig. 42.1).

Key Imaging Finding

Bowel wall thickening in an immunocompromised child.

Top Three Differential Diagnoses

Pseudomembranous colitis. Pseudomembranous colitis results from overgrowth of Clostridium difficile and usually occurs in patients receiving antibiotics. The colonic wall is markedly thickened secondary to mucosal and submucosal edema that results in central hypodensity. The disease usually affects the entire colon, but occasionally only the right colon is involved. The “accordion sign” results from intraluminal fluid extending between pseudomembranes and edematous haustra. Pericolonic fat is relatively spared.

Neutropenic colitis/typhlitis. This inflammatory and necrotizing colitis occurs in neutropenic children and typically involves the right colon. However, it may be limited to the cecum or include the terminal ileum. Most common in those with acute leukemia, it presents with fever, diarrhea, and tenderness. The classic appearance is circumferential, symmetrical mural thickening that enhances heterogeneously. Pericolonic inflammatory stranding is common, and intramural pneumatosis may occur. Contrast enema is contraindicated due to perforation risk. Perforation and sepsis result in the high mortality rate of 40 to 50% in patients treated medically.

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). GVHD occurs when marrow T-lymphocytes damage recipient epithelial cells. Older children are at increased risk. Patients typically present with diarrhea, hepatomegaly, ascites, and resultant abdominal distension. Mucosal ulceration and destruction occur, followed by replacement of mucosa with vascular granulation tissue. This results in the typical CT appearance of intense mucosal enhancement along with dilatation affecting the entire small and large bowel. On small bowel follow-through, the contrast-filled bowel has a “ribbonlike” appearance. Treatment consists of increased immunosuppression, and outcome is usually good.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree