Part 5 Head and Neck Imaging

Case 131

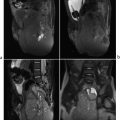

Key Imaging Finding

Intraocular mass.

Top Three Differential Diagnoses

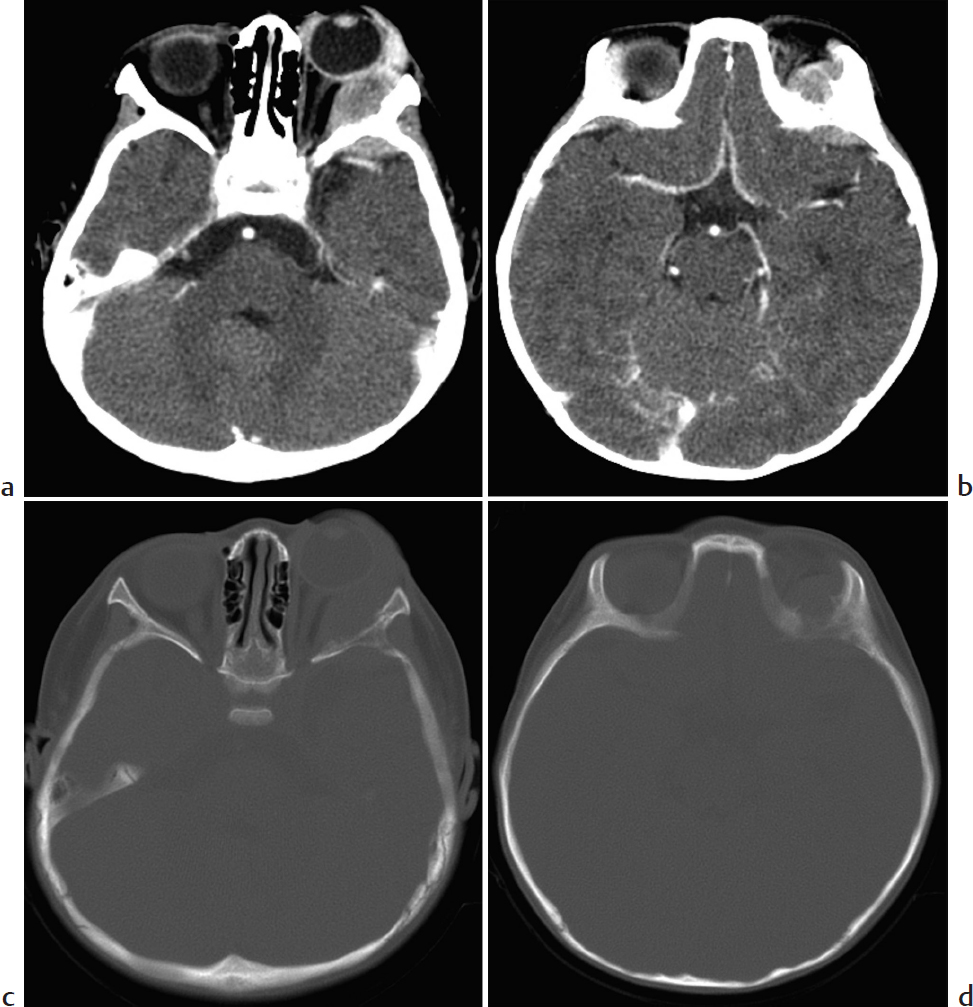

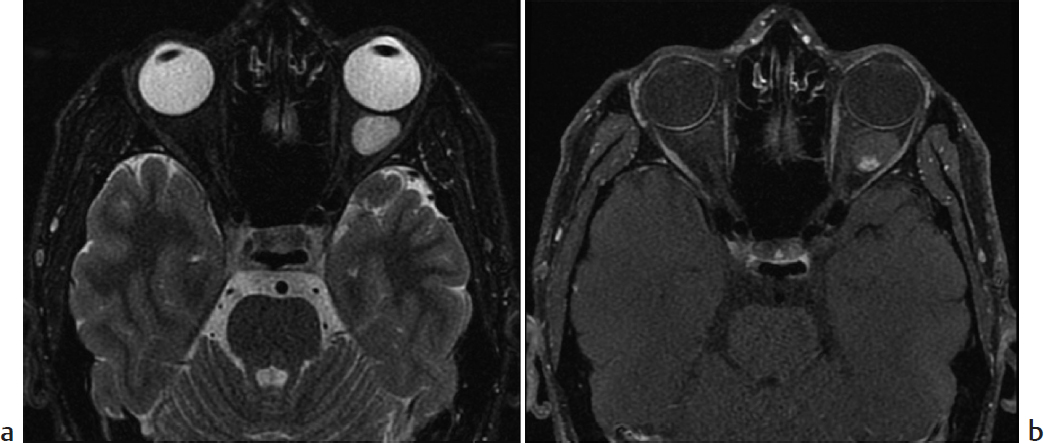

Retinoblastoma. This is the most common intraocular malignancy in children. Most cases are diagnosed by age 5 years. The tumor is often sporadic. Inherited disease is more likely to be bilateral and to have additional suprasellar and pineal tumors. Patients usually present with leukocoria (white reflex), strabismus, or occasionally vision loss. Calcification is a near-constant feature, important to diagnosis. On MRI, the tumor is slightly hyperintense on T1 and hypointense on T2; it enhances avidly. It is important to evaluate the intra- and extraocular extent, as well as additional CNS disease. Metastases may involve regional lymph nodes, lung, liver, and bones.

Persistent fetal vasculature (PFV; formerly persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous). PFV is a congenital condition that occurs when the primary vitreous (mesenchymal tissue that occupies the posterior chamber of the orbit) fails to regress and instead proliferates, forming fibrofatty tissue. Typically unilateral, PFV presents with leukocoria and microphthalmia and is usually diagnosed soon after birth. On CT, the orbit is small, with hyperdense vitreous that is typically hyperintense on T1 and T2. The hyperdense material assumes a V shape due to retinal detachment, a central remnant hyaloid stalk, and a retrolental mass.

Coats disease. This retinal telangiectasia leads to breakdown of the blood–retina barrier and accumulation of fat and fluid in the retina and subretinal space. Patients present with leukocoria, progressive vision loss, and eventual retinal detachment, usually around age 6 to 8 years. CT and MRI show a noncalcified intraocular lesion that does not enhance. The lesion is denser than vitreous on CT and hyperintense on T1 and T2.

Additional Differential Diagnosis

Retinopathy of prematurity. Also known as retrolental fibroplasia, this vascular disorder of the retina is usually seen in premature infants weighing less than 1.5 kg who received oxygen therapy. Vascular scarring and retinal detachment develop. Imaging shows an abnormal retrolental density, retinal detachment—sometimes with a fluid–fluid level, and micropthalmia. Calcification is rare except in advanced disease.

Diagnosis

Retinoblastoma.

Pearls

Retinoblastoma usually calcifies and shows avid enhancement on MRI.

Persistent fetal vasculature is characterized by micropthalmos with V-shaped vitreous that is hyperdense on CT and hyperintense on both T1- and T2-W MRI.

Coat disease also has hyperdense vitreous that like persistent fetal vasculature is T1/T2 hyperintense, but without a central stalk.

Suggested Readings

Burns NS, Iyer RS, Robinson AJ, Chapman T. Diagnostic imaging of fetal and pediatric orbital abnormalities. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013; 201(6):W797–W808 Chung EM, Specht CS, Schroeder JW. From the archives of the AFIP: pediatric orbit tumors and tumorlike lesions: neuroepithelial lesions of the ocular globe and optic nerve. Radiographics. 2007; 27(4):1159–1186 Rauschecker AM, Patel CV, Yeom KW, et al. High-resolution MR imaging of the orbit in patients with retinoblastoma. Radiographics. 2012; 32(5):1307–1326Case 132

Key Imaging Finding

Cystic lesion in the anteromedial orbit.

Top Three Differential Diagnoses

Dacryocystocele. A dacryocystocele is a benign, usually congenital cystic mass that forms at the inferomedial canthus due to obstruction of the proximal and distal ends of the nasolacrimal duct. Patients typically present with a triad of imaging findings, including a medial canthal mass, an enlarged nasolacrimal duct, and an intranasal mass. CT shows a cystic mass at the medial canthus and nasal cavity with mostly homogeneous fluid attenuation. On MRI, a dacryocystocele appears as a high-T2 cystic lesion in the medial canthal region extending into the nasal cavity, where it displaces the inferior turbinate and nasal septum. Internal debris may result in heterogeneous signal characteristics. There may be thin peripheral enhancement.

Dacryocystitis. Dacryocystitis is inflammation of the nasolacrimal duct sac along the medial canthus and is typically a clinical diagnosis. It sometimes complicates dacryocystocele. Imaging, if performed, demonstrates a round mass in the medial canthus with peripheral rim enhancement. If untreated, dacryocystitis may progress to abscess or orbital cellulitis.

Dermoid/epidermoid. Dermoid and epidermoid cysts of the orbit are common congenital orbital lesions in children. Both are developmental, resulting from either incomplete separation of ectoderm from the neural tube or complex ectodermal in-folding during facial development. Both appear as wellcircumscribed, cystic masses with smooth remodeling of adjacent bone. MRI characteristics vary, since epidermoids contain fluid, whereas dermoids contain lipid. Epidermoids demonstrate low T1 and high T2 signal intensity (similar to CSF but without suppression of signal on FLAIR). They have increased signal on DWI. Dermoid cysts in contrast are hypodense on CT and hyperintense on T1-W MRI.

Additional Differential Diagnoses

Encephalocele. A naso-orbital encephalocele is a congenital neural tube defect with herniation of cranial contents through a defect in the midline anterior skull base. On MRI, it appears as a heterogeneous mass contiguous with intracranial structures. Signal characteristics are similar to those of brain and CSF.

Abscess. An orbital abscess may result from untreated or progressive periorbital cellulitis. CT and MRI show heterogeneous attenuation and signal characteristics within the orbit, with peripheral enhancement and restricted diffusion. A distinct fluid collection may be observed.

Diagnosis

Dacryocystocele.

Pearls

Dacryocystocele results from obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct and appears as a cystic medial canthal mass.

Dacryocystitis is inflammation of the nasolacrimal duct sac and may complicate a dacryocystocele.

Since dermoids are lipid, they resemble fat on MRI, whereas epidermoids resemble simple fluid.

Suggested Readings

LeBedis CA, Sakai O. Nontraumatic orbital conditions: diagnosis with CT and MR imaging in the emergent setting. Radiographics. 2008; 28(6):1741–1753 Lowe LH, Booth TN, Joglar JM, Rollins NK. Midface anomalies in children. Radiographics. 2000; 20(4):907–922, quiz 1106–1107, 1112Case 133

Key Imaging Finding

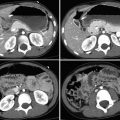

Solid extraconal orbital mass.

Top Three Differential Diagnoses

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS). RMS is the most common extraocular orbital malignancy in children. About 10% of RMS occurs in the orbit (superomedial or inferior). This soft-tissue tumor is aggressive, growing rapidly and usually presenting with proptosis. Most RMS is extraconal, though there may be intraconal extension. Bony erosion and invasion of the paranasal sinuses are fairly common. Homogeneous on CT, the tumor enhances diffusely. It appears more heterogeneous on MRI, especially if it has bled. RMS encases or displaces—but does not enlarge—the ocular muscles. The eyelid may be thickened without being infiltrated by tumor. Metastases (lung and bone) are less common than with RMS elsewhere.

Neuroblastoma (NB) metastasis. Most pediatric orbital metastatic disease is NB, bilateral in about half of patients. Orbital NB is usually associated with an abdominal primary and is most common in patients younger than 2 years. Lytic lesions are often present elsewhere. Proptosis and periorbital ecchymosis result in the “raccoon eye” appearance. The tumor usually arises from the bony roof or lateral orbital wall and is extraconal. Preseptal extension is uncommon. There is permeative bone destruction, aggressive periosteal reaction, and often scattered intratumoral calcification. NB is hyperdense on unenhanced CT. Hemorrhage and/or necrosis lead to a heterogeneous appearance on T2-W MRI, along with heterogeneous enhancement. Dural metastases may cause dural widening. Urine vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) is often elevated.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH). The superior or superolateral orbit is a relatively common site of eosinophilic granuloma (another name for the individual lesion in LCH). LCH usually develops before age 4 years. Identification of disease in the orbit should prompt a search for skeletal involvement elsewhere (technetium-99m bone scan, radiographs, and/or whole-body MRI). LCH is usually osteolytic, and beveled margins are typical of skull lesions. CT and MRI show a mass that destroys bone and may extend into the orbit, temporal fossa, face, and epidural region. Enhancement is moderate to marked. The mass is intermediate on T1 and usually hyperintense or occasionally hypointense on T2. It may be bilateral. Patients may present with diabetes insipidus (DI), which indicates pituitary involvement.

Additional Differential Diagnosis

Granulocytic sarcoma (GS, chloroma). This soft-tissue tumor may precede systemic disease in patients with acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), develop during the course of disease, or be the first sign of relapse. Most GS occurs in children younger than 10 years. GS is usually unilateral. Orbital GS typically originates in the subperiosteal lateral orbital wall and does not erode bone. It encases rather than invades adjacent structures, such as the lacrimal gland and extraocular muscles. GS is homogeneous and does not calcify. It enhances uniformly. Iso- or hypointense compared with muscle on T1, it is heterogeneously iso- to hyperintense on T2.

Diagnosis

Neuroblastoma metastasis.

Pearls

Orbital rhabdomyosarcoma is most common in the superomedial or inferior orbit and invades bone and sinuses.

Neuroblastoma metastasis is most common in the superior or lateral orbit wall and shows bone destruction.

Granulocytic sarcoma may precede development of AML, is lateral within the orbit, and does not erode bone.

Bilateral extraocular intraorbital masses are most likely neuroblastoma, granulocytic sarcoma, or Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

Suggested Readings

Chung EM, Smirniotopoulos JG, Specht CS, Schroeder JW, Cube R. From the archives of the AFIP: pediatric orbit tumors and tumorlike lesions: nonosseous lesions of the extraocular orbit. Radiographics. 2007; 27(6):1777–1799 Chung EM, Murphey MD, Specht CS, Cube R, Smirniotopoulos JG. From the archives of the AFIP. Pediatric orbit tumors and tumorlike lesions: osseous lesions of the orbit. Radiographics. 2008; 28(4):1193–1214Case 134

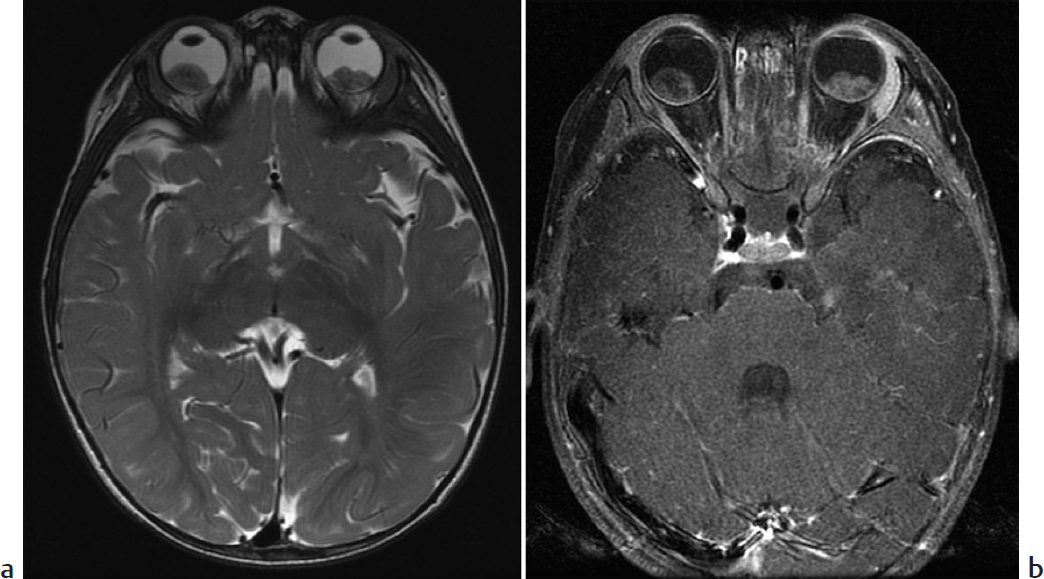

Key Imaging Finding

Hypervascular intraconal mass.

Top Three Differential Diagnoses

Hemangioma. Capillary hemangiomas are one of the most common vascular lesions of the orbit in children. They develop shortly after birth and undergo a proliferative phase that lasts up to 1 year, followed by an involutional phase. CT shows a lobulated soft-tissue mass that enhances intensely, most often found in the extraconal space. On MRI, the lesion appears well circumscribed, isointense to hyperintense on T1, and moderately hyperintense on T2 (relative to muscle). Enhancement is intense. Flow voids and thin internal septa may be seen. Orbital capillary hemangiomas may occur in the setting of PHACES (posterior fossa malformations, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, cardiac defects, eye abnormalities, sternal cleft, and supraumbilical raphe) syndrome. Maffucci syndrome is characterized by multiple enchondromas and soft-tissue hemangiomas that may involve the orbit.

Venolymphatic malformation (VLM). VLM is composed of variable amounts of lymphatic and venous vessels. Although a fairly common vascular lesion of the orbit, it is relatively rare in children. VLM appears as a poorly circumscribed, irregular, lobulated intraorbital mass that often involves both the intra- and extraconal spaces. Lesions may have small, cystic areas. CT may show bony remodeling and calcified phleboliths. MRI is preferred, typically demonstrating fluid–fluid levels that are isointense to slightly hyperintense on T1 and hyperintense on T2 (relative to brain). Enhancement on CT and MRI varies but is typically less intense than with orbital hemangiomas.

Dermoid/epidermoid. These lesions may occur in the deep as well as anterior orbit and should be considered in the setting of a pediatric orbital mass. Epidermoids demonstrate low T1 and high T2 signal intensity (similar to CSF, but without suppression of signal on FLAIR). They have increased signal on diffusion. Dermoid cysts in contrast are hypodense on CT and hyperintense on T1-W MRI.

Additional Differential Diagnosis

Optic nerve glioma. Optic nerve gliomas are uncommon tumors of the orbit, typically seen in the setting of neurofibromatosis type 1. CT and MRI show fusiform enlargement of the optic nerve. The lesion may be T1 isointense to hypointense and T2 hyperintense (compared to the contralateral optic nerve). Enhancement is common.

Diagnosis

Hemangioma.

Pearls

Hemangiomas of the orbit are vascular lesions that demonstrate intense contrast enhancement.

Optic nerve gliomas demonstrate fusiform enlargement of the optic nerve and usually occur in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1.

Venolymphatic malformations of the orbit are less common in children than in adults and appear as a variably enhancing lobulated mass that may have phleboliths or fluid–fluid levels.

Suggested Readings

Chung EM, Smirniotopoulos JG, Specht CS, Schroeder JW, Cube R. From the archives of the AFIP: pediatric orbit tumors and tumorlike lesions: nonosseous lesions of the extraocular orbit. Radiographics. 2007; 27(6):1777–1799 Smoker WR, Gentry LR, Yee NK, Reede DL, Nerad JA. Vascular lesions of the orbit: more than meets the eye. Radiographics. 2008; 28(1):185–204, quiz 325Case 135

Key Imaging Finding

Soft-tissue mass in the middle ear.

Top Three Differential Diagnoses

Otitis media. Acute otitis media is typically a disease of infancy and early childhood. It does not require imaging if uncomplicated. CT/MRI show fluid and debris within the middle ear and mastoid air cells, sometimes with air fluid levels. Bony structures are preserved, including the middle ear ossicular chain, mastoid trabeculae, and overlying cortex. Chronic otitis media due to underlying eustachian tube dysfunction may be complicated by granulation tissue formation and development of an acquired cholesteatoma.

Congenital cholesteatoma. Cholesteatomas are classified as congenital or acquired, with the congenital form typically presenting in children. Congenital cholesteatomas arise from the embryonic inclusion of epithelial rest cells within the temporal bone and are therefore composed primarily of tissue derived from epithelium, such as keratin and cholesterol. They may occur anywhere within the temporal bone, including the middle ear. CT demonstrates an expansile soft-tissue mass. MRI shows a well-marginated lesion that may erode the ossicles and scutum. It is dark on T1 and usually brighter than CSF on T2. Lesions do not typically attenuate on FLAIR. There is no central enhancement, although some lesions may demonstrate thin peripheral enhancement.

Aberrant internal carotid artery (ICA). An aberrant ICA is a collateral pathway of the normal ICA, resulting from involution of the first embryonic portion of the ICA. The reduced caliber ICA consequently passes through the tympanic canal into the middle ear, returning to its normal course in the petrous carotid canal. The normal bone that should cover the carotid canal is absent. CT and MRI show a soft-tissue mass continuous with the ICA. MRI shows signal flow void, and postcontrast images demonstrate avid arterial enhancement. Middle ear surgery performed on an unrecognized aberrant ICA can be catastrophic.

Diagnosis

Congenital cholesteatoma.

Pearls

Acute otitis media demonstrates soft-tissue opacification of the middle ear and mastoids, without bony erosion.

A congenital cholesteatoma appears as a soft-tissue mass that causes bony erosion, typically in the setting of conductive hearing loss.

It is important to evaluate for continuity with the ICA in order to exclude aberrant ICA.

Suggested Readings

Baráth K, Huber AM, Stämpfli P, Varga Z, Kollias S. Neuroradiology of cholesteatomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011; 32(2):221–229 Juliano AF, Ginat DT, Moonis G. Imaging review of the temporal bone: part I. Anatomy and inflammatory and neoplastic processes. Radiology. 2013; 269(1):17–33Case 136

Key Imaging Finding

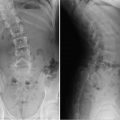

Inner ear congenital malformation.

Top Three Differential Diagnoses

Enlarged vestibular aqueduct (VA). Enlarged VA is by far the most common cause of sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL). Hearing loss is often progressive and may be exacerbated by trauma. In addition, enlarged VA accompanies inner ear anomalies in almost 85% of patients. The condition is often bilateral. On CT, the upper normal for the midpoint of the VA is 1.5 mm. MRI demonstrates enlargement of the endolymphatic duct and sac.

Incomplete partition type 2 (IP2; Mondini malformation). SNHL due to this and the following malformations is usually diagnosed in infancy. Temporal bone MRI and CT play complementary roles. Brain MRI is useful for diagnosing frequently coexistent brain abnormalities. With IP2, the modiolus is incomplete, and there is no interscalar septum or osseous spiral lamina. The cochlea makes only 1.5 turns. The basal turn is normal, but the middle and apical turns fuse to form an apical cyst. In addition, the VA is often enlarged, whereas the semicircular canals tend to be normal.

Common cavity. With common cavity, there is no differentiation between the cochlea and vestibule, so they form a confluent cystic cavity that completely lacks internal architecture. The cavity is usually wider than it is tall. The semicircular canals are usually also deformed.

Additional Differential Diagnoses

Cochlear hypoplasia. In this condition, a small cochlear bud (1–3 mm) protrudes from a usually normal vestibule. It completes at most one turn. The internal auditory canal (IAC) is usually small, and the vestibule and semicircular canals are usually abnormal.

Incomplete partition type 1 (IP1; cystic cochleovestibular malformation). With IP1, there is no modiolus, so the cochlea appears cystic. Unlike with common cavity, the dilated vestibule is separate from the cochlea. Axial imaging shows a circle-of-8 or snowman appearance. The VA is normal and the IAC dilated, increasing risk of meningitis.

Diagnosis

Incomplete partition type 2 (Mondini malformation).

Pearls

Enlarged vestibular aqueduct is the most common cause of sensorineural hearing loss, and in addition this condition accompanies many inner ear anomalies.

With incomplete partition type 2, the modiolus is incomplete; the middle and apical turns of the cochlea fuse to form an apical cyst.

With incomplete partition type 1, the dilated vestibule is separate from the cochlea, but with common cavity they form a confluent cystic cavity.

A tiny cochlear bud protrudes from the vestibule in cochlear hypoplasia.

Suggested Readings

DeMarcantonio M, Choo DI. Radiographic evaluation of children with hearing loss. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2015; 48(6):913–932 Joshi VM, Navlekar SK, Kishore GR, Reddy KJ, Kumar EC. CT and MR imaging of the inner ear and brain in children with congenital sensorineural hearing loss. Radiographics. 2012; 32(3):683–698 Sennaroglu L, Saatci I. A new classification for cochleovestibular malformations. Laryngoscope. 2002; 112(12):2230–2241Case 137

Key Imaging Finding

Narrowed choanae (posterior nasal passage).

Top Three Differential Diagnoses

Choanal atresia/stenosis. Bilateral choanal atresia is the most common cause of neonatal nasal obstruction, but if unilateral this may present in older children. It occurs when the posterior part of the nasal passage is congenitally stenotic or occluded, blocking air passage to the posterior nasopharynx and oropharynx. The choana is normally about 3 mm wide in children younger than 2 years. Atresia is osseous (90%) or membranous (10%) and is unilateral in about half of cases. Since infants are obligate nasal breathers, affected neonates typically show signs of respiratory distress or even cyanosis at birth. Crying relieves respiratory distress by opening the oral airway. Rhinorrhea and the inability to pass a nasal cannula are other important clinical signs that should initiate investigation. Bilateral choanal atresia is a life-threatening condition, and an oral airway must be established immediately. The condition is best diagnosed on CT, where soft tissue or bone bridges the posterior nasal passage on one or both sides.

Nasal aperture stenosis. The nasal (pyriform) aperture is the bony inlet of the nose, formed by the nasal and maxillary bones. The maxillary spine marks its inferior border. Stenosis of the aperture is a very rare cause of nasal obstruction in infants. It is typically associated with other severe congenital midline anomalies, such as holoprosencephaly. There is no standardized size for the aperture, so diagnosis can be difficult. Findings on CT include inward bowing of the maxillary spine and bone or soft tissue extending across the nostrils just inside the nares.

Stenosis of entire nasal airway. This is usually osseous and may be associated with prematurity. It is also seen in Apert syndrome (maxillary hypoplasia). This extremely rare condition may be asymptomatic in the newborn period, as stenosis may be incomplete.

Additional Differential Diagnosis

Congenital nasal mass. Congenital masses in the midline nasal region resulting from defective neural tube closure include anterior encephaloceles, nasal gliomas, and dermoids/epidermoids. These can result in nasal obstruction. MRI and CT demonstrate a cystic or soft-tissue mass in the nasal passageway.

Diagnosis

Unilateral choanal atresia.

Pearls

Choanal atresia can be bony or soft tissue.

Bilateral choanal atresia presents in neonates with respiratory distress as well as constant nasal drainage (rhinorrhea) and inability to pass a nasal cannula.

The diagnosis of unilateral choanal atresia may be delayed because the infant is able to use one nostril to breathe.

Choanal atresia is much more common than nasal aperture stenosis or stenosis of the entire airway.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree