9 Topography of the Head–Neck Region

The head–neck region may be described as the region between the head and neck. From a systematic view point, the pharynx is considered part of the neck. In clinical practice, lesions of the nasal cavity spread easily into the nasopharynx or vice versa. Anatomically and pathologically the oral cavity is closely related to the oropharynx. The topography of the pharynx will first be elaborated upon in this chapter, particularly in the clinical context of its relationships with the nasal and oral cavities. The region of the craniocervical junction extending from the postero-inferior surface of the base of the skull (level of the mastoid processes to the external occipital protuberance), down to the first two cervical vertebrae and the attached muscles332 will be described thereafter.

9.1 Pharynx and Parapharyngeal Space

9.1.1 Topography of the Pharynx

The pharynx is a 12- to 15-cm-long fibromuscular tube extending from the base of the skull to the commencement of the esophagus at the level of the cricoid cartilage. It lies anterior to the cervical spine and extends up to the VIth cervical vertebra. Flexion and extension of the cervical spine can alter the cross-sectional appearance of the pharynx. In the coronal series, the posterior wall of the pharynx is imaged in a coronal plane (see ▶Fig. 3.7c and 3.7d); while in the sagittal series, it runs obliquely to the coronal plane (see ▶Fig. 4.2a and ▶Fig. 4.2b).

Unlike the closed posterior wall, the anterior wall exhibits three openings for the passage of air and food. The pharynx is thus divided into:

Nasopharynx: This proximal part (previously: epipharynx) communicates with the nasal cavities through the choanae.

Oropharynx: This middle part (previously: mesopharynx) communicates with the oral cavity through the isthmus of fauces.

Laryngopharynx: The distal part of the pharynx from where the aditus laryngis continues into the larynx.

Median and paramedian sections are best suited for evaluation of the nasopharynx and the oropharynx, which also enable optimal delineation of the retropharyngeal space.

The nasopharynx (see ▶Fig. 3.6a, ▶Fig. 3.6b, ▶Fig. 3.7c, ▶Fig. 3.7d, ▶Fig. 4.2a, and ▶Fig. 4.2b) is functionally similar to the nasal cavity with a similar mucus membrane and a multilayered ciliated epithelium. The roof of the nasopharynx forms the outer aspect of the base of the skull, between the pharyngeal tubercle of the occipital bone, the apex of the temporal bone, and a small part of the inferior surface of the sphenoid. The unpaired pharyngeal tonsil lies on the posterior wall of the nasopharynx. ▶Fig. 4.2a demonstrates an atrophic pharyngeal tonsil of a 70-year-old man. The pharyngeal opening of the pharyngotympanic tube (Eustachian tube) is present on the lateral wall of the nasopharynx along the posterior prolongation of the inferior nasal concha. The superior and posterior edges of this opening are elevated by the cartilaginous part of the tube. The levator veli palatini produces an elevation of the mucous membrane at the lower margin of the tubal opening. Lymphoreticular connective tissue, the tubal tonsil, is present within the mucosa of the tubal orifice. This forms part of pharyngeal lymphoid tissue, which if pathologically enlarged may interfere with ventilation of the tympanic cavity.

The oropharynx (see ▶Fig. 3.7c, ▶Fig. 4.2a, ▶Fig. 4.2b, and ▶Fig. 4.3a) is the space behind the root of the tongue, the paired palatopharyngeal arches, and the uvula. Radiologists594 define the oropharynx as the part of the pharynx extending from the level of the hard palate to the hyoid bone.

The most inferior part of the pharynx, the laryngopharynx, begins opposite the laryngeal opening and extends downward up to the entrance to the esophagus. The posterior wall of the larynx bulges into the lumen of the pharynx.

9.1.2 Muscles of the Pharyngeal Wall

The muscles of the pharyngeal wall comprise:

Constrictors of the pharynx

Slender elevators of the pharynx, namely the palatopharyngeus and the stylopharyngeus

The topography of these thin muscles of the pharyngeal wall can best be understood by comparison of coronal and sagittal series (see ▶Fig. 7.37 and ▶Fig. 7.38).

The superior, middle, and inferior constrictors of the pharynx arise from the skull, the hyoid bone, and the larynx and their fibers run posteriorly and upward to meet in the midline raphe on the posterior wall of the pharynx. Contraction of the pharyngeal constrictors pulls the hyoid bone and the larynx upwards simultaneously. The superior constrictor bulges into the pharyngeal lumen (Passavant’s ridge), which provides resistance against the soft palate closing off the nasal cavity. The phayngeal constrictor is innervated by the glossopharyngeal (N. IX) and vagus (N. X) nerves.

The pharyngeal elevators contract and elevate the walls of the pharynx and the larynx and insert into the larynx. They are supplied by the glossopharyngeal (N. IX) nerve.

9.1.3 Vessels of the Pharyngeal Wall

The ascending pharyngeal artery supplies the wall of the pharynx and forms numerous anastomoses with branches from the superior and inferior thyroid and lingual arteries.

Venous drainage takes place through the pharyngeal plexus, which lies posterior to the constrictors of the pharynx.

Lymphatics from the pharyngeal wall run via retropharyngeal lymph nodes to deep cervical lymph nodes.

9.1.4 Nerves of the Pharyngeal Wall

Afferent and efferent innervation of the pharyngeal wall is provided by the glossopharyngeal (N. IX) and vagus (N. X) nerves and the sympathetic trunk. They are pathways of vital reflexes such as the swallowing and the protective reflexes. Afferent and efferent pathways of the swallowing reflex are coordinated in the swallowing center of the medulla oblongata.

9.1.5 Parapharyngeal Space

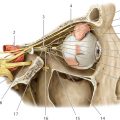

The parapharyngeal (lateral pharyngeal) space lies in the transitional zone between head and neck, lateral and posterolateral to the pharynx. Laterally this space is bounded by the lateral and medial pterygoids and the fascial capsule of the parotid gland, while medially it extends up to the pharyngeal wall. Its cranial boundary is marked by the triangular area at the base of the skull, which contains the openings for the internal carotid arteries, the jugular foramen, and the hypoglossal canal. Caudally it extends into the connective tissue layer of the carotid triangle. The styloid process with the stylopharyngeus, styloglossus, and stylohyoid project cranially into the parapharyngeal space, dividing it into anterior and posterior compartments.

The anterior compartment contains fat through which run small vessels including the ascending pharyngeal artery (see ▶Fig. 9.1).

All of the following course through the posterior compartment: the internal carotid artery (see ▶Fig. 3.8c, ▶Fig. 3.8d, ▶Fig. 4.5c, and ▶Fig. 4.5d), the internal jugular vein (see ▶Fig. 3.9c, ▶Fig. 3.9d, ▶Fig. 4.6c, and ▶Fig. 4.6d), the glossopharyngeal nerve (see ▶Fig. 3.9a and ▶Fig. 4.5a), the vagus nerve (see ▶Fig. 3.8a and ▶Fig. 4.5a), the accessory nerve (see ▶Fig. 3.9a and ▶Fig. 4.5a), and the hypoglossal nerve (see ▶Fig. 3.9a and ▶Fig. 4.5a).

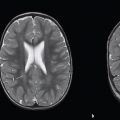

Division into spaces is presently based on the layers of cervical fascia and the pathways through which disease processes may spread and the probability of their occurrence (see ▶Fig. 5.2a). Abbreviations used conform to their generally acknowledged English names (e.g., BS = buccal space). The parapharyngeal space is easily identified on coronal sections and is usually bilaterally symmetrical, with any departure from this symmetry suggesting a space-occupying lesion. This space is identified on T1-weighted MR images by contained fatty tissue between the muscles of mastication and the constrictors of the pharynx.594 The retropharyngeal space is the cleft between the posterior wall of the pharynx and the deep cervical fascia, the prevertebral layer anterior to the cervical vertebrae.

9.2 Craniocervical Junction

The craniocervical junction includes the postero-inferior part of the base of the skull extending from the level of the external occipital protuberance (see ▶Fig. 4.2c, ▶Fig. 4.2d, ▶Fig. 4.8, ▶Fig. 5.1b, ▶Fig. 5.6a, and ▶Fig. 5.6b) to the pharyngeal tubercle (see ▶Fig. 4.2c, ▶Fig. 4.2d, and ▶Fig. 4.8) of the occipital bone, the first two cervical vertebrae (see ▶Fig. 3.1b) and the attached muscles. Laterally the region extends to the mastoid processes (see ▶Fig. 3.1b, ▶Fig. 3.10c, ▶Fig. 3.10d, ▶Fig. 3.24, ▶Fig. 4.1b, ▶Fig. 4.7c, ▶Fig. 4.7d, ▶Fig. 4.13, ▶Fig. 5.1b, ▶Fig. 5.3, and ▶Fig. 5.18). The occipital bone, atlas, and axis form a functional articular unit enabling free movement in three directions. Muscles form a cone-like structure around the cranial end of the vertebral column, extending up to the skull. This muscular cone consists posteriorly and laterally of the superficial and deep neck muscles; two prevertebral muscles are present anteriorly. The individual state of contraction of the muscles in the three spatial axes can result in highly variable images of the craniocervical junction, thereby complicating the interpretation of CT and MR scans in this region. Median and paramedian slices facilitate anatomic orientation.

9.2.1 Bones of the Craniocervical Junction

Predominant bones of the craniocervical junction are:

The occipital bone is bowl-shaped, with the foramen magnum placed eccentrically (see ▶Fig. 3.1b, ▶Fig. 3.12c, ▶Fig. 3.12d, ▶Fig. 3.24, ▶Fig. 3.25, ▶Fig. 4.8, ▶Fig. 5.17, and ▶Fig. 6.3). The lambdoid suture (see ▶Fig. 4.8) extends beyond the superior boundary of the craniocervical junction, the external occipital protuberance (see ▶Fig. 4.8). The paired occipital condyles (see ▶Fig. 3.9c, ▶Fig. 3.9d, ▶Fig. 3.23, ▶Fig. 4.1, ▶Fig. 4.4d, ▶Fig. 4.9, and ▶Fig. 4.10) lie anterolateral to the foramen magnum (see ▶Fig. 3.23) and form the convex articular surface for the atlanto-occipital joint.

The nearly ring-like atlas (see ▶Fig. 3.1b and ▶Fig. 4.1b) possesses a delicate anterior arch (see ▶Fig. 3.8c, ▶Fig. 3.21, ▶Fig. 4.2c, ▶Fig. 4.2d, and ▶Fig. 4.8) and a posterior arch (see ▶Fig. 3.11c, ▶Fig. 3.25, ▶Fig. 4.2c, ▶Fig. 4.2d, ▶Fig. 4.8, and ▶Fig. 5.2), as well as two sturdy lateral masses (see ▶Fig. 3.9c, ▶Fig. 3.9d, ▶Fig. 3.10c, ▶Fig. 3.22, ▶Fig. 3.24, ▶Fig. 4.4c, ▶Fig. 4.4d, ▶Fig. 4.10, and ▶Fig. 5.2). Concave articular surfaces are present on the superior aspect of the lateral masses articulating with the condyles of the occipital bone (see ▶Fig. 3.10c, ▶Fig. 3.23, ▶Fig. 4.4c, ▶Fig. 4.4d, and ▶Fig. 4.10). The nearly flat inferior surfaces of the lateral masses articulate with the lateral atlantoaxial joints (see ▶Fig. 3.9c, ▶Fig. 3.9d, ▶Fig. 3.23, ▶Fig. 4.4c, ▶Fig. 4.4d, and ▶Fig. 4.10). The posteriorly directed inner aspect of the anterior arch (see ▶Fig. 4.8) contains a smooth facet for the median atlantoaxial joint (see ▶Fig. 4.8). The vertebral artery and its accompanying veins run in a groove on the posterior arch of the atlas (see ▶Fig. 3.10c, ▶Fig. 3.10d, and ▶Fig. 3.11c). The atlas usually stands out on coronal images as it is broader than the adjoining cervical vertebrae (see ▶Fig. 3.23).

A characteristic feature of the second cervical vertebra, the axis (see ▶Fig. 3.1b), is the peg-shaped dens (see ▶Fig. 3.1b, ▶Fig. 3.9c, ▶Fig. 3.22, ▶Fig. 4.2c, ▶Fig. 4.2d, ▶Fig. 4.8, and ▶Fig. 5.2) which projects upward into the ring of the atlas forming the axis of a pivot joint. It articulates with the facet on the inner aspect of the anterior arch of the atlas as the median atlantoaxial joint (see ▶Fig. 4.8).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree