Benign Changes

3.1.1 Histological Principles

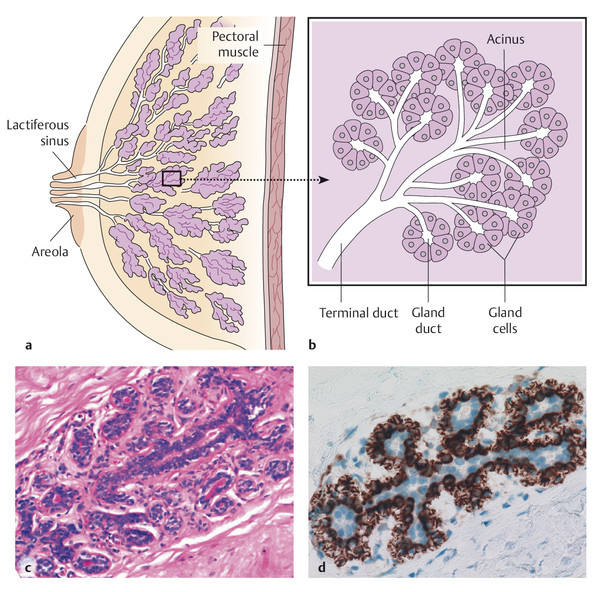

The breast is made up of 15 to 25 glands (lobules or segments) (▶ Fig. 3.1a). These glands comprise a dense system of bifurcating ducts and ductules ending in the milk-secreting lobules (acini; ▶ Fig. 3.1b). The large majority of breast diseases originate in the epithelial cells that line the ducts and lobules. The most frequent point of origin is at the ends of the glandular “tree,” the terminal duct lobular unit (TDLU) (▶ Fig. 3.1c, d).

Fig. 3.1 Anatomy of the breast. (a, b) Schematic diagrams. (c, d) histology and immunohistology. (a) Mammary gland with ca. 15 to 25 individual lobes, each ending at the nipple orifice. (b) Detail from (a): The branching ducts lead into terminal ducts (ductules) and end in the secretory lobes (acini). (c) Terminal duct lobular unit (TDLU). (d) TDLU with a luminal (blue nuclei) and a basal myoepithelial cell layer (brown represents CD10).

Immunhistochemically, the luminal cell layer (both glandular and ductal) and the basal myoepithelial cell layer develop from a progenitor cell expressing basal (high molecular weight) cytokeratins (CK5/6 or CK5/14). The mature myoepithelial cell may revert to being CK5/6 negative, though myofilaments with antibodies for smooth muscle actin (SMA) and CD10 32 can be detected. Mature luminal duct and gland cells are positive for the low molecular weight cytokeratin CK8/18, but negative for CK5/6 (progenitor cell model 1, 7).

3.1.2 Nonneoplastic, Nonproliferative Diseases of the Breast

Diseases of the breast are among the most common disorders of organs in women and are often associated with the formation of a palpable lump. In principle breast diseases can also develop in men. It is important to distinguish between palpable lumps caused by true new tissue growth (tumor or neoplasia) and those that do not exhibit uncontrolled, progressive growth (nonneoplastic, pseudotumorous). Because breast tissue is hormone-responsive, changes occur particularly during the menstrual cycle but also during pregnancy and lactation, which can sometimes promote changes such as the formation of cysts (mastopathy), or inflammatory processes (mastitis). In individual cases it can be difficult, not only clinically and in breast imaging, but also pathologically, to distinguish nonneoplastic benign changes from neoplastic malignant lesions. Indeed, a reliable evaluation of pathological findings in the breast can be a challenge even for pathologists. In the following subsections, the typically diffuse changes in breast tissue are described and distinguished from those lesions that typically lead to tumor formation.

Defects and Supernumerary Structures

Congenital abnormalities of the breast are relatively rare and are divided into defects and supernumerary structures:

Defects: These range from the complete absence of breast tissue and nipple (amastia) to isolated abnormalities of the nipple (athelia, microthelia) or the breast (amatia, aplasia) and to bilateral or unilateral underdevelopment of the breast (micromastia, anisomastia).

Supernumerary structures: Supernumerary nipples (polythelia) and/or breasts (polymastia) develop in the milk line and are found in approximately 3% of the population, with no gender preference. The most common localizations of such formations are in the axilla (45% of cases), near the breast (25%), and in the medioclavicular line of the chest wall (12%). Carcinomas in a mamma aberrata (dystopic carcinomas) are rare and are prognostically unfavorable. 40

Macromastia

The term “macromastia” (diffuse hypertrophy of the breast) refers both to premature (infantile) breast development and to excessive growth of the breast beyond what is age-appropriate. Macromastia occurs most frequently in adolescence, with proliferation of ductal epithelia and fibrosis of breast tissue being the most prominent histological features. Most commonly there is an increase in fatty tissue (lipomatous macromastia). In the differential diagnosis, the following secondary forms must be distinguished from primary macromastia:

Paraneoplastic: in the case of endocrine-active tumors (hypophyseal adenoma, small-cell bronchial carcinoma, Cushing’s disease, acromegaly, dysgerminoma).

Drug related (digitalis).

Tumor-related: by infiltration of the breast tissue (malignant lymphomas).

Fibrocystic Mastopathy

Characteristic features of a simple fibrocystic breast condition are morphological changes in which fibrosis of the mammary tissue with duct ectasia is predominant but not epithelial proliferation. Such changes can be detected in ca. 50% of women age 30 years and over and are considered by some authors to be a variant of the norm with no pathological significance. There is no associated increased risk of breast cancer. 1

Typical histological findings include the following changes:

Cysts and duct ectasia: The lactiferous ducts are noticeably enlarged but generally show an intact epithelial lining (▶ Fig. 3.2), although solitary cysts (larger than 1 cm) may form.

Fibrosis: This is an intralobular or perilobular collagen fiber proliferation in the breast stroma.

Metaplasia: This is usually an apocrine metaplasia with cylindrical, red eosin-stained epithelia (similar to sweat glands).

Fig. 3.2 Fibrocystic mastopathy. (a) Cystic duct ectasia. (b) Fibrocystic tissue transformation with ectatic ductules, partly lined by (reddish) apocrine metaplastic epithelium (A), and incipient focal lobule sclerosis (S).

(From Bock K, Ramaswamy A, Köhler H. Fortbildungskurs zur Aufrechterhaltung und Weiterentwicklung der fachlichen Befähigung für Pathologen [6.10.2012]—Referenzzentrum Mammographie Südwest am Universitätsklinikum Gießen-Marburg am Standort Marburg [Course text].)

Mastitis

Inflammations of the breast are either acute (usually bacterial infection) or mainly chronic (usually resulting from retention of secretion). Reactive specific and granulomatous inflammatory changes are rare. 2

Acute Mastitis

Acute inflammations (thelitis, areolitis) are usually caused by contact infection during breastfeeding and can lead to a canalicular transmission of the inflammation to the glandular tissue (puerperal mastitis). The most frequent pathogen (95% of cases) is Staphylococcus aureus from the nasopharyngeal cavity of the child, the mother, or the nursing staff. Purulent inflammations of the mammary gland (nonpuerperal mastitis) are rare after the postnatal period. These develop due to displacement of the lactiferous duct by nipple calluses, scars, or tumors with subsequent retention of secretions. Secondary colonization can then lead to formation of a suppurating abscess. Histologically, there is a leukocytic infiltration of the milk ducts and lobules with invasion of the mantle and supporting tissue. Healing of abscesses and fistulas can leave scarring and deformation of the breast.

Chronic Periductal Mastitis (Retention Syndrome)

About one-third of nonpuerperal mastitis cases are nonbacterial, chemically induced inflammations caused by intraductal secretion retention (▶ Fig. 3.3a). Histological features include ectatic ducts filled with thickened secretion and foam cells (galactostasis) and periductal lymphocytes and plasma cells (periductal mastitis). The ductal epithelium is usually flattened or replaced by granulation tissue. The final stage, obliterative galactophoritis, is characterized by periductal fibrosis and scarred duct obliteration. Occasionally there are granulomatous inflammatory changes, which must then be distinguished from nonpathogenic, idiopathic granulomatous mastitis (the histological features being lobulocentric, noncaseating granulomas) as well as from a pathogen-specific mastitis.

Fig. 3.3 Breast inflammation. (a) Galactophoritis obliterans with cystic ductal ectasia (Z) and wall thickening in a duct that was displaced by a papilloma (P); known as retention syndrome. (b) Fat necrosis with scarred-cystic degradation of the necrotic adipose tissue (so-called oil cysts; lower right, regular adipose cells).

Pathogen-Specific Mastitis

Pathogen-specific inflammations of the breast are rare, and include tuberculous mastitis (hematogenic), syphilis (chancre of the nipple), and the extremely rare actinomycosis, or other mycotic pseudotumors (blastomycosis, cryptococcosis). Histology typically shows an inflammatory response accompanied by central acellular (“caseating”) necrosis. Substantiation is provided by microscopic, bacteriologic, or molecular genetic pathogen verification. Sarcoidosis rarely affects the breast. Histomorphological findings of noncaseating granulomas must therefore be interpreted within the scope of the clinical picture.

Panniculitis-Associated Fat Necrosis

Necroses of the mammary adipose tissue often occur as tumorlike changes in patients between 50 and 70 years of age. In up to 50% of cases, the patient’s history includes trauma, such as postsurgical status (ca. 1 in 200 operations). Clinical findings include a circumscribed, painful lump that is difficult to distinguish from a carcinoma, even on mammography. Microscopy shows fat necrosis with a lipophagic inflammatory response (foam cells, Touton giant cells) partially displaying cystlike, confluent fat-cell necroses (oil cysts; ▶ Fig. 3.3b). Pronounced accompanying hemorrhages can occur if the patient is undergoing anticoagulant therapy. The differential diagnosis includes abscesses and carcinomas.

Inflammatory Response to Breast Implants

Foam cell–rich and scarring inflammatory changes can also occur as a reaction to a prosthesis (breast implant). This occurs in 22 to 58% of cases 3 to 9 months after implantation. In 4 to 6% of cases, implants may rupture and cause tumorlike silicone granulomas to form. These contain nonbirefringent silicone components surrounded by histiocytes and giant cells. 1

3.1.3 Benign Tumor-Forming Diseases

In the current classification of the World Health Organization (WHO), breast lesions that typically manifest as circumscribed, sometimes palpable tumors are divided into epithelial, mesenchymal, and fibroepithelial tumors; growths in nipple tissue; malignant lymphomas; metastatic tumors; and tumors of the male breast. 24 This section describes primarily the benign, noncarcinomatous lesions (▶ Table 3.1; for malignant lesions, see ▶ 3.2).

Tumor group | Entity |

Epithelial tumors | Benign epithelial proliferations |

(Sclerosing) adenoses and variants | |

Radial scar and complex sclerosing lesion | |

Adenomas of the breast | |

Intraductal proliferative lesions | |

UDH | |

Columnar cell lesions | |

FEA | |

ADH | |

Epithelial-myoepithelial tumors | |

Pleomorphic adenoma | |

Adenomyoepithelioma (with/without carcinoma) | |

Fibroepithelial tumors | Fibroadenoma |

Phyllodes tumor | |

Hamartoma | |

Mesenchymal tumors | Nodular fasciitis |

Myofibroblastoma | |

Desmoid-type fibromatosis | |

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor | |

Benign vascular lesions (hemangioma, angiomatosis) | |

Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia | |

Granular cell tumor | |

Benign peripheral nerve sheath tumor (neurofibroma, schwannoma) | |

Lipoma and angiolipoma | |

Leiomyoma | |

Tumors of the nipple | Adenoma |

Syringomatous tumor | |

Tumors of the male breast | Gynecomastia |

Abbreviations: ADH, atypical ductal hyperplasia. FEA, flat epithelial atypia. UDH, usual ductal hyperplasia. | |

Epithelial Proliferations

There are a number of distinct proliferating epithelial lesions originating in the lobules that can occasionally be difficult to distinguish from carcinomas, both radiologically and histologically. These lesions do not generally present an increased risk of breast cancer. Exceptions are the rare forms of microglandular adenosis and the complex sclerosing lesions (radial scar), which are often found in conjunction with in situ or invasive, usually lobular, carcinoma. 4

Adenosis

Adenosis is associated with a microscopically circumscribed area containing an increased number of enlarged lobules. Rarely, an adenosis may present as an adenosis tumor, a mass usually smaller than 2 cm in diameter (adenosis tumor). Some degree of nuclear atypia is sometimes seen in cases of apocrine epithelial metaplasia or pronounced cell hyperplasia (florid adenosis), as well as during pregnancy or breastfeeding. These should not be misdiagnosed as neoplastic in situ lesions. Typically, adenosis shows secretory deposits within the gland lumen in periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stains (▶ Fig. 3.4a). In contrast, secretory deposits in lobular neoplasias are intracellularly located within the cytoplasm, as seen in signet-ring cells.

Fig. 3.4 Types of adenosis. (a) Ductal adenosis (blunt duct adenosis, A) with slightly ectatic lobules lined by a single-layer cylindrical epithelium (columnar cell metaplasia) with granular (often calcified) secretion in the lumen (N, normal lobule). (b) Sclerosing adenosis with tumorlike gland proliferation and typically intact myoepithelial layer. Insert: nuclei of the gland lumen epithelia (blue), bordered by p63-positive myoepithelium (brown). (c) Radial scar with glandular and ductal proliferation radiating from a hyaline-elastotic center (☆). Peripheral adenosis. (d) Tubular carcinoma is the most important differential diagnosis. There is a comparable central elastotic fibrosis (☆). Unlike the radial scar, however, the gland here does not have an intact myoepithelial layer (cf. inserts: myoepithelial imaging with cytokeratin CK5 is positive in [c] and negative in [d]).

(Figures [c] and [d] from Bock K, Ramaswamy A, Köhler H. Fortbildungskurs zur Aufrechterhaltung und Weiterentwicklung der fachlichen Befähigung für Pathologen [6.10.2012]—Referenzzentrum Mammographie Südwest am Universitätsklinikum Gießen-Marburg am Standort Marburg [Course text].)

Sclerosing Adenosis

Sclerosing adenosis is a compact proliferation of glandular epithelium and especially myoepithelium in a lobulelike arrangement (▶ Fig. 3.4b). The basal membrane is intact and microcalcifications are commonly found within the gland lumen. Actin-sm (SMA)-positive or CK5/6-positive myoepithelium is seen between the glands and forms an important differential diagnostic criterion for the differentiation of adenosis from scirrhous and tubular carcinomas. Invasion of the nerve sheath or vessels is seen occasionally (up to 2% of cases), but should not be interpreted as a sign of malignancy.

Radial Scar

The radial scar is a special form of adenosis with central hyaline-elastotic scarring that encloses individual glands and radiates toward the periphery, where it passes into an adenosis (▶ Fig. 3.4c). Lesions larger than 0.5 cm with ductal ectasia, metaplasia, and epithelial hyperplasia are also called complex sclerosing lesions. The absence of fatty tissue invasion and the presence of primarily double-row tubules with intact epithelia and myoepithelia are generally considered to exclude carcinoma (▶ Fig. 3.4d). In case of doubt, this can be immunohistologically confirmed (CK5/6, SMA-positive).

Microglandular Adenosis

A characteristic sign of microglandular adenosis is irregular and indistinctly circumscribed groups of proliferated, relatively uniform gland tubules that are lined with cubic epithelium and, in contrast to the other forms of adenosis, show no myoepithelium (i.e., are SMA negative). An eosinophilic, PAS-positive secretion is commonly seen in the lumen. Clinically and histologically these lesions have the appearance of a tubular carcinoma. Unlike the tubular carcinoma, however, the cells of the microglandular adenosis express S100 but no hormone receptors, and are always negative for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and for GCDFP-15 (gross cystic disease fluid protein). The basal membrane around the newly formed glands is intact. 5

Adenomas of the Breast

As a rule, adenomas are circumscribed, rounded, and well-defined lumps in the breast, comprising tubular proliferations with two-layered glandular epithelium and myoepithelium (tubular adenoma or adenoma purum). These account for approximately 1% of all benign breast lesions and typically develop in young women after menarche. Radiologically they have the appearance of fibroadenomas. During pregnancy there are also signs of secretion (lactating adenoma). Furthermore, apocrine epithelial metaplasia may be present (apocrine adenoma), or polypoid adenomas may be seen bulging into ectatic ducts (ductal adenoma). A rare form of adenoma is the pleomorphic adenoma, which has a morphology comparable to that of the corresponding salivary gland tumor. It consists of epithelial and clear myoepithelial cell proliferations, mixed with chondroid components. All of these lesions are benign, show no recurrence after complete removal, and are not linked to an increased risk of cancer in any way. However, they must be distinguished from the very rare myoepithelial and epithelial-myoepithelial lesions that look similar to the tubular adenoma and may be associated with atypias. 24, 25

Intraductal Proliferative Lesions and Precursor Lesions of Invasive Breast Cancer

Intraductal epithelial cell proliferations occur in the following forms:

UDH: usual (or simple) ductal hyperplasia.

FEA: flat epithelial atypia (arising from a columnar cell lesion).

ADH: atypical ductal hyperplasia.

DCIS: ductal carcinoma in situ.

The risk of malignancy associated with these lesions depends on the degree of atypia and the extent of breast tissue involvement. The latest WHO classification no longer uses the so-called DIN terminology (ductal intraepithelial neoplasia), originally introduced by the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP), 43 for the classification of intraductal proliferating lesions.

Usual Ductal Hyperplasia

Benign proliferative lesions of the ductal epithelia without morphological signs of atypia are called “usual [or “simple”] ductal hyperplasia” (▶ Fig. 3.5a). The remarkable histopathological feature is in the terminal ducts of the TDLU, where the duct lumina are filled by epithelial proliferations more than four cell layers wide. These form irregular, usually slitlike lumina adapted to the ducts (peripheral fenestrations) with thin epithelial bridges. The cells are often arranged in lines (streaming) and are morphologically made up of different cell types, some with elongated and nonround nuclei, as well as focal apocrine metaplasia. The basal myoepithelial layer is typically intact. Unlike in DCIS, the cells in UDH predominantly express cytokeratin CK5/6 (▶ Fig. 3.5c), which is why they are also called progenitor cell lesions or stem cell lesions. 5 Women with UDH have a slightly (1.5-fold to 2-fold) increased risk of developing breast cancer.

Fig. 3.5 Intraductal proliferative lesions. (a) Usual ductal hyperplasia (UDH) with slitlike residual lumina in one duct (lower right; H) and another duct (upper left; K) with a single layer lining of cylindrical epithelium (columnar cell metaplasia; both B2 lesions). (b) Flat epithelial atypia (FEA): the gland is lined with partially overlapping epithelium with enlarged nuclei and a number of visible nucleoli; one mitosis is visible between 1 and 2 hours (B3 lesion). (c) Immunohistochemically, the UDH shows CK5/6-positive myoepithelia with mosaiclike distribution throughout the epithelia. (d) In atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH), these CK5/6-positive myoepithelia are nearly or entirely absent.

(Figures [a] and [b] from Bock K, Ramaswamy A, Köhler H. Fortbildungskurs zur Aufrechterhaltung und Weiterentwicklung der fachlichen Befähigung für Pathologen [6.10.2012]—Referenzzentrum Mammographie Südwest am Universitätsklinikum Gießen-Marburg am Standort Marburg [Course text].)

Columnar Cell Lesions and Flat Epithelial Atypia

With the introduction of systematic radiographic screening for breast cancer, findings referred to as columnar or cylindrical cell lesions have gained in significance. The following forms are histopathologically distinguished:

Columnar cell metaplasia: The normally double-layered epithelium of the lobules and terminal intra-acinar ducts is replaced by a single layer of cylindrical epithelium with apical apocrine cytoplasmic constrictions (“apical snouts”). The abnormal apocrine secretion causes ectasia of the lobular lumina. Secretory calcifications, which may appear as slightly polymorphic, grouped calcifications on mammography, are not rare. One form of columnar cell metaplasia is the blunt duct adenosis, in which multiple lobules are lined with ductlike columnar cells.

Columnar cell hyperplasia: This form is characterized by focal overlapping of the cylindrical cells (crowding) without signs of cytologic atypia.

FEA: Lobules are lined by a relatively uniform cell population with monotonically enlarged and rounded nuclei, in which the chromatin is usually lighter in the center and one or two prominent nucleoli are seen (▶ Fig. 3.5b). The epithelium is frequently single-layered along the duct contour. If the lobule boundary is overpassed and there is expansion to the interlobular ducts, then it corresponds to the monomorphic-type clinging carcinoma (low-grade DCIS). The breast cancer risk associated with columnar cell lesions is considered to be low, and has been overestimated (in small-scale studies) even when an FEA was verified. An increased cancer risk is only certain once an ADH has been verified.

Atypical Ductal Hyperplasia

The characteristic feature of ADH that distinguishes it from FEA is the verifiable formation of micropapillae and cell bridges (so-called secondary architectures; ▶ Fig. 3.5d). It is distinguished from low grade DCIS by the number and size of ducts affected either a maximum of two affected ducts (as per Page) or one lesion smaller than 2 mm (as per Tavassoli). Strictly speaking, the ADH lesion is limited to one lobule. The transition to a DCIS is indicated when multiple lobules are affected or if the atypia encroaches upon interlobular ducts. ADH increases the risk of developing breast cancer 3-fold to 5-fold. 46

Lobular Neoplasia

Cell proliferations in the terminal lobules (▶ Fig. 3.6 and ▶ Table 3.2) are called lobular neoplasia and include atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH) and lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS). Analogous to intraductal neoplasia, these lesions are also referred to together using the term “lobular intraepithelial neoplasia” (LIN). Together with other histologically benign breast findings, they are usually found incidentally in approximately 0.5 to 5% of cases. The lesions are usually multicentric (85% of cases) and often bilateral (30–67%). With few exceptions, there are no clinical or mammographic findings that can be called typical. 26

Fig. 3.6 Types of lobular neoplasia. (a) Atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH) with uniform, atypical cells filling the lobules that do not cause significant ectasia. Some of the gland lumina are still visible to some extent, and the myoepithelial layer is essentially intact (cytokeratin CK5/6 immunostaining). (b) Classic lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) with ectatic and deformed acini. (c) Pleomorphic lobular carcinoma with pronounced ectatic glands that are filled with atypical pleomorphic tumor cells and central necroses. (d) Extension of LCIS into neighboring ducts (below), partially with so-called pagetoid spread, interfusing the ductal epithelia with single cells or small cell groups (arrows). Immunostaining for the cell adhesion molecule E-cadherin (strong brown staining) is present in ductal epithelia but is absent from the lobular neoplasia (tumor cells shown only blue nuclei using haemalum as counterstain).

(From Bock K, Ramaswamy A, Köhler H. Fortbildungskurs zur Aufrechterhaltung und Weiterentwicklung der fachlichen Befähigung für Pathologen [6.10.2012]—Referenzzentrum Mammographie Südwest am Universitätsklinikum Gießen-Marburg am Standort Marburg [Course text].)

Spectrum of lobular neoplasia (WHO 2012) | LIN classification (WHO 2003) | Definition | Associated DCIS | Associated IDC (NST) | Associated ILC |

ALH | LIN 1 | Less than 50% of TDLU filled, not distended | in 7.7% | in 12.3% | in 1.5% |

LCIS | LIN 2 | More than 50% of TDLU affected, distended | in 14.7% | in 9.4% | in 8.2% |

Pleomorphic LCIS | LIN 3 | Maximum distention of TDLU, pleomorphic with necroses | in 18.5% | in 3.3% | in 19.6% |

Abbreviations: IDC, invasive ductal carcinoma. ILC, invasive lobular carcinoma. NST, no special type. TDLU, terminal duct lobular unit. | |||||

The histological findings include a solid epithelial proliferation originating in the lobules, with relatively small, monomorphic cells and nuclei with no prominent nucleoli. The lobules are ectatic, but the architecture remains intact. If the lobules are not ectatic, or if only few acini (less than 50%) are filled with solid, atypical cell proliferations, then the lesion is an ALH. The characteristic and not uncommon feature of lobular neoplasia is pagetoid growth in the terminal ductules, with growth undermining the still intact luminal ductal cell layer. The classic cell type (A), with only slight cell atypia, must be distinguished from cell type B, which has prominent nucleoli and coarse chromatin. If there is a preponderance of cell type B, the lesion is a pleomorphic lobular neoplasia, which may be accompanied by necrosis and increased mitosis (also called LIN 3). Immunohistochemical methods are used to distinguish lobular neoplasia, particularly the LIN 3 lesion, from lobule cancerization as seen in DCIS. Unlike DCIS, lobular neoplasias are E-cadherin negative in the majority of cases. 26

Note

Although the presence of lobular neoplasia increases the risk of developing cancer by a factor of 7 to 12, it is not invariably a precancerous lesion.

The risk of developing a subsequent invasive carcinoma is approximately 20% in 10 years (20% ipsilateral, 10% contralateral); if more than five lobules are affected, or if there is a family history of cancer, then the risk is even higher. Approximately 35% of women with a lobular neoplasia develop an invasive carcinoma after 35 years. Lifelong aftercare and monitoring, with and without tamoxifen treatment, is recommended. In the case of LIN 3, the risk of cancer is significantly higher (▶ Table 3.2). If this type of lesion is found, the aim of surgery should be complete excision of the lesion with clear lesion borders. 5

Fibroepithelial Tumors

Fibroadenomas and phyllodes tumors are biphasic tumors that consist of an epithelial component and a dominant mesenchymal (or stromal) tissue component. A breast hamartoma is a pseudotumor that also falls into this category.

Fibroadenoma

Fibroadenoma is the third most common form of breast disease (ca. 20% of cases), after mastopathy and carcinoma. Fibroadenomas develop in patients between the ages of 20 and 40 years (peak frequency at ages 20–24 years.). Most fibroadenomas are solitary, and form in the upper outer quadrants; approximately 20% are multiple, and 3 to 5% are bilateral.

The vast majority (ca. 90%) of fibroadenomas are less than 4 cm in diameter, are grayish-white in appearance, and are easily demarcated from the surrounding glandular tissue (▶ Fig. 3.7a). Histological features include a hypocellular myxoid stroma with enclosed, fissurelike lumina lined with flat, double-row epithelia (▶ Fig. 3.7b). The juvenile fibroadenoma that occurs in adolescents (11 to 18 years) must be distinguished from these and is characterized by pseudopapillary epithelial proliferation with dense, hypercellular stroma. The rapid growth of this tumor can lead to what is termed a giant fibroadenoma.

A fibroadenoma can also develop into a phyllodes tumor or a stromal sarcoma. Atypical epithelial proliferations are detected in 1 to 2% of cases, of which approximately 70% are of LCIS type (usually in women over 40 years of age). 40

Fig. 3.7 Fibroadenoma. (a) Sharply defined, ca. 2.2 cm, firm-elastic tumor with grayish-white, whorllike cross section. (b) Histology shows fissurelike ducts, compressed by bulging mantle tissue. The epithelium is flattened (pressure atrophy).

Phyllodes Tumor

The phyllodes tumor (WHO classification 24) or cystosarcoma phylloides (older nomenclature) probably develops from a fibroadenoma, and is characterized by stromal overgrowth with wide fissures and epithelial and mesenchymal metaplasia (▶ Fig. 3.8a). The mean age of patients is some 10 to 20 years older than for fibroadenoma, but it is sometimes seen as early as puberty and as late as postmenopause.

Phyllodes tumors have been described with a diameter of 30 cm and weighing 5,000 g. Histology shows a hypercellular stroma, often made up of spindle cells, with a myxoid matrix. Metaplasias of cartilage, bone, adipose tissue, and squamous epithelia are common. The presence of fewer than 4 mitoses per 10 high-power fields [HPF], a lack of cell atypia, and sharply defined tumor margins indicate benignity. Approximately 65% of phyllodes tumors are benign. Roughly 15% of phyllodes tumors are malignant (stromal sarcoma), which primarily metastasize hematogenously. The verification of increased numbers of mitoses (over 10 per 10 HPF), atypical, hypercellular stroma, and invasive growth at the tumor margin are together considered to be reliable criteria for determining malignancy (▶ Fig. 3.8b). The rate of recurrence is quite high (ca. 30%).

Fig. 3.8 Phyllodes tumor. (a) Phyllodes tumor with clover leaf–like, lobed structure. (b) The phyllodes tumor has a widened epithelial layer with, in this example, pleomorphic nuclei, and a hypercellular stromal base (indicators of malignancy are the verification of increased mitoses, necroses, and invasive growth).

Breast Hamartoma

Hamartomas (also termed fibroadenolipomas) are well-defined pseudotumors of the breast that have a surrounding connective tissue pseudocapsule. These range from 1 to 20 cm in size and are made up histologically of all breast tissue types. The interstitial tissue contains lobules and a large amount of fibrolipomatous tissue. Macroscopically, these easily enucleated lumps appear like normal breast tissue (“breast within a breast” impression) or like a lipoma. This hamartomatous neoplasm arises from a local maldifferentiation and is rare (0.16% of all lumps detected in mammography). It shows no age preference and has no malignant potential.

Mesenchymal (Nonsarcomatous) Tumors

Changes originating in the mesenchyme of the breast essentially correspond to those found in extramammary soft tissue; they are therefore described only briefly here.

Hemangioma

The hemangioma is a circumscribed tumor (0.6–2.5 cm in diameter) with grouped, dilated (cavernous) or narrow-lumened (capillary), blood-filled vessels (▶ Fig. 3.9a). Complete excision is recommended for reliable differentiation from an angiosarcoma. 6 Diffuse angiomatoses are rare.

Fig. 3.9 Benign mesenchymal tumors. (a) Hemangioma with clustered blood-filled capillary sprouts in the mammary stroma (left) located between the normal glands (right). (b) Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH; see text) with fissured, angiomalike connective tissue reaction (but, unlike hemangioma, CD31 negative). (c) Fibromatosis (extra-abdominal desmoid tumor) with spindlelike fibroblasts arranged in alignment, typically indistinctly circumscribed at the margins (high recurrence rate). Unlike scar tissue (insert), fibromatosis displays a positive nuclear β-catenin staining. (d) Granular cell tumor with granular, foam cell–like proliferation of S 100-positive (Schwann) cells (insert).

(Figures [c] and [d] from Bock K, Ramaswamy A, Köhler H. Fortbildungskurs zur Aufrechterhaltung und Weiterentwicklung der fachlichen Befähigung für Pathologen [6.10.2012]—Referenzzentrum Mammographie Südwest am Universitätsklinikum Gießen-Marburg am Standort Marburg [Course text].)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree