3 Pathology of the Temporal Bone

Pathology of the External Auditory Canal

Inclusion Cholesteatoma and Atresia of the External Auditory Canal

Differential Diagnosis

• Any benign mass in the region of the external auditory canal, post-traumatic cholesteatoma of the external auditory canal, or cholesteatoma due to secondary stenosis of the external auditory canal as a result of chronic cicatrizing external otitis or bony stenosis due to fibrous dysplasia or exostosis in the lateral part of the external auditory canal.

• Aural atresia is often related to syndromes such as Treacher Collins, Crouzon, Nager, Goldenhar, Klippel—Feil, and Pierre Robin.

Points of Evaluation

• Expansion toward and/or destruction of the temporomandibular joint and toward the middle ear structures, abscess formation, and osteomyelitis and (intracranial) spread of infection.

• In case of aural atresia (first branchial groove anomaly), other dysmorphic features may be present too, especially in case of syndromal comorbidity.

• Particular attention needs to be paid to:

– the appearance of the middle ear cavity and mastoid pneumatization

– signs of ankylosis or malformation of the ossicular chain

– presence of inner ear deformities, the round and oval windows and the vestibular aqueduct

– aberrations in the anterior and/or lateral course of the facial nerve, which may complicate surgery.

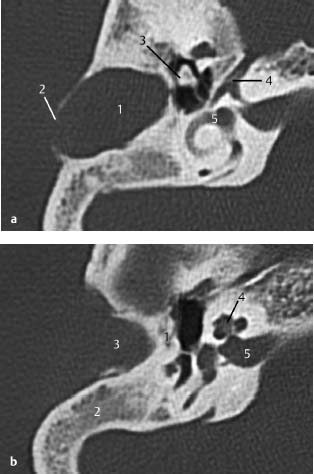

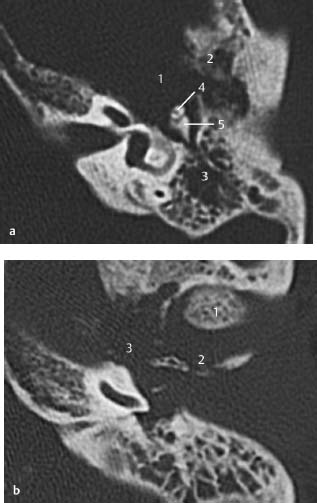

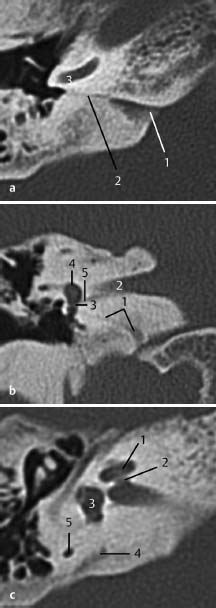

Fig.3.1 a–c Patient with Treacher Collins syndrome and purulent discharge from a pinpoint external auditory canal.

a CT, axial. Expanding, round, smooth-bordered lesion (1) in the cranial part of the mastoid with partial destruction of the cortex (2). The head of the malleus is possibly dysmorphic and ankylotic (3). Note the geniculate ganglion (4) with a clearly visible greater petrosal nerve canal anteriorly. The vestibule and horizontal semicircular canal (5) are normal.

b CT, axial. More caudally, osseous atresia of the external auditory canal is observed with osseous occlusion (1). The mastoid is not pneumatized (2). Lateral to the atresia is an expanding mass (3), suggestive of inclusion cholesteatoma, filling the meatus. The cochlea (4) and internal auditory canal (5) show normal features.

c CT, axial. On a lower slice, a narrowed and endingobstructed meatus is observed (1), as well as an expansile mass (2) near the temporomandibular joint (3) without signs of destruction. The slice is taken at the level of the basal cochlear turn (4) and of the roof a high jugular bulb (5).

Exostoses of the External Auditory Canal

Differential Diagnosis

• Exostoses are frequently multiple and bilateral.

• An osteoma of the external auditory canal is most often unilateral, isolated, and round in shape.

• Fibrous dysplasia has a specific appearance on computed tomography (CT) and typically is not limited to the external auditory canal (see also “Fibrous Dysplasia” [1] and [2]).

• Clinically, exostoses can be easily differentiated from soft-tissue tumors by palpation.

Points of Evaluation

• In patients with aural discharge, chronic otitis may be the result of infected epithelial stasis.

• In cases with a narrowed orifice and meatus, a meatoplasty might be considered for better aeration and cleaning options. Furthermore, CT might be reassuring, showing a normal aerated middle ear.

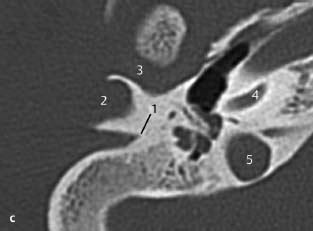

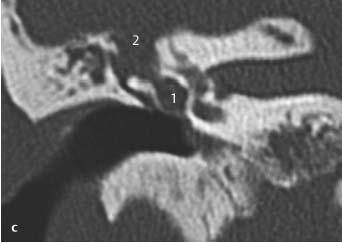

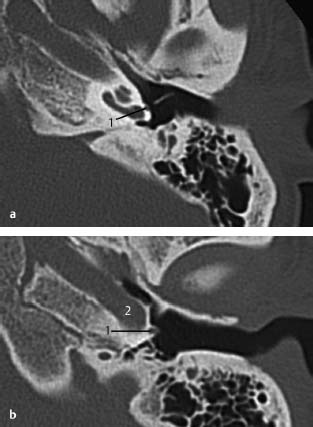

Fig. 3.2 a Patient referred by his general practitioner because of abnormalities in the outer ear canal.

a CT, axial. Small exostoses are visualized in the roof of the external auditory canal near the annulus (1), and a larger one laterally on the floor of the meatus (2). Although some accumulation of cerumen (3) is present, hearing did not seem to be compromised, and there was no discharge. Also clearly seen are the basal cochlear turn (4), vestibule (5), and horizontal (6) and anterior (7) semicircular canals.

Fig. 3.2b Another patient with more extensive exostoses.

b CT, axial. Only a small lumen remains (1), with accumulation of cerumen or epithelium more medially (2) with a high risk of impaction and development of an inclusion cholesteatoma. Note the internal carotid artery (3), indicating the caudal orientation of this slice.

Stenosis of the External Auditory Canal

Differential Diagnosis

• Clinically, the fibrous wall has a classic appearance with a smooth and dry cicatrized skin surface. In patients with active mucosal proliferation, malignant external otitis must be considered.

• Secondary stenosis might be due to trauma (see “Skull Base Fractures”) or previous canal surgery with cicatrization of the external auditory canal.

• Expanding lesions might indicate soft-tissue tumors such as (secondary) cholesteatoma, ceruminous gland tumors, and squamous cell carcinomas.

Points of Evaluation

• Beware of accumulation of cerumen or epithelium behind the fibrous wall, and exclude deeper pathology in the middle ear. In most cases, the fibrous wall can be surgically separated from the inner layers of the eardrum without opening the middle ear.

• In cases of malignant external otitis or secondary cholesteatoma, deeper pathologies (e.g., to the facial nerve) are of special interest.

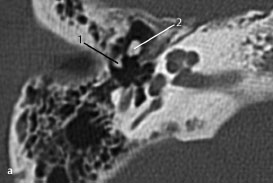

Fig.3.3 a, b Patient with a history of chronic otitis externa.

a CT, axial. Chronic external otitis may lead to cicatrizing fibrous changes in the wall (1) of the external auditory canal. In this patient, the fibrous wall is located on the external side of the eardrum, resulting in conductive hearing loss. The middle ear is normal (2), excluding additional pathology.

b CT, coronal. The fibrous wall (1) seen in Fig.3.3 a is also seen on this anteriorly located coronal slice. The pathology on this view is limited laterally by the malleus and the eardrum.

Malignant External Otitis or Necrotizing External Otitis

Differential Diagnosis

Malignant masses such as ceruminous gland tumors, basal cell tumors, and squamous cell tumors with destructive characteristics, and growth of tumors from regional areas.

Points of Evaluation

• Risk of facial nerve damage, which may lead to paresis or paralysis, as a result of extensive destruction of the area of the facial nerve, although bacterial spread may precede the signs of bony destruction.

• Beware of deeper pathologies, such as middle ear infection or intracranial complications, and risk factors such as diabetes. A swab may reveal Pseudomonas aeruginosa in most patients, or Aspergillus species in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive patients.

• Malignant masses can present with the same destructive growth pattern as malignant external otitis.

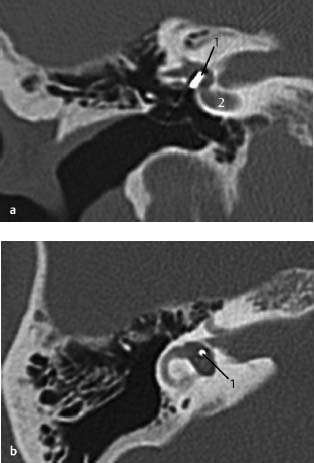

Fig.3.4 a Patient with severe auricular pain and some discharge.

a CT, coronal. Necrotizing lesion in the floor of the external auditory canal (1). Clinically, erosive bone lesions (2) with purulent debris and denuded bone were evident. Spread of infection to the facial nerve at the point where it exits the stylomastoid foramen (3), or in its vertical portion (4), is a serious risk and complication.

Fig.3.4b Patient presenting with facial paresis.

b CT, axial. An axial slice through the debris (1) in the floor of the external auditory canal. Erosive destruction of the anterior wall (2) of the temporomandibular joint is also seen, as well as posterior bony erosion (3) extending to the facial nerve canal (4), which was involved as demonstrated clinically.

Malignancy of the External Auditory Canal—Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Differential Diagnosis

• Any regional structure that might show malignant changes, such as tumors of the external auditory canal and external ear (i.e., ceruminous gland tumors or squamous cell tumors, middle ear tumors, extended parotid gland tumors).

• Intracranial tumors rarely invade bone and frequently give rise to raised intracranial pressure with resulting symptoms.

Points of Evaluation

• Extension of bony destruction and features suggestive of infiltrative growth are associated with high morbidity, such as dysfunction of the facial nerve and inner ear.

• Adherence to vital structures, such as the internal carotid artery, may preclude surgery.

• Secondary complications, i.e., mastoiditis or otitis media, as a result of stasis of secretions due to obstruction of the eustachian tube. After radiotherapy, necrotizing osteomyelitis and mastoiditis may occur.

Fig.3.5 a, b Patient with granular proliferations in the outer ear canal.

a CT, axial. Cranial slice at the level of the horizontal canal, showing destruction of the wall of anterior epitympanum (1), irregular invasion of bone, and infiltration toward the zygomatic arch and lateral skull (2). The opacification of the mastoid (3) is probably due to secondary stasis of mucus, which in turn is caused by obstruction of the eustachian tube by the lesion. The head of malleus (4) and incus (5) are intact.

b CT, axial. Another slice at a lower level through the basal turn of the cochlea, showing anterior displacement of the mandibular condyle (1), probably due to mass effects of the tumor and extensive, irregular bony destruction in the region of the anterior external auditory canal (2), all suggestive of malignancy. In this slice, the opening of the eustachian tube (3) is obstructed by the tumor.

Fixation of the Ossicular Chain

Differential Diagnosis

• Congenital deformities, often in relation to aural atresia (see also p.23) and its related syndromes, such as Treacher Collins, Crouzon, Nager, Goldenhar, Klippel–Feil, and Pierre Robin.

• Fixation may also be due to otosclerosis (demineralization of the otic capsule), osteogenesis imperfecta (demineralization of otic capsule and history of multiple fractures), tympanosclerosis (myringosclerosis of the eardrum),or mass effects on the ossicular chain (congenital cholesteatoma, facial nerve schwannoma, dural prolapse, or any other middle ear tumor).

• A history of recurrent infections or trauma might be relevant.

Points of Evaluation

• As mentioned above in differential diagnosis, particular attention must be paid to patients with conductive hearing loss in combination with a normal appearing eardrum and aerated middle ear.

• In case of ankylosis of the ossicular chain, accurate evaluation of thin axial and coronal slices may reveal deformities and/or fixation.

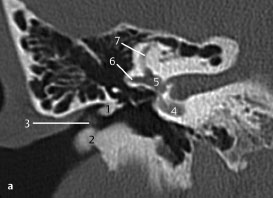

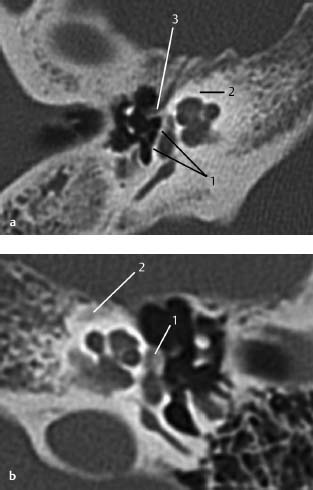

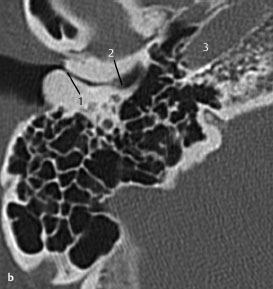

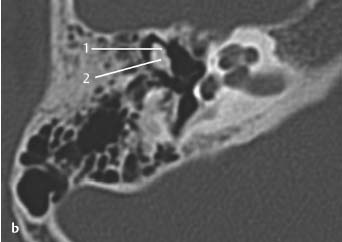

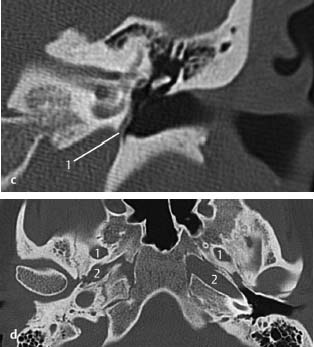

Fig.3.6 a, b Child with congenital microtia, bony atresia of the external auditory canal, and complete conductive hearing loss.

a CT, axial. Although the conductive hearing loss might be ascribed to the atresia, the handle of the malleus (1) is fixed to the lateral bony wall of the middle ear (2), at the expected location of the atretic external auditory canal.

b CT, axial. On a more superior slice through the epitympanum, the incudomalleal joint between the head of malleus (1) and the body of incus (2) is not clearly visible. These ossicles are deformed and appear as one bony mass due to fixation. No inner ear deformities are seen.

Fig.3.6 c In another patient with conductive hearing loss and signs of otitis media with effusion, a completely different pathology resulted in ossicular chain fixation.

c CT, coronal. Paracentesis revealed a constant loss of watery fluid, which proved to be cerebrospinal fluid. The conductive hearing loss persisted. On CT, the middle ear is fully opacified (1). The bony outline to the fossa media (tegmen tympani) was destroyed (2). At surgery, this situation was revealed to be dural prolapse with compression of the ossicular chain.

Luxation of the Ossicular Chain

Differential Diagnosis

• Congenital anomaly of the ossicular chain with a fibrous connection between the incus and stapes.

• Skull base fracture lines through the petrosal bone and opacification of the middle ear and mastoid cells due to hematoma.

• Middle ear masses with destruction of the ossicular chain, most frequently cholesteatoma (see also “Fixation of the Ossicular Chain” above). Luxation of previously placed ossicular interposition.

Points of Evaluation

• Consider the differential diagnosis, pay attention to opacifications as well as the presence and pattern of fracture lines. Always study both axial and coronal planes for accurate evaluation.

• Slowly progressive conductive hearing loss and localized opacifications in the middle ear are indicative of erosive middle ear masses.

• In all cases of trauma, clinically attention must be paid to inner ear damage and (delayed) facial nerve dysfunction.

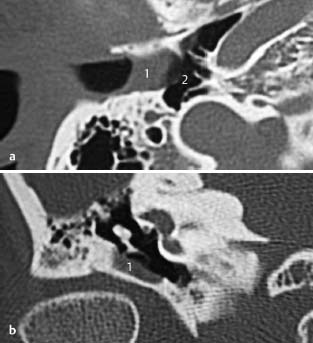

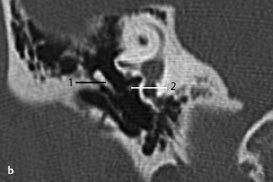

Fig.3.7 a Patient with aural pain and conductive hearing loss following deep cleaning of the external auditory canal with a Q-tip.

a CT, axial. Traumatic luxation with dislocation of the connection between incus (1) and malleus (2) is seen. The typical icecone configuration of the malleus head and incus body is lost.

Fig.3.7b This patient received a blow on the outer ear.

b CT, coronal. There was traumatic dislocation of the connection between incus (1) and stapes (2) due to barotrauma caused by sudden displacement of the eardrum. No perforation occurred, although this outcome is often seen in such patients.

Stapedectomy, Control of Piston Position

Differential Diagnosis

• Luxation of the piston due to displacement from the footplate or erosion of the incus typically presents as sudden recurrent conductive hearing loss.

• Fibrous adhesions may be found but their contribution to a renewed conductive hearing loss is doubtful.

Points of Evaluation

• Ossicular prostheses may differ as regards their degree of radiopacity and visibility on CT. For this reason fine slices are required.

• Malpositioning of the piston around the incus and possible erosions or resorbtion of the long process and lenticular process due to compression of the piston are difficult to evaluate on CT.

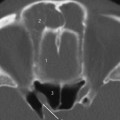

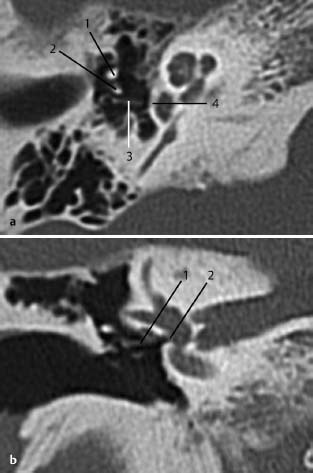

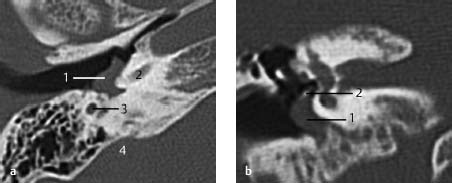

Fig.3.8 a, b Patient with recurrent conductive hearing loss after stapedectomy and history of reconstruction a few years earlier.

a CT, axial. This view shows the handle of malleus (1) and posterior to it the long process of the incus (2), and a completely luxated piston (3)—from both its position in the footplate (4) and its connection to the incus.

b CT, coronal. The dislocated prosthesis (1) outside the hole in the footplate (2). Luxation is sometimes difficult to diagnose on this view. These images emphasize the importance of combining views from different planes.

Fig.3.9 a,b Patient with a history of bilateral stapedotomy.

a CT, coronal. The piston is positioned (1, coronal and axial) deep in the vestibule through the footplate. Note also the basal cochlear turn (2).

b CT, axial. Theoretically, the piston seemed to be inserted too deep into the vestibule and vestibular disorders were expected. However, this patient was operated on 30 years previously on both sides and had had no vestibular problems since.

Otosclerosis, Radiologic Signs around the Oval Niche

Differential Diagnosis

• Osteogenesis imperfecta (mostly fracture of the stapedial crus in combination with fixation of the footplate, blue sclerae depending on the genetic subtype).

• Other causes of conductive hearing loss without signs of masses in the middle ear or retraction pockets of the eardrum. See also “Fixation of the Ossicular Chain” and “Luxation of the Ossicular Chain,” pages 32 and 34.

Points of Evaluation

• Absence of radiologic signs does not exclude otosclerosis.

• Early signs of otosclerotic foci on the medial wall of the cochlea are difficult to recognize, and particular attention must be paid to this situation in the evaluation of patients with conductive hearing loss of unknown cause.

• Lesions might be unilateral or bilateral.

• Family history might be positive.

• Progression of the hearing loss may occur during pregnancy.

Other radiologic signs of otosclerosis of the otic capsule are described in the inner ear section.

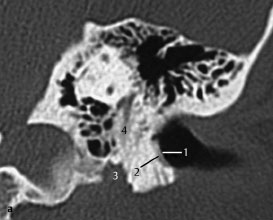

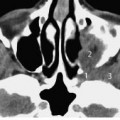

Fig.3.10 a, b Patient with conductive hearing loss of unknown etiology, without abnormalities of otoscopy.

a CT, axial. At the edges of the footplate, two densities are visible (1), indicating osseous thickening, which may be considered as otosclerotic foci, especially in combination with the lucent area anterior to the footplate (more clearly demonstrated in Fig.3.10b). Slight demineralization seems to be present in the otic capsule (2). There is a good view of the cochleariform process and tensor tympani (3).

b CT, axial. Fenestral otosclerosis as illustrated by a hypodense lesion in the region of the fissula ante fenestram (1), which is frequently an early sign of otosclerosis. In most cases, the lucencies due to demineralization of the otic capsule (retrofenestral otosclerosis) are somewhat more pronounced (2); in this case this sign is very subtle or not seen.

Without any pathology, the stapedial crura are difficult to visualize on CT, not only due to their fine structure, but also due to the partial volume effect. This effect appears as “blurring” over sharp edges. It is due to the scanner being unable to differentiate between a small amount of high-density (e.g. crural bone) and a larger amount of lower-density (e.g. air or soft tissues) material. The processor tries to average out the two densities or structures and information is lost.

In osteogenesis imperfecta, the crura may even be thinner and more difficult to visualize, and may be more prone to fractures. Furthermore, the findings in osteogenesis imperfecta may be similar to those in otosclerosis. A more extensive case is illustrated in the section on the inner ear.

Differential Diagnosis

Otosclerosis. Other causes of conductive hearing loss without signs of masses in the middle ear or retraction pockets of the eardrum. See also “Fixation of the Ossicular Chain” and “Luxation of the Ossicular Chain,” pages 32 and 34.

Points of Evaluation

In osteogenesis imperfecta affecting the middle ear, fractures of the stapedial crus are often found on middle ear inspection and/or fixation of the footplate in combination with a known (family) history of osteogenesis imperfecta. Note the typical blue sclerae of the eyes in osteogenesis imperfecta type I.

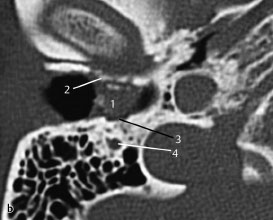

Fig.3.11 Patient with osteogenesis imperfecta and conductive hearing loss evaluated with CT, coronal.

The radiologist explicitly described an enlarged stapedial head (1). In this case, no thickening of the footplate (2) is noted. In the region of the fissula ante fenestram, a lucency as suggested on this view (3) was excluded on evaluation of sequential slices.

Fig.3.12 a–c Patient with conductive hearing loss and fixation of the footplate noted on middle ear exploration.

a CT, axial. At stapedotomy, abundant flow of inner ear fluid, the gusher phenomenon, made further surgical exploration impossible and the hole in the footplate was closed with fat and fascia of the temporal muscle. Attention must be paid to an abnormal widened cochlear aqueduct. In this case, the aperture of the cochlear aqueduct is not pathologically widened (1), although there are no agreed criteria about size in the literature. The cochlear aqueduct (2), originating from the basal cochlear turn (3), is visible on three successive 1-mm slices, suggestive of a larger size compared with nongushers.

b CT, coronal. In the coronal slice, the cochlear aqueduct (1) is seen to run below the internal auditory canal (2) to the round window (3), and the region of the basal cochlear turn and vestibule (4). Note the inferior vestibular nerve (5). In this patient, no abnormalities were observed.

c CT, axial. Gusher is associated with other abnormal communications between the subarachnoid spaces and the perilymphatic space. Although none of these seem to be present in this patient, attention must also be paid to internal auditory canal abnormalities such as lack of a bony partition between the meatus and cochlear fundus, widened cochlear aqueduct, or cochlear anomalies (e.g., Mondini). The cochlea (1), fundus (2), vestibule (3) are normal. Also, the vestibular aqueduct (4), which according to some publications, may have a maximal diameter similar to the diameter of the posterior semicircular canal (5).

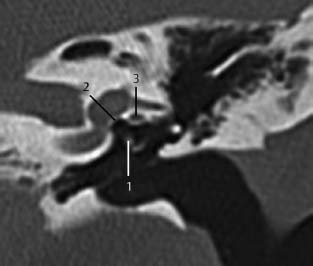

Fig.3.13 a–d A patient operated on for suspected otosclerosis. The surgeon encountered a surprise at the time of middle ear exploration. A pulsatile vessel was seen on the promontory, partially covered by bone, which can be suggestive of an atypical glomus tympanicum.

a CT, axial. A retrospective close examination of the CT scan revealed the stapedial artery passing along the wall of the promontory (1), between the crura of the stapes, and entering the tympanic segment of the facial canal, resulting in a broadened facial canal on CT (not shown on this slice).

b CT, axial. The artery (1) represents the intratympanic origin of the middle meningeal artery from the internal carotid artery (2), and leaves the facial canal at the geniculate ganglion to exit the middle cranial fossa.

c CT, coronal. On the coronal view, its origin from the internal carotid artery and passage to the promontory is shown.

d CT, axial. On this axial skull base view, the typical absence of the foramen spinosum through which the artery usually runs, is indicative of this finding. Posteriorly, from the foramen ovale (1) and, anteriorly, from the internal carotid artery (2), the foramen spinosum should be present in normal cases (see also Chapter 4). In this case, the foramen spinosum was absent on both sides with a bilateral persistent stapedial artery. It is also known to be associated with an aberrant or aneurysmal internal carotid artery.

Glomus Tympanicum (Paraganglioma)

Differential Diagnosis

• Glomus jugulotympanicum. Endolymphatic sac tumor with destructive growth toward the middle ear (strongly associated with Von Hippel–Lindau disease; see also “Pathology of the Facial Nerve,” p.66, and Chapter 5).

• Less likely in this patient, due to the lack of evident pulsating red masses, the following must also be considered: adenoma of the middle ear and congenital cholesteatoma with a red appearance due to granulation mucositis posterior to the eardrum.

Points of Evaluation

• Glomus tympanicum is limited to the middle ear, whereas in glomus jugulotympanicum there are signs of bony destruction in the region of the jugular bulb and jugular foramen, and a salt and pepper configuration on MRI.

• Glomus jugulotympanicum is associated with higher morbidity and a less favorable outcome due to palsies of cranial nerves IX, X, and XI, and extension into structures of the neck and skull base (see also Chapter 5).

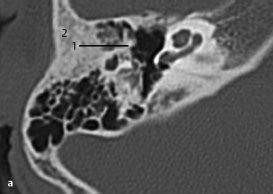

Fig.3.14 a, b Patient with a pulsating red-blue mass posterior and caudal to the eardrum.

a CT, axial. On this axial slice at the level of the hypotympanum, a smooth-bordered lesion (1) is seen, without any destruction of the cochlea (2) or vertical part of the facial nerve canal (3). Since there seems to be no connection to the jugular bulb or jugular vein (4), this lesion may be considered to be a glomus temporale type A.

b CT, coronal.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree