Hashimoto’s thyroiditis

Graves’ disease

Silent thyroiditis

Postpartum thyroiditis

Subacute thyroiditis

Suppurative thyroiditis

Drug-induced thyroiditis

Iodine deficiency

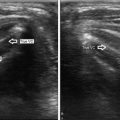

Fig. 16.1

Diffuse thyroid enlargement . Thickened AP dimension of the isthmus (1.1 cm) in this patient with Hashimoto’s. Normal AP dimension of the isthmus is typically less than 0.5 cm

Fig. 16.2

Enlarged isthmus . The isthmus is enlarged on this sagittal view. Note the heterogeneous and hypoechoic echotexture

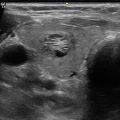

Fig. 16.3

Early changes of chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis . Left lobe sagittal image showing mild heterogeneity and a pseudomicronodular pattern. The pattern is often more easily recognized on real-time imaging

16.2 Chronic Lymphocytic (Hashimoto’s) Thyroiditis (CLT)

Chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis is the most common form of thyroiditis. Approximately 10 % of the US population overall and an estimated 25 % of women over the age of 65 years exhibit antibodies to thyroperoxidase [2]. The presence of thyroid autoantibodies predicts future thyroid dysfunction in patients who are currently euthyroid. The pathologic hallmark of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is lymphocytic infiltration of the gland by B cells and cytotoxic T cells. This results in an overall decrease in parenchymal echogenicity on ultrasound, as the lymphocytic infiltrate allows greater through transmission of sound than the intact thyroid follicles that reflect sound. This hypoechogenicity has been used to predict the presence of autoimmune thyroid disease and the risk of subsequent hypothyroidism. Pederson studied 485 patients with diffuse thyroid hypoechogenicity and 100 normal patients and found that hypoechogenicity had a positive predictive value of autoimmune thyroid disease of 88 % and a negative predictive value of 95 % [3]. Hypoechogenicity of the parenchyma on ultrasound has been shown to have a greater predictive value for development of hypothyroidism than the presence of thyroid autoantibodies [4, 5]. However, in morbidly obese patients, the thyroid may appear more hypoechoic, and this finding is less predictive of autoimmune thyroid disease [6].

Similar to the clinical presentation and the histopathologic findings, the degree of change in echogenicity seen in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is quite variable. Normal thyroid parenchyma has a relatively homogeneous appearance that is significantly brighter (more hyperechoic) than the surrounding strap muscles which are typically markedly hypoechoic. As the lymphocytic infiltration progresses, the echogenicity decreases, approaching that of the surrounding strap muscles and in some cases becoming even more hypoechoic than the strap muscles as shown in Fig. 16.5. In general, the progression and degree of hypoechogenicity are predictive of the severity of hypothyroidism [7].

Heterogeneity is another common ultrasonographic feature of autoimmune thyroid disease. A variety of patterns are seen in CLT, reflecting the histopathologic features and the dynamic nature of chronic inflammatory disease (Figs. 16.6 and 16.7). Hallmark pathologic findings include lymphoplasmacytic aggregates with germinal centers, atrophic thyroid follicles, oxyphilic change of the epithelial cells (Hürthle cells), and fibrosis [8]. The patchy nature of these changes produces regional parenchymal distortion that has been described as a pseudonodular appearance. The degree of hypoechogenicity as well as pseudonodular changes in the gland correlates with the titer of thyroperoxidase antibody, but not thyroglobulin antibody [9].

The changes of CLT can be described by seven different patterns or types of appearances [10] and are listed in Table 16.2. These patterns do not necessarily represent a sequential progression. While fibrosis and atrophy are typically later events, any of the other patterns can be seen early in the disorder. The inflammation may diffusely involve the thyroid or be geographic in nature .

Table 16.2

Sonographic patterns of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis

Hypoechoic and heterogeneous |

Pseudomicronodular |

Pseudomacronodular |

Profoundly hypoechoic |

Developing fibrosis |

Hyperechoic |

Speckled |

16.3 Patterns of Heterogeneity Seen in Chronic Lymphocytic Thyroiditis

16.3.1 Pattern 1: Hypoechoic and Heterogeneous

Normal thyroid tissue has an echogenicity that is hyperechoic compared to muscle tissue and is relatively homogeneous (Fig. 16.4). Areas of lymphocytic infiltration of the thyroid are less echogenic than normal thyroid parenchyma. As a result, areas of lymphocytic infiltration appear hypoechoic compared to normal thyroid. The degree of both hypoechogenicity and heterogeneity varies with the distribution and severity of the lymphocytic infiltration creating a spectrum of patterns within this category (Figs. 16.4, 16.5, 16.6, 16.7, and 16.8).

Fig. 16.4

Normal thyroid compared with chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis . Side-by-side panoramic transverse views. Left panel demonstrates homogeneous echotexture of a normal thyroid. Right panel shows overall hypoechogenicity of the parenchyma, with scatter hypoechoic patchy regions and linear echogenic regions of fibrosis typical of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis

Fig. 16.5

Chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis. Hypoechoic appearance. Transverse image of the left lobe shows decreased parenchyma; echogenicity similar to the surrounding strap muscles (large arrow). Early fibrosis appearing as linear echogenic bands (thin arrow) is also seen

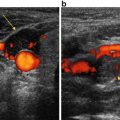

Fig. 16.6

Histologic and sonographic changes of chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis. The histologic appearance (left panel) of Hashimoto’s is varied with geographic areas of lymphocytic infiltration (large arrow) amid preserved groups of follicles (thin arrow), similar to the heterogeneity seen on ultrasound (right panel). On sonography, the hypoechoic areas (large arrows) are regions of lymphocytic infiltration, and the echogenic areas (small arrows) are less affected regions and appear as normal echogenic thyroid parenchyma

Fig. 16.7

Chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis : mild hypoechogenicity . A transverse image of the thyroid obtained in a patient with early chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis shows mild heterogeneity and hypoechogenicity. Note that strap muscles (arrows) are still more hypoechoic than thyroid parenchyma

Fig. 16.8

Chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis : moderate hypoechogenicity . Transverse image of the right lobe shows more marked hypoechogenicity and heterogeneity of the parenchyma. The echogenicity of the thyroid is similar to the surrounding muscles

16.3.2 Pattern 2: Pseudomicronodular

When the areas of inflammation are more discrete, the hypoechoic pattern appears more focal, forming localized hypoechoic regions (pseudonodules ) that represent aggregates of lymphocytes (Figs. 16.3, 16.9, and 16.10). The corresponding histopathology includes numerous germinal centers scattered throughout the gland. The hypoechoic pseudomicronodules are subcentimeter in size and often flame shaped and may have a thin hyperechoic rim, representing surrounding fibrosis or an ill-defined margin. This pattern was first described by Yeh in 1996 [36] as characteristic of CLT and should suggest Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, rather than a multinodular gland. Pseudonodules are occasionally difficult to differentiate from small, multiple true nodules, especially when few in number and they do not involve the entire gland (Fig. 16.9). If an individual pseudonodule appears different, especially with calcifications or infiltrative margins, the possibility of a coexisting malignancy should be entertained. As the inflammatory process is dynamic, the appearance may vary from study to study, with a change in the number, size, or location of the pseudonodules (Video 16.2).

Fig. 16.9

Chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis : pseudomicronodules. Transverse and sagittal views demonstrate multiple subcentimeter hypoechoic areas that represent localized areas of lymphocytic infiltration. The remaining thyroid parenchyma has an isoechoic echotexture

Fig. 16.10

Pseudomicronodules : Swiss cheese pattern. In this pattern the pseudonodules vary in size, have a well-defined border, and replace the much of the normal parenchyma. Reproduced with permission from Springer, Thyroid Ultrasound and Ultrasound-Guided FNA, Editors, Baskin, Duick, and Levine, Chapter 6 pp 99–126

There are two common subpatterns of pseudomicronodules, which I describe as “Swiss cheese” and “honeycomb.” In the former, the areas of inflammation are more discrete and well defined, giving an appearance of numerous well-defined hypoechoic areas (pseudonodules ) similar to the holes in Swiss cheese (Fig. 16.10). In contrast to the Swiss cheese pattern in which multiple discrete pseudonodules are seen within the thyroid parenchyma, the “honeycomb” variant is composed of almost confluent small pseudonodules and marked fibrosis with very little parenchyma separating the hypoechoic tissue (Fig. 16.11).

Fig. 16.11

Pseudomicronodules : honeycomb pattern. Left panel shows transverse view of the left lobe with overlapping bands of fibrosis outlining hypoechoic regions which could be mistaken for multiple hypoechoic nodules. Right panel is the sagittal view which demonstrates the fibrosis and confirms the abnormality as a diffuse process

16.3.3 Pattern 3: Pseudomacronodular Pattern

When the areas of inflammation are larger, pseudonodules also appear larger and again are often mistaken for true large nodules (Fig. 16.12). The pseudonodules may appear confluent, with little or no normal intervening thyroid parenchyma. As always, the possibility of coexisting malignancy should be considered if an individual region has suspicious features .

Fig. 16.12

Pseudomacronodules : hyperechoic banding reflecting marked fibrosis (arrow). In sagittal view, hypoechoic pseudonodules (marked by calipers)

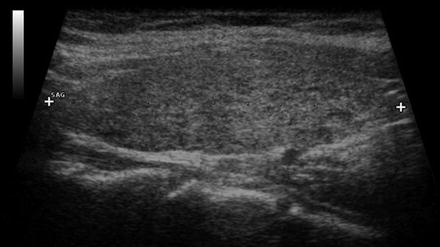

16.3.4 Pattern 4: Profoundly Hypoechoic

This pattern is typically seen with a large, inflamed goiter. The thyroid parenchyma is essentially replaced entirely by lymphocytes, as opposed to discrete germinal centers. The ultrasonographic appearance is relatively homogeneous but profoundly hypoechoic, equal to or darker than adjacent muscle tissue (Fig. 16.13). Importantly, thyroid lymphoma may have a very similar appearance and should be considered in the differential diagnosis, especially if there has been a rapid growth (Video 16.3).

Fig. 16.13

Chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis : profoundly hypoechoic. Transverse image of the left lobe shows marked hypoechogenicity very similar to the strap muscles (arrow). This pattern often seen in clinically swollen thyroid glands. A history of rapid growth should prompt consideration of lymphoma. Reproduced with permission from Springer, Thyroid Ultrasound and Ultrasound-Guided FNA, Editors, Baskin, Duick, and Levine, Chapter 6 pp 99–126

16.3.5 Pattern 5: Developing Fibrosis

Later in the progression of thyroid inflammation, fibrosis develops and appears as hyperechoic linear and curvilinear bands (Figs. 16.14, 16.15, and 16.16). The bands create a pseudonodular appearance by outlining islands of hypoechoic parenchyma with white lines of varying thickness. This appearance of CLT should not be confused with a peri-nodular halo, since a halo surrounding a true nodule is hypoechoic (Fig. 16.12). During real-time imaging in both transverse and longitudinal planes, the band-like nature of the fibrosis can readily be distinguished from underlying nodules. Often these changes are more pronounced in the inferior-posterior aspect of the involved lobe, and a thick band of fibrosis has the appearance of a cleft (Fig. 16.15; Videos 16.4 and 16.5). Often the tubercle of Zuckerkandl becomes prominent in the setting of diffuse thyroid disease and projects from the undersurface of the gland. When the fibrotic bands occur in this portion of the gland, the tubercle can be mistaken for an exophytic nodule (Figs. 16.16 and 16.17 and Video 16.6).

Fig. 16.14

Chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis : developing fibrosis . Developing fibrosis results in hyperechoic bands and echogenic foci without posterior acoustic shadowing. The gland is hypoechoic and the fibrosis appears as subtle white linear echoes of varying lengths (arrow)

Fig. 16.15

Cleft sign. Thick hyperechoic fibrotic band separates the posterior and anterior components of the lobe in transverse view creating the appearance of a hypoechoic nodule (arrow) outlined by an echogenic circle. The appearance should not be misinterpreted as a nodule with a halo, since halos are hypoechoic . On sagittal view, it is evident that there is no discrete nodule. Reproduced with permission from Springer, Thyroid Ultrasound and Ultrasound-Guided FNA, Editors, Baskin, Duick, and Levine, Chapter 6 pp 99–126

Fig. 16.16

Cleft sign. In transverse view, there appears to be a hypoechoic nodule in the posterior aspect of the right lobe (arrow). In sagittal view, it becomes clear that a band of fibrosis created the appearance of a nodule (thin arrow)

Fig. 16.17

Tubercle of Zuckerkandl . This patient was referred after this “nodule” was incidentally discovered on a chest CT done for cough. Previous core biopsy was interpreted as atypical. Real-time imaging was most consistent with a pseudomacronodule due to a prominent tubercle of Zuckerkandl. TPO antibodies were elevated, and second opinion of the outside biopsy was consistent with Hashimoto’s (see also Video 16.6)

16.3.6 Pattern 6: Hyperechoic and Heterogeneous

When fibrosis is more diffuse, the gland may take on a hyperechoic appearance (Fig. 16.18). This pattern has been observed less frequently, but may be more common later in the course of autoimmune hypothyroidism, associated with the start of goiter regression (Video 16.7).

Fig. 16.18

Chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis: hyperechoic and heterogeneous . While the typical pattern in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is hypoechoic, later in the course of the disease, diffuse scarring may predominate over follicles and inflammation resulting in hyperechogenicity. Note the small pretracheal, reactive lymph node (arrow), a frequent finding in autoimmune thyroiditis. Reproduced with permission from Springer, Thyroid Ultrasound and Ultrasound-Guided FNA, Editors, Baskin, Duick, and Levine, Chapter 6 pp 99–126

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree