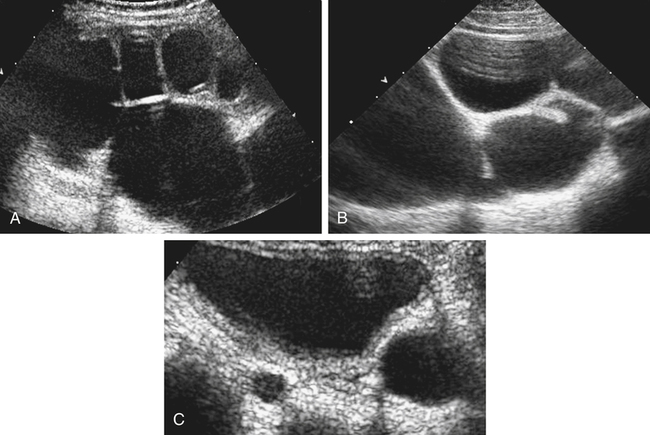

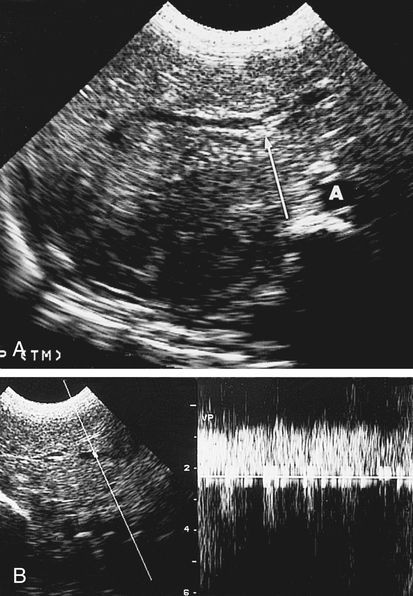

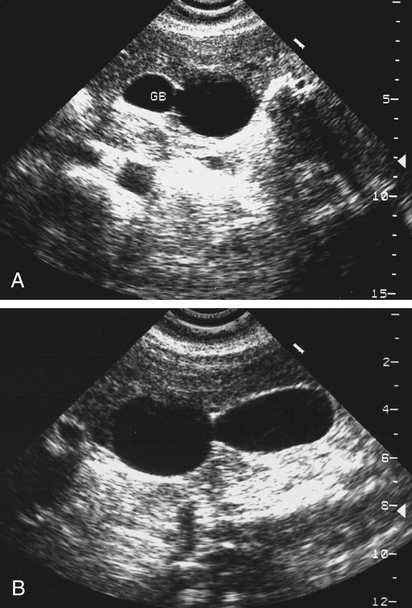

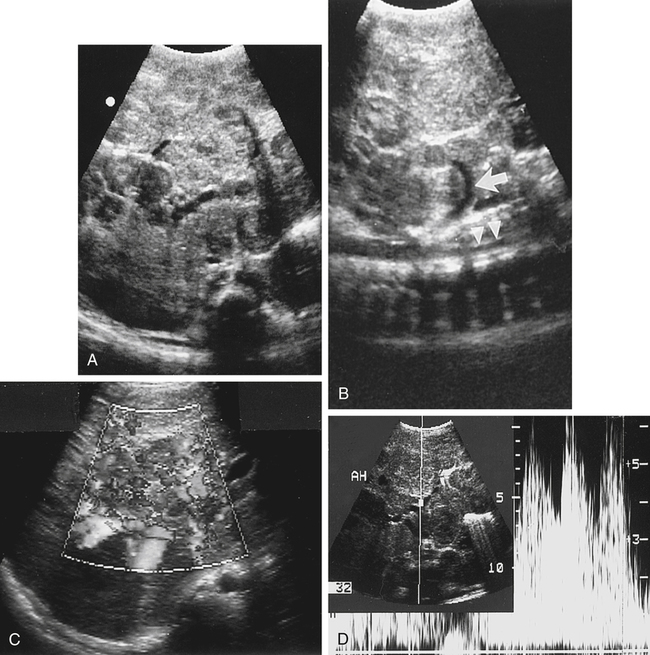

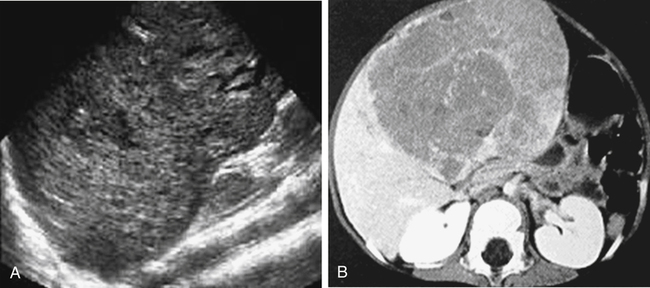

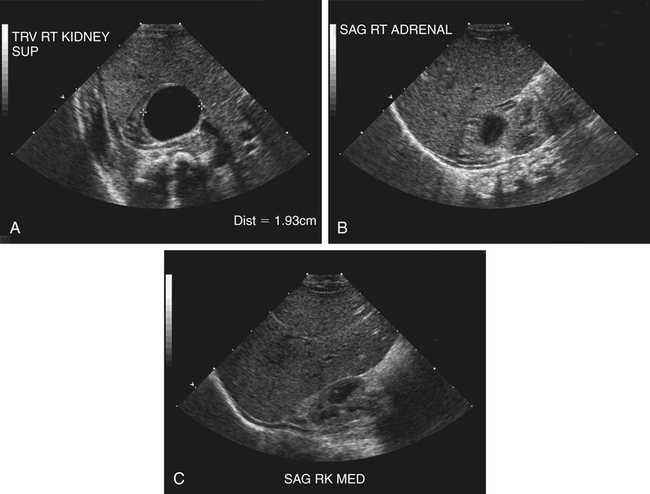

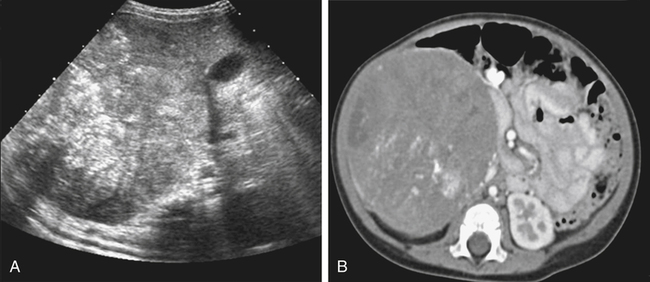

• Describe the sonographic appearance of biliary tract anomalies that are common in the pediatric abdomen. • Differentiate abdominal neoplasms that occur in pediatric patients. • Identify pertinent laboratory values associated with neoplasms in the pediatric abdomen. • Describe Doppler findings of pediatric neoplasms. • Differentiate the causes and sonographic findings of congenital hydronephrosis. • Describe the sonographic appearances of pediatric renal cystic diseases. A clinical finding of a palpable mass in a pediatric patient precipitates a search for the origin of the mass. Pediatric abdominal masses commonly arise from the kidney or adrenal gland and less commonly may be associated with a liver, biliary, or gastrointestinal anomaly. Alternatively, a palpable mass may not be directly related to a specific neoplasm but may reflect enlargement of an organ. Organ enlargement may occur with renal cystic diseases and some liver diseases. This chapter focuses on abnormalities of the biliary tract, liver, adrenal gland, and kidneys that occur more commonly in pediatric patients. Anomalies of the gastrointestinal tract and appendicitis are discussed in Chapters 11 and 12. Biliary atresia is the most significant life-threatening hepatobiliary disorder in children and is the most common indication for liver transplantation in pediatric patients.1 Biliary atresia is a serious progressive disease that is the result of narrowing or obliteration of the bile ducts. The different classifications of biliary atresia depend on which portion of the biliary tree is affected. Biliary atresia may affect intrahepatic or extrahepatic ducts and may or may not involve the gallbladder. The most common form of biliary atresia involves the extrahepatic portion of the biliary tree, including the gallbladder. The cause of biliary atresia is unknown, although studies have suggested that biliary atresia may be the result of a congenital maldevelopment of the biliary tree or may be an acquired condition. The association of biliary atresia resulting from a viral infection has also been explored, and hereditary factors have been suggested. Biliary atresia may also be associated with polysplenia syndrome (Fig. 9-2). The clinical features of biliary atresia include persistent jaundice in the neonatal period, acholic stools, dark urine, and enlarged girth from hepatomegaly. If biliary atresia is left untreated, the prognosis is poor; it leads to either liver transplantation or death from complications of liver failure. The commonly accepted treatment for biliary atresia is restitution of the bile flow via hepatoportoenterostomy (Kasai procedure). A successful hepatoportoenterostomy can delay or decrease the need for a liver transplant.1 Outcomes are better with surgery performed at less than 45 to 60 days of life and worse after 90 days of age.2 The triangular cord sign and an abnormal gallbladder in a fasting infant are widely accepted as the diagnostic criteria for biliary atresia.3 The triangular cord sign, which appears as an echogenic area superior to the portal vein bifurcation, represents the obliterated bile duct. A small or absent gallbladder in a fasting infant should be confirmed with postprandial images. Choledochal cyst is a cystic dilation of the biliary tree that most commonly affects the common bile duct (CBD). It is estimated to occur in 1 in 5000 live births, with a higher frequency in Asians.4 Common symptoms include abdominal pain and vomiting, but these are nonspecific making the condition difficult to diagnose during infancy. Jaundice is a more specific symptom, and the diagnosis is usually made early if the jaundice is prolonged during the neonatal period. Five types of choledochal cysts are described using the Todani modification of the Alonso-Lej classification.4,5 Type I is characterized by a fusiform dilation of the CBD and is the most common type. Type II manifests as one or more diverticula of the CBD. Type III, known as a choledochocele, is a dilation of the intraduodenal portion of the CBD. Type IV consists of dilation of intrahepatic and extrahepatic ducts. Type V is classified as Caroli’s disease and manifests with dilation of the intrahepatic ducts. The clinical presentation of choledochal cyst includes jaundice and pain. A palpable mass may also be present. Sonography is useful to differentiate choledochal cyst from other causes of jaundice in infancy, including biliary atresia and hepatitis. Early surgery greatly decreases the occurrence of disease-related complications, such as acute cholangitis, acute pancreatitis, early formation of biliary stone disease, biliary cirrhosis, liver cirrhosis, and malignancy.4 Sonographic investigation of a choledochal cyst most commonly shows fusiform dilation of the CBD (Fig. 9-3), with associated intrahepatic ductal dilation. Depending on the type of choledochal cyst, multiple cysts in the area of the porta hepatis that are separate from the gallbladder may also be identified. Infantile hepatic hemangioendothelioma, also known as infantile hepatic hemangioma, is the third most common hepatic tumor in children, accounting for 12% of all pediatric liver tumors. It is the most common vascular liver tumor of infancy that occurs within the first year of life.6,7 A gender prevalence is seen, with most cases occurring in girls. This condition is a benign tumor, although it can be associated with serious complications, including congestive heart failure resulting from intratumoral high-flow arteriovenous shunts, anemia, thrombocytopenia, jaundice, and bleeding.6 Infants with hemangioendothelioma present with hepatomegaly, which may be accompanied by associated congestive heart failure and cutaneous hemangioma. The serum alpha fetoprotein level is usually within normal range but may be elevated. Because clinical and laboratory findings of infantile hepatic hemangioendothelioma are nonspecific, imaging plays an important role in diagnosis and assessment. Hemangioendothelioma spontaneously regresses by 12 to 18 months of age, but complications may lead to significant morbidity and mortality.6,7 Sonographically, infantile hemangioendotheliomas are well-circumscribed, hypoechoic or hyperechoic masses (Fig. 9-4), which may show flow in vascular structures on Doppler (Fig. 9-5). Extensive arteriovenous shunting can lead to high-output congestive heart failure. Calcifications may be seen in 40% of cases.6,7 Hepatoblastomas are the most common primary liver tumors in young children, with a peak presentation at 1 to 2 years of age and a male-to-female ratio of 2:1. Less frequently, hepatoblastomas may also occur in older children, up to 15 years of age.7 Predisposing conditions include Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome; hemihypertrophy; familial polyposis coli or familial adenomatous polyposis, which can present with its variant known as Gardner’s syndrome; fetal alcohol syndrome; and Wilms’ tumor. It has also been reported to be present more commonly in premature infants and infants with low birth weight. The tumor has a tendency to invade hepatic and portal veins. Clinical findings for hepatoblastoma include palpable abdominal mass, and an elevated serum alpha fetoprotein level may be present in 90% of patients.7 Patients may also have fever, pain, anorexia, and weight loss. The prognosis for this tumor depends on the resectability of the mass. Many patients are in the advanced stages at the time of diagnosis, so the prognosis is poor. Sonographically, hepatoblastomas are solid masses with similar echogenicity compared with surrounding liver parenchyma (Fig. 9-6). The spoke-wheel appearance as a result of fibrous septa is rarely appreciated. Calcification is seen in 55% of cases and may cause acoustic shadowing.7 Additional intralesional necroses or tumor thrombi in the portal vein or hepatic veins may be seen. Adrenal glands in the fetus and neonate are prone to hemorrhage because of their large size and increased vascularity. Adrenal hemorrhage is a common cause of an adrenal mass in neonates and occurs most commonly on the right side but may involve both glands. The list of causes for adrenal hemorrhage is extensive and includes anticoagulation, stress caused by overwhelming sepsis, burns, surgery, hypotension, pregnancy and birth, and exogenous steroids or adrenocorticotropic hormone administration.8,9 Extensive, bilateral adrenal hemorrhage is more common in male infants (male-to-female ratio of 2:1); this probably reflects a male predilection for several of the underlying conditions associated with adrenal hemorrhage.10 Adrenal hemorrhage in healthy infants has been associated with preterm delivery, prolonged labor, breech delivery, large birth weight, infection, birth trauma, or anoxia. There has also been an association with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Signs and symptoms of adrenal hemorrhage are variable and nonspecific. Adrenal hemorrhage may be accompanied by anemia, persistent jaundice, abdominal mass, painful swelling or bluish discoloration of the scrotum, acute adrenal crisis, or shock.8,11 Increased use and sophistication of imaging technology have led to adrenal hemorrhage being diagnosed with increased frequency in hospitalized patients. Distinguishing adrenal hemorrhage from adrenal tumors, such as neuroblastoma, is important because identification of a malignant neoplasm requires surgical intervention, and adrenal hemorrhage usually resolves spontaneously. Adrenal hemorrhage initially appears echogenic and becomes hypoechoic over time. Follow-up sonograms (Fig. 9-7) show involution of the hemorrhage that may resolve to calcification or a residual cyst. Neuroblastoma is a tumor that arises in sympathetic neural crest tissues. It is the most common cancer diagnosed during the first year of life.12,13 Tumors can arise anywhere along the sympathetic nervous system, with most occurring in the adrenal medulla. Other locations include the neck, mediastinum, retroperitoneum, and pelvis. The cause of neuroblastoma is unclear. Studies have been conducted to determine potential risk factors for neuroblastoma, but further investigation is still needed to evaluate potential risk factors, including pregnancy and birth factors, certain environmental exposures, and medications. Heredity is the only known risk factor for neuroblastoma; however, it accounts for only 1% to 2% of all neuroblastomas.13 Diagnosis of neuroblastoma may be made during the perinatal period based on obstetric sonography. The clinical presentation of neuroblastoma depends on the location of the tumor. The postnatal clinical presentation is highly variable, ranging from a mass that causes no symptoms to a primary tumor that causes critical illness as a result of local invasion, widely disseminated disease, or both.12 Infants may have an abdominal mass, hypertension, diarrhea, and bone pain with metastasis. Most patients with neuroblastoma have increased catecholamine levels. The sonographic appearance of neuroblastoma is variable, with small tumors appearing more homogeneous and hyperechoic and large tumors appearing more heterogeneous or complex (Fig. 9-8). Tumors may contain calcifications or may appear cystic. Doppler evaluation may aid in differentiation of neuroblastoma from adrenal hemorrhage because neuroblastoma reveals vascularity within the neoplasm, whereas adrenal hemorrhage does not have flow patterns within the area of hemorrhage.

Pediatric Mass

Biliary Tract

Biliary Atresia

Sonographic Findings

Choledochal Cyst

Sonographic Findings

Liver

Infantile Hemangioendothelioma

Sonographic Findings

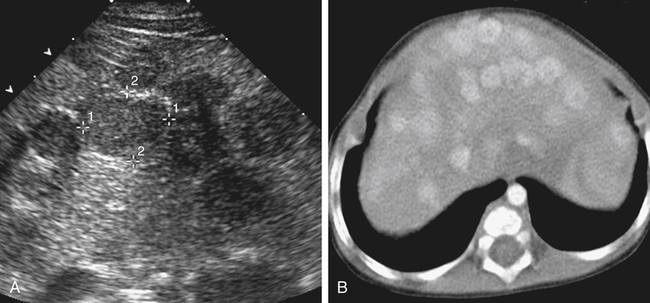

Hepatoblastoma

Sonographic Findings

Adrenal Gland

Hemorrhage

Sonographic Findings

Neuroblastoma

Sonographic Findings

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Pediatric Mass