Pediatrics

David Wilson

Gina Allen

INTRODUCTION

The principal advantages of ultrasound in the examination of children are that it is noninvasive, does not use ionizing radiation, and can be used when motion artifact might degrade alternative imaging techniques in a restless child. Also, the examiner can obtain the clinical history at first hand from the family and child.

EXAMINATION TECHNIQUE

At the outset, it is wise to introduce the child to the equipment, preferably demonstrating its use with the ultrasound jelly on another person, either the examiner or the parent. Involving the child in the process and perhaps allowing them to hold the probe usually helps to obtain cooperation. It helps to show and explain the images on the screen as well as explaining at each stage what movements and positions are required.

High-frequency transducers with a linear array are most often used for musculoskeletal examinations in children. Small footprint “hockey stick” probes are particularly useful provided that they achieve the same nearfield resolution as conventional-shaped probes. Typical frequency ranges are from 5 to 20 MHz, the most useful probes being in the center of this range.

If an interventional procedure is considered likely, informed consent should be obtained from the parent. This is best done in advance. Prior to procedures we ask children under 16 years if they assent to the procedure, as they are under the age of consent. Almost invariably, children agree. As soon as they do, it is important to undertake the procedure with minimal delay. Clear instructions should be given, including warnings that there will be some pain. In practice, if the injection is performed within 30 to 40 seconds of the warning, cooperation usually results. It is wise to ask the parent to sit alongside the child to avoid the risk of the parent experiencing a vasovagal episode.

If it is likely that an aspiration will be undertaken, local anesthetic cream can be applied prior to the procedure.1,2 This takes at least 1 hour to work, ideally 90 minutes. Anesthetic creams are principally based on lignocaine or other short-acting local anesthetics. They should be applied on the area of the intended puncture and placed under an occlusive dressing. Drawbacks include the time to take effect and the occasional skin reaction. Anesthetic injections hurt as much as, if not more than, the puncture for aspiration or injection, and the experienced operator is less likely to cause discomfort when not using local anesthetic injection.

Examination techniques and interpretation in children are identical to those in adults but with the added difficulty that unossified epiphyses and metaphyses show hypoechoic areas that may mimic fluid in the eyes of the unwary. If there is doubt, gentle pressure or comparison with the opposite side will clarify.

In general, examination of children is easier than in adults as children are normally thinner and have better defined tissue planes.

Tip:

Local anesthetic gel should be applied at least 90 minutes before injection.

Unossified bone is hypoechoic.

DEVELOPMENTAL DYSPLASIA OF THE HIP

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) affects approximately one to three per thousand live births, although these figures do not include lesser degrees of dysplasia, which may present as premature adult osteoarthritis. It is possible that the incidence of hip dysplasia is ten to twenty times higher than the recorded incidence.

Factors that increase the risk of developmental dysplasia are:

Family history in a first degree relative

Breech presentation

Female gender

Other congenital abnormalities including ankle and spinal cord defects.

Screening philosophies depend on the local health care environment. In some countries, for example, Germany and Switzerland, all children are examined using diagnostic ultrasound at birth. In others, only those at high risk undergo ultrasound.

Ultrasound examination is more sensitive to abnormalities of the hip, in particular a shallow acetabulum, than clinical examination. Twenty-three percent of children with abnormal ultrasound examinations have normal clinical examination even in the hands of the experienced practitioners.3

In the majority of health care systems, children are examined at birth by an experienced practitioner, and those with any abnormality detected using the Ortolani and Barlow procedures will also be examined using ultrasound.

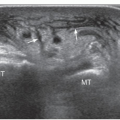

A variety of ultrasound techniques has been proposed. The technique described by Graf is a static examination of the hips in the coronal plane.4 The infant lies in a soft but firm trough in a lateral position with the hips flexed. The ultrasound probe is placed in a coronal plane over the acetabulum and hip. Precise coronal alignment is necessary to ensure that positioning errors do not mimic shallow or deep hips. When the plane is properly achieved, the lateral aspect of the acetabulum is seen as a linear structure. The maximum diameter of the femoral head should also be identifiable on these images.

Static images are analyzed by placing a line along the ilium and a second line along the roof of the acetabulum (Graf alpha angle). The angle described by these two lines can be measured using bespoke software on many ultrasound machines. This roof angle reflects the depth and shape of the acetabulum. A second line drawn along the labrum of the acetabulum describes the cartilage cover and is termed the beta angle. By combining these measurements, Graf creates a numeric classification.

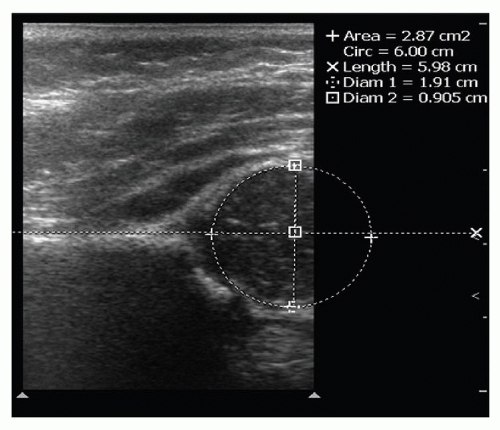

The difficulty with the Graf technique5 is that a roof angle of 42 degrees or greater is regarded as normal, whereas less is abnormal. As it is very difficult to reproduce angles with the precision required to classify patients accurately, the grading may vary between observers.6 Graf described a fairly complex grading system based on the alpha and beta angles.7 An alternative technique described by Terjesen8 is to draw parallel lines along the ilium and at the maximum depth and maximum height of the femoral head. The three lines provide a measurement of how well the femoral head is covered or contained within the acetabulum. Coverage of >55% of the femoral head is normal; 50% or less is regarded as shallow, and <45% is very shallow (Figs. 13.1 and 13.2).

The majority of practitioners assess children in the first few weeks of life when there is an opportunity to treat conservatively with double nappies and splinting. In children younger than 6 weeks with a shallow acetabulum and normally located femoral capital epiphysis, it is reasonable to wait a week or two and then reexamine the hip. In many cases, the acetabulum will have developed and acquired a normal depth. If the depth does not become normal, longer term splintage and potential orthopedic procedures may be considered. The key is to keep the child under review.

Many workers add dynamic assessment.9 Subluxation of the hip during gentle pressure on the hip in an upward and outward direction whilst examining in the coronal plane is regarded as a risk factor. If a shallow hip is clinically normal, firmly located, and cannot be subluxed, many practitioners defer more aggressive forms

of treatment. If the hip is subluxable, early intervention should be considered.

of treatment. If the hip is subluxable, early intervention should be considered.

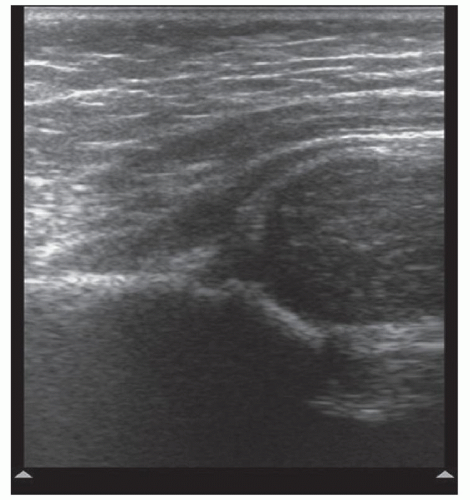

Figure 13.2. Ultrasound of a shallow hip showing mild but significant subluxation. The ball no longer sits in the socket. This worsens under dynamic load. |

Screening processes have considerably reduced the incidence of late presentation. Children normally walk by the age of 1 year, and without screening for hip dysplasia, it may only be at this stage that a dislocation is recognized. Dislocation may present later in childhood subsequent to subluxable and shallow acetabula. Therefore, dislocation at birth is not the hallmark of all children with hip dysplasia problems.

In patients where the hips are relocated surgically, the child is placed in a plaster spica to hold the hip in place. Magnetic resonance (MR) examination is useful in assessing correct relocation.

Tip:

Ultrasound is the technique of choice in assessing for DDH.

IRRITABLE HIP

The majority of children who present with an irritable hip do so between the ages of 3 and 8 years; older children are less likely to develop an irritable hip but are more likely to suffer more serious hip disorders.

Transient Synovitis and Septic Arthritis

The commonest form of irritable hip is transient synovitis, which is of unknown etiology, although a viral origin has been suggested. Children between the ages of 4 and 8 years are most commonly affected. The typical history is of a few hours or perhaps one day of pain and irritability. The child is reluctant to walk or move the hip in any direction, is tearful, and distressed. In most cases, there is a hip joint effusion that varies from 1 to >4 mL. The pain persists while the effusion is present, but as the effusion reduces spontaneously over the next 24 to 48 hours, the pain diminishes. Analgesia is rarely of much benefit. In the past, these children were admitted to hospitals and observed and treated in traction. However, aspiration of the hip in the early stages is not only diagnostic but can rule out rarer causes of acute irritable hip such as septic arthritis or hemarthrosis. At the same time, aspiration alleviates symptoms by relieving pressure on the joint capsule.10,11,12 Transient synovitis is self-limiting. It is a common disorder, and the majority of general hospitals will see several patients a week with this condition. The greatest concern is the much more serious condition of septic arthritis.

Fortunately, septic arthritis is rare, occurring in approximately 1 in every 400 to 500 patients who present with an irritable hip. Septic arthritis can destroy articular cartilage within 12 hours of onset, and therefore early diagnosis is critical. The appropriate treatment is arthrotomy, joint lavage, and intravenous antibiotics, which is more effective than treating with antibiotics alone.

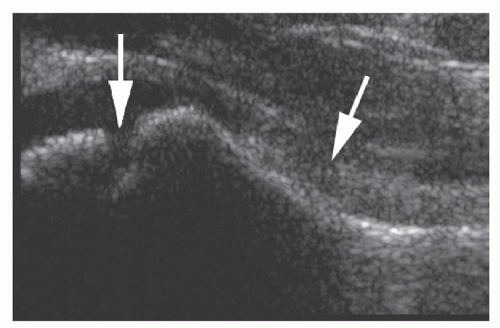

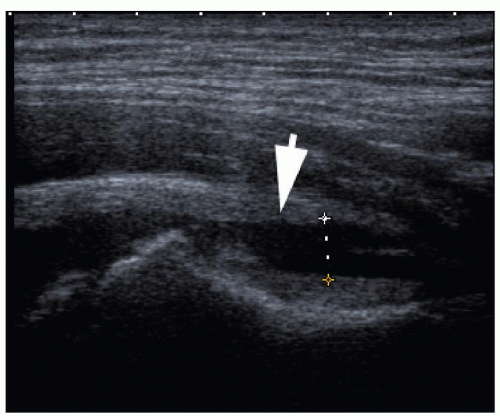

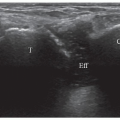

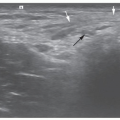

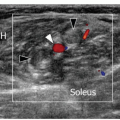

Ultrasound of transient synovitis shows an effusion that elevates the anterior capsule of the joint. Fluid pools anteriorly as the capsule here is thin. The hip is externally rotated as this gives the greatest relaxation of the anterior capsule. An ultrasound probe placed obliquely along the femoral neck best shows the effusion. Deflection of the iliofemoral ligament by >2 mm compared with the normal side is definitely abnormal (Figs. 13.3 and 13.4). It is probable that a difference of 1 mm is sufficient to diagnose a small effusion.13 Septic arthritis presents with exactly the same clinical and ultrasound signs as transient synovitis. Synovial thickening may occur in transient synovitis. Some cases of septic arthritis are not associated with thickening of the synovium. Particulate debris in the joint does not discriminate between

infection and transudate. A hemarthrosis presents with fluid in the joint, and there may be particulate matter and debris, but this is not always the case. Ultrasound demonstration of a joint effusion determines that the hip is the problem and excludes other disorders such as muscle strain, apophyseal injury, and abdominal conditions including retrocecal appendicitis.14 However, the presence and ultrasound appearances of joint fluid do not determine the nature of the effusion, and color Doppler examination does not assist in this discrimination.15 Systemic manifestations of infection are rare in the early stages of septic arthritis. The majority of patients with an acute septic arthritis have normal body temperature, white count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein. Therefore, blood tests do not help triage the children at the onset of symptoms when appropriate therapy for septic arthritis is urgently needed.16,17

infection and transudate. A hemarthrosis presents with fluid in the joint, and there may be particulate matter and debris, but this is not always the case. Ultrasound demonstration of a joint effusion determines that the hip is the problem and excludes other disorders such as muscle strain, apophyseal injury, and abdominal conditions including retrocecal appendicitis.14 However, the presence and ultrasound appearances of joint fluid do not determine the nature of the effusion, and color Doppler examination does not assist in this discrimination.15 Systemic manifestations of infection are rare in the early stages of septic arthritis. The majority of patients with an acute septic arthritis have normal body temperature, white count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein. Therefore, blood tests do not help triage the children at the onset of symptoms when appropriate therapy for septic arthritis is urgently needed.16,17

Ultrasound-guided aspiration of the hip is simple and relatively atraumatic. It provides material for microbiological assessment, including an urgent Gram stain.

The patient should be prepared by placing a local anesthetic jelly patch on the anterior aspect of the hip for at least 1½ hours before the procedure. Informed consent should be obtained from the parents and assent from the child. The needle is placed without any further anesthetic by a direct anterior approach to the femoral neck by marking the transducer position over the fluid on sagittal and transverse scans. The needle is inserted where the scan planes intersect, and any fluid is aspirated. Attempts should be made to aspirate to dry as this will alleviate symptoms. It is exceptionally rare to find any late growth of organisms in cultures if the Gram stain is negative. The majority of patients with septic arthritis have purulent or green fluid. Those patients with septic arthritis go immediately to arthrotomy. Patients with transudates will have had their symptoms relieved and may be discharged. In the vast majority of cases, they recover without further management.10

Recurrent irritable hip with transudates on more than one occasion is an indication for a semi-urgent MR examination as other conditions including osteomyelitis, osteoid osteoma, and neoplasm may mimic recurrent irritable hip, and most are identifiable using MRI. At the upper end of the age spectrum, cases of Perthes disease and even slipped epiphysis may present as an irritable hip. They can be identified by additional imaging. In patients over the age of 8 years, a frog lateral radiograph should be used to exclude slipped epiphysis.

Tip:

A normal ultrasound examination excludes septic arthritis.

Septic arthritis may mimic transient synovitis with normal clinical and laboratory markers.

Diagnostic aspiration to exclude sepsis is also therapeutic for transient synovitis.

Perthes Disease

Perthes disease (Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease) is of unknown etiology. It presents as pain and irritability of the hip and is commonly seen in children aged 8 to 12 years. Perthes typically presents unilaterally but may present subsequently in the opposite hip. If bilateral, changes are usually asymmetric. The conventional radiographic appearances are thickening of the medial joint space due to cartilage edema, not a joint effusion, although an effusion is present in a large proportion of patients. Conventional radiographs later in the disease process show fragmentation of the femoral head, then deformity due to remodeling.

Ultrasound shows a joint effusion in most cases. It may also show fragmentation of the femoral head, but a conventional radiograph is more sensitive in this respect. It has been suggested that the blood supply of the femoral head, largely arising from vessels around the femoral neck, can be assessed using Doppler ultrasound18,19 and that flow around the femoral neck may be an indicator of the integrity of the blood supply to the femoral head. Children with Perthes disease show small arterial caliber and reduced flow in the brachial artery, suggesting that there is a systemic disorder of vessels.18 The role of Doppler ultrasound in Perthes disease is yet to be defined.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree