Howard Richard

Pelvic pain can be divided into acute pain, recurrent pelvic pain, and chronic pelvic pain. Acute pain rarely lasts more than 1 month. It typically resolves of its own accord. Recurrent pain is pain that occurs on a regular basis such as the cyclic pain of dysmenorrhea or the episodic pain of dyspareunia. Chronic pelvic pain is defined as pain located primarily in the pelvis that lasts more than 3 to 6 months.1–3 There are many different causes of chronic pelvic pain, and textbooks have been written delineating the differential diagnosis. It is important to note that although chronic pelvic pain often originates with a biologic underpinning, patients will develop psychological and sociologic components with the passage of time.4 The psychological aspects such as depression and sociologic aspects such as interpersonal relationship dysfunction should be considered in the management of these problems.

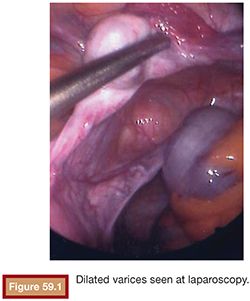

Chronic pelvic pain can be attributed to gynecologic, uterine or extrauterine, urologic, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, or multiple causes. With the discussion of chronic pain based on pelvic venous congestion, we are chiefly concerned about extrauterine gynecologic pain. Richet5 first described pelvic venous varicosities in 1857. Grossly dilated or varicose veins with marked venous incompetence can be noted in women, particularly following pregnancy. Taylor6 reported a connection between the varicosities and pelvic pain in 1949. These varices can extend to the perineal tissues and even to the buttocks and the upper legs.7,8 Dilated ovarian intrauterine vascular plexus can be identified at laparoscopy (Fig. 59.1). This can be challenging secondary to the positive pressure used in laparoscopy. In fact, up to 90% of patients with negative laparoscopy potentially have pelvic congestion syndrome (PCS).9

The clinical features of PCS consist of a deep-seated pelvic pain, classically seen in multiparous women. The pain worsens with prolonged standing or walking and classically improves when in a recumbent position. The patients can have a congestive dysmenorrhea with symptoms worsening before menses. Patients can suffer deep dyspareunia with a postcoital ache, which may last for several days.10,11 This can be accompanied by emotional disturbance such as depression and sociologic turmoil in the patient’s interpersonal relationships.

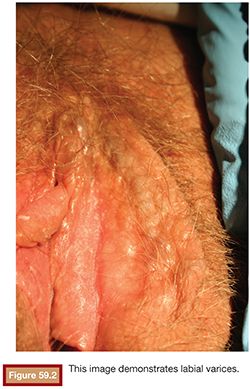

The clinical signs of PCS include external varices involving the external genitalia and superficial vulvar and perivulvar tissue (Fig. 59.2).12,13 Patients may have pain to palpation over the ovarian point, which is two-thirds of the distance from the anterior superior iliac spine to the umbilicus. When evaluating the cervix in these patients, there may be excess clear mucoid discharge. The cervix may be blue secondary to venous engorgement. On bimanual examination, cervical motion tenderness may be found.10,14

Ovarian vein anatomy contributes to the pathogenesis of PCS. In normal patients, ovarian venous return is aided by spontaneous contractility. In some women, the ovarian vein smooth muscle undergoes age-related thinning.15 When this is associated with an increase in venous diameter during pregnancy, the valves are no longer able to function properly. This can result in venous insufficiency. The vascular endothelium is known to contain estrogen receptors, which are related to the trophic response of vascular smooth muscle. In addition, nerves are identified within layers of the veins. The vascular filling and engorgement is also capable of generating pain signals in some patients by releasing pain mediators such as substance P.16 The internal iliac vein can also convey pressure to the periovarian and periuterine vascular plexus. These veins have valves in approximately 10% of patients, and this represents a potential pathway for reflux into the periuterine and periovarian vascular plexus in the event of valvular dysfunction.

Varicose vein development may also be related to genetic structural vein wall anomalies.17 This can be exacerbated by hormonal and hemodynamic factors related to pregnancy. The combination of genetic predisposition and pregnancy can combine to create the environment for the formation of pelvic varicosities. These venous structures can generate pain signals upon distention in some, but not all, women. Therefore, in some patients, the combination of incompetent distended veins with the ability of the veins to generate pain signals with distention results in the syndrome of pelvic venous congestion.

In evaluating patients for the diagnosis of pelvic venous congestion, various imaging modalities have demonstrated dilated veins in asymptomatic women. Ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging scans are able to clearly define dilated ovarian veins. However studies have failed to demonstrate any correlation between the presence of dilated veins and the presence of symptomatic pelvic venous congestion.18–20 On imaging examination, patients with pelvic venous congestion can have polycystic-appearing ovaries. When evaluating patients with PCS and polycystic-appearing ovaries, patients with PCS demonstrate an increased number of a atrophic follicles consistent with follicular atresia.21 This is a distinct difference from patients with polycystic ovary disease and normal patients. Although both patients with pelvic venous congestion and polycystic ovary disease can demonstrate elevated androstenedione content, patients with pelvic congestion demonstrated a decreased response of estradiol to follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) as contrasted with the normal response of estradiol to FSH in patients with polycystic ovary disease and normal patients.22,23

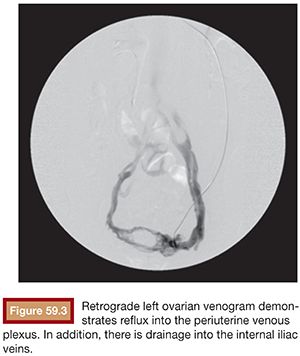

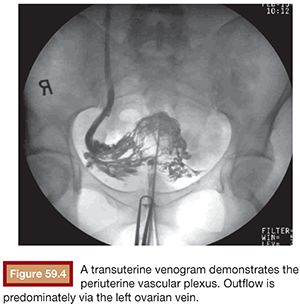

Functional imaging can be performed with catheter venography. Selective catheterization and retrograde venography of the left renal vein only allows visualization of ovarian vein in patients with incompetent valves. However, in some patients, the proximal valve may be competent. Therefore, selective ovarian venography is required to allow passive reflux to extend all the way down the ovarian vein into the pelvic veins. In some patients, the reflux can extend to the perivulvar or upper lower extremity veins. Sometimes, this reflux can be seen extending into the periuterine venous plexus and then ascending in the internal iliac veins (Fig. 59.3). It is possible to perform direct transuterine venography with injection of contrast directly into the uterus (Fig. 59.4). Beard et al.14 first described this technique in the mid-1980s. A grading schema was developed to define the abnormalities on transuterine venography, taking the following factors into account: an ovarian vein diameter greater than 8 mm, a tortuous venous plexus with flow from side to side, and a delay in washout of contrast from the pelvis. The scoring system was devised in which a score of 5 or more gives a diagnostic sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 89% on the diagnosis of pelvic venous congestion syndrome.

Treatment options for pelvic venous congestion syndrome include hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy. This surgery is often used in patients with chronic pelvic pain because some of these patients will have a working diagnosis of adenomyosis, endometriosis, or uterine fibroids. Beard et al.10 reported a study of 36 patients who were diagnosed with PCS and treated with hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy. At 1-year follow-up, 12 of the 36 patients had some residual pain, and 1 patient had no significant change in her pain. Therefore, two-thirds of the patients were cured with removal of uterus and ovaries, which can likely be attributed to ligation of the periuterine periovarian venous plexus. Unfortunately, this also shows us that one-third of the patients had persistent pain despite the surgery. Patients with persistent pelvic venous congestion after hysterectomy may benefit from transvenous embolization.

DEVICE/MATERIAL DESCRIPTION

Venous embolization for PCS can be performed via the internal jugular or femoral venous approach. When the procedure is performed via the internal jugular venous approach, a 6-Fr 55 cm straight vascular sheath is used. This allows for stable access to the inferior vena cava. The left renal vein can be catheterized with a vertebral curve or Cobra catheter (Cook Bloomington, Indiana). Both of these catheters will usually allow access to the left ovarian vein. In some cases, the sheath can be advanced into the left renal vein and a reverse curve catheter such as a Roush inferior mesentric (RIM) (Cook Bloomington, Indiana) can be used to gain access to the left ovarian vein. Catheterization of the right ovarian vein is often accomplished with either an multi purpose B (MPB) (Cook Bloomington, Indiana) curve or a Cobra catheter. Evaluation of the pelvic veins is often accomplished with a Berenstein (Cordis Bridgewater, New Jersey) or vertebral curve catheter.

When the procedure is performed via the femoral venous access, a reverse curve sheath such as the Hopkins curve sheath (Cook Bloomington, Indiana) can be used in the left renal vein. Reverse curve catheters such as Simmons-type catheters (Cook Bloomington, Indiana) can be used to gain access to the right ovarian vein.

Embolization can be performed with a sclerosant slurry. Various sclerosants have been used. Hypertonic saline mix with Gelfoam (Ethicon, Sommerville, New Jersey) slurry, Sotradecol (Angiodynamics Inc., Quensbury, New York), Sotradecol foam, and sodium morrhuate have all been used with success. Typically, this is performed in conjunction with embolization using pushable coils, detachable coils, and vascular plugs. The use of glue as an embolic agent for this indication has been described as well.24

TECHNIQUE

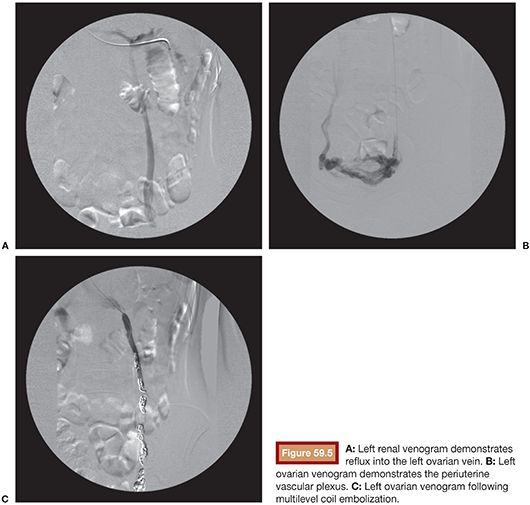

Venous embolization of the ovarian and internal iliac veins is typically performed with intravenous conscious sedation. The internal jugular and or femoral venous access routes can be employed based on operator preference. Left ovarian veins classically arise from the left renal vein (Fig. 59.5). Left renal venography can demonstrate reflux into an incompetent left ovarian vein. However, some patients will have a competent cephalad left ovarian vein valve, and in these patients, selective left ovarian venography is required to confirm the diagnosis of ovarian reflux. Following catheterization of the left ovarian vein, the catheter can be advanced into the pelvis, whereupon venography can demonstrate the periuterine and periovarian venous plexus. Marked stasis of contrast and accumulation and pooling of contrast in the pelvis is consistent with the diagnosis of pelvic venous congestion. Embolization is then performed using a combination of sclerosant slurry and coils or vascular plugs. The embolization is performed at several levels throughout the course of the ovarian vein. This is important because reflux into patent tributaries of the ovarian vein can lead to treatment failure via collateral pathways that circumvent coils placed distally in the target vein. In addition, it is not uncommon to find parallel channels and these should be selectively catheterized and embolized independently.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree