Pelvic Fractures

Visveshwar Baskaran

Traumatic injuries of the pelvis encompass a heterogeneous group of lesions, which vary widely in mechanism. Rapid recognition of bony and soft tissue abnormalities, determination of pelvic stability, and classification of injury pattern is essential in guiding appropriate therapeutic intervention.

Mechanisms.

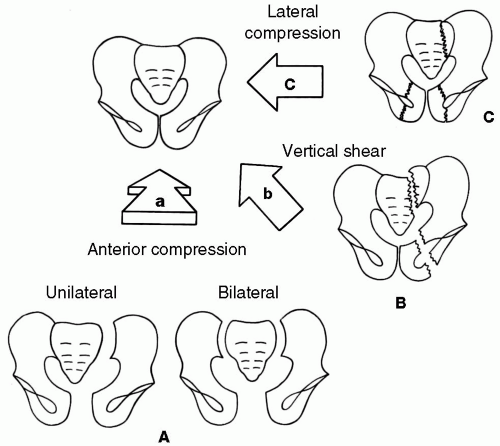

Pelvic fractures resulting from high-energy trauma such as motor vehicle accidents are increasingly common and can result in disruption of the pelvic ring at multiple sites. Earlier classification systems attempted to separate stable injuries from unstable injuries. Recently, classification systems based on mechanism have been advocated, dividing fractures into those due to anteroposterior (AP) compression, lateral compression, or vertical shear (Fig. 45-1). Acetabular fractures often occur with traumatic posterior hip dislocations (i.e., knee striking dashboard) or lateral compression injury, and are divided into elementary or associated fracture types (Fig. 45-2). Isolated pelvic fractures may occur from sports injuries (avulsion or direct pelvic impact). Avulsion fractures result from intense sudden pulling of a tendon on its apophyseal insertion site, such as the anterior superior iliac spine (sartorius), anterior inferior iliac spine (rectus femoris), ischial tuberosity (hamstring muscles), and pubis (adductors). Insufficiency fractures occur in elderly osteoporotic patients, most commonly affecting the pubis and sacral ala.

Symptoms and Signs.

In the setting of acute massive blunt trauma, pelvic ring disruptions should be suspected if the following are present:

Physical examination findings such as lacerations, contusions, evidence of crush injury, or pelvic ring instability on palpation.

Hemodynamic instability from pelvic hemorrhage.

Blood at urethral meatus—genitourinary injury often associated with anterior pelvic fracture.

Pelvic pain.

Gait abnormality.

Neurologic deficits from injury to lumbosacral plexus, most commonly L5 and S1.

Differential Diagnosis.

The major differential diagnosis is soft tissue trauma and hemorrhage without fracture. All of the secondary signs listed in the preceding text may be present even when a fracture is not present.

Indications.

Excellent initial examination before proceeding to computed tomography (CT); identifies nearly all clinically important fractures and dislocations; can be performed while patient is being stabilized.

Protocol.

AP pelvis. Inlet and outlet views (allows identification of subtle pubic or sacral neural foraminal fractures). Coned oblique views of ilium or obturator ring (if suspected

fracture not seen on previous views). Coned AP, lateral, caudad, and cephalad angled views of sacrum (if sacral fracture suspected but not seen on previous views). Coned AP and Judet (right and left posterior oblique) views of acetabulum (if acetabular fracture suspected).

fracture not seen on previous views). Coned AP, lateral, caudad, and cephalad angled views of sacrum (if sacral fracture suspected but not seen on previous views). Coned AP and Judet (right and left posterior oblique) views of acetabulum (if acetabular fracture suspected).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree