Anatomy

The true (lesser) pelvis is divided from the false (greater) pelvis by an oblique plane extending across the pelvic brim from the sacral promontory to the symphysis pubis. The true pelvis contains the rectum, bladder, pelvic ureters, and prostate and seminal vesicles in males, or vagina, uterus, and ovaries in females. The false pelvis is open anteriorly and is bounded laterally by the iliac fossae. It contains small-bowel loops and portions of the ascending colon, descending colon, and sigmoid colon.

Muscle groups form prominent anatomic landmarks on CT. The psoas muscles extend from the lumbar vertebrae through the greater pelvis to join with the iliacus muscles arising from the iliac fossa. The iliopsoas muscles exit the pelvis anteriorly to insert on the lesser trochanters of the femurs. The obturator internus muscles line the interior surface of the lateral walls of the true pelvis. Involvement of these muscles by pelvic tumors generally precludes surgical resection of the tumor. The piriformis muscles arise from the anterior sacrum and exit the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen to insert on the greater trochanter of the femur. The piriformis forms a portion of the lateral wall of the true pelvis. The pelvic diaphragm, composed of the levator ani anteriorly and the coccygeus posteriorly, stretches across the pelvis to separate the pelvic cavity from the perineum. The pelvic diaphragm is penetrated by the rectum, urethra, and vagina.

The pelvis is divided into three major anatomic compartments ( Figs. 18.1 and 18.2 ). It is important to understand these because anatomic compartments allow determination of the origin and spread of disease. The peritoneal cavity extends to the level of the vagina, forming the pouch of Douglas in females, or to the level of the seminal vesicles, forming the rectovesical pouch in males. The extraperitoneal space of the pelvis is continuous with the retroperitoneal space of the abdomen. Pathologic processes from the extraperitoneal space of the pelvis may spread preferentially into the retroperitoneal compartments of the abdomen. The retropubic space (of Retzius) is continuous with the posterior pararenal space and the extraperitoneal fat of the abdominal wall. Fascial planes also allow communication with the scrotum and labia. The presacral space between the sacrum and the rectum normally contains only fat. Any soft-tissue density in this space is abnormal and must be explained. The perineum lies below the pelvic diaphragm. On CT the most obvious portion of the perineum is the ischiorectal fossa. This fossa is seen as a triangular area of fat density extending between the obturator internus laterally, the gluteus maximus posteriorly, and the anus and urogenital region medially.

The arteries and veins define the location of the major lymphatic node chains in the pelvis ( Fig. 18.3 ). The aorta and inferior vena cava divide to form the common iliac vessels at the level of the top of the iliac crest. The common iliac vessels divide at the pelvic brim, marked on CT by the transition between the convex sacral promontory and the concave sacral cavity. The internal iliac (hypogastric) vessels course posteriorly across the sciatic foramen, dividing rapidly into smaller branches. The external iliac vessels course anteriorly adjacent to the iliopsoas to exit the pelvis at the inguinal ligament. Pelvic lymph nodes are classified with their accompanying vessels and are correspondingly named the common iliac , internal iliac , and external iliac nodal chains . The obturator nodes are satellites of the external iliac chain and course along the midportion of the obturator internus. Inguinal nodes in the subcutaneous tissue near the common femoral vessels drain the perineum but not the true pelvis. Pelvic lymph nodes are considered pathologically enlarged on CT when they exceed 10 mm in short axis.

The bladder is best appreciated on CT when filled with urine or contrast agent. The normal bladder wall does not exceed 5 mm in thickness when the bladder is distended. The dome of the bladder is covered by peritoneum, whereas its base and anterior surface are extraperitoneal. The ureters course anterior to the psoas, cross over the common iliac vessels at the pelvic brim, pass on either side of the cervix, and insert into the bladder trigone. In males the ureters insert into the bladder just above the prostate at the level of the seminal vesicle.

The vagina is seen in cross section as a flattened ellipse of soft tissue between the bladder and rectum. An inserted tampon will outline the cavity of the vagina with air density and is useful in marking the vagina for pelvic CT. The level of the cervix is recognized by the transition from the elliptic shape of the vagina to the rounded shape of the cervix. Contrast-filled ureters are frequently identified in close proximity to the cervix. The uterus is seen as a homogeneous, smooth-outlined oval of soft-tissue density. The myometrium is highly vascular, causing the uterus to enhance more than most pelvic organs. Assessment of the uterus on CT is made difficult by variation in the position and flexion of the uterus and the amount of bladder filling. The broad ligament is a sheetlike fold of peritoneum that drapes over the uterus and extends laterally to the pelvic sidewalls. Between the leaves of the broad ligament is the parametrium , which is loose connective tissue and fat through which pass the fallopian tubes, uterine and ovarian blood vessels and lymphatics, the pelvic ureters, and the round ligament. Determination of tumor extension into the parametrium is an important part of gynecologic tumor staging. The fallopian tube forms the superior free edge of the broad ligament, best seen when outlined by ascites. The fallopian tube with its covering broad ligament is rather like a sheet folded over a clothes line with the parametrium between the folds of the sheet. The cardinal ligaments extend laterally from the cervix to the obturator internus muscles, forming the base of the broad ligament. The cardinal ligaments appear on CT as triangular densities extending laterally from the cervix. The round ligaments extend from the uterine fundus through the internal inguinal ring to terminate in the labia majora. Uterosacral ligaments extend in an arc from the cervix to the anterior sacrum. Uterine arteries branch from the hypogastric trunk and course in the parametrium just superior to the cardinal ligaments. Enhanced parametrial blood vessels are commonly prominent on contrast-enhanced CT scans obtained with bolus contrast medium administration. Normal ovaries are sometimes difficult to identify on CT. Because they are mobile, they may be anywhere in the pelvis, but they are most commonly seen adjacent to the uterine fundus. They appear as oval soft-tissue densities, approximately 2 × 3 × 4 cm. The presence of cystic follicles allows positive identification of the ovaries.

The normal prostate gland is seen at the base of the bladder as a homogeneous, rounded soft-tissue organ up to 4 cm in maximal diameter. Prostate zonal anatomy, well shown by magnetic resonance imaging, is not demonstrated by CT. A well-defined plane of fat separates the prostate from the obturator internus. This fat plane may be invaded by carcinoma. Denonvilliers fascia provides a particularly tough barrier between the prostate and the rectum, usually preventing spread of tumors from one organ to the other. The paired seminal vesicles produce a characteristic bow tie–shaped soft-tissue structure in the groove between the bladder base and the prostate. Normal testes are easily identified in the scrotum as homogeneous oval structures 3 to 4 cm in diameter. The spermatic cord can be recognized in the inguinal canal as a thin-walled oval structure of fat density containing small dots representing the vas deferens and spermatic vessels.

Technical Considerations

The ideal technique for CT of the pelvis requires optimal bowel opacification. A typical procedure involves the giving of 500 mL of dilute contrast agent orally the evening before the examination and a repeated dose 45 to 60 minutes before the examination. The colon and rectum can be distended by placement of a tube in the rectum and insufflation with 20 puffs of air, or to the limit of patient comfort. Patients are asked to avoid urination for 30 to 40 minutes before the examination to allow bladder filling. Intravenous contrast medium is routinely given by a mechanical injector at 2 to 3 mL per second for a total dose of 150 mL of 60% contrast agent. CT images through the pelvis are viewed as contiguous 2.5- to 5-mm-thick slices. The abdomen should also be in patients with known or suspected pelvic malignancy. To optimize contrast enhancement of pelvic organs, the pelvis can be scanned first, then the abdomen. Coronal and sagittal plane reconstructions are often helpful.

Bladder

Bladder Carcinoma

Bladder cancer may be superficial and confined to the mucosa. However, with invasion of the bladder wall musculature, the risk of spread to regional and distant nodes increases. As the number and size of nodal metastases increases, so does the risk of hematogenous spread to bone and lung. CT is useful for the staging of advanced disease but is not accurate in defining early-stage disease. Patients are generally referred for CT staging after muscle invasive disease is suspected on cystoscopy. The key elements of staging are the depth of tumor invasion into the bladder wall and the involvement of adjacent and distant sites by tumor. Most malignant bladder tumors (95%) are uroepithelial (transitional cell) carcinomas that carry a risk of multiple synchronous tumors in the ipsilateral ureter and renal collecting system. Squamous cell carcinomas (4%–5%) are usually associated with chronic inflammation. Adenocarcinomas account for less than 2% of bladder tumors. The CT findings are as follows:

- •

The primary tumor appears as a focal thickening of the bladder wall or as a soft-tissue mass projecting into the bladder lumen ( Fig. 18.4 ). Early postcontrast scans may demonstrate a weakly enhancing mural nodule on a background of low-attenuation urine. Delayed scans show a soft-tissue filling defect on a background of high-attenuation contrast-opacified urine. Masses may be plaque-like, polypoid, or papillary.

FIG. 18.4

Transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: polypoid.

Bone windows provide the best visualization of a polypoid frond-like mass (arrowhead) projecting into the bladder lumen and seen as a filling defect within the intraluminal contrast material layering within the bladder.

- •

Multicentric tumors occur in 30% to 40% of cases, with tumors in the upper tracts in 2% to 5% of cases. One should always look for additional tumors.

- •

The bladder must be well distended or subtle tumors, especially small flat lesions, can easily be overlooked. Bladder tumors enhance maximally at 60 seconds after contrast medium injection, stressing the need to scan the pelvis during this time frame.

- •

Calcifications are seen in 5% of transitional cell carcinomas

- •

Perivesical spread is seen as soft-tissue density in the perivesical fat ( Fig. 18.5 ). Extension to the pelvic sidewall musculature precludes complete surgical resection.

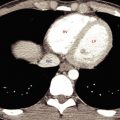

FIG. 18.5

Transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: wall thickening.

Spreading tumor (red arrowheads) thickens the bladder wall and projects into the bladder lumen (B) near the trigone. Tiny nodules and strand-like densities (yellow arrow) infiltrate the normally clear fat triangle between the bladder and the seminal vesicles (SV) . In this case the tumor penetrated the bladder wall and infiltrated the perivesical fat; however, this finding is not always a reliable indication of tumor spread. The obturator internus muscles (green arrows) are clearly not involved, indicating that this tumor is potentially resectable. Clear fat separates these muscles from the perivesical tumor nodules. R , Rectum.

- •

Pelvic lymph nodes larger than 10 mm in short axis are considered positive for metastatic disease. Smaller nodes are unlikely to be involved.

- •

Hematogenous metastases are most common in the liver, lungs, bones, and adrenal glands.

- •

Rare bladder tumors to be considered in the differential diagnosis include pheochromocytoma, leiomyoma, lymphoma ( Fig. 18.6 ), sarcoma, and metastases.

FIG. 18.6

Lymphoma of the bladder.

Lymphoma (arrowheads) causes nodular thickening extending into the bladder lumen (B) mimicking transitional cell carcinoma. Ascites (a) is present, distending the rectovesical pouch of Douglas. R , Rectum.

Bladder Diverticulum

Bladder diverticula are seen as a cystic pelvic mass. Identification of communication with the bladder lumen is the key to correct diagnosis ( Fig. 18.7 ). Bladder diverticula provide a site for urine stasis, which commonly results in stone formation and recurrent infection.

Cystitis

Cystitis refers to inflammation of the bladder wall. It is a common condition affecting patients of all ages. It is most common in women.

- •

Acute bacterial cystitis is most common and usually caused by Escherichia coli infection. The diagnosis is made clinically, and imaging is usually not required. Bullous mucosal edema may thicken the bladder wall and give it a cobblestone appearance. Chronic cystitis usually related to poor bladder emptying caused by neurogenic bladder or chronic bladder outlet obstruction may result in a fibrotic contracted bladder with a thick wall ( Fig. 18.8 ).

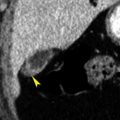

FIG. 18.8

Chronic cystitis.

CT in the axial plane without intravenous contrast medium shows the bladder (B) to be contracted and thick walled in a paraplegic patient with neurogenic bladder and chronic cystitis. The ureters (yellow arrowheads) are seen entering the bladder. Inflammatory stranding (red arrow) extends into the pericystic fat. R , Rectum; SV , seminal vesicles.

- •

Cystitis cystica and cystitis glandularis are inflammatory disorders that result from chronic irritation of the bladder wall caused by recurrent bacterial cystitis or bladder stones. CT shows multiple hypervascular enhancing polypoid masses of variable size.

- •

Interstitial cystitis is an uncommon idiopathic disease characterized by fibrosis of the bladder wall. Bladder volume is restricted, and the bladder wall ultimately becomes thinned.

- •

Emphysematous cystitis refers to the presence of gas in the bladder wall and lumen caused by bacterial infection in glucose-laden urine. The disease occurs in patients with diabetes mellitus who have bladder dysfunction related to neurogenic bladder, bladder diverticula, or chronic bladder outlet obstruction. CT shows thickening and streaks and bubbles of gas in the bladder wall ( Fig. 18.9 ). Gas in the bladder lumen forms air-fluid levels.

FIG. 18.9

Emphysematous cystitis.

Gas (arrowheads) is present in the wall of the bladder in this diabetic patient with urinary sepsis.

- •

Tuberculosis of the bladder is an extension of renal tuberculosis. CT findings in the acute stage include bladder wall thickening, trabeculation, and irregular mucosal masses representing tubercles. In the chronic stage the bladder becomes contracted and the wall is commonly calcified.

- •

Schistosomiasis is caused by infestation with the parasite Schistosoma haematobium , which is most commonly found in Africa. Eggs laid in the bladder wall produce nodular wall thickening in the acute phase and result in a fibrotic contracted bladder with wall and distal ureteral calcification in the chronic phase.

Bladder Stones

Bladder stones are much less common than kidney stones. Bladder stones may form primarily within the bladder, from foreign bodies within the bladder, or from kidney stones that are retained within the bladder. Most occur in the setting of urinary stasis within the bladder caused by neurogenic bladder, an enlarged prostate, recurrent urinary infections, or a bladder diverticulum.

- •

CT is sensitive for detection of even very small stones in the bladder. Stones appear as foci of high attenuation ( Fig. 18.10 ).

FIG. 18.10

Bladder stones.

Three calculi (red arrowhead) are seen as oval high-attenuation masses within the bladder lumen. Numerous phleboliths (yellow arrow) are present in the pelvis, seen as high-attenuation foci within thrombosed veins.

Uterus

Leiomyoma

Leiomyomas (fibroids) are found in up to 40% of women older than 30 years. As frequent findings, their CT features should be recognized.

- •

Leiomyomas appear as homogeneous or heterogeneous masses that may be hypodense, isodense, or hyperdense relative to enhanced myometrium ( Fig. 18.11 ). Diffuse enlargement of the uterus and lobulation of its contour are common ( Fig. 18.11B ).

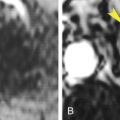

FIG. 18.11

Leiomyoma uterus.

(A) Axial CT shows a large leiomyoma (between red arrowheads ) extending anteriorly from the uterus (U) . (B) Axial postcontrast CT image of another patient showing multiple leiomyomas (red arrowheads) enlarging the uterus and deforming its contour. The left ovary (yellow arrow) contains a physiologic cyst. (C) Sagittal CT image demonstrating the coarse “popcorn” calcification (arrow) characteristic of degenerated leiomyomas. (D) Axial postcontrast CT shows a large heterogeneous leiomyoma (between red arrows ) with areas that are clearly of fat attenuation (yellow arrow) . Compare this with adjacent pelvic fat. This finding is characteristic of lipoleiomyoma.

- •

Coarse dystrophic mottled calcifications within the mass are common and characteristic ( Fig. 18.11C ).

- •

Cystic degeneration produces interior low density and may convert the mass into a large cavity.

- •

Pedunculated leiomyomas may appear as adnexal masses rather than uterine masses. Parasitic leiomyomas are separate from the uterus, having undergone torsion and detached from the uterine pedicle and implanted on the peritoneum.

- •

Lipoleiomyomas are variant tumors consisting of smooth muscle, fibrous tissue, and mature fat. CT shows foci of fat attenuation (below –30 Hounsfield units) within the tumor ( Fig. 18.11D ).

- •

Rare leiomyosarcomas cannot be accurately differentiated from leiomyomas by CT appearance alone. Rapid growth of a uterine mass in a postmenopausal woman suggests malignancy. Leiomyosarcomas appear as large masses with prominent irregular low-attenuation areas of necrosis and hemorrhage ( Fig. 18.12 ). The appearance of leiomyosarcoma overlaps that of benign leiomyoma with extensive degeneration.

FIG. 18.12

Leiomyosarcoma uterus.

Postcontrast CT image in the sagittal plane showing a large heterogeneous hemorrhagic tumor (red arrows) arising from the lower uterine segment and invading the cervix and vagina. The tumor mass presents at the introitus (yellow arrowhead) . The posterior wall of the bladder (B) is invaded by tumor (red arrowhead) . The bladder contains air from previous catheterization. U , Fundus of the uterus.

Carcinoma of the Cervix

Although CT has been used to stage cervical carcinoma, MRI is preferable in most instances. CT is useful to stage advanced disease and to detect recurrence. Unsuspected cervical cancers may also be detected by CT performed for other indications. Cervical malignancies are squamous cell carcinomas (85%) and adenocarcinomas (15%) that spread primarily by direct extension to adjacent organs and tissues. Lymphatic spread to regional nodes is common. Hematogenous spread to lung, bone, and brain is uncommon and occurs late in the course of disease. The accuracy of CT staging is in the range of 65%, compared with 90% reported for MRI. The CT findings include the following:

- •

The normal cervix enhances variably on early postcontrast scans but is uniformly enhanced on scans obtained with several minutes’ delay. The primary tumor may be of low attenuation (50%) or isoattenuating (50%) compared with normal cervix ( Fig. 18.13 ). Low attenuation is caused by reduced vascularity, necrosis, or ulceration. The primary tumor may enlarge the cervix (>3.5 cm diameter).