2St Georges Hospital, London, UK

3The Regional Medical Center, Orangeburg, SC, USA

4The London Independent Hospital, London, UK

- Pelvic fractures in major trauma may be life-threatening (NB suspect vascular and pelvic organ injuries in these patients)

- If one fracture is detected, always look for a second one

- Hip fractures may occur after minor trauma in elderly patients

- Plain radiographs are difficult to interpret and provide limited information. There should be a low threshold for use of CT and MRI

Pelvic and hip fractures are seen in the elderly population with trivial trauma whilst the mechanism in young patients generally involves high-impact injuries including road traffic accidents (RTAs). There is high morbidity and mortality associated with pelvic fractures. This results from internal visceral injuries (commonly bladder and urethra and rarely uterus, cervix, vagina and rectum) and bleeding due to high impact in RTAs, falls in young patients and associated underlying co-morbidities in elderly population. Prognosis is poor if the injuries are not detected and treated promptly. Pelvic fractures can be open or closed. The mortality rate for closed pelvic fractures is 27% and that for open fractures is 55%.

In contrast, hip fractures may occur after relatively minor trauma in elderly patients and are suspected from the clinical history and examination. The fractures may be subtle on plain radiographs and may be overlooked in particular in obese and elderly osteopenic patients.

Anatomy

Bony anatomy

Pelvis

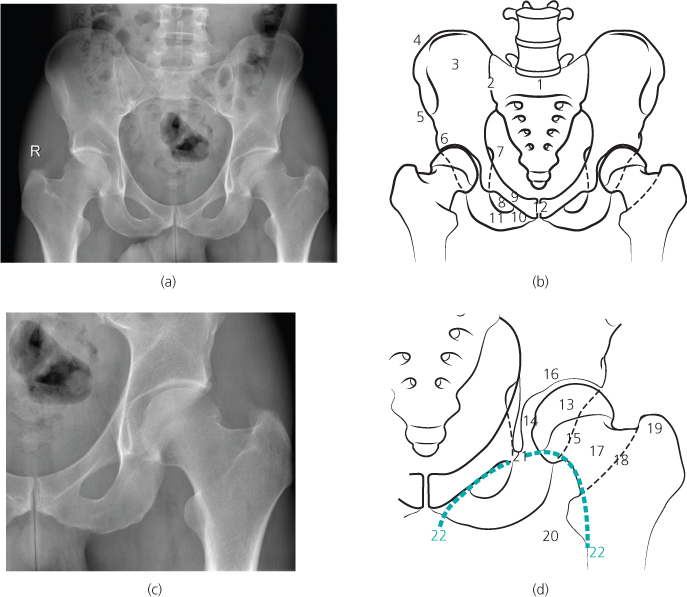

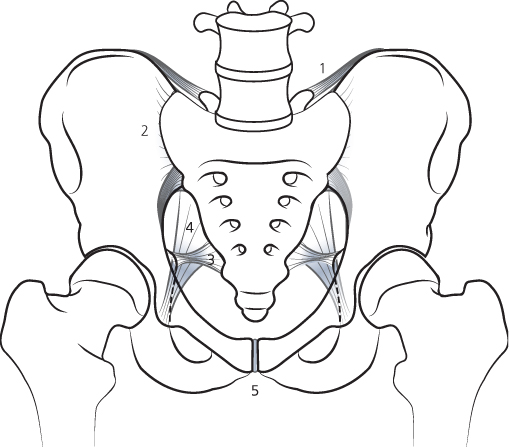

The pelvis is the connection between lower limb and trunk and hence it is inherently unstable. It comprises three separate bones (the sacrum and two iliac/innominate bones) which are held together by a series of strong ligaments. The integrity of this pelvic bony ring can be compromised by disruption of these ligaments (Figures 5.1 and 5.2).

The ligaments are the anterior and posterior sacroiliac ligaments, the sacrotuberous ligament, sacrospinous ligaments and the ligaments of the symphysis pubis. The posterior group is strong and complex and attaches the spine to the pelvis. They resist posterior deformation. The anterior group in contrast is weak and prevents distraction and anteroposterior displacement. The anterior ligaments are the first to disrupt.

Figure 5.1 (a)–(d) Normal pelvic and hip anatomy: 1, sacrum; 2, sacro-iliac joint; 3, ilium; 4, iliac crest; 5, anterior superior iliac spine; 6, anterior inferior iliac spine; 7, ischial spine; 8, obturator foramen; 9, superior pubic ramus; 10, inferior pubic ramus; 11, ischial tuberosity; 12, symphysis pubis; 13, femoral head; 14, fovea centralis; 15, posterior acetabular rim; 16, acetabulum; 17, neck of femur; 18, inter-trochanteric line; 19, greater trochanter; 20, lesser trochanter; 21, Kohler’s tear drop; 22, Shenton’s line.

Hip

The femoral head and the acetabulum form the hip joint. The acetabulum is formed by the anterior and posterior columns and connected by the supra-acetabular region. The anterior and posterior columns are connected to the axial skeleton through the sciatic buttress. Hip fractures are not commonly associated with dislocations because of the strong joint capsule. Hip fractures may be associated with avascular necrosis of the femoral head. This is more commonly seen in intracapsular rather than extracapsular fractures. There are various muscle attachments around the pelvis and hip region, which may be avulsed in traction injuries.

In children, the proximal capital femoral epiphysis is present from the age of 3 months until 18–20 years. There can be asymmetry of the epiphysis with irregularity and notching, which can be a normal finding. However, flattening is generally considered abnormal.

ABCs systematic assessment

- Adequacy

- Alignment

- Bone

- Cartilage and joints

- Soft tissues

Pelvis

Standard

- AP view of hips

- Lateral

Additional

- Oblique view

- Inlet view

- Outlet view

Hip

Standard

- AP view of both hips

Additional

- Frog leg lateral view

Pelvis

Plain X-rays

Adequacy

The routine view is a single AP view of the pelvis. The x-ray is generally done along with the AP CXR in the trauma protocol series. It is difficult to assess the stability of the pelvis on the AP view. In a comparative study between MDCT and plain X ray of the patients with blunt trauma, CT demonstrated 629 fractures in contrast to 405 fractures in a total of 226 patients. This gives an overall sensitivity of only 55% stressing the importance of pelvic CT in evaluation of patients with pelvic trauma.

Ideally the AP view has to cover the pelvis from the level of the iliac crests to the ischial tuberosity and laterally to include both greater trochanters.

Penetration should be adequate and is assessed by looking at the soft tissue structures. The soft tissue shadows which should be seen include the bladder with its perivesical fat, iliopsoas shadows and the rectum and bowel gas. It is important to note that the adequacy criteria may be difficult to meet due to reasons mentioned earlier. In addition elderly patients may have a large belly with thin proximal thighs and hence the exposure may vary significantly. The pelvic AP view is generally considered sensitive for the anteroinferior part of the pelvis, reasonable in the region of the acetabulum and Ilium and poor in the region of the posterior ring.

Pelvic centring also needs to be assessed. This can be done by aligning the symphysis with the sacrum and checking for the symmetry of the obturator foramina.

The AP view of the pelvis gives important information about the initial assessment of the traumatised patient so as to assess for other more significant underlying injuries. These significant injuries may be fractures of the acetabulum, obturator ring, injury to the bladder and urethra.

The AP view can be supplemented by inlet and outlet views of the pelvis in addition to the oblique (Judet) views especially in cases of suspected acetabular injury. However, nowadays these views have been replaced by CT with MPR and 3D reconstructions.

Alignment and bones

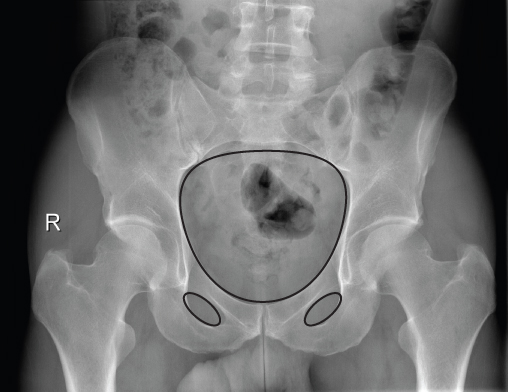

The bony alignment is assessed by dividing the pelvis into three circles, one large circle and two smaller circles (Figure 5.3). The larger circle is the pelvic brim whilst the smaller circles are made by the obturator rings. The larger circle of the pelvic brim should be visualised as a continuous line around the margins of the brim and continuing across the sacroiliac joints (SIJs) posteriorly and symphysis pubis anteriorly.

Figure 5.2 Normal pelvic ligamentous anatomy: 1, left posterior sacro-iliac ligament; 2, right anterior sacro-iliac ligament; 3, right sacrospinous ligament; 4, sacrotuberus ligament; 5, symphysis pubis.

Figure 5.3 Normal three bony pelvic rings.

If a fracture is detected, always check for a second fracture or disruption/diastasis in the same ring (imagine trying to break a polo mint in one place!).

The smaller rings are formed by the two obturator foramina. (The same rule applies to the obturator foramina, if a fracture is detected, there is almost always a second fracture in the same ring or diastasis of the pubic symphysis.) There is a smooth uniform arc formed by drawing a line along the inner margin of the femoral neck and extending continuously to the superior margin of the obturator foramen. This continuous line is called Shenton’s line. Disruption of this line indicates a femoral neck fracture. The only exception to this is if the fracture is non-displaced.

There are certain other important lines, which can be assessed. These include the iliopectineal line, which assesses the anterior column, the ilioischial line, which assesses the posterior column, the anterior acetabular line and the posterior acetabular line. The latter two form the anterior and posterior margins of the acetabulum respectively. The teardrop line is seen at the medial margin of the acetabulum and hip joint, which indicates damage to the medial wall of the acetabulum.

In addition it is vital to follow the lines of the sacral foramina as a discontinuity of the sacral foramina line indicates a fracture, which can involve the sacral nerve roots.

Avulsion injuries tend to occur at the site of the attachment of the strong anterior and posterior hip and thigh muscles. The sites to look for avulsion injuries are the ischial tuberosity for hamstring tendons, anterior inferior iliac spine for rectus femoris muscle, anterior superior iliac crest for the sartorial muscle and also the sacral spines for sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments.

In children, the pubis, ischium and ilium remain separated by a Y-shaped cartilage (called the triradiate cartilage) which fuses in puberty to form the acetabulum. In addition, there are other small accessory ossification centres, which should not be mistaken for fractures.

Cartilage and joints

The pubic symphysis is well visualised and should be checked for alignment, widening, asymmetry or overlapping bones. The symphysis pubis shows widening of the joint space in AP compression injuries. In vertical shear or injury to the pelvis from a fall, superior displacement of the symphysis can be seen.

The anterior margins of the SIJs are well visualised and should be checked for alignment, widening, asymmetry and overlapping. These changes tend to be more subtle and can be easily overlooked, in particular as there is often overlying bowel gas.

Soft tissues

Check for loss or displacement of soft tissue outlines, in particular displacement or asymmetry of the perivesical fat plane (surrounding the bladder) or the obturator internus fat plane (medial edge of the obturator internus muscle), which are strongly suggestive of a pelvic sidewall haematoma secondary to a fracture.

Computed tomography (CT)

In major trauma, the pelvic CT is covered as part of the whole body CT protocol. However, if a CT has not been performed, then pelvic CT should be carried out with intravenous contrast enhancement and is viewed on soft tissue and bone algorithm windows, in addition to MPR and 3D. CT angiography (CTA) should also be performed to look for vascular injuries. CT cystography (contrast is instilled into the bladder) can be performed to look for and assess bladder injuries.

MPRs and 3D reconstructions give detailed characterisation of simple and complex pelvic fractures and are now considered essential for preoperative planning for major pelvic reconstructions.

CT is also used to exclude and to assess injuries to the pelvic organs including the bladder, urethra, rectum, uterus and the cervix and vagina. Pelvic haematomas can be detected and active contrast extravasation at the time of the CT, indicates active ongoing bleeding.

Patterns of injury to the pelvis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree