Key Points

- •

Ultrasound-guided single-injection nerve blocks can be a primary or adjunctive tool to reduce pain from acute injuries or uncomfortable procedures.

- •

Targeted deposition of local anesthetic near specific nerves has been shown to be effective outside of the operating room and is an ideal technique in a multimodal approach to pain management.

- •

An ultrasound-guided femoral nerve block can effectively reduce pain from acute hip fractures.

Background

Alleviating pain is one of the basic tenets of medical care, and newer methods continue to emerge as part of a multimodal approach to pain management. A recent Cochrane review of peripheral nerve blocks revealed that ultrasound guidance in the hands of anesthesiologists is an efficacious technique for surgical anesthesia. Ultrasound-guidance reduces time of nerve block onset and volume of anesthetic required compared to classic nerve stimulation and landmark-based methods. Ultrasound-guided nerve blocks for pain reduction allow providers to reduce the amount of adjunctive analgesic therapy, in particular intravenous opioids needed, thereby reducing undesired dose-related side effects, such as respiratory depression. This chapter focuses on three commonly performed nerve blocks that can be incorporated into clinical practice with the underlying goal to improve patient analgesia.

Indications

Single-injection ultrasound-guided nerve blocks are ideal to relieve pain from acute injuries and painful procedures. Common indications include wound debridement and irrigation, laceration repair, incision and drainage, fracture reduction, and joint relocation. Depending on the effectiveness of a nerve block, adjunctive therapies can be added to maximize patient comfort during painful procedures.

Patient Selection

Single-injection ultrasound-guided nerve blocks should be performed only in patients who are awake, alert, and able to cooperate with a neurologic exam. Patients with preexisting neurologic deficits are not candidates for ultrasound-guided nerve blocks because the presence of peripheral nerve injury (PNI) postprocedure, even though rare, is difficult to evaluate. Caution is recommended in injuries that are at high risk for compartment syndrome (e.g., distal tibia fractures, crush injuries). Although data are limited that ultrasound-guided nerve blocks may mask an evolving compartment syndrome, we recommend consulting the primary surgical service (e.g., trauma surgery, orthopedics) to assess the risks and benefits before a block is performed in patients at risk for compartment syndrome.

Peripheral Nerve Injury

PNI is an uncommon event defined as persistent motor or sensory deficit or pain after a nerve block; its incidence ranges from 0.5% to 2.4%. The mechanism of injury is not well understood; direct needle trauma from the needle, increased intrafascicular pressures from the anesthetic, direct cytotoxic effects of the anesthetic, and nerve ischemia secondary to the metabolic stress of the anesthetic have been proposed. For these reasons, we recommend three intuitive steps to reduce the risk of PNI. First, place the needle tip close to, but not in, the nerve fascicle. Second, slow low-pressure injections should be performed, stopping the procedure if the patient experiences any new pain or paresthesias. Finally, we recommend not performing an ultrasound-guided nerve block in patients with underlying peripheral neuropathy.

Positioning

The ultrasound system is generally positioned in front of the provider, opposite from the procedure site ( Figure 34.1 ). To improve ergonomics, the ultrasound screen should be positioned in the provider’s direct line of site, allowing visualization of both the needle and ultrasound screen without significant head turning. All nerve blocks should be performed with the patient on a cardiac monitor with continuous pulse oximetry.

Supplies

Skin overlying the injection site should be sterilized with chlorhexadine or an equivalent solution. A small-gauge needle (25–30G) can be used to anesthetize the skin at the site of injection. The ultrasound transducer should be covered with a transparent, adhesive dressing or a sterile transducer cover. Selection of needle gauge and length depends on the specific block. A control syringe is preferred ( Figure 34.2 ). Block-specific needles with blunt tips can be used but are not necessary to perform peripheral nerve blocks.

Anesthetic Agent

Lidocaine is preferred over bupivacaine for novice providers. Inadvertent vascular deposition of anesthetic can occur even with meticulous methods. Bupivacaine is known to be toxic to the heart and central nervous system. We recommend that providers who are not very comfortable with the subtle nuances of needle tip visualization only use lidocaine with or without epinephrine. Even with lidocaine’s shorter half-life and increased safety profile, providers should be familiar with the signs and symptoms of Local Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity (LAST). Classically, the patient complains of tongue numbness and lightheadedness, which then progresses to muscle twitching, unconsciousness, seizures, and cardiovascular depression. In cases where bupivacaine has been inadvertently injected into the vascular system, use of a hyperlipophilic solution (20% Intralipid; 1.5 mg/kg bolus with continued infusion of 0.25 mL/min) should be infused. Providers who perform ultrasound-guided nerve blocks should have ready access to 20% Intralipid or similar solution. Standard safety techniques mandate that providers never inject without visualizing the needle tip and always aspirate before injecting to confirm lack of vascular puncture.

Identification of Nerves

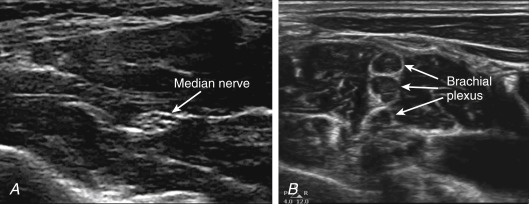

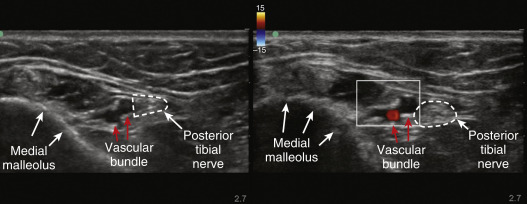

Locating peripheral nerves with ultrasound requires knowledge of adjacent anatomy. Nerves are best visualized and targeted for blocks when oriented in cross section. Distal peripheral nerves appear as bundles of hyperechoic circles or “cluster of grapes” ( Figure 34.3 A ). However, proximal peripheral nerves, such as the roots of the brachial plexus, appear as individual anechoic circles that can easily be mistaken for blood vessels ( Figure 34.3 B). Subtle fanning of the transducer may be necessary to obtain the highest quality images and minimize effects of anisotropy (ultrasound image quality of nerves is more sensitive than many other structures to the angle of ultrasound transmission). Novice providers should verify with color flow Doppler that the intended target is not a vessel ( Figure 34.4 ). For single-injection ultrasound-guided nerve blocks discussed in this chapter, a high-frequency linear transducer (6–13 MHz) is needed. To maintain image orientation during ultrasound-guided peripheral nerve blocks, the transducer’s orientation marker is pointed toward a supine patient’s right side or head.

Needle Orientation

Longitudinal Approach (IN-PLANE)

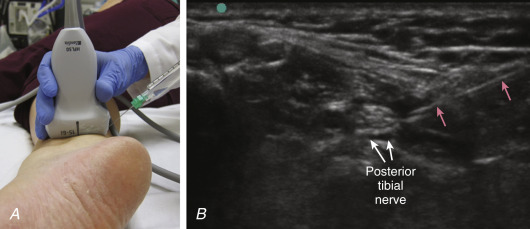

The needle is inserted lateral and parallel to the long axis of the transducer ( Figure 34.5 A ). As the needle passes under the transducer, the entire length of the needle can be visualized ( Figure 34.5 B). The trajectory of the needle must be midline and parallel to the transducer in order to visualize the needle in its entirety. A longitudinal approach, or in-plane technique, for needle-tip visualization is recommended for novice providers performing nerve blocks.

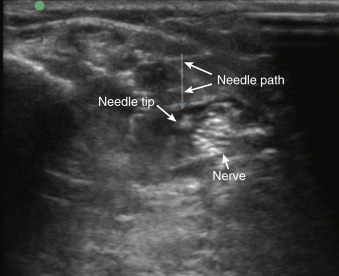

Transverse Approach (OUT-OF-PLANE)

The needle is inserted midline and perpendicular to the long axis of the transducer at a steep angle (greater than 70–80 degrees) to the skin ( Figure 34.6 ). The needle tip is visualized only as a hyperechoic dot as it passes through the ultrasound beam ( Figure 34.7 ). Safe and successful execution of this technique relies on confident visualization of the needle tip, which requires proficient spatial-motor skills to manipulate both the transducer and needle. For this reason, a transverse approach, or out-of-plane technique, may be considered suitable for those with more experience.

Femoral Nerve Block

Indications

An ultrasound-guided femoral nerve block is an excellent tool to decrease pain from proximal lower extremity injuries. In particular, the femoral nerve block is ideal for pain reduction in cases of hip fracture (intertrochanteric and subtrochanteric), femur fractures, and patellar injuries. In patients with a hip fracture, a femoral nerve block gives moderate pain reduction but does not provide complete analgesia to the hip because the obturator nerve, one of the three nerves that innervate the hip, is not blocked by this approach. However, this technique can significantly decrease the need for intravenous opioid medications, reducing the risk of adverse effects, including respiratory depression, confusion, and hypotension, especially in elderly patients.

A well-performed femoral nerve block with anesthetic tracking laterally under the fascia iliaca can also anesthetize the lateral cutaneous nerve, which together innervate the anterior and lateral thigh and can be used for lacerations or abscesses. Even though the risk of developing compartment syndrome of the thigh is very rare, we recommend consulting with the primary surgical service before performing a femoral nerve block.

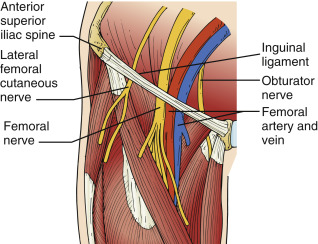

Anatomy

The femoral nerve is one of the branches of the lumbar plexus arising from the first through fourth lumbar ventral rami (L1–L4) before descending toward the lower extremity. At the level of the inguinal canal, the femoral nerve is located just lateral to the femoral artery, beneath the fascia iliaca and superficial to the iliopsoas muscle; together these structures constitute the important landmarks for this nerve block ( Figure 34.8 ).