Peripherally Inserted Central Infusion Catheters

Peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) were introduced in the early 1970s. Initially, they were used for long-term venous access in children,1,2 cancer patients,3 and malnourished patients.4,5 Increasingly, PICCs are being requested for a wide variety of patients requiring intermediate to long-term central venous access.6–14 Several factors account for the dramatic growth of this venous access device, including the emergence of specialized nurses trained in bedside PICC insertion; the dramatic growth in home health care services, allowing patients to receive their intravenous therapy at home; the development of PICC quality assurance programs; and the availability of interventional radiologists to provide backup for PICC placement in difficult patients and to manage complications.15–19 Advantages of PICCs compared with other central venous access devices include their ability to be placed at bedside, ease of removal, low rate of insertion complications, ease of exchange, no risk of pneumothorax, and relatively low cost. Disadvantages of PICCs include that they require adequate peripheral veins; they do not last as long as tunneled catheters or implantable ports; they require daily or regular care; they may restrict patient activity, especially when placed at the elbow; and the small lumen of some catheters limits infusion rates and may make aspiration for blood draws difficult.

Catheter Types

Catheter Types

PICCs are small-bore catheters designed to be placed through a peripheral arm vein into the central veins. Midline catheters are a shorter version of a PICC and typically terminate in the axillary vein. Midline catheters usually are placed at bedside by skilled nurses and do not require a chest radiograph to document tip position.

Most PICCs are made of polyurethane or silicone elastomer (Silastic). These materials provide a relatively soft, durable, and biologically inert catheter. Polyurethane allows a thinner wall construction compared with silicone, resulting in a larger inner lumen and therefore higher flow rates.20–22 In the late 1980s, midline catheters and PICCs made from Aquavene (Menlo Care, Menlo Park, CA), an elastomeric hydrogel material composed of polyurethane and polyethylene oxide, were introduced. Once inside the vein, the material becomes hydrated and the catheter softens and expands by two gauge sizes within 30 minutes of insertion. These catheters reportedly had a decreased rate of phlebitis and infection.23–25 Reports of anaphylactoid-type reactions with these Aquavene-based catheters, however, led to their withdrawal from the market in 1997.26–28

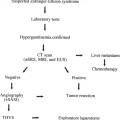

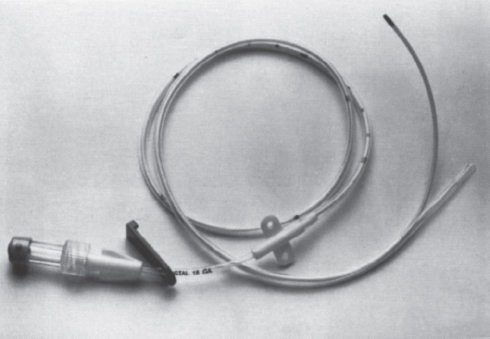

Currently available PICCs range in size from 2 to 6F outer diameter and are available as single-lumen (Fig. 25–1) or double-lumen catheters (Fig. 25–2). The inner lumen diameters range from 16 to 26 gauge. PICCs are also available in two different types of catheter tips: an open-ended catheter tip, consisting of a simple end-hole; and a closed-ended valved catheter tip (Groshong, Bard Access Systems, Inc., Salt Lake City, UT). The Groshong PICC has a slitlike two-way valve at the catheter tip that is closed in the resting state. The valve opens inward with aspiration and outward for infusion. The advantages of the Groshong PICC are that it may decrease catheter clotting, it requires only weekly saline flushes, and in one report its use resulted in a 21% cost savings over a 6-week period.29

FIGURE 25–1. Peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC). A 4F single-lumen device is shown. A wide variety of catheter sizes are available with single or double lumens (see text). (Photo courtesy of Arrow International; used with permission.)

Indications and Contraindications for Placement

Indications and Contraindications for Placement

The PICCs may be used to administer a wide variety of intravenous therapies, including antibiotics, antifungals, chemotherapy, intravenous fluids, blood components, vasopressors, immunosuppressive/antirejection drugs, anticoagulants, total parenteral nutrition (TPN), and analgesics. They also may be used for blood drawing if special care is taken to flush the catheter adequately afterward. Administration of blood components and aspiration for blood draws are best performed through at least an 18-gauge lumen. The use of PICCs for TPN has been debated, especially in regard to concern for a higher infection rate; however, several studies have documented the successful use of PICCs for TPN with favorable infection rates.4,5,30–32

Alternative choices for intermediate to long-term venous access include the Hohn catheter, Hickman catheter, or subcutaneous ports. The choice of whether to place a PICC versus one of the other venous access devices depends on a variety of factors, including referring clinician preference, patient preference, type and duration of access needed, and available sites for venous access. With optimal catheter care, PICCs can last several weeks to months. Some anecdotal reports state that some patients have had functioning PICCs for longer than 2 years, and several studies have reported catheters that have remained functional for longer than 1 year.7,9,33 Such reports represent the exception rather than the rule, however. PICCs often must be removed or changed after a few weeks or months because of catheter clotting, cellulitis, thrombophlebitis, catheter sepsis, inadvertent removal, or catheter degradation.

Midline catheters typically can remain in place between 1 and 4 weeks, with a mean patency of approximately 2 weeks. They have an increased incidence of axillary vein thrombosis. Several series have reported that PICCs can last several weeks to months, with a mean catheter duration of 20 to 36 days reported with interventional radiology placement and 20 to 28 days with nursing placement.9,33–37 Another study noted a mean PICC dwell time of 72.7 days with interventional radiologic placement.18 A further measure of PICC adequacy is the number of catheters required to complete the intended intravascular therapy, which ranges from about 56 to 76% with a single PICC and up to 93% with placement of two PICCs.7–9,18,36,37

FIGURE 25–2. Double-lumen PICC insertion kit. (Photo courtesy of Arrow International; used with permission.)

There are few contraindications to PICC placement. PICCs usually can be safely placed regardless of existing coagulopathy or thrombocytopenia. Unlike tunneled central catheters, active infection or bacteremia does not contraindicate placement, provided intravenous antibiotics are administered through the PICC. Contrast allergy or elevated serum creatinine is a relative contraindication for placement using venographic guidance with iodinated contrast agents. Alternatives to the use of iodinated contrast include carbon dioxide gas venography or ultrasound for guidance.35,38,39 The lack of a suitable peripheral vein precludes placement; however, this is a relatively uncommon occurrence. Central venous thrombosis or occlusion poses a problem for PICC placement. Occasionally, a guidewire can be used to traverse the thrombotic vein, or contrast injection may identify collaterals, thus permitting central venous placement of the catheter tip. Provided hyperosmolar and vesicant fluids are not to be administered, the PICC catheter may be left peripheral to the occluded central vein, resulting in a midclavicular or axillary placement of the catheter tip. A recent study showed that PICCs placed in noncentral veins can provide reliable, safe intravenous access for administration of many medications and isotonic solutions for about 2 weeks’ duration.40

Placement of a PICC is relatively contraindicated in any person on hemodialysis or in whom dialysis is anticipated (serum creatinine level >3.0 mg/dL). This contraindication also includes patients with renal transplants and those undergoing other forms of dialysis, such as continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. As supported by the Dialysis Outcomes Quality Initiative (DOQI), it is unadvisable to place a PICC in these patients to preserve their peripheral veins for future hemodialysis access.41 An alternative in these patients, as well as in patients with unsuitable peripheral veins, is to place the catheter through one of the jugular veins, thereby allowing the PICC to function as a small-bore central catheter. The jugular PICC can be tunneled for convenience.42

Insertion Technique

Insertion Technique

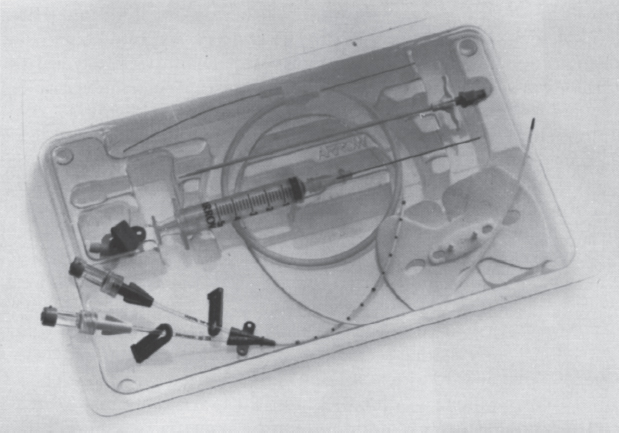

Strict attention to sterile technique is imperative when placing PICCs. All persons in the procedural suite, including the patient, should wear a cap and mask. The physician or nurse performing the procedure should wear a gown and gloves. The patient’s arm should be sterilely prepared and draped. A povidone/iodine or chlorhexidine solution typically is used for skin preparation. Usually PICCs are inserted either at the bedside by a nurse or in the interventional radiology suite. The PICC insertion kit provides virtually all the equipment needed to place the catheter (Fig. 25–3).

Bedside Placement

The bedside technique for placement of PICCs typically uses a breakaway needle or peelaway cannula technique.43 A tourniquet is applied to the upper arm to find a suitable vein. Typically, a vein in the antecubital fossa is punctured by visualization or palpation, with the basilic vein being preferred for cannulation. For superior vena cava placement, measuring from the point of insertion, along the vein tract to the sternal notch, and down three intercostal spaces, can estimate the desired intravascular catheter length. A sterile field is created, and a strict sterile technique is observed. Venipuncture is performed with the breakaway needle, and the PICC is threaded a few inches through the introducer once blood return is obtained. The introducer needle then is withdrawn from the puncture site, and the breakaway needle is removed by pulling the needle apart. The PICC then is threaded further to the measured length, and appropriate placement is verified by chest radiograph. Alternative techniques for bedside placement have been described and include the use of a portable ultrasound device and Seldinger technique.44–46

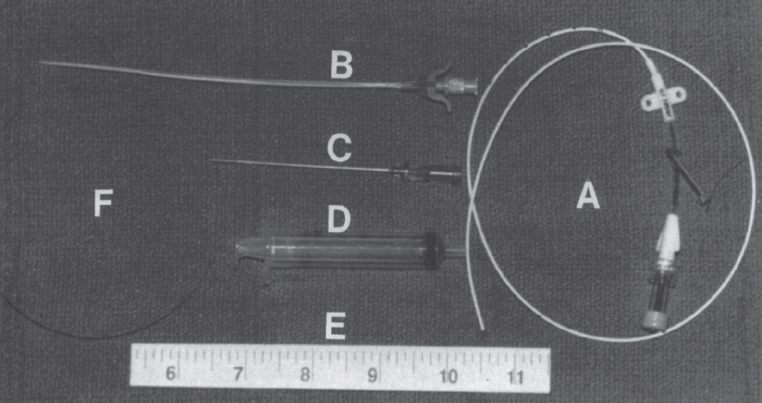

FIGURE 25–3. Typical PICC catheter insertion kit. Contents of the kit include: (A) catheter; (B) peel-away sheath with dilator assembly; (C) 21-gauge needle; (D) 5-mL syringe; (E) ruler; and (F) 0.018-inch guidewire.

Interventional Radiologic Placement

Usually no anesthesia, analgesics, or sedation is required. A tourniquet usually is placed around the upper arm. An appropriate vein is chosen for puncture. Commonly used access sites include the basilic, cephalic, and brachial veins. The basilic vein is the preferred access. The cephalic vein route is more susceptible to catheter malposition and phlebitis.47 The brachial veins (venae comitantes) are often of smaller caliber and are in close proximity to the brachial artery. Therefore, extreme caution should be exercised when cannulating these vessels, especially in coagulopathic patients. A sterile field is created, and strict sterile technique is observed (Fig. 25–4a). Guidance can include palpation, venography, or ultrasound. Interventional radiologic placement often is requested when no visible veins are present or after unsuccessful placement attempt at bedside. Therefore, venographic or sonographic guidance is commonly used.9,18,35,38,48,49 For venographic guidance, a vein more peripheral to the anticipated insertion site is cannulated with a small intravenous catheter and contrast injection performed to identify a suitable vein, usually in the upper arm.49 Carbon dioxide gas can be used as an alternative to iodinated contrast agents.39 For ultrasound-guided access (Fig. 25–4b), usually a 7 to 10 mHz linear transducer is used with the transducer placed inside a sterile sleeve to maintain sterility. The intended PICC insertion site is anesthetized with subcutaneous lidocaine. Using either venographic or ultrasound guidance, a 21-gauge needle is introduced into the vein (Fig. 25–4C). A 0.018-inch guidewire then is advanced into the vein using fluoroscopic guidance (Figs. 25–4d and 4e). A peelaway introducer sheath with a dilator is advanced over the guidewire (Figs. 25–4f). A small cutaneous incision at the insertion site can facilitate placement of the peelaway sheath/dilator assembly. Certain catheters are approved by the manufacturer for trimming. If the PICC is to be trimmed, the guidewire is advanced to the superior vena cava/right atrial junction, and the wire can be bent at the insertion site or marked with a hemostat to measure the appropriate intravascular catheter length. Alternatively, the desired catheter length can be determined by laying the catheter on the patient. The catheter then is trimmed to the appropriate length, the dilator is removed from the peel-away sheath, and the catheter is advanced through the sheath to the cavoatrial junction (Fig. 25–4g). Occasionally, the catheter will not thread even with the stylet provided, and use of a 0.018-inch hydrophilic guidewire is necessary to achieve central venous access. Alternatively, central venous access may not be obtained because of central venous thrombosis or occlusion, which can be confirmed by injection of a small volume of contrast via the PICC or peel-away sheath/dilator assembly. Once the catheter tip is at the desired location, the peel-away sheath is removed by pulling outward on the tabs (Fig. 25–4h), and the catheter is affixed to the skin by using suture or tape (Fig. 25–4i). A chest radiograph then is taken to document appropriate catheter tip placement (Fig. 25–4j).

Placement of a PICC in a pediatric patient can pose certain challenges but is usually successful, with either nursing or interventional radiologic placement.6,8,33,35,48,50

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree