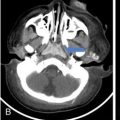

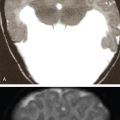

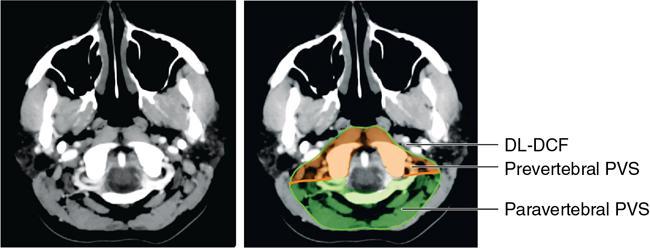

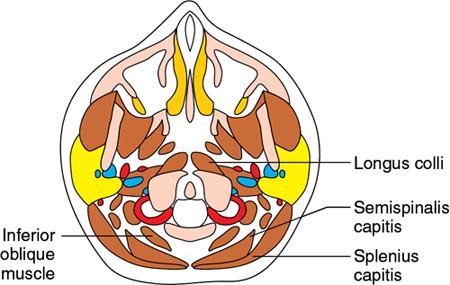

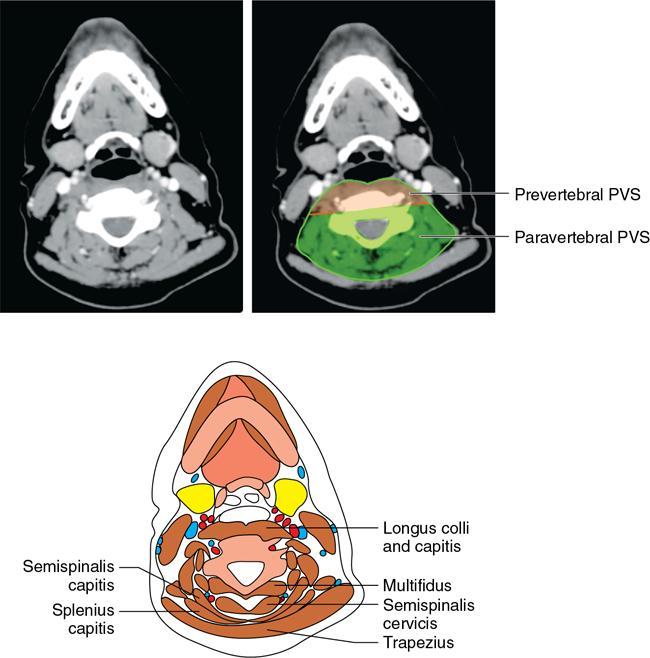

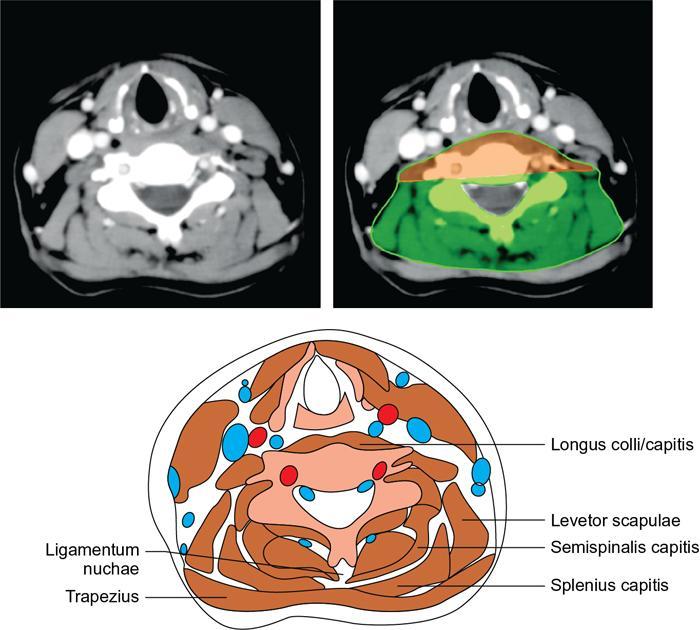

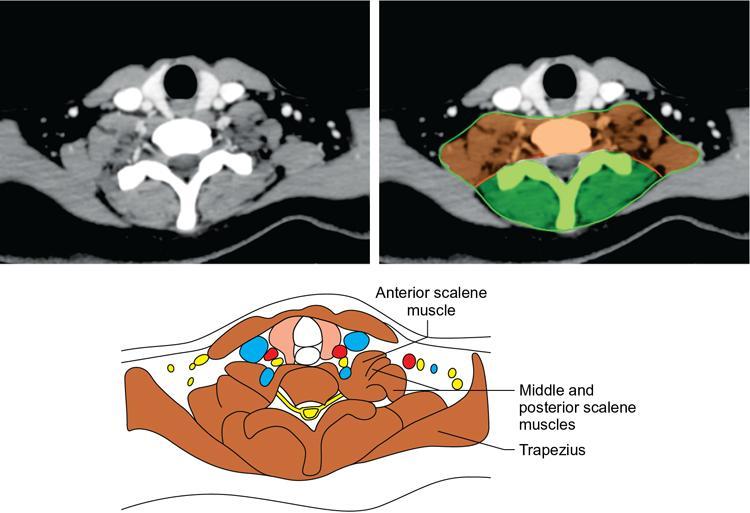

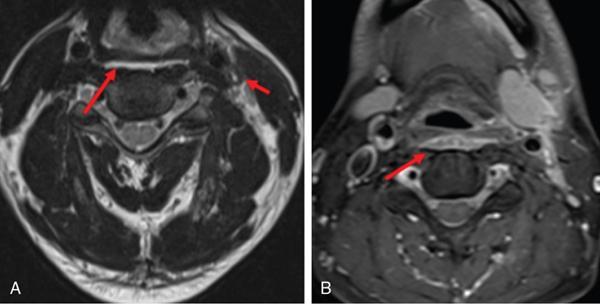

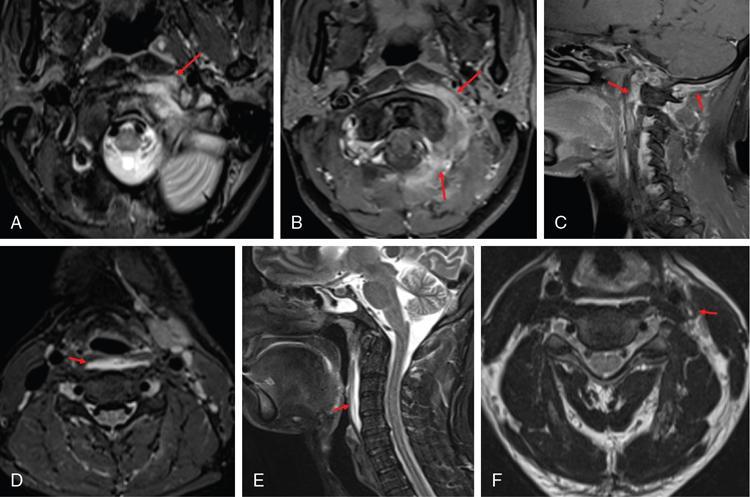

Anita Nagadi The perivertebral space (PVS) is a midline space that surrounds the vertebral column and associated musculature and extends from the skull base to the superior mediastinum. This space is bound by the deep layer of the deep cervical fascia (DL-DCF), which is attached to the transverse processes of the cervical vertebrae, enveloping the paravertebral musculature, and posteriorly attaches to the ligamentum nuchae. The perivertebral space is further subdivided into the prevertebral and paravertebral portions. These spaces are demarcated by the cervical transverse processes, the prevertebral PVS lying anteriorly and the paravertebral PVS lying posteriorly. The prevertebral PVS is related anteriorly to the retropharyngeal space and danger space and laterally to the carotid spaces and the anterior aspects of the posterior cervical space. The perivertebral PVS lies deep to the posterior cervical space. The DL-DCF is a tough barrier that prevents the spread of disease across compartments. The only structures that pierce the DL-DCF are the roots of the brachial plexus, which traverse across into the posterior cervical space and then onto the axilla. The prevertebral PVS contains the longus colli and longus capitis muscles, the anterior, middle and posterior scalene muscles, the brachial plexus roots, the vertebral artery and vein and vertebral bodies. The perivertebral PVS contains the posterior vertebral elements, proximal portions of the brachial plexus and the paravertebral muscles. The paravertebral muscles consist of multiple groups of muscles arranged in symmetric pairs. Knowledge of the anatomy, relationships and contents is paramount to understanding and interpreting pathology in this region. The commonest pathologies occurring in this space are infections and metastases, the epicentre being the vertebral body. Longus colli/capitis complex Anterior and lateral rectus Anterior, middle and posterior scalenus muscles Superficial muscles – splenius capitis, splenius cervicus Suboccipital muscles Transversospinalis muscles – semispinalis capitis, semispinalis cervicus, rotatores cervicis, interspinales, intertransversarii Vertebral arteries and venous plexus Brachial plexus Brachial plexus Vertebral body Posterior vertebral elements This condition is characterized by acute inflammation of the longus colli tendon anterior to the C1–C2 vertebrae, secondary to deposition of hydroxyapatite crystals within the tendon. The typical clinical presentation is that of middle-aged or elderly patients with complaints of neck pain, stiffness, fever or odynophagia. This is a nonsurgical, self-limiting condition that is usually managed with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. CT: Amorphous or coarse calcific specks in the longus colli tendon are pathognomonic, typically lying anterior to the C1–C2 vertebrae. This is usually associated with mild swelling of the prevertebral muscles and a small fluid effusion. The nonexpansile effusion may extend into the retropharyngeal compartment. On IV contrast administration, there is no peripheral enhancement, which helps distinguish the effusion from a retropharyngeal abscess. MRI: The calcific specks may be difficult to appreciate on MRI and appear hypointense on T*W images. Oedema in the prevertebral muscles and small retropharyngeal effusion are better seen on MRI and appear T2 hyperintense. Occasionally, mild vertebral oedema may also be seen. In the correct clinical setting of neck pain, fever and limited mobility, CECT is the first modality of choice. Presence of prevertebral calcification at C1–C2 is pathognomonic of longus colli tendonitis. An associated RPS effusion is seen commonly. If an RPS effusion is present, other causes such as IJV thrombosis, pharyngitis, previous neck irradiation should be excluded by reviewing all relevant structures. The commonest pitfall is mistaking an RPS effusion for an RPS abscess. Absence of rim enhancement and smooth tapering margins help distinguish the former from the latter (Fig. 3.19.1). A perivertebral abscess occurs in the setting of infection in this space, the epicentre of infection most commonly being the vertebral body or the intervertebral disc (spondylodiscitis). Infection may rarely follow prior neck or spinal surgery. Direct seeding of the prevertebral muscles (e.g. trauma) is rare. Infective spondylodiscitis occurs as a result of haematogeneous seeding in either the vertebral body or disc. In the western world, the commonest cause of infective spondylodiscitis is pyogenic (Staphylococcus aureus), elsewhere the commonest organism being Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infection in the perivertebral space originating from the vertebral body/discs spreads to the prevertebral muscles, resulting in inflammation (phlegmon) and eventually abscess formation. Spread is limited by the deep cervical fascia, and infection may be directed to the epidural compartment with resultant cord/neural compression. Pyogenic spondylodiscitis involves the discs and end plates and presents more acutely. TB spondylodiscitis, on the other hand, is more insidious in onset and originates in the vertebral body with relative sparing of the endplates and discs. Subligamentous spread results in involvement of two or more vertebral bodies. The collections/abscess in TB spondylodiscitis tends to be larger and may occasionally calcify in chronic cases. Patients present with fever, pain, restricted movement and or dysphagia/odynophagia. In the setting of epidural extension, features of myelopathy/cord compression may be seen. The predisposing conditions include elderly age, diabetes, IV drug abuse and other conditions leading to immune compromise (e.g. chemotherapy, transplant, etc.). Initial findings may be subtle and limited to mild endplate erosions and prevertebral soft-tissue swelling. In 2–3 weeks, endplate destruction and reduced disc space are evident with reactive sclerosis setting in the latter. In TB spondylodiscitis, patients may present with vertebral collapse and calcifications in the prevertebral soft tissues. Prevertebral space soft-tissue oedema/phlegmon/rim-enhancing abscesses are seen. The retropharyngeal space is anteriorly displaced, and minor oedema may be present. It is important to map the craniocaudal and anteroposterior extent of the prevertebral abscess for surgical or percutaneous drainage. Any epidural extension and evidence of cord compression should be actively sought. On bone windows, vertebral body/endplate erosions are well visualized. Multiplanar reformats are useful in mapping the extent of bony involvement. On MRI, vertebral body oedema is seen as hypointense signal on T1- and hyperintense signal on T2-weighted images. Intradiscal abscess may be visualized as T2 hyperintensity with restricted diffusion on DWI. Prevertebral soft-tissue oedema/abscess is well delineated on T2 and postgadolinium T1 fat-suppressed images. Epidural abscesses are well visualized on postgadolinium fat-suppressed T1-weighted images. Cord signal alteration or cord compression is best assessed on the T2-weighted images. In the appropriate clinical context, CECT is the modality of choice. Determining the site of disease (PVS vs RPS), delineation of soft-tissue involvement, extent of bony destruction and ability to aid surgical planning make this an easy first choice. When epidural extension is suspected, a contrast-enhanced MRI is useful in mapping the disease extent as well as delineating the presence or absence of cord compression (Fig. 3.19.2).

3.19: Perivertebral space

Relevant imaging anatomy

Prevertebral Space PVS

Paravertebral PVS

Muscles

Vessels

Nerves

Bones

Inflammatory pathology

Acute calcific tendonitis of longus colli

Clinical presentation

Imaging

Differential diagnosis

Imaging pearls and pitfalls

Clinicoradiological approach

Infective pathology

Perivertebral abscess

Pathology

Clinical presentation

Imaging

X-ray.

Computed tomography.

Magnetic resonance imaging.

Differential diagnosis

Imaging pearls and pitfalls

Clinicoradiological approach

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree