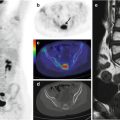

Fig. 4.1

Coronal CT (a), PET (b), and PET/CT fusion (c) images show focal 18F-FDG uptake in the left pelvis, corresponding to the ovarian follicle

In young patients, the thymus is frequently seen on PET as an inverted-V-shaped structure (Fig. 4.2), or as a unilateral structure with right or left extensions (Fig. 4.3), with homogeneous or patchy tracer uptake (Fig. 4.4). In children and in young adults who have undergone chemotherapy, the thymus is an important site of 18F-FDG uptake as this organ uptake may persist for as long as 2 years after the end of therapy. Jerushalmi and coworkers studied a population of 160 patients (age 3–40 years) and found that 28 % exhibited thymic 18F-FDG uptake. Within this subgroup, 80 % were younger than 10 years, 17 % showed uptake only at the baseline study, 6 % during treatment, 8 % at the end of treatment, and 27–40 % during follow-up [3]. It is also important to be aware of normal anatomic variants and variants in FDG uptake patterns. For example, there is a normal variant in which the thymus extends superiorly to the left brachiocephalic vein and anteriorly to the brachiocephalic artery or left common carotid artery (Fig. 4.5). This superior extension of the thymus should not be mistaken for a mediastinal mass or lymphadenopathy [4].

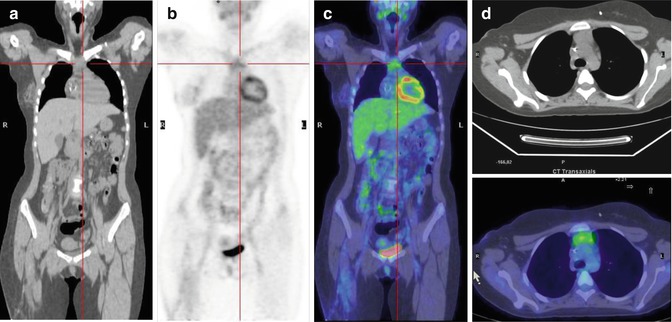

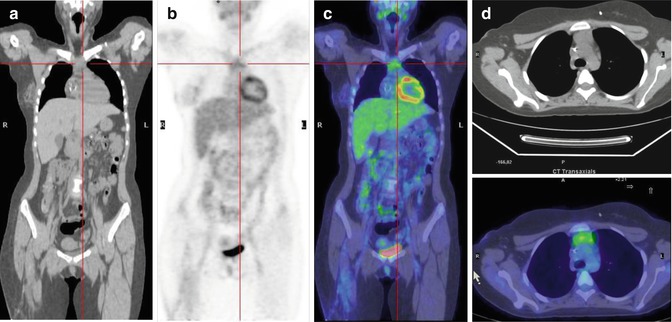

Fig. 4.2

A 14-year-old girl administered chemotherapy for osteoblastic osteosarcoma of the right femur. Coronal CT (a), PET (b), and PET/CT fusion (c) images show soft tissue 18F-FDG uptake by the inverted-V-shaped thymus in the anterior mediastinum. (d) Axial CT and PET/CT fusion images show the thickened thymus in the anterior mediastinum, in front of the aortic arch

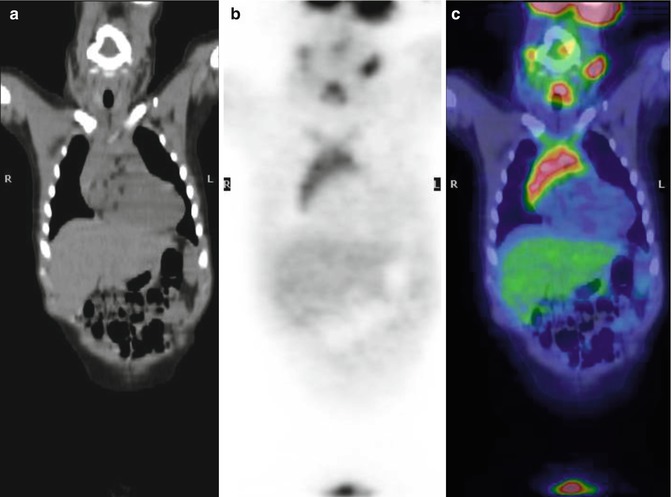

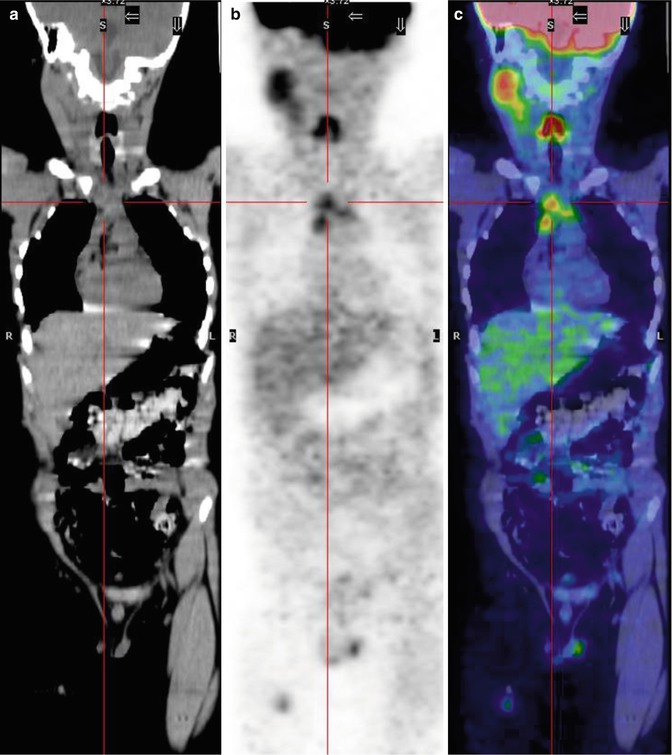

Fig. 4.3

A 5-year-old boy 4 months after the end of chemotherapy for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Coronal CT (a), PET (b), and PET/CT fusion (c) images show intense 18F-FDG uptake by the thymus, which has a unilateral right extension

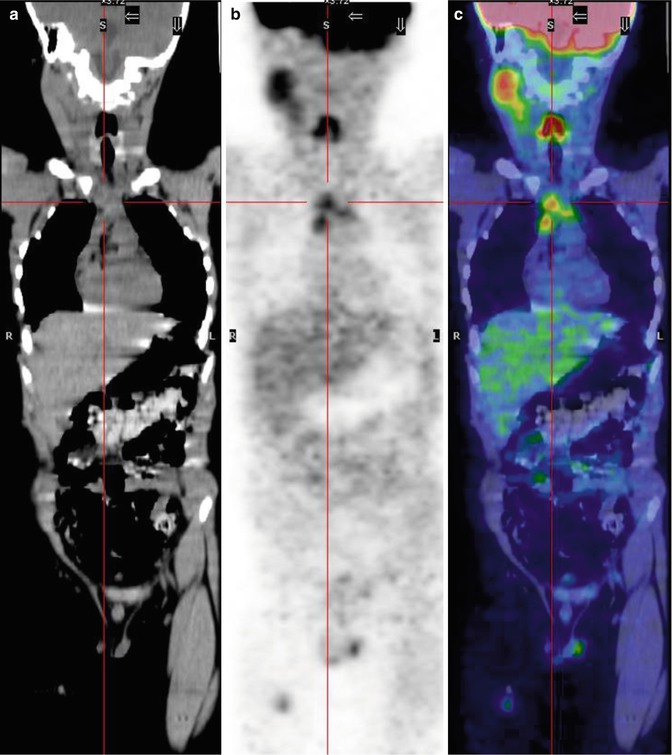

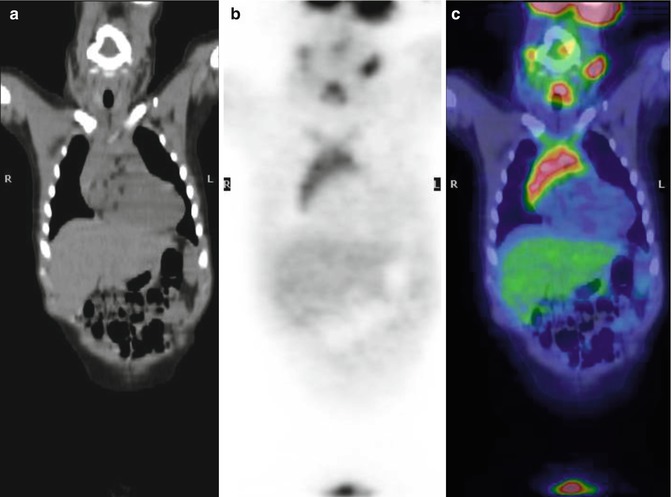

Fig. 4.4

A 6-year-old boy with autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS). Coronal CT (a), PET (b), and PET/CT fusion (c) images show patchy 18F-FDG by the inverted-V-shaped thymus

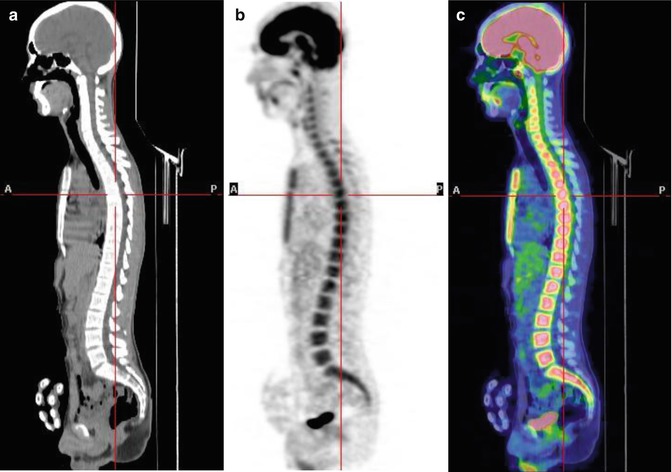

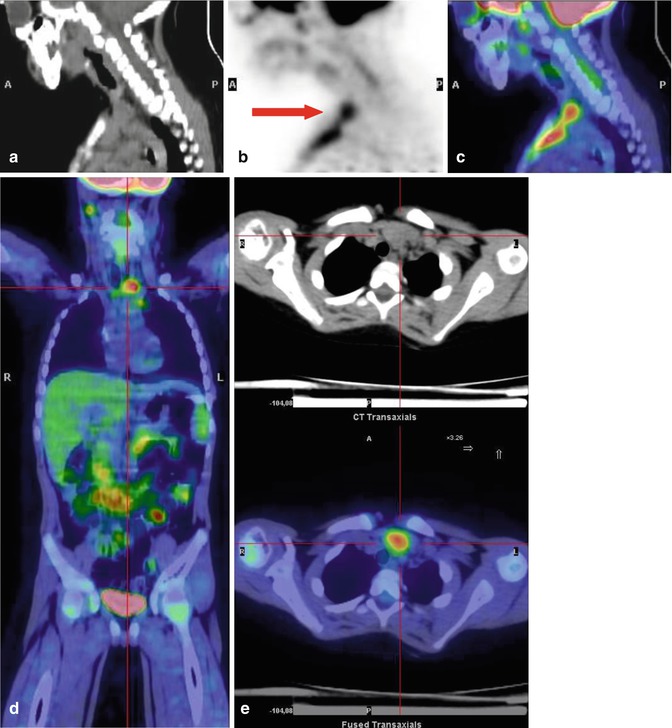

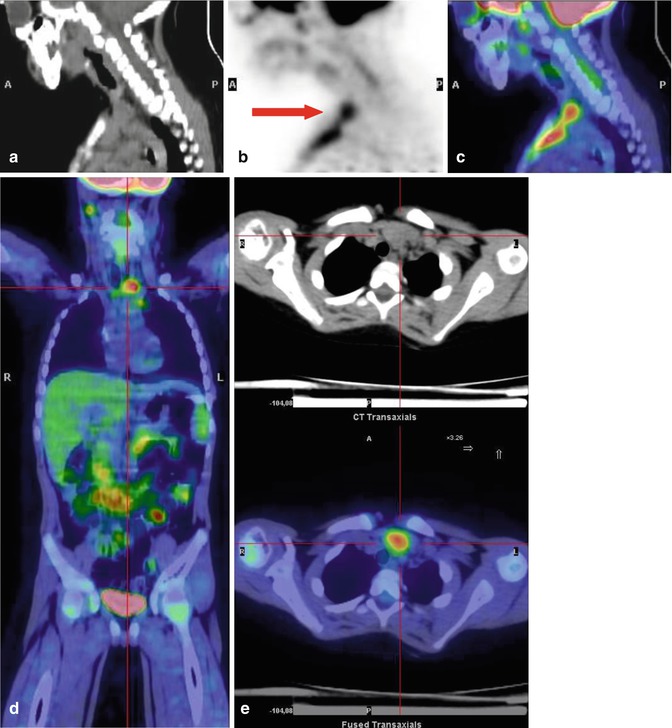

Fig. 4.5

A 4-year-old boy treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Sagittal CT (a), PET (b), and PET/CT fusion (c) images show an extension of the thymus to the superior mediastinum (red arrow in b). Coronal PET/CT fusion image (d) and axial CT and PET/CT fusion images (e) show the extension of the thymus superiorly to the left brachiocephalic vein and anteriorly to the left common carotid artery

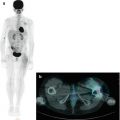

In addition to the thymus, significant uptake is frequently seen in the bone marrow and spleen, probably due to normal growth. After chemotherapy or granulocyte colony-stimulating factor therapy, this activation is significantly increased such that homogeneity is an important criterion for the diagnosis of non-tumoral disease (Fig. 4.6) [5].

In children, it is possible to observe the metaphysis in long bones such as the femur or tibiae, because during growth, the interface between the epiphysis and diaphysis is 18F-FDG avid (Fig. 4.7).

The palatine and nasopharyngeal tonsils and Waldeyer’s ring are lymphoepithelial tissues located near the oropharynx and nasopharynx (Figs. 4.8 and 4.9). These immunocompetent tissues are the immune system’s first line of defense against ingested or inhaled foreign pathogens. In children, the PET study frequently shows enhanced and symmetric uptake, which helps to distinguish neoplasms from inflammatory pathologies.