Authors

Year

No. of cases

Approach

Patient population

Pathology

Percent of patients with GTR (%)

Mortality (%)

Major morbidity (%)

Permanent minor morbidity (%)

Hoffman et al. [8]

1983

61

TCIH/ITSC

Pediatric

All

NA

20a

NA

NA

Neuwelt et al. [9]

1985

13

OTT

Adult/pediatric

All

60

0

0

20

Lapras et al. [10]

1987

86

TCIH/OTT

Adult/pediatric

All

65

5.8†

5.8†

28

Edwards et al. [11]

1988

36

TT/OTT/ITSC

Pediatric

All

NA

0

3.3

3.3

Pluchino et al. [12]

1989

40

ITSC

Adult/pediatric

All

25

5

NA

NA

Luo SQ et al. [13]

1989

64

OTT

Adult/pediatric

All

21

10

NA

Vaquero et al. [14]

1992

29

TCIH/ITSC/OTT

Adult/pediatric

All

NA

11

NA

NA

Herrmann et al. [87]

1992

49

IHTC/ITSC

Adult/pediatric

All

NA

8

NA

NA

Bruce and Stein [6]

1995

160

ITSC/TC/OTT

Adult/pediatric

All

45

4

3

19

Chandy et al. [88]

1998

48

ITSC/OTT

Adult/pediatric

“Benign lesions”

55

0

NA

NA

Kang et al. [89]

1998

16

OTT/ITSC/TCIH

Adult/pediatric

All

37.5

0

0

19

Shin et al. [90]

1998

21

OTT

Pediatric/adult

All

54.5

0

0

5

Konovalov et al. [3]

2003

201

OTT (54 %)

Adult/pediatric

All

58

10‡

NA

>20

ITSC (34 %)

Bruce [91]

2004

81

ITSC/TCIH/OTT

Adult/pediatric

All

47

1

2

NA

Hernesniemi et al. [4]

2008

119

ITSC (93 %)/OTT (7 %)

Adult/pediatric

All

88

0

1

4.9

Open surgery is the treatment of choice for benign tumors. Depending on specific histology, open surgery has a variable role in the treatment of malignant tumors and tumors with mixed elements, either as a means of cytoreduction prior to chemotherapy and/or radiation [15, 19, 20] or as the best option to eradicate benign elements in mixed tumors after chemotherapy/radiation [7, 21]. Additionally, through immediate removal of obstructing lesions, open surgery can obviate the need for permanent cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) diversion. Open surgery also offers comprehensive tissue sampling for a group of tumors that can be of mixed histology and are notoriously difficult to diagnose.

The management strategy for achieving control of tumor growth is strongly dependent on histology. While benign tumors are often cured by surgery, germinomas, on the other extreme, are exquisitely radiosensitive and best managed with radiation therapy [22]. Most malignant pineal region tumors benefit from a combination of surgical resection followed by chemotherapy and/or radiation. In rare instances of mixed tumors containing both benign and malignant elements, surgical resection may be necessary to remove benign elements after prior chemotherapy/radiation has eradicated the malignant portion. Open surgery also facilitates comprehensive tissue sampling reducing the risk of sampling error given the rarity, diversity, and similar radiographic appearance of different of pineal tumor histologies (Fig. 35.1).

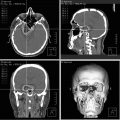

Fig. 35.1

Similar imaging characteristics of pineal lesions with different histologies. T1-weighted MRIs, precontrast (left panels) and postcontrast (right panels), of three patients with pineal region tumors: (a) ependymoma, (b) pineocytoma and (c) germinoma

Stereotactic radiosurgery has an unproven role as an adjunct or even an alternative to open surgery. The great variety of tumors that occur in the pineal region and the need to direct adjuvant therapy based on histopathologic diagnosis mandate that, with few exceptions, treatment, including stereotactic radiosurgery, should not be pursued without a tissue diagnosis. Stereotactic biopsy followed by stereotactic radiosurgery may prove to be a reasonable alternative to open surgery in selected cases, but this strategy is currently most appropriate for patients with significant medical contraindications to open surgery. Stereotactic radiosurgery may also have an additional role as an alternative to whole-brain radiation in the treatment of select radiosensitive tumors or in the adjuvant setting following surgical resection. Retrospective series of patients with pineal region tumors treated with stereotactic radiosurgery report variable outcomes [23, 24]. The interpretation of treatment efficacy in these studies is complicated as the patient populations include different or unknown histology, and nonuniformity of additional treatments including craniotomy and radiation therapy. Predictors of poor outcome following stereotactic radiosurgery include radiographic signs of tumor necrosis, prior radiation treatment and high grade histology [23].

Surgical Management: An Overview

Initial management of a pineal region mass includes evaluation for hydrocephalus, which is present in most patients. Although ventriculoperitoneal shunting is acceptable, endoscopic third ventriculostomy is preferred, achieving the same end without exposing a patient to the potential problems of shunt malfunction, shunt infection, and abdominal seeding of a malignancy. After CSF diversion, a procedure to obtain tissue is indicated, either via a stereotactic, an endoscopic, or an open approach. Either diverting procedure provides a convenient opportunity to assay CSF for malignant germ cell tumor markers (α[alpha]-feto-protein or β[beta]-HCG) and cytology, which can in very rare cases obviate the need for tissue sampling. If these markers are elevated in either CSF or serum, then by definition a malignant nongerminomatous germ cell tumor (NGGCT) is present, and chemotherapy and radiation therapy can proceed without the need for histologic confirmation.

Stereotactic Biopsy

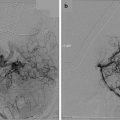

Although safe, stereotactic biopsy in the pineal region requires more care and planning than biopsies of most other areas of the brain. An anterolateral approach is favored with a pre-coronal entry point just behind the nexus of the superior temporal line and the hairline (Fig. 35.2). Using image guidance, the trajectory can be adjusted to enter a gyrus at the pial surface, avoid the lateral ventricle, and steer clear of any obvious vasculature that may be distorted into the path of the biopsy needle by the tumor itself [25].

Fig. 35.2

Eighteen year-old male presented with headache, nausea and vomiting. MRI revealed a pineal lesion (a), with dissemination into the third ventricle (a, red arrow). Following endoscopic third ventriculostomy, a stereotaxic needle biopsy was obtained. Stereotaxic needle trajectory with a pre-coronal and slightly lateral entry point was chosen to avoid the ventricular system, and eloquent cortical territory (b)

Close proximity of the target to the deep venous system and a lack of adjacent tissue turgor should theoretically increase the likelihood of a significant biopsy-induced hemorrhage. In fact, such hemorrhages appear to be mildly more common in the pineal region, but they are rarely of any clinical significance [26, 27]. Some series have suggested a higher morbidity associated with pineal region biopsies compared with routine biopsies, whereas others do not. In any case, overall complication rates are low and are almost always a function of transient exacerbations of existing symptoms [25, 28–31]. A rare, but nonetheless reported complication of stereotaxic biopsy is metastatic seeding of a pineoblastoma along the biopsy tract [32]. The major drawback to biopsies is the limited tissue sampling that makes definitive diagnosis difficult when dealing with these widely diverse and often heterogeneous lesions.

Endoscopic Biopsy

Some authors have advocated obtaining tissue specimens endoscopically during the same operation as the third ventriculostomy. Although a potentially elegant one-step solution to CSF diversion and tissue diagnosis, such a strategy necessarily biases tissue sampling towards one quadrant of the tumor capsule. Also, unless a flexible endoscope is used, endoscopic biopsy and third ventriculostomy must be performed through two separate burr holes and as such offers no less “invasiveness” than stereotactic biopsy and third ventriculostomy. Recent studies have demonstrated the feasibility of both biopsy and third ventriculostomy through a single burr hole positioned midway between the two trajectories [33].

Craniotomy for Open Resection

Although diagnostic biopsies are a suitable first option in some cases, an open approach is generally preferred. The advantages of an open resection are numerous, including generous tissue sampling, potential obviation of a shunt, and the ability to proceed with a radical resection if indicated after intraoperative pathology consultation [34]. The relative advantages of pursuing radical resection depend on an accurate histopathologic diagnosis and must be weighed against rates of morbidity and mortality from radical surgery. Complications from open surgery can be serious and even catastrophic typically resulting from postoperative hematoma, venous infarction from vein sacrifice, thalamic injury from dissection of the anterior tumor capsule, and visual deficits if the occipital transtentorial approach is used. However, when complete tumor removal can be achieved, the risk of postoperative hemorrhage into a subtotally resected tumor is reduced. Minor complications include infection and exacerbation of existing ataxia or Parinaud phenomena. Pineal region surgery is certainly not trivial, but within the past 25 years, major morbidity and mortality from published surgical series have improved dramatically and over the past quarter century has dropped to 0–2 % [35] (Table 35.1).

A craniotomy is performed when cytoreductive radical resection is the goal, and as mentioned above, this surgery provides significantly more reliable material for histological diagnosis. There are a series of approaches to access the pineal region, and the selection of a particular one depends on factors such as the surgeon’s experience, and anatomical factors. In general, the approaches can be divided into supratentorial and infratentorial [35–37].

Supratentorial approaches provide a wider lateral exposure, and are preferred when the tumor mass extends significantly into the supratentorial compartment, or has grown laterally away from the natural reach achieved with a midline trajectory from the infratentorial supracerebellar (ITSC) approach. The supratentorial approaches include the occipital transtentorial (OTT) (Fig. 35.3), the transcallosal interhemispheric (TCIH), and the rarely used transcortical-transventricular (TT) approach which is limited to the setting of ventricular dilatation and tumor extension into the lateral ventricle [10, 34, 35, 38, 39]. Some of the surgical morbidity can be related to deficits specific to a given approach. One of the major inconveniences of the supratentorial approaches is that important deep venous structures such as the vein of Galen and the internal cerebral veins lay between the surgeon and the lesion. The presence of these veins in the field increases the risk of venous infarct, and might obstruct the operative field limiting.

Fig. 35.3

Fifty two year-old female presented with nausea and vomiting over the course of few weeks. MRI revealed a pineal region lesion with no involvement of the third ventricle but with inferior extension dorsal to the brainstem, and obstructive hydrocephalus (a). Following endoscopic third ventriculostomy, the patient underwent a craniotomy through occipital transtentorial approach (trajectory shown with red arrow in a), and postoperative imaging showed gross total resection (b)

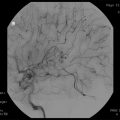

Infratentorial access to the pineal region is obtained though the ITSC corridor (Fig. 35.4). With the patient preferably in the sitting position, the superior surface of the cerebellum is dissected from the tentorium and the precentral cerebellar vein is divided, allowing the cerebellum to fall by gravity clearing an unobstructed pathway to the pineal region [35, 40]. With the sitting position, gravity minimizes retraction, and prevents blood from pooling in the microsurgical field. Additionally, the deep venous structures lie superior to the tumor mass, facilitating resection of the lesion. This approach is favorable for removing tumor extending into the third ventricle and velum interpositum. Disadvantages of the approach include limited access to lateral and supratentorial areas. Also, the sitting position carries a risk of air embolism, pneumocephalus and subdural hematoma, although proper precautions can minimize the risk [35, 41].

Fig. 35.4

Twenty five year-old female presented with Parinaud’s syndrome and headache. MRI revealed a pineal region lesion with extension into the posterior portion of the third ventricle (a). A craniotomy with an infratentorial supracerebellar approach was performed for tumor resection (trajectory shown with red arrow in a), and postoperative imaging showed gross total resection (b)

Treatment Results by Tumor Histology

The field of oncology is predicated on the belief that any treatment modality must be evaluated on the basis of efficacy in treating groups of patients bound by a common diagnosis. This diagnosis is almost always made on the basis of tissue histology. Pineal region tumors can arise from any of the myriad cell types that normally occur in and around the pineal gland, as well as from the range of ectopic tissues that can be trapped near the pineal gland during embryogenesis. Because few places in the body can match such cellular diversity and biopsies of pineal lesions have been demonstrated to be safe, histologic diagnosis of pineal region tumors is mandatory unless tumor markers are positive. MRI is excellent at defining the relationship between tumor and adjacent anatomic structures but is not able to distinguish between tumors of different histologies (Fig. 35.1).

Tumors in the pineal region can be categorized as benign or malignant. Alternatively, they can be classified into one of four broad histologic categories: (1) pineal cell; (2) germ cell; (3) glial cell; and (4) miscellaneous. Although surgical results significantly influence the outcome for these patients, individual prognosis is heavily dependent upon tumor type. The rarity of individual histopathologic types within the pineal region makes it difficult to generate sufficient numbers of patients treated to evaluate individual therapies, however some generalizations can be made.

Benign Pineal Region Tumors

Benign tumors account one third of the masses found in pineal region [6]. These are composed mainly of well-differentiated ependymomas, meningiomas, teratomas, pineocytomas, and rare pilocytic astrocytomas. In each case, radical resection is the standard of care if it can be performed within a reasonable degree of safety. Gross total resection provides the best chance for a cure or extended remission but this goal must be weighed against the risks associated with radical resection. Surgical series demonstrate good outcomes over a range of pathologies, although there is a need in the literature for surgical outcomes to be analyzed according to specific histology. Only a few small surgical series are dedicated to benign pineal lesions of a single histological type [42–44].

Glial Tumors

Glial neoplasms encountered in the pineal region can present in three different categories: (a) brainstem astrocytomas, usually tectal lesions that extend rostrally, (b) “true” pineal astrocytomas that arise from the supporting astrocytes of the pineal gland itself, and (c) ependymomas associated with the third ventricle. Brainstem astrocytomas that grow into the pineal region are solid and, although they may be “low grade,” are generally invasive. These are not amenable to aggressive resection and require irradiation after biopsy [36, 45]. The “true” pineal astrocytomas are often cystic, encapsulated, and resemble pilocytic astrocytomas on histology [46]. These can be completely resected and have excellent long-term results. Anaplastic gliomas and glioblastomas have also been encountered in the pineal region [3, 4]. Surgical outcomes from ependymomas are binary, depending on the degree of anaplasia. Pineal region ependymomas with low cellularity and few mitoses have excellent long-term outcomes although they may recur more readily than ependymomas associated with the lateral ventricles [47].

Pineal Parenchymal Tumors

Arising from the melatonin-producing cells of the pineal gland, pineal parenchymal tumors exist along a histopathologic continuum from benign and indolent pineocytomas to malignant and aggressive pineoblastomas. Tumors of intermediate grade are referred to as mixed pineal parenchymal tumors, and various classification schemes that are tied to prognosis have been proposed [42, 48–52]. Making an accurate pathologic diagnosis is difficult even with generous tissue sampling. The rarity of these tumors makes the aggregation of sufficient numbers of patients for an instructive clinical trial difficult. Further complicating matters is the variable behavior of tumors with similar histopathologies depending upon age of presentation.

Amidst the paucity of data to direct clinical decisions, certain general treatment guidelines are apparent. The goal for well-differentiated pineocytomas should be a cure, at least in adults. There is some evidence that this standard is unrealistic in pediatric cases where pineocytomas may behave more aggressively [53].

The reported low recurrence rates with gross total resection of pineocytomas (overall survival approximately 100 % at 40 months median follow-up) has established a new standard of care for these low grade tumors [3, 4, 42]. Outcomes following radiosurgical treatment of pineocytoma have been favorable as well [54–56], although the few reported adult cases had only had a short follow-up [56] and included at least one adult treatment failure resulting in death from CNS metastasis [55]. One pediatric pineocytoma radiosurgical series reported four of seven treatment failures resulting in death during a follow-up of 3 months to 4 years [57], although recently, more favorable results have been reported [23].

At the other end of the neoplastic spectrum are pineoblastomas. Although pineoblastomas often appear identical to pineocytomas on MRI, they are histologically indistinguishable from primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNETs) and behave in a similar clinical fashion. Like PNETs, they tend to be more aggressive in children than in adults [58], and within the pediatric population they are increasingly aggressive with decreasing age of presentation [59–66]. Although some indication of increased survival exists in both adults [19] and children [20] undergoing open surgery, no statistically rigorous study has examined the impact of extent of resection on survival or disease progression. In the absence of such studies, it seems logical to follow the standard of care for medulloblastoma (pinealoblastoma, shares phonotypical characteristics of PNET) for which significant survival benefits are apparent after reduction of tumor mass under 1.5 cm3 [67]. The few published cases of stereotactic radiosurgery for pineoblastoma report poor results with the most recent showing local tumor control of 30 % at 2 years from diagnosis [24, 54–57], likely reflecting their malignant nature and potential to spread through CSF. The relative utility of radiosurgery cannot be ascertained based on a few published cases except to say that radiosurgery does not appear to be a “magic bullet” for these lesions, and it does not address the metastatic potential of these tumors. Ultimately, prognosis for pineoblastoma is most predicted by age of presentation and disease dissemination at the time of diagnosis. Although far from comprehensive, evidence suggests that resection has a beneficial impact on survival.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree