This chapter addresses the pulmonary involvement observed in gastrointestinal diseases, particularly gastroesophageal reflux (GER), Heiner syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), the hepatopulmonary syndrome (HPS), and pancreatitis. Although the purported mechanisms currently invoked to explain their concurrent associations vary, several general modes of involvement include (1) the direct effect of spillage of food or gastric contents into the airway, resulting in aspiration pneumonia; (2) a secondary, immune-mediated process, inflaming specific elements of the lung; and (3) injury to the lung from medications used to treat specific gastrointestinal disorders, such as sulfa derivatives or immunosuppressive agents integral to the management of IBD. The true etiology of the observed involvement is still unclear, and much work is being done to unravel the molecular mechanisms at play. This is a fruitful field for translational research and wide open for the development of novel pharmacologic agents with precise targets.

The pulmonary involvement concurrent with gastrointestinal diseases is often clinically subtle and requires a high index of suspicion. The radiologic manifestations might lag behind the establishment of respiratory compromise, and only specialized testing such as high-resolution computed tomography (CT), permeability studies with labeled proteins, or comprehensive pulmonary function tests (PFTs) may be sensitive enough to detect the evolving pathophysiology. Increased use of these techniques, in addition to bronchoalveolar lavage and validation of various biomarkers, would allow better definition of the prevalence of these disorders and their natural history. As in many fields of pediatrics, the data on pulmonary manifestations of gastrointestinal diseases are limited by sample size and general research investment. Much of the data is extrapolated from adult studies or animal models.

For the most part, management is supportive and conservative. Increasing recognition of specific entities such as immune-mediated alveolitis or granulomatous involvement of the airway would result in the implementation of therapies that can be lifesaving or significantly improve the patient’s prognosis.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

GER, defined as the passage of gastric contents into the esophagus, is a common physiologic event of little consequence in most infants. It occurs throughout the day, and is most frequent in the immediate postprandial period. In the first 3 months of life, more than 50% of full-term infants regurgitate more than once a day, and 15% regurgitate more than four times a day. These numbers increase from 4 to 6 months of age, when greater than 80% regurgitate. By the time the child is 18 months old, the prevalence of reflux decreases to 5%.

In contrast to GER, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) refers to the significant clinical manifestations of excessive reflux, which manifest in a wide spectrum of settings, including failure to thrive, irritability, feeding difficulties (especially feeding aversion), bleeding, and anemia. Extraesophageal manifestations include chronic hoarseness, upper airway obstruction owing to vocal cord edema, recurrent bronchitis or pneumonia, and exacerbation of reactive airway disease.

The pulmonary manifestations of GERD are controversial. Pathophysiologically, it is often impossible to ascribe a causal relationship to these two phenomena, presenting a which-came-first conundrum: Are the pulmonary complications observed in children with reflux a direct result of the exposure of the airway to acid or gastric contents, or are the cough, bronchospasm, and deranged diaphragmatic mechanics the primary causes of the suspected reflux? Acid spillage into the distal esophagus may trigger increased vagal tone resulting in bronchospasm and worsening reflux as the infant mobilizes abdominal muscles to aid in exhalation against the bronchospasur constricted airways.

The clinical manifestations of airway disease in which reflux is suspected as an etiologic factor include recurrent pneumonia, chronic bronchitis/bronchiolitis, chronic cough, asthma, and apparent life-threatening events (ALTEs). Neonatal conditions that are associated with a heightened risk of GER include prematurity, postrepair esophageal atresia with or without associated tracheoesophageal fistula, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, and chronic lung disease of infancy.

Pathophysiology

It is now believed that the primary mechanism responsible for reflux in children is an inappropriate relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter. In contrast to in adults, the resting pressure of the sphincter is rarely abnormally low in children. Other factors contributing to reflux in this patient population include reduced esophageal capacitance and increased intra-abdominal pressure. Important developmental factors also play a role, including decreased fundic compliance, discoordination of gastric emptying, and the shorter length of the intra-abdominal esophagus. Esophageal peristalsis and mucosal protective factors are less efficient in infants, especially when born prematurely, and this helps explain the increased occurrence of pathologic reflux in this vulnerable population.

Experimental work in animals and some studies in humans suggest that pulmonary involvement in the presence of acid reflux can be the result of at least two very different, but potentially complementary or synergistic mechanisms. Exposure of the lower esophagus of kittens to hydrochloric acid has been associated with a mild increase in measured bronchial smooth muscle tone. Similar results have not been consistently documented in adults or in children, although evidence suggests that there is a loss of protective lower esophageal sphincter tone in the presence of established esophagitis. A second mechanism considered pertinent to the pathophysiology of reactive airways in the presence of reflux is the stimulation, through vagal mediators, of receptors in the upper airway by microaspiration of acid or other irritants.

Loss of the protective reflexes, which normally prevent aspiration from above, would aggravate pulmonary manifestations in any patient with concomitant risk factors. The most vulnerable children presenting with pulmonary signs and symptoms suggestive of GERD are children with associated neuromuscular handicaps that place them at risk for aspiration.

Developmental Aspects

The mechanisms that coordinate breathing and swallowing are not fully developed until 34 weeks gestation. Premature infants are often treated for apnea suspected to be caused by reflux; however, acidic and nonacidic events occur frequently in this population, and they are not always causally related to the respiratory irregularities or apnea that occurs regularly in this setting of central nervous system immaturity. The technique of intraluminal electrical impedance, which is limited to institutions with a research interest, allows identification not only of the direction and volume of the bolus (antegrade or retrograde), but also the effectiveness of the esophageal clearance mechanisms. When paired with a pH sensor, this technique can shed light on important factors not otherwise detected with the more commonly used gold standard,—prolonged pH intraesophageal monitoring.

As infants mature, the larynx descends and moves more effectively to provide a tight seal during sucking and to close the trachea with a well-developed epiglottis; the risk of aspiration decreases significantly. For many former premature infants, however, the vulnerabilities can persist for years and become a major challenge in their day-to-day management; this is especially the case with infants who have sustained intracranial bleeds or injuries, infants with hydrocephalus, infants with anoxic encephalopathy, and infants who have required prolonged respiratory support and artificial orogastric or gavage feedings. In children who are fed by gastrostomy tube, GER is common even when studies before gastrostomy tube placement are negative for GER.

In children with spastic cerebral palsy and other syndromes that may include mental retardation, constipation is common. A particularly dangerous form of aspiration occurs when stool softeners and laxatives containing mineral oil are administered orally for management of chronic constipation. Medium-chain triglycerides (MCT) oil used to increase the caloric density of formulas also may cause a lipoid pneumonia when aspirated. Lipoid pneumonia can manifest insidiously from continued microaspiration, but also can have a sudden onset when a large aspiration of lipid occurs. Oropharyngeal discoordination, loss of protective cough reflexes, and airway penetration all contribute to the development of lipoid pneumonia. The pulmonary injury can manifest insidiously over months or years with tachypnea and unexplained fever, but little cough or congestion. The findings on radiologic studies can be impressive ( Fig. 5-1 ).

Congenital Anomalies

Infants born with congenital anomalies affecting the oropharynx and other midline structures (e.g., cleft palate, laryngotracheal cleft) and infants with disproportionately large tongues or small mandibles (macroglossia, as seen in various syndromes or in the Pierre Robin sequence) are at a major disadvantage with respect to their capacity to prevent aspiration from above and in the presence of reflux ( Fig. 5-2 ). The presence of abnormal communication between the esophagus and the airway (tracheoesophageal fistulas) results in spillage of saliva and particulate food into the airway. Even after repair of the fistula, most children with these anomalies have a dysmotility of their foregut, with more severe GER, and increased likelihood of associated tracheomalacia or laryngomalacia.

Serious respiratory and gastrointestinal complications, such as recurrent pneumonia, obstructive airway disease, airway hyperreactivity, GERD, and esophageal stenosis, are frequent in patients with a history of esophageal atresia/tracheoesophageal fistula, although the frequency of such events seems to decrease significantly with age. Because chronic aspiration can lead to recurrent pneumonia and impaired pulmonary function, it is essential in patients with a history of esophageal atresia/tracheoesophageal fistula that these recognized respiratory complications be excluded before respiratory symptoms are simply attributed to “asthma.” Common etiologies of respiratory symptoms in patients with a history of esophageal atresia/tracheoesophageal fistula include retained secretions owing to impaired mucociliary clearance secondary to tracheomalacia, and aspiration related to impaired esophageal peristalsis or esophageal stricture or both, recurrence of the tracheoesophageal fistula, or GERD.

Children with neuromuscular disorders, including children with certain forms of spastic cerebral palsy, spinal muscular atrophy, or bulbar involvement, can have recurrent aspiration because of their inability to coordinate the five muscle groups that form the intrinsic muscles of the larynx. These groups are innervated by the trigeminal, facial, hypoglossal, and vagus nerves, along with the important branches, the superior and recurrent laryngeal nerves. Sensory abnormalities and autonomic dysfunction (such as encountered in children with familial and nonfamilial dysautonomic syndromes) can result in prominent and life-threatening lung disease ( Fig. 5-3 ; see Fig. 5-2 ).

Another at-risk group for chronic reflux and pulmonary disease are children with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. The presence of the herniated viscus during the development of the lung often becomes the most life-threatening component of the defect because it profoundly affects lung development and results in pulmonary hypertension. The pulmonary compromise poses the most serious prognostic implications for the child. The effects on esophageal motility can be serious; often there is an associated delayed gastric emptying and severe feeding intolerance. Infants born with congenital diaphragmatic hernia often also have various degrees of pulmonary hypertension, which is usually proportional to the extent of lung hypoplasia. GER is a major problem after surgical repair of the diaphragm because with the stomach in the chest during fetal development, these infants fail to develop a cardiac sphincter, and their esophagus tends to be short and intrinsically dysmotile, as is the rest of the foregut. After surgery (even if an antireflux procedure is performed at the initial surgery), recurrence of GER is common when there is a paraesophageal hernia or slippage of the antireflux wrap. This is a common event when the diaphragm is repaired with a Gore-Tex patch owing to stretch of the patch with growth of the infant allowing slippage of the stomach through the wrap.

There is also an increased risk of reflux in esophageal atresia because even after esophageal anastomosis, these infants are at very high risk for esophageal stricture at the site of the anastomosis and poor distal esophageal motility. Similar to infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia, these infants rarely have a competent gastroesophageal sphincter.

Penetration of gastric contents, acid, or nasal or oral secretions into the airway has deleterious effects on the surface epithelium, triggering the production of mucus, the recruitment of inflammatory cells, and the activation of inflammatory pathways. Surfactant damage, alveolar obliteration, atelectasis, and progressive parenchymal damage result. As a result, interstitial fibrosis can develop with secondary changes in the pulmonary circulation.

Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of vomiting in a child is multifactorial ( Table 5-1 ), and a diagnosis of “reflux” should not be considered seriously until other important reasons for vomiting are ruled out by a thorough history and physical examination. When necessary, ancillary tests help define potentially serious etiologies of vomiting.

| Structural/Anatomic |

| Pyloric stenosis |

| Malrotation |

| Intestinal stenosis/atresia |

| Intussusception |

| Hirschsprung disease |

| Infections |

| Pyelonephritis/cystitis |

| Pneumonia |

| Central nervous system infections |

| Gastroenteritis |

| Otitis |

| Sepsis |

| Metabolic Disorders |

| Organic acidurias |

| Galactosemia |

| Hereditary fructose intolerance |

| Urea cycle defects |

| Fatty acid oxidation defects |

| Central Nervous System Disorders |

| Hydrocephalus |

| Ventricular or intracerebral hemorrhage |

| Chronic subdural hematoma |

| Tumors |

| Gastrointestinal Etiologies |

| Acute appendicitis |

| Gastritis |

| Pancreatitis |

| Allergic enteropathies |

| GERD |

| Cholelithiasis/cholecystitis |

| Hepatitis (infectious, autoimmune, metabolic, drugs) |

| Miscellaneous |

| Medication side effects |

| Lead toxicity |

| Dysautonomic crisis |

Vomiting in an infant is often the presenting symptom for an underlying structural problem or obstruction. In pyloric stenosis, the vomiting is typically projectile and nonbilious. The presence of bilious vomiting is always an emergency because it can result from malrotation or intussusception. Delay in diagnosis of volvulus can have catastrophic consequences, with ischemic damage to the midgut. Vomiting also is a common clinical manifestation of an underlying infection in infants and children, including central nervous system infection, urinary tract infection, otitis media, and pneumonia. Inborn errors of metabolism often manifest with vomiting and failure to thrive. In specific disorders, intolerance to certain carbohydrates (galactose, fructose) or to proteins (urea cycle disorders) can confuse the clinical picture and result in inappropriate management for presumed reflux. Because the child is vomiting, tests designed to identify reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus would invariably be positive, reinforcing the false assumption of reflux as the underlying primary pathology.

Diagnostic Approach

Given the numerous tests available to identify reflux ( Table 5-2 ), it behooves the practitioner to choose the most appropriate test to answer a specific clinical question. A guiding principle in the choice of test to identify reflux is to consider how the results would help guide or change management. Radiologic visualization of the esophagus and stomach is neither particularly sensitive nor specific to identify reflux, but radiography is an excellent and widely available screening test for detecting anatomic defects, such as the critical conditions of obstruction or malrotation.

| TEST | ADVANTAGES | LIMITATIONS |

|---|---|---|

| Barium swallow/upper GI series | Commonly available; inexpensive; best suited to identify anatomic abnormalities | Poor specificity; procedure performed supine; easy to elicit reflux in frightened, crying infant |

| Modified barium swallow | Allows accurate definition of phases of swallow and abnormal structural positions of involved structures; physiologic posture; helps in the management of infants and children with dysphagia and other feeding difficulties | Requires collaboration between experienced speech/feeding and radiology services; not widely available |

| Prolonged pH probe monitoring | Accurate capture of acid reflux events; allows correlation with symptoms; reflects esophageal acid clearance; presents physiologic events over time (18–24 hr), and their timing during the day and night; helps in titration of antacid therapy | Does not identify nonacidic reflux events; difficult to perform in children receiving nasogastric or continuous feedings; not useful in the identification of GER-related ALTEs (see text) |

| Milk scan | Affords a more physiologic setting to determine gastric emptying compared with inert barium | Insensitive to detect aspiration, unless it occurs while isotope is still in the stomach; requires child to be completely immobile for >1 hr under the gamma camera |

| Salivagram | High concentration of isotope allows better demonstration of aspiration from above; helps in visualizing retropharyngeal pooling and esophageal clearance | Not commonly performed; no standards available |

| Intraluminal impedance | Best test available to show bidirectional fluid movement in the esophagus; acid and nonacid events can be identified | Available only in a very limited number of centers at present; analysis is time-consuming and dependent on experience of reader |

| Polysomnography | Provides a wealth of physiologic data reflective of most systems potentially involved in ALTE episodes—EEG, air flow, end-tidal CO 2 , EMG, abdominal and chest wall motion, saturation, ECG video recording, and pH probe; allows temporal correlation between variables | Only performed in a few pediatric centers in the U.S.; requires overnight hospitalization (home monitoring sometimes available through commercial services) |

The modified barium swallow, performed under videofluoroscopic control with the guidance of a feeding or speech therapist who works closely with the radiologist, can provide extremely useful information regarding the mechanics of suck and swallow and the safety of oral feedings ( Fig. 5-4 ). This study is performed with the infant in a more physiologic position (sitting up, as opposed to lying down, as is the case for a routine upper gastrointestinal series) while various textures and barium consistencies are offered via a nipple or cup. In addition to delineating the appropriateness of lip and tongue coordination, bolus propulsion, and traverse through the retropharynx and into the upper esophagus, the test allows an appreciation of the esophageal sweeping peristaltic waves and the effective relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter during swallows.

Monitoring of the changes in acidity occurring in the esophagus is still considered one of the most valuable diagnostic tests to quantify acid reflux and to determine its correlation to symptoms such as irritability, neck posturing and arching, feeding refusal, or nocturnal cough. The pH probe monitoring test can now be performed with slender probes that have proximal and distal sensors; this allows determination of the level reached by the acid refluxate in the esophagus. It also is useful in determining the adequacy of acid-suppressive therapy, a recurrent and very relevant clinical issue that arises when symptoms persist despite what is believed to be an appropriate dose of H 2 -blocker or proton pump inhibitor.

A gastric scintiscan using a Tc 99m–labeled meal also can be performed. This study allows detection of reflux and quantifies gastric emptying over 2 hours. In some cases, markedly delayed gastric emptying appears to contribute to the reflux.

Reflux as Etiology of Pulmonary Pathology

Determining the possible contribution of reflux to pulmonary disease remains a formidable challenge. As already noted, no single test can help make the distinction between aspiration or reflux of food and saliva from above, or of acid and gastric contents from below. Correlation with respiratory events, including apnea, bronchospasm, and cough, requires the simultaneous recording of multiple variables, usually best performed in a sleep laboratory or similarly specialized testing facility. Polysomnography allows measurement of airflow and chest movements and cardiovascular parameters and oxygen saturation, while also capturing REM sleep and, if indicated, swallowing movements. Correlating events that are separated by milliseconds and trying to determine cause-and-effect relationships can be a daunting task and can help explain the dearth of “definitive” studies pertaining to this topic.

Theoretically, labeling of saliva with nuclear isotopes should provide a sensitive way to detect aspiration of secretions from above. The “salivagram” has never been validated as a useful tool for this indication, however. It sometimes provides information on esophageal clearance and even gastric emptying, similar to a formal gastric emptying test performed with labeled formula or solids. Identifying aspiration of gastric contents during a gastric emptying test depends on the aspiration event occurring while there is still sufficient isotope left in the stomach. It does not easily or reliably duplicate the clinical setting of nocturnal aspiration.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Asthma

The etiologic role of GERD in some patients with the more refractory forms of asthma has not been firmly established, although there is evidence (albeit controversial) to suggest that aggressive management of GERD can change the natural history of unremitting steroid dependency and severe bronchial inflammation in some patients. For most patients with uncomplicated asthma, however, it is unclear to what degree stimulation of esophageal vagal mediators plays a role in triggering or aggravating bronchospasm, or even whether reflux exerts its deleterious effects in this population through (micro) aspiration and airway penetration.

Clinical Management

Typical acid reflux symptoms are often absent in patients with asthma referred to a pediatric gastroenterologist for evaluation. Severe bronchospasm and cough can result in chest pain, epigastric discomfort, and nausea indistinguishable from GERD. Increased secretions promote triggering of the gag reflex and nausea, adding to the diagnostic difficulties. In practical terms, the possibility of GERD-aggravated asthma is considered when response to appropriate therapy is inadequate, and when asthma symptoms seem to worsen at night or recur without obvious explanation. Steroid dependence and difficulties in maintaining airway quiescence while receiving anti-inflammatory and bronchodilator therapy should be a “red flag” pointing to GERD as a possible contributor to the refractory nature of asthma. A positive pH probe is more likely in patients with severe asthma than in patients without severe asthma.

In 2001, the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition published clinical practice guidelines for evaluation and treatment of GER in infants and children. In this evidence-based review, a meta-analysis of 13 case series involving 668 patients documented the presence of abnormal pH monitoring studies in more than 60% of infants and children with asthma. Nevertheless, only half of the patients with chronic asthma and abnormal pH studies ever reported gastrointestinal symptoms (including vomiting, regurgitation, and heartburn) suggestive of underlying reflux disease. No clinical features of asthma predicted which children had abnormal pH scores.

There is no pediatric experience that helps predict which children with asthma but without GER symptoms might benefit from empiric antireflux therapy, or how to approach patients with severe asthma who have negative prolonged esophageal pH probe studies. Regarding surgery, a review of six case series involving 258 patients with steroid-dependent asthma showed that 85% of patients who underwent an antireflux operation (fundoplication) were reported to have a decrease in the frequency and intensity of their asthma attacks and were able to reduce their bronchodilator and anti-inflammatory medication dose. The American Thoracic Society and the National Institutes of Health Expert Panel on the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma have issued recommendations to investigate reflux as a possible cause of poorly controlled asthma (in adults), including documenting reflux with pH probe studies, if indicated.

There is some evidence that GER is a possible trigger or aggravating factor in a subgroup of patients with severe asthma. In patients who have frequent exacerbations, nocturnal attacks or cough, frequent need for steroids, or steroid dependence, a trial of aggressive acid suppression (preferably with a proton pump inhibitor) and lifestyle modifications for at least 3 months can be beneficial and should be recommended. For patients without any GER symptoms, but with a positive pH study or a clinical profile that includes recurrent pneumonia, nighttime wheezing, and steroid dependence, the same recommendations apply.

Apparent Life-Threatening Events

In the spectrum of pulmonary complications related to reflux disease, ALTEs hold a special place, given the high anxiety generated by the episodes and the costly evaluation to which many of these infants are subjected when they are admitted to the hospital for investigation of the episode. ALTEs are defined as frightening events affecting infants who, during the episode, appear to require resuscitation (usually mouth-to-mouth breathing for perceived apnea) and look cyanotic (or pale) and lifeless, and who were sometimes observed to have had a preceding gasping, choking, or gagging trigger. In the typical case, an otherwise healthy infant has an ALTE episode when placed supine on a changing table soon after a feed or a bottle. It is not unusual to elicit a history of finding formula in the infant’s mouth, or noticing the infant cough just as the airway clears and the long episode (15 to 40 seconds) subsides. Characteristically, by the time emergency personnel arrive at the home and bring the infant to the emergency department, there is little to support the parents’ concerns about a life-threatening event.

In addition to certain infections (e.g., respiratory syncytial virus in premature infants), the differential diagnosis of ALTEs includes cardiac arrhythmias, central nervous system disorders (including seizures), and metabolic derangements. It is important to consider defects of fatty acid oxidation and other, less common entities because they can be difficult to diagnose unless there is a high index of suspicion and specific tests are obtained shortly after the event.

GER plays a role in a large proportion of children with ALTEs (80% can have abnormal pH monitoring studies, although they seldom are found to correlate with ALTE episodes). Frequent regurgitation is elicited in the history of 60% to 70% of infants presenting with ALTEs.

The understanding of the sequence of events leading to apnea in this setting is that the activation of protective reflexes in the upper airway leads to airway obstruction when refluxate reaches the upper larynx or is about to penetrate the airway. Vagally mediated reflexes can explain the vasomotor and cardiorespiratory changes after the obstructive episode. The likelihood of GER being responsible for the ALTE episode increases if the event occurred within the first hour postprandially, and if the infant was awake (or semiawake) and supine. Changes in position are known to promote relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter, and the presence of a full stomach in the recumbent position favors regurgitation.

Clinical Management

Management of ALTEs associated with reflux focuses on measures geared to decrease the likelihood of reflux; avoidance of the supine position within 1 hour of feedings and thickened feedings have been recommended. If there is a history of symptomatic reflux, acid suppression and improvement in the degree of esophagitis would optimize sphincter function. Diagnostically, a pH monitoring study rarely is helpful because the ALTEs are so random that capturing a whole GER-obstruction-apnea sequence is seldom successful or worth the effort. Conservative treatment is recommended for most infants with ALTEs. This recommendation represents a significant change in the indication for surgery (fundoplication), which used to be the standard of care in some centers for management of GERD-related ALTEs.

All parents, and especially parents whose infants have had an ALTE, should be instructed on back to sleep, the recommendation to encourage sleeping in the supine position. This recommendation has been associated with a major reduction in the incidence of sudden infant death syndrome. Severe GERD has been considered a special circumstance, however, in which a semiprone position can be allowed, provided that the infant is carefully observed and monitored, and the infant’s face rests against a firm mattress. In addition, bottle propping or bottle in bed is recognized as a risk factor for ALTE and aspiration and chronic bronchitis from aspiration as the infant falls asleep with the bottle in the mouth.

Heiner Syndrome

Heiner syndrome is a very rare form of pulmonary hemosiderosis, believed to be due to cow’s milk allergy because in the initial report all infants had precipitins to cow’s milk proteins in their serum. The symptoms in these children were not the symptoms normally expected in idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis (recurrent hemoptysis or intermittent blood-streaked sputum, varying degrees of anemia, and radiographic findings of symmetric diffuse alveolar infiltrates predominant in perihilar regions and lower zones), and all had nonspecific complaints of chronic lung disease and upper respiratory tract disease. These patients apparently improved on a milk-free diet.

In more recent decades, enthusiasm for cow’s milk allergy as the cause of idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis has waned. In a very large series of patients with idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis, no such association was present. Some patients with pulmonary hemosiderosis did not have milk precipitins, whereas many children with milk precipitins did not have pulmonary hemosiderosis. Because of the reported association between cow’s milk allergy and pulmonary hemosiderosis, many children with idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis are placed on milk-free diets, but unless there is unequivocal evidence of true milk allergy, this approach is unjustified. The possible role played by exposure to foreign food proteins should be actively elicited during the history. The onset of symptoms depends on the time of introduction of milk and solid foods and varies in different geographic areas and cultural backgrounds. As mentioned, cow’s milk seems to be the major offender, but individual experiences suggest soy, eggs, and pork also can play a role.

The reported clinical improvement that results from withdrawal of the offending protein seems to be marked. It also is followed by radiologic improvement, which can lag behind symptomatic relief. Demonstration of the causal relationship with cow’s milk protein exposure is not always feasible because parents might be reluctant to allow re-exposure after they have witnessed the dramatic resolution of chronic symptoms and the resumption of normal weight gain and growth.

Heiner syndrome may be considered in any atopic infant or young child who presents with recurrent or chronic respiratory symptoms. A history of chronic cough, pneumonia, bronchitis, and bronchiolitis is often elicited, and a history of frequent visits to the emergency department for wheezing and a suspected diagnosis of asthma. Hemoptysis can occur when the inflammation and alveolar damage progress to intrapulmonary bleeding. Some children can have transient hives and other urticarial rashes, periorbital edema, and allergic shiners. As a result of the chronic nature of the pulmonary involvement, many children are debilitated and have poor weight gain and failure to thrive. Gastrointestinal manifestations are nonspecific and include vomiting and abdominal pain. Diarrhea is more common than constipation, although in some cases, both may be present.

Diagnostic Approach

The chest x-ray findings are nonspecific and reflect the underlying interstitial changes and air trapping caused by small and large airway obstruction. Diffuse and variable infiltrates, patchy pneumonia, interstitial lung disease, and fibrosis can be documented at various times during the course and progression of the condition. Chronic intrapulmonary bleeding results in a microcytic, hypochromic anemia and iron deficiency that can be severe and debilitating.

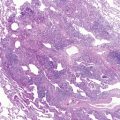

The precipitins against cow’s milk protein fractions can be identified by the micro-Ouchterlony technique; their appearance and concentration can vary depending on the state of sensitization and the temporal proximity of the exposure to the offending protein. These circulating IgG antibodies are not pathognomonic, however, because, as mentioned previously, they have been reported in children who do not manifest pulmonary hemosiderosis. Identification of iron-laden alveolar macrophages in bronchoalveolar lavage is good evidence that bleeding has occurred recently, and that the disease process is still active. The finding of hemosiderin in macrophages from gastric aspirates also is suggestive of the diagnosis, but is less direct than bronchoalveolar lavage. Nevertheless, their presence— notwithstanding the suspected specific protein exposure trigger—should raise the possibility of other entities responsible for pulmonary hemorrhage/hemoptysis in children ( Fig. 5-5 ).