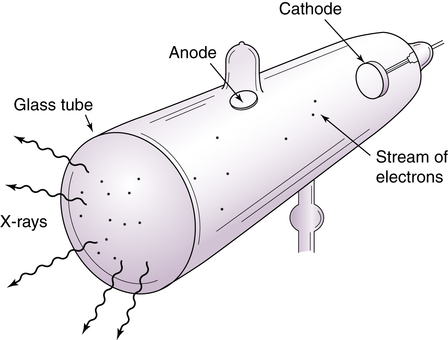

X-rays were discovered on November 8, 1895, by Dr. Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen (Figure 1-1), a German physicist and mathematician. Roentgen studied at the Polytechnic Institute in Zurich. He was appointed to the faculty of the University of Würzburg and was the director of the Physical Institute at the time of his discovery. As a teacher and researcher, his academic interest was the conduction of high-voltage electricity through low-vacuum tubes. A low-vacuum tube is simply a glass tube that has had some of the air evacuated from it. The specific type of tube that Roentgen was working with was called a Crookes tube (Figure 1-2).

On ending his workday on November 8, Roentgen prepared his research apparatus for the next experimental session to be conducted when he would return to his workplace. He darkened his laboratory to observe the electrical glow (cathode rays) that occurred when the tube was energized. This glow from the tube would indicate that the tube was receiving electricity and was ready for the next experiment. On this day, Roentgen covered his tube with black cardboard and again electrified the tube. By chance, he noticed a faint glow coming from some material located several feet from his electrified tube. The source was a piece of paper coated with barium platinocyanide. Not believing the cathode rays could reach that far from the tube, Roentgen repeated the experiment. Each time Roentgen energized his tube, he observed this glow coming from the barium platinocyanide–coated paper. He understood that energy emanating from his tube was causing this paper to produce light, or fluoresce. Fluorescence refers to the instantaneous production of light resulting from the interaction of some type of energy (in this case x-rays) and some element or compound (in this case barium platinocyanide).

Roentgen was understandably excited about this apparent discovery, but he was also cautious not to make any early assumptions about what he had observed. Before sharing information about his discovery with colleagues, Roentgen spent time meticulously investigating the properties of this new type of energy. Of course, this new type of energy was not new at all. It had always existed and was likely produced by Roentgen and his contemporaries who were also involved in experiments with electricity and low-vacuum tubes. Knowing that others were doing similar research, Roentgen worked in earnest to determine just what this energy was.

Roentgen spent the next several weeks working feverishly in his laboratory to investigate as many properties of this energy as he could. He noticed that when he placed his hand between his energized tube and the barium platinocyanide–coated paper, he could see the bones of his hand glow on the paper, with this fluoroscopic image moving as he moved his hand. Curious about this, he produced a static image of his wife Anna Bertha’s hand using a 15-minute exposure. This became the world`s first radiograph (Figure 1-3). Roentgen gathered other materials and interposed them between his energized tube and the fluorescent paper. Some materials, such as wood, allowed this energy to pass through it and caused the paper to fluoresce. Some, such as platinum, did not.

In December 1895, Roentgen decided that his investigations of this energy were complete enough to inform his physicist colleagues of what he now believed to be a discovery of a new form of energy. He called this energy x-rays, with the x representing the mathematical symbol of the unknown. On December 28, 1895, Roentgen submitted a scholarly paper on his research activities to his local professional society, the Würzburg Physico-Medical Society. Written in his native German, his article was titled “On a new kind of rays,” and it caused a buzz of excitement in the medical and scientific communities. Within a short time, an English translation of this article appeared in the journal Nature, dated January 23, 1896.

Roentgen viewed his discovery as an important one, but he also viewed it as one of primarily academic interest. His interest was in the x-ray itself as a form of energy, not in the possible practical uses of it. Others quickly began assembling their own x-ray–producing devices and exposed inanimate objects as well as tissue, both animal and human, both living and dead, to determine the range of use of these x-rays. Their efforts were driven largely by skepticism, not belief that x-rays could do what had been claimed. Skepticism eventually gave way to productive curiosity as investigations concentrated on ways of imaging the living human body for medical benefit.

As investigations into legitimate medical applications of the use of x-rays continued, the nonmedical and nonscientific communities began taking a different view of Roentgen’s discovery. X-ray–proof underwear was offered as protection from these rays, which were known to penetrate solid materials. A New Jersey legislator attempted to enact legislation that would ban the use of x-ray–producing devices in opera glasses. Both of these efforts were presumably aimed at protecting one from revealing one’s private anatomy to the unscrupulous users of x-rays. The public furor reached such a height that a London newspaper, the Pall Mall Gazette, offered the following editorial in 1896: “We are sick of Roentgen rays. Perhaps the best thing would be for all civilized nations to combine to burn all the Roentgen rays, to execute all the discoverers, and to corner all the equipment in the world and to whelm it in the middle of the ocean. Let the fish contemplate each other’s bones if they like, but not us.”

In a similar vein, but in a more creative fashion, another London newspaper, Photography, in 1896 offered the following: