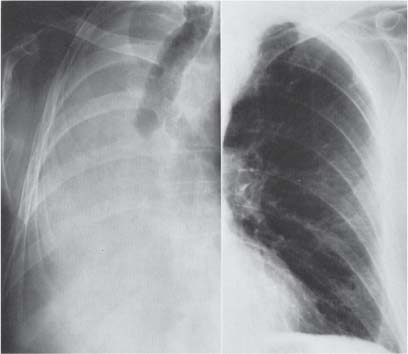

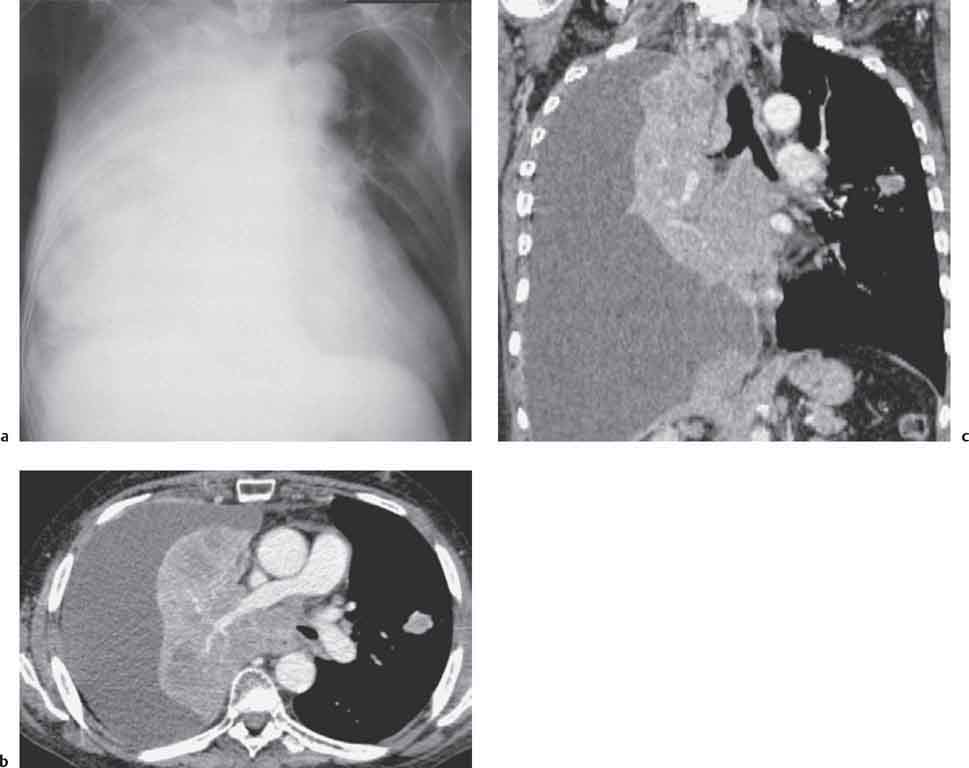

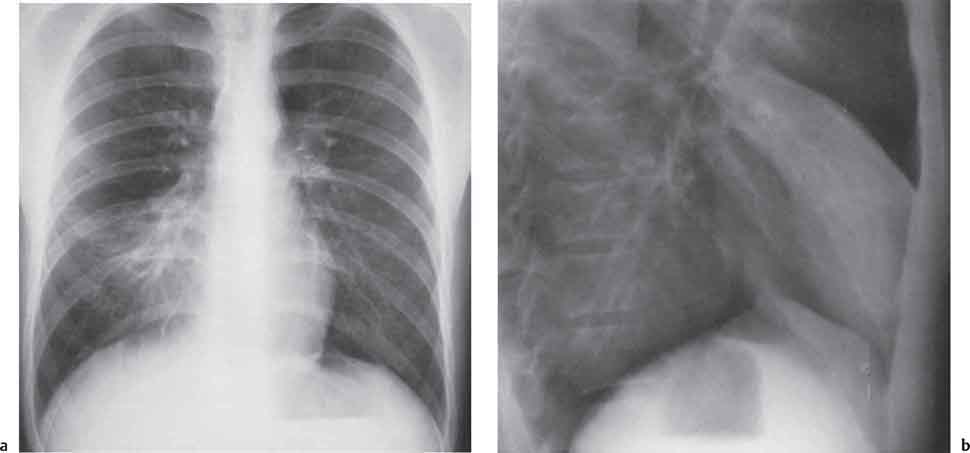

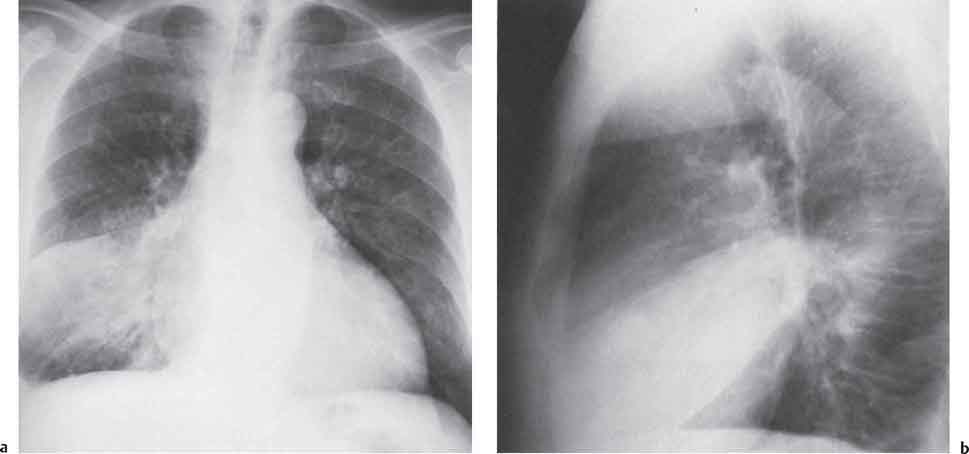

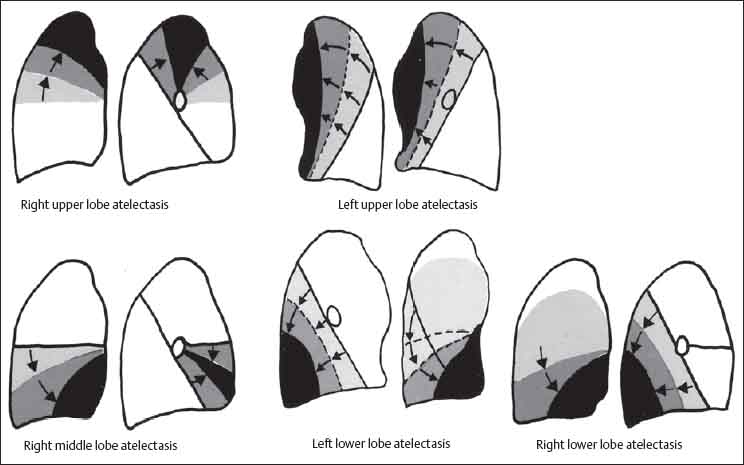

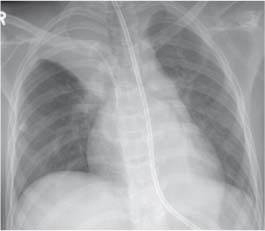

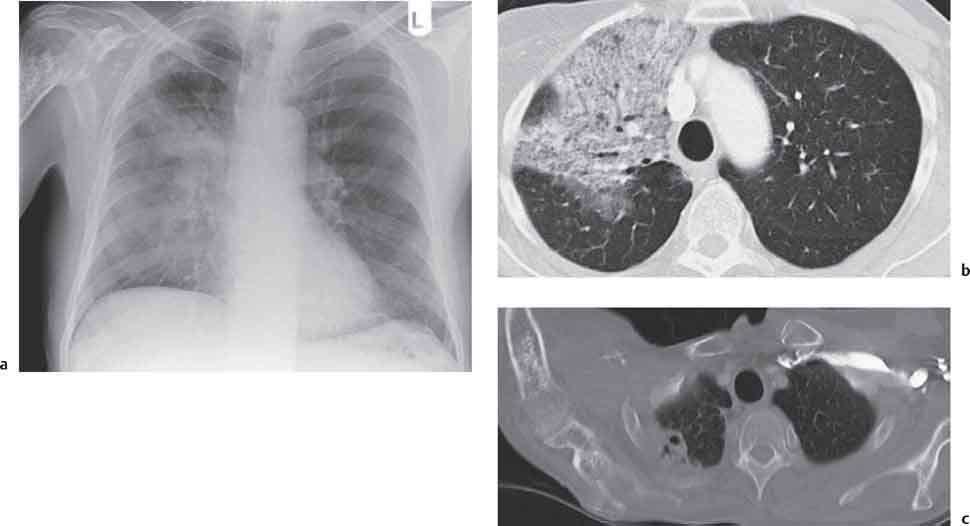

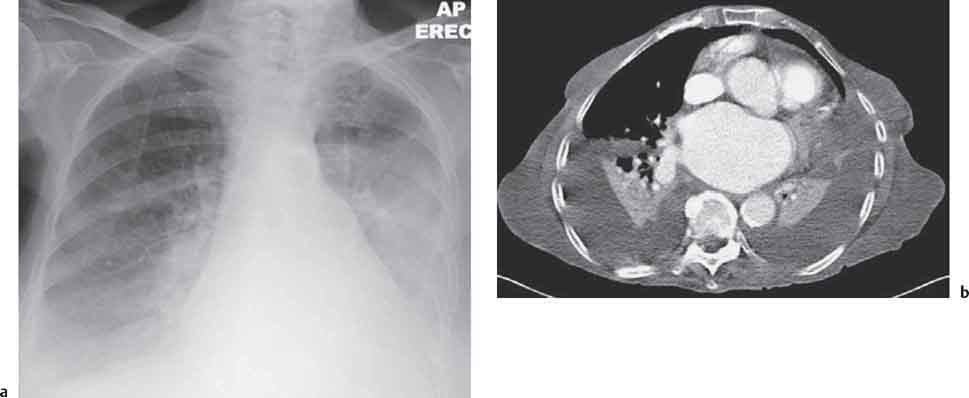

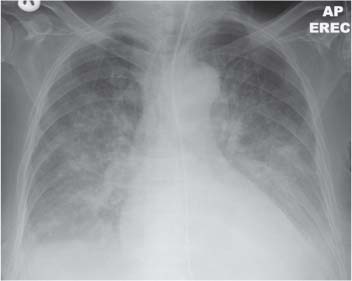

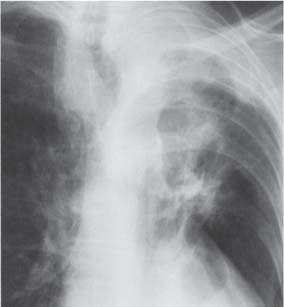

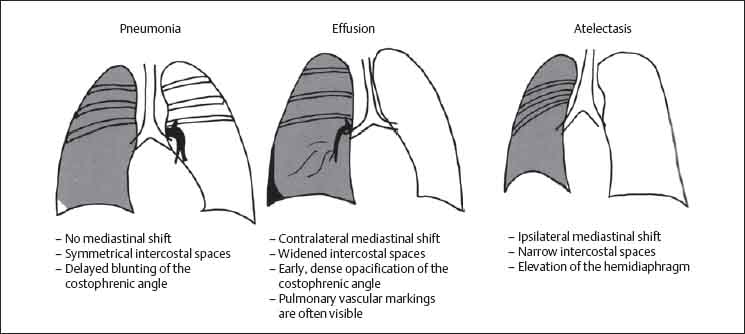

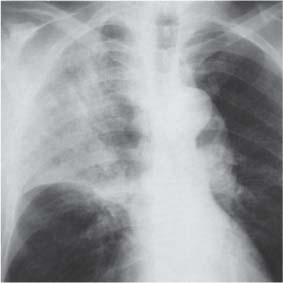

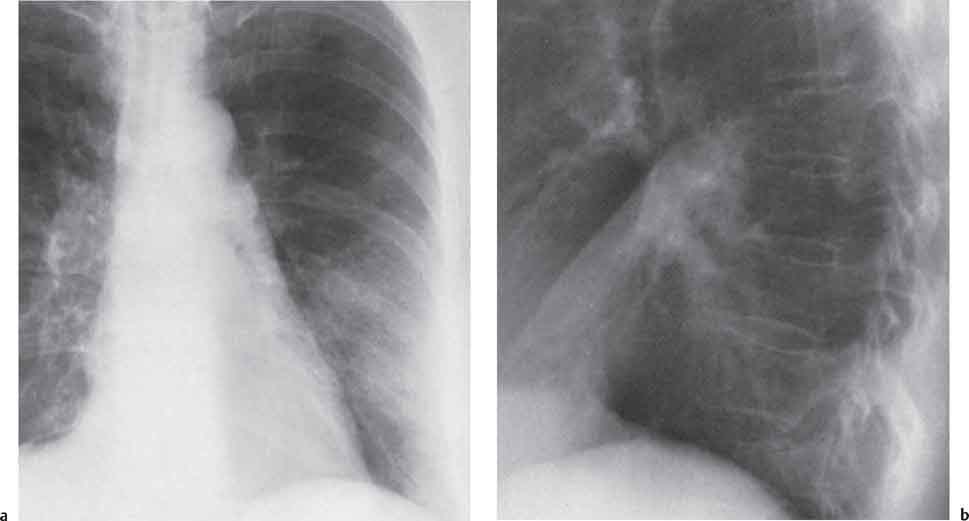

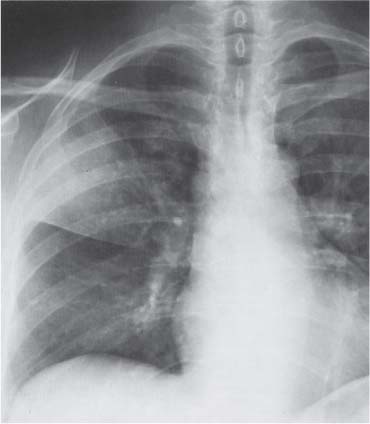

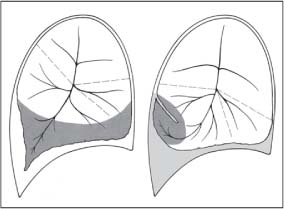

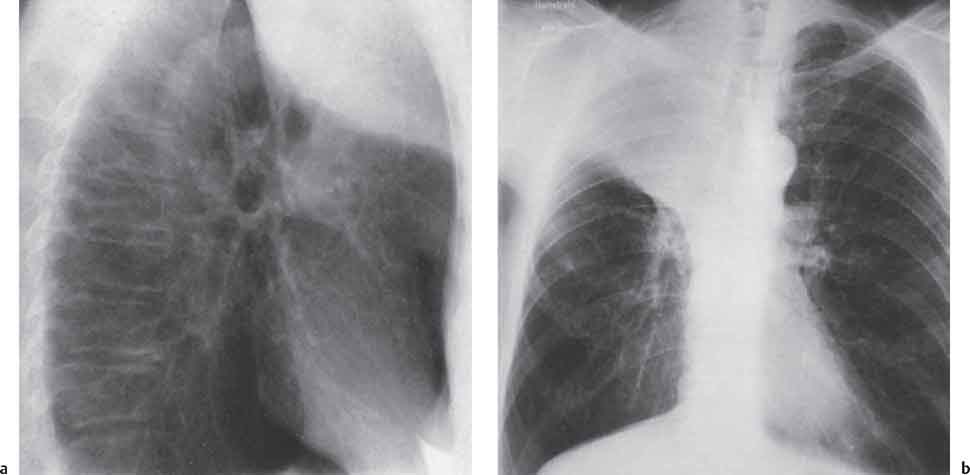

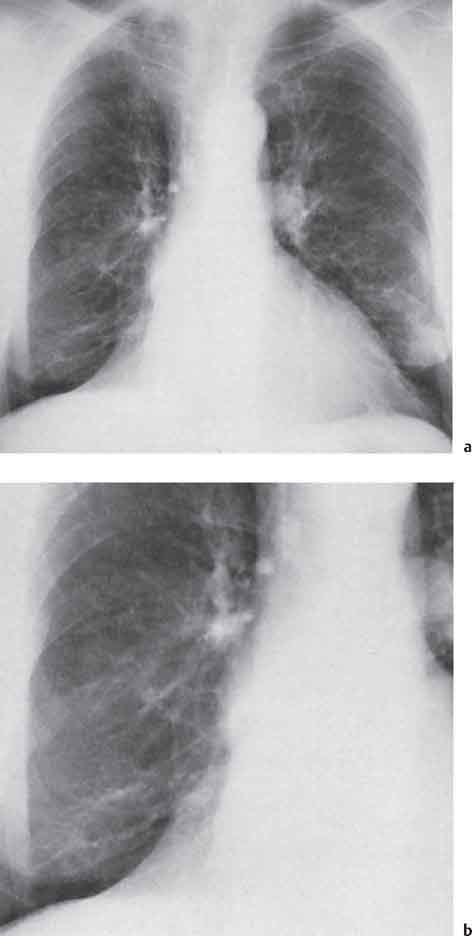

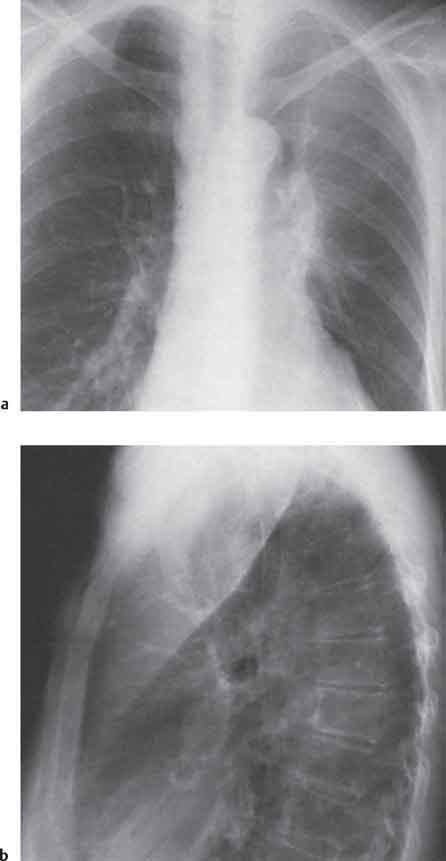

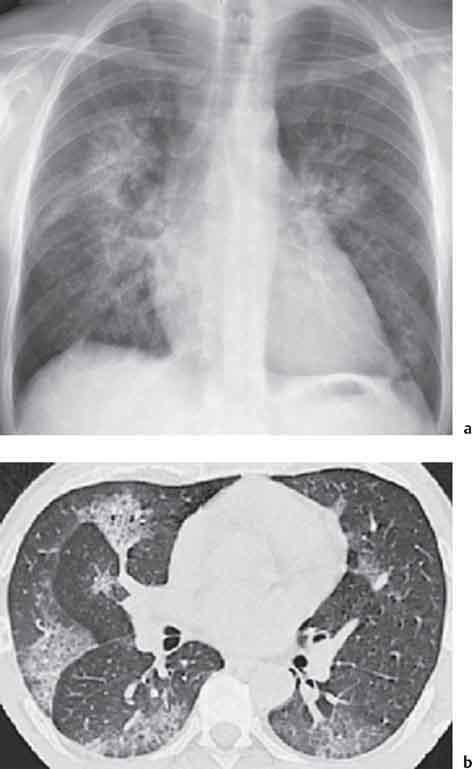

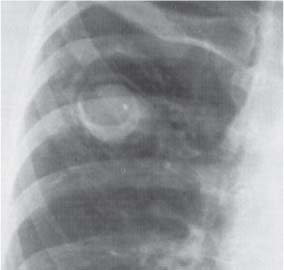

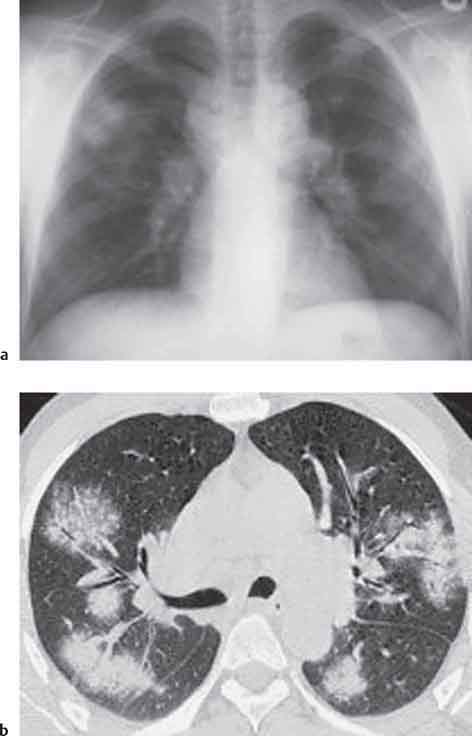

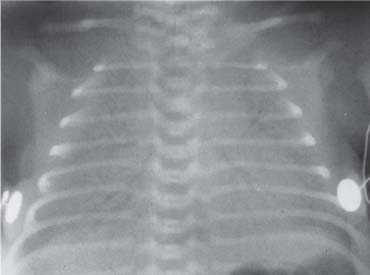

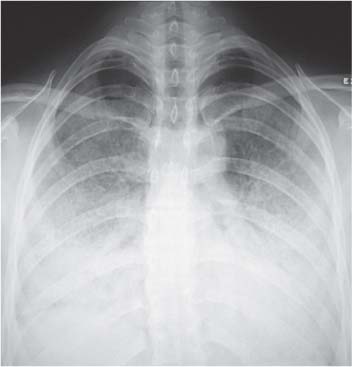

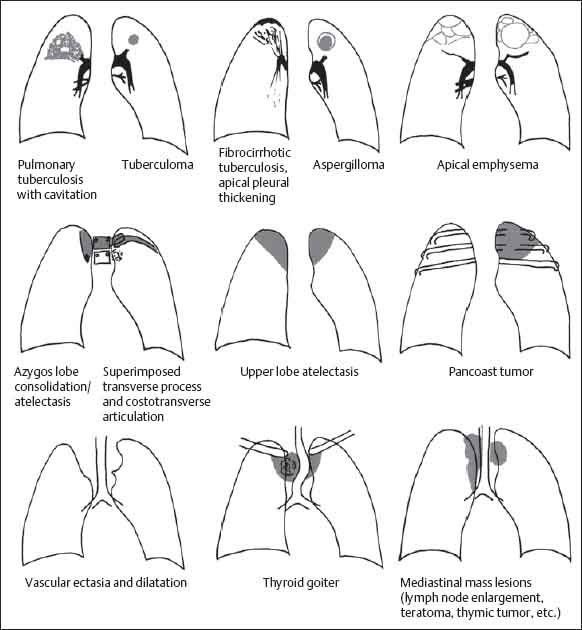

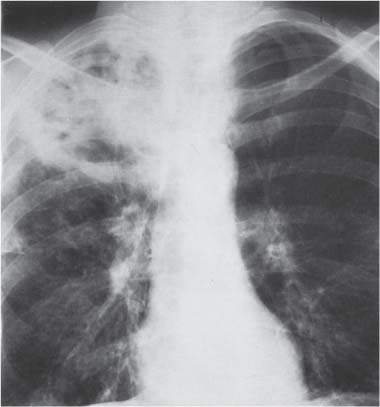

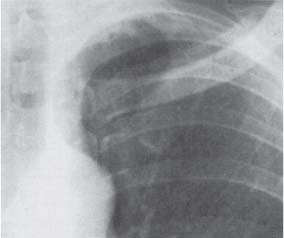

13 Radiographic Signs and Differential Diagnosis Complete opacification of a hemithorax frequently indicates the presence of significant disease. The differential diagnosis includes: The chest radiograph shows the opaque hemithorax, any associated mediastinal displacement, and occasionally may suggest the correct diagnosis. Computed tomography (CT) ± bronchoscopy are standard 2nd line investigations for further assessment. Comparison of the volume of the opaque hemithorax to that of the unaffected side is important when considering the differential diagnosis (Fig. 13.1): Table 13.1 The opaque hemithorax Fig. 13.1 The opaque hemithorax. Fig. 13.2 Right lung atelectasis secondary to central bronchial carcinoma. There is occlusion of the right main bronchus and ipsilateral mediastinal displacement. On upright views, the opacification is particularly marked in the laterobasal hemithorax with blunting of the costophrenic angles. The effusion may be mobile with changes in patient position. Empyema, tuberculous effusion, and hemothorax may resolve leaving marked fibrous pleural thickening. This may lead to severe pulmonary encasement with resulting ventilatory impairment. An opaque hemithorax in pleural neoplasia may be due to the presence of an effusion and/or pleural tumor. Marked encasement of the underlying lung with resulting atelectasis may lead to a decrease in the size of the hemithorax. Complete pulmonary atelectasis results from occlusion of a main bronchus by carcinoma or less commonly by an aspirated foreign body, mucus plug, stricture, or bronchial tear. The volume of the hemithorax is reduced and there is ipsilateral mediastinal displacement (Fig. 13.2). A concomitant pleural effusion, however, may restore thoracic symmetry (Fig. 13.3). It is rare for pneumonic infiltration to involve the entire lung. A well-penetrated chest radiograph may show small residual areas of normal lung and air-filled bronchi traversing the consolidation (air bronchogram). The diagnosis is supported by clinical findings of cough, sputum production, pyrexia, and leukocytosis, and by identifying the causative organism in sputum samples or from blood cultures. Tuberculous pneumonia very occasionally may involve the entire lung in children. Computed tomography in such cases will usually reveal areas of cavitation ± features of endobronchial spread. The involved hemithorax is small and there is ipsilateral mediastinal displacement (see Chapter 2, p. 58) (Fig. 13. 4). Extreme scoliosis with posterior unilateral rib prominence and thoracic deformity can occasionally mimic an opaque hemithorax, particularly on underexposed views. This appearance may be accentuated by the secondary ventilatory restriction and pulmonary underexpansion seen in some of these cases. Fig. 13.4 Left pneumonectomy: Chest radiograph shows opaque left hemithorax with ipsilateral mediastinal displacement. The lung is subdivided into functional anatomic units and some pathologic processes tend not to transgress lobar and/or segmental boundaries. Lobar/segmental opacification may be patchy or confluent depending on the volume of residually aerated lung. Opacification may be due to consolidation or atelectasis. Occasionally, overlying pleural or chest wall lesions may mimic segmental opacification. The commonest cause of lobar/segmental opacification is acute pneumonia. This can usually be diagnosed from the clinical history and characteristic radiographic appearances; these tend to resolve within days of commencing appropriate antibiotic therapy. Diagnosis becomes more difficult and merits further evaluation when radiographic abnormality persists. Bronchial carcinoma is a frequent cause of persistent atelectasis and/or consolidation, particularly in older individuals from “at risk” categories (see Chapter 6, p. 157). Bronchial obstruction by mucus plugs, foreign bodies, and benign tumors are less common causes of persistent lobar/segmental opacification. Pulmonary infarction may also lead to segmental opacification which is slow to resolve (see Chapter 7, p. 189). Loculated pleural effusions, interlobar effusions, chest wall tumors, and large pulmonary angiomata and tumors occasionally mimic segmental opacities in their shape and location but they never have an air bronchogram or alveologram. An inflammatory or neoplastic process may spread within the alveolar spaces of a segment until it reaches the segmental or lobar boundary. Aerated lung is replaced by fluid and cellular infiltrate. Residually aerated alveoli may appear as small “foamy” lucencies (positive air alveologram) and residual air within the bronchi forms a pattern of branching radiolucent channels (positive air bronchogram) within the consolidation. Usually the anatomic shape of the segments remains unchanged although a slight volume increase can occur in entities such as Klebsiella pneumonia producing a convex border with the adjacent normal lung. Table 13.2 Lobar and segmental opacification Acute Lobar and Segmental Pneumonia Classic lobar pneumonia caused by pneumococci or Klebsiella pneumoniae has become a rarity. Because bacterial pneumonia spreads from alveolus to alveolus through the pores of Kohn, lobar and segmental boundaries create a reasonably effective barrier. Because of this, the opacity exhibits at least one sharp border, even if the consolidation does not involve the entire segment (peripheral consolidation). Tuberculous Pneumonia Tuberculous pneumonia has a predilection for the upper lobes and the apical segments of the lower lobes. Often there are accompanying features of past tuberculosis such as apical pleural thickening and fibrocirrhotic changes in the apical parenchyma. Any upper lobar segmental opacity persisting for weeks should raise suspicion of tuberculous pneumonia, particularly in at-risk groups of individuals. Bronchioloalveolar Carcinoma Some bronchial carcinomas, especially those of bronchioloalveolar type, spread within the alveoli of a lung lobe or segment and may be indistinguishable from pneumonic consolidation. Fig. 13.5 CT coronal reformat shows partial right lower lobe consolidation with loss of definition of the right hemidiaphragm. Fig. 13.6 Right upper lobe consolidation with a minor degree of associated atelectasis leading to slight superior displacement of the right minor fissure. Fig. 13.7a, b Pneumonic consolidation involving the anterobasal left lower lobe. Pulmonary Infarction Pulmonary infarcts appear as subtle segmental opacities which occur predominantly in the subpleural lung of the lower lobes. Left ventricular failure usually is a prerequisite for the development of infarction following pulmonary embolism. Fig. 13.8a, b Right middle lobe pneumonia. The right heart border is not visualized. Fig. 13.9 Pneumonic consolidation involving the anterior segment of the right upper lobe lies adjacent to the minor fissure. Fig. 13.10a, b Right middle lobe pneumonia. Volume loss in a lobe tends to have a specific radiographic appearance (Fig. 13.12): Atypical appearances may be due to collateral aeration of isolated boundary zones or may occur in cases where fibrous adhesions prevent uniform volume loss. Fig. 13.11 Evolution of round atelectasis (from Hanke and Kretschmar 1983). Complete atelectasis appears radiographically as a homogeneous shadow but initially some portions of the segment may still be aerated. The following radiographic features characterize atelectasis: Fig. 13.12 Lobar atelectasis. Fig. 13.13a, b Right upper lobe consolidation and atelectasis due to endobronchial tumor. There is superior displacement of the right minor fissure and the major fissure is displaced anteriorly. Fig. 13.14 Right upper lobe atelectasis due to an endobronchial mucus plug. Fig. 13.15a, b Right lower lobe atelectasis. There is opacification of the right cardiophrenic angle with “loss” of the right hemidiaphragm. Fig. 13.16a, b Left upper lobe atelectasis secondary to central bronchial carcinoma. Central Bronchial Carcinoma Lobar or segmental atelectasis may be associated with ipsilateral hilar enlargement ± mediastinal lymph node enlargement. Endobronchial Metastases Breast carcinoma and other tumors occasionally metastasize to the wall of a lobar or segmental bronchus (see Fig. 6.34 a, b). Benign Endobronchial Tumors Bronchial carcinoid is the most common benign tumor to display endobronchial growth and lead to distal atelectasis. A small number of cases will develop bronchoceles distal to the obstructing tumor and branching opacities may then be the predominant radiographic finding. Other endobronchial tumors including chondroma, which occasionally shows flocculent calcification, hamartomas, and amyloid tumors are comparatively rare. Endobronchial Mucus Plugging This is characteristically seen in severe asthma and in patients with superimposed Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis (ABPA). Bronchial Rupture and Hematoma Severe thoracic injuries may rupture a main or lobar bronchus with submucosal hematoma and distal atelectasis. Inflammatory bronchial strictures may be seen in entities such as tuberculous infection and Wegener’s granulomatosis. The right middle lobe bronchus is particularly susceptible to compression by adjacent tuberculous lymph nodes resulting in distal atelectasis. These are poorly-defined nonsegmental areas of consolidation which may contain air broncho- and air alveolograms. The commonest cause of nonsegmental consolidation is bronchopneumonia, which is readily diagnosed when classic presentation is combined with radiographic findings of patchy or confluent air space consolidation. Acute Bronchopneumonia This disease is characterized by patchy air space shadowing characteristically involving the mid-to-lower lung zones. Acute bronchopneumonia is usually due to bacterial infection (Fig. 13.17). Table 13.3 Pulmonary opacification not conforming to lobar and segmental boundaries Aspiration pneumonia characteristically involves the dependent portions of the lung, most commonly the lower lobes. Right lung involvement is more frequent due to the more vertical course of the bronchus intermedius. Aspiration pneumonia may be complicated by pulmonary abscess formation. Tuberculous Pneumonia Multifocal areas of bronchocentric consolidation may be a manifestation of endobronchial spread of tuberculosis and there may be associated micronodular shadowing consistent with a cellular bronchiolitis Fungal Pneumonia Fungal pneumonias and particularly semi-invasive aspergillosis (Fig. 13.18) in older individuals with a mild degree of immunocompromise due to comorbidities may manifest as patchy air space consolidation. Pulmonary Edema Early-stage alveolar edema may have an inhomogeneous patchy distribution in the mid-to-lower lung zones. There are characteristically features of associated interstitial edema with peribronchial cuffing and interlobular septal thickening. Pulmonary Contusion Patchy, confluent opacities representing sites of intra-alveolar edema and hemorrhage are seen in the traumatized lung. Pulmonary contusions typically resolve in 3 to 6 days except when infection supervenes. Pulmonary Hemorrhage Diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage is associated with underlying disease entities including Antiglomerular Basement Membrane Disease (AGBMD) and Wegener’s Granulomatosis. Initial multifocal opacification in a peribronchovascular distribution may progress to areas of confluent consolidation. Churg-Strauss Allergic Granulomatosis Chest radiographs may show transient, recurrent pneumonic infiltrates in addition to pericardial and pleural effusion in patients with this systemic necrotizing vasculitis. Pulmonary Neoplasia Both bronchioloalveolar carcinoma and pulmonary lymphoma may be manifest radiographically as patchy air space consolidation in a peribronchial distribution. Radiation Pneumonitis and Fibrosis Air space consolidation characteristically conforms to the radiation portal in radiotherapy-induced pneumonitis. Consolidation over time may organize leaving some degree of interstitial fibrosis (Fig. 13.19). Fig. 13.17a, b Multifocal airspace consolidation not conforming to segmental or lobar boundaries. Fig. 13.18 Aspergilloma: Mycetoma with air crescent is seen within right upper lobe cavity. Fig. 13.19 a–c Radiotherapy-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Chest radiograph (a) shows right-sided pulmonary opacification not conforming to lobar or segmental boundaries. Patchy sclerosis in the proximal diaphysis of the right humerus is characteristic of old bone infarct. Axial CT image displayed at lung windows (b) shows pulmonary change consistent with fibrosis in the right upper zone. CT displayed at bony windows (c) shows bone infarct in right proximal humerus. Sarcoidosis (Fig. 13.20) See Chapter 3, p. 91. Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome See Chapter 8, p. 208. Fig. 13.20a, b Sarcoidosis. The chest radiograph (a) shows bilateral hilar and mediastinal lymph node enlargement with areas of pulmonary consolidation. CT shows bilateral hilar and mediastinal lymph node enlargement with areas of consolidation consistent with the “alveolar” variant of sarcoidosis. Fig. 13.21a, b Pleural effusions in supine patient: Hazy opacification of both hemithoraces on AP supine projection (a) is due to bilateral pleural effusions and underlying pulmonary atelectasis (b). Fig. 13.22 Hyaline membrane disease with bilateral “ground-glass opacification” in a preterm infant. Air bronchograms are visible. Fig. 13.23 Adult respiratory distress syndrome in acute pancreatitis. Initial chest radiograph shows diffuse, bilateral pulmonary opacification. Fig. 13.24 Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema in a patient with renal impairment. Fig. 13.25 Alveolar proteinosis. Chest radiograph shows “hazy” opacification of both lungs with associated interstitial thickening in patient with alveolar proteinosis. Opacification of the lung apex and upper paramediastinal lung may be due to pulmonary, pleural, or mediastinal disease. Pulmonary diseases showing a predilection for the upper lobe include tuberculosis, ABPA, and pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis (PLCH). Superior mediastinal widening may be due to vascular ectasia, thyroid goiter, or mediastinal lymph node enlargement. Vascular Ectasia Ectasia of superior mediastinal vessels leads to mediastinal widening with a curved, sharply defined lateral border. Dilatation and elongation are particularly common in elderly patients and may involve the left brachiocephalic vein, subclavian vein, superior vena cava, and innominate artery. Computed tomography will confirm the vascular ectasia when there is diagnostic uncertainty. Fig. 13.26 Upper zone opacification. Table 13.4 Upper zone and apicomediastinal angle opacification Aortic/Great Vessel Aneurysm Aneurysmal dilatation of the aortic arch may produce a large mediastinal density, generally with a convex lateral border on the posteroanterior (PA) chest radiograph (see also Chapter 11, p.283). Aneurysmal dilatation of a subclavian/anomalous right subclavian artery may lead to unilateral superior mediastinal widening. Retrosternal Goiter and other Mediastinal Soft Tissue Lesions There is widening of the superior mediastinum and the trachea may be narrowed or displaced. Thyroid nodules may show flocculent calcification. See also Chapter 11, p. 285. Upper Lobe Pneumonia Pneumonia involving the apical segment of the right upper lobe or the apicoposterior segment of the left upper lobe appears as a triangular paramediastinal opacity. Consolidation in the anterior segment of the right upper lobe abuts the minor fissure. Upper Lobe Tuberculosis (Fig. 13.27) Tuberculous infection should be excluded in all cases of persisting upper lobe consolidation (see also Chapter 3, p. 72). Fig. 13.27 Right upper lobe tuberculosis. Fig. 13.28 Radiation pneumonitis posttreatment of left hilar/ upper lobe bronchial carcinoma. Fig. 13.29 Apical pleural thickening. Bronchial Carcinoma Bronchial carcinomas may occur in the superior sulcus of the lung and infiltrate locally (Pancoast tumor). The chest radiograph may demonstrate destruction of adjacent ribs. More commonly, bronchial carcinoma arising from and occluding the upper lobe bronchus leads to distal upper lobe consolidation and atelectasis (Fig. 13. 28). Silicosis Silicotic nodules sometimes may be concentrated in the upper lobes. Progressive massive fibrosis (PMF) complicating silicosis has a marked predilection for the upper lobes. Pulmonary Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis Early-stage nodular PLCH characteristically involves the upper-to-mid zones with relative sparing of the lung bases (see also Chapter 6, p. 154). Mucoid Impaction (Bronchocele Formation) Congenital bronchial atresia occurs most commonly in the apicoposterior segmental bronchus of the left upper lobe. The airway distal to the atresia is dilated and filled with mucus and appears as an elongated, partially branched opacity in the left upper lobe (bronchocele). Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis also leads to mucus plugging of bronchi and characteristically colonizes dilated upper lobe bronchi. Fig. 13.30 Pleural line associated with an azygos lobe. Apical Pleural Thickening An apical pleural peel may extend to involve the mediastinal pleura and reach a thickness of several millimeters (Fig. 13.29). Azygos Lobe and Fissure

1. The Opaque Hemithorax (Table 13.1)

Diagnostic Approach

Differential Diagnosis

Pleural Effusion

Pleural Thickening and Fibrothorax

Pleural Mesothelioma and Metastatic Pleural Carcinomatosis

Atelectasis

Pneumonia

Tuberculosis (TB)

Pulmonary Aplasia, Agenesis, and Pneumonectomy

Thoracic Scoliosis and Chest Wall Deformity

2. Lobar and Segmental Opacification

Diagnostic Approach

Differential Diagnosis (Table 13.2)

Pseudosegmental Opacities

Lobar and Segmental Consolidation

Lobar and segmental consolidation

Atelectasis:

Absorption atelectasis

Relaxation atelectasis

Pseudosegmental opacities

Lobar and Segmental Atelectasis

Inflammatory Bronchial Strictures and Extrinsic Compression

3. Opacification which does not Conform to Anatomic Boundaries

Inhomogeneous and Regionally Confluent Air Space Opacification

Diagnostic Approach

Differential Diagnosis (Table 13.3)

Inflammatory

Edema and hemorrhage

Neoplastic

Miscellaneous

Bilateral symmetric opacification

Bilateral Symmetric Hazy Opacification

Differential Diagnosis

4. Opacification involving the Upper Zone and/or Apicomediastinal Angle

Diagnostic Approach

Differential Diagnosis (Fig. 13.26, Table 13.4)

Vascular and Mediastinal Lesions

Mediastinal

Vascular

Nonvascular

Pulmonary and Pleural

Miscellaneous

Pulmonary and Pleural

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree