In this review article, the authors discuss the imaging features of the most common pathologic conditions of the wrist by putting the emphasis on radiographic and MR imaging correlations. A topographic approach based on the 3 functional columns of the wrist (radial, central, and ulnar) serves as a framework. The pathologic conditions are classified, based on the structures involved, as fractures, ligament injuries, arthropathies, bone abnormalities, and tendinopathies. The authors describe and evaluate classic radiographic signs and explain how they correlate with MR imaging. The advantages and limitations of each technique are thoroughly discussed as well as other imaging modalities.

Key points

- •

The wrist can be divided into 3 functional columns (radial, central, and ulnar) as a practical way to discuss the different pathologic conditions.

- •

There is a synergy between radiographs and MR imaging that complements the diagnosis of these pathologic conditions; it is important to understand the advantages and limitations of each modality.

- •

Radiographically occult fractures of the wrist (eg, distal radius, scaphoid, hook of the hamate) are common, and the imaging strategy has evolved over the years thanks to a greater availability of MR imaging and multidetector computed tomography.

- •

Avascular necrosis of the carpal bones (eg, scaphoid and lunate) poses specific diagnostic and therapeutic difficulties.

Introduction

The wrist is one of the most complex articular structures in the human body owing to its multiple constitutive bones and intricate joints. This complexity makes it difficult to assess radiologically and stresses the importance of using an adequate imaging technique and a thorough systematic analysis of the images to reach the correct diagnosis.

In this article, the authors focus on the correlation between radiographs and MR imaging. Because MR imaging is now routinely obtained in the workup of wrist symptoms, the interpretation of subtle radiographic findings has been refined, and these will be emphasized here. There are also circumstances whereby MR images can be misleading when not analyzed together with the radiographs.

The three columns of the wrist

On a biomechanical point of view, the wrist is commonly divided into 3 functionally distinct columns ( Fig. 1 ). This approach is also valuable to narrow the differential diagnosis based on the location of the clinical symptoms and to ascertain that a specific anatomic area has been adequately investigated with the imaging protocol.

The lateral or radial column encompasses the scaphoid fossa and radial styloid: the scaphoid, the trapezium, the trapezoid, and the bases of the first and second metacarpals. In addition to the standard posteroanterior (PA) and lateral views, these bones are best demonstrated with dedicated radiographic views, including the semipronated oblique view, the scaphoid views, as well as the Kapandji views of the thumb. The pathologic conditions of the lateral column of the wrist are summarized in Table 1 .

| Bones |

|

| Joints |

|

| Ligaments |

|

| Tendons |

|

| Nerves |

|

The medial or ulnar column contains the distal ulna and ulnar styloid, the medial aspect of the lunate, the triquetrum, the pisiform, the hamate, and the bases of the fourth and fifth metacarpals. A thorough analysis of these bones may require additional specific radiographic views, such as the semisupinated view, and the carpal tunnel view for the hook of hamate. The pathologic conditions of the medial column of the wrist are summarized in Table 2 .

| Bones |

|

| Joints |

|

| Ligaments |

|

| Tendons |

|

| Nerves |

|

The central column of the wrist includes the rest of the bone structures, namely, the lunate fossa of the radius, the lunate, the capitate, and the base of the third metacarpal. Additional oblique semipronated and semisupinated views may be helpful; these bones are often difficult to assess on radiographs because of their central position with many overlapping structures. The pathologic conditions of the medial column of the wrist are summarized in Table 3 .

| Bones |

|

| Joints |

|

| Ligaments |

|

| Tendons |

|

| Nerves |

|

Imaging protocols

Wrist Radiographs

A recommended routine radiographic protocol for the wrist includes the PA, lateral, oblique semipronated, and oblique semisupinated views.

In an appropriate clinical context, this protocol can be supplemented with the ligamentous instability series, including additional PA views in radial and ulnar deviations and a PA view with a clenched fist. Selected views of the scaphoid and carpal tunnel can also be useful in specific circumstances.

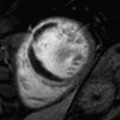

Wrist MR Imaging

A routine protocol typically includes a combination of T1-weighted and fat-suppressed T2- or intermediate-weighted sequences in the coronal, transverse, and sagittal planes. A dedicated wrist coil is required in order to obtain an optimal image quality with adequate signal-to-noise ratio and spatial resolution. The section’s thickness is routinely set between 2 and 3 mm. Contiguous thinner sections or even isotropic submillimetric acquisition can be obtained with 3-dimensional gradient-echo or spin-echo sequences and may be useful for the evaluation of ligaments and cartilage. In the authors’ institutions, computed tomography (CT) arthrography and occasionally MR arthrography are still favored for the evaluation of wrist ligaments and cartilage abnormalities.

Radial column of the wrist

Helpful Radiographic Signs and Pitfalls

The scaphoid and pronator quadratus fat stripes

The normal scaphoid fat pad is located between the radial capsule and the abductor longus and the extensor brevis tendons ( Fig. 2 ). It appears as a thin linear or triangular lucency adjacent to the scaphoid on the PA view. Its obliteration may indicate a scaphoid fracture.

The pronator quadratus fat pad is seen on the lateral view of the wrist as a thin lucent area superficial to the opacity of the pronator quadratus muscle. Its obliteration can be seen in the presence of distal radius fractures.

In a recent study, it was observed that these signs are not really reliable and had sensitivity and specificity values of only 50% and 50%, respectively, for the scaphoid fat stripe, and 26% and 70%, respectively, for the pronator fat stripe.

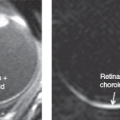

The scaphoid cortical ring sign

It corresponds to the end-on view of the scaphoid tubercle when the scaphoid is flexed ( Figs. 3 and 4 ). Because a flexed scaphoid can be normal, the value of this sign depends on the position of the other carpal bones, mainly the lunate. The association of an abnormally extended lunate with a flexed scaphoid manifests as an increased scapholunate angle over 70° (normal values 30°–60°) and indicates scapholunate dissociation, usually associated with a complete scapholunate ligament tear.

Fractures

Scaphoid fractures

Fractures of the scaphoid are the second most frequent fracture of the wrist after the distal radius and represent 70% of carpal fractures. They involve, by decreasing order of frequency, the waist (70%), the proximal pole (20%), and the distal tubercle (10%) of the scaphoid.

It is estimated that radiographs allow the diagnosis of only 40% to 60% of these fractures, leaving a large proportion undetected. The strategy to demonstrate radiographically occult scaphoid fractures has evolved over the years from immobilization and follow-up radiographs to bone scintigraphy, and finally, early MR imaging or multidetector computed tomography (MDCT). Both MR imaging and CT with submillimetric collimation have a sensitivity of nearly 100% for the detection of scaphoid fractures with cortical involvement. The high sensitivity of MR imaging for recent fractures is due to the fact that the fracture line is highlighted by bone marrow edema ( Fig. 5 ). However, there is a potential for false positives, corresponding to purely trabecular fractures or bone bruises.

Other fractures

Fractures of the distal radius are the most frequent fractures of the wrist, and about 20% are radiographically occult ( Fig. 6 ). Fractures of the trapezium and base of the first metacarpal fractures are seen less frequently.

Ligament Injuries

Scapholunate ligament tear

The scapholunate ligament is the primary stabilizer of the scapholunate joint, and tears may occur following a fall on an outstretched hand. Disruption of this ligament and the secondary stabilizers (dorsal and palmar capsular ligaments) releases the natural tendency of palmar flexion for the scaphoid and dorsal flexion for the lunate, which results in a scapholunate dissociation.

Scapholunate dissociation manifests on radiographs as a scapholunate diastasis on the PA view and an increased scapholunate angle over 70° (normal 30°–60°) on the lateral view (see Fig. 3 ). As a general rule, measuring carpal angles on CT and MR images should be avoided because of a different position of the wrist causing unreliable values. However, the scapholunate angle appears relatively independent of the wrist position and demonstrates a low variability between different modalities.

Scapholunate ligament tears are well demonstrated with MR imaging when they are complete (see Fig. 3 ). However, its sensitivity is insufficient for partial tears that are better demonstrated with MR arthrography or CT arthrography.

Scapholunate ligament cyst

The dorsal aspect of the wrist is one the most common locations for ganglion cysts, where they can be seen in an area recently known as the dorsal capsuloscapholunate septum. A nonspecific bulge of the dorsal soft tissues may be noted on radiographs if the cyst is large. The diagnosis is more straightforward with ultrasound (US) or MR imaging ( Fig. 7 ).

Arthropathies

Trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis at the base of the thumb is common with aging and regularly associated with osteoarthritis of the hand. It is a frequent cause of pain and disability at the radial aspect of the wrist. It can be treated by arthroplasty or excision of the trapezium with good results ( Fig. 8 ).

Radioscaphoid osteoarthritis

Occurrence of degenerative changes between the radius and the scaphoid is the consequence of an altered kinematic of the intercalary segment and particularly the scaphoid. The scapholunate advanced collapse (SLAC-wrist) is a complication of scapholunate ligament tear and scapholunate dissociation, where rotatory subluxation of the scaphoid causes progressive cartilage damage. Different stages of osteoarthritis starting between the distal radius and scaphoid, and extending to the capitolunate space, have been described ( Table 4 ). In absence of traumatic history, calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition disease is another cause of SLAC-wrist (see Fig. 4 ). Similarly, a pattern of scaphoid nonunion advanced collapse (SNAC-wrist) complicating scaphoid fractures has been described ( Fig. 9 , Table 5 ). Treatment options include proximal row carpectomy, scaphoid excision with 4-corner arthrodesis, or total wrist arthrodesis depending on the stage and need for grip strength.

| Stage 1 | Osteoarthritic changes limited to the radial styloid |

| Stage 2 | Osteoarthritic changes extending to the whole scaphoid fossa of the radius |

| Stage 3 | Proximal migration of the capitate with osteoarthritic changes between the capitate and lunate |

| Stage 1 | Osteoarthritic changes limited to the radial styloid |

| Stage 2 | Osteoarthritic extending between the distal scaphoid and capitate |

| Stage 3 | Osteoarthritic changes between the capitate and lunate |

Bone Abnormalities

Avascular necrosis of the scaphoid

Because the scaphoid is covered with cartilage over 75% of its surface, most of its vascularization derives from a branch of the radial artery entering the bone at the level of the waist and following a retrograde intraosseous path. Avascular necrosis complicates 13% to 50% of scaphoid fractures depending on their location (risk is high for the proximal third, moderate for the middle third, and low for the distal third) and displacement. Coexistence with fracture nonunion is common, albeit occurrence of avascular necrosis after fracture consolidation has been described. There is also an uncommon nontraumatic avascular necrosis of the scaphoid known as Preiser disease ( Fig. 10 ).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree