Renal Cystic Disease

Renal cysts, cystic disease, and cystic masses are the most common abnormalities encountered in uroradiology. In some patients, renal cysts are part of a systemic process that also involves the kidneys. In most patients, however, one or several cystic masses are detected, and the radiologist must determine whether a particular cystic mass is benign or malignant. In most patients, the radiographic findings are sufficiently characteristic that surgery is not required. However, an examination designed specifically to examine a renal mass may be necessary before a confident diagnosis can be reached.

▪ CORTICAL CYSTS

Simple Cysts

The most common renal mass is a simple cortical cyst. Cortical cysts are uncommon in children or young adults but are detected in the older population routinely on computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and ultrasonography (US) examinations. In fact, renal cysts have been estimated to occur in 50% of the population older than 50 years. Thus, they are considered acquired lesions.

Simple cysts are composed of fibrous tissue and are lined by flattened cuboidal epithelium. They contain clear serous fluid and do not communicate with the collecting system. The precise etiology of simple cysts is not known; it is proposed that they occur as a result of tubular obstruction such that the tubule no longer communicates with the nephron. Cysts arise from the distal convoluted tubule or collecting duct and are lined by flattened epithelial cells.

Most patients with simple cysts are asymptomatic, and the cysts are detected as incidental findings. Hematuria is occasionally attributed to a benign cyst, but cysts actually bleed so infrequently that other lesions must be sought in patients with hematuria. Rarely a large simple cyst may obstruct the collecting system or cause hypertension. Local pain may be attributed to distention of the cyst wall or spontaneous bleeding into the cyst; however, the vast majority of cysts are asymptomatic. Occasionally, a simple cyst may become infected.

Although simple cysts have been described in all age groups, they are unusual in children. A cyst in a child must be carefully examined to differentiate a benign cyst from a cystic Wilms tumor. A cyst in a child may also be an early sign of a cystic nephropathy.

A cortical cyst can occasionally be detected on an abdominal radiograph. The water-density cyst is seen as a cortical bulge projecting into the perinephric fat. Calcification is seen in the wall of a cyst in only approximately 1% of cases. If the calcification is thin and border forming, the lesion is likely to be a benign, complicated cyst.

During excretory urography, a simple cyst is seen as a lucent mass in the renal parenchyma. Radiographs obtained soon after intravenous contrast medium injection (1 or 2 minutes) optimize visualization of renal cortical masses, because this is the peak of parenchymal opacification. A cyst is well defined and has a sharp interface with the normal renal cortex. The cyst does not enhance but may distort the adjacent parenchyma. If the cyst extends beyond the surface of the kidney, the parenchyma is extended to produce a “beak” or “claw sign.” The margin of the cyst with the kidney is smooth, and the cyst wall is too thin to be seen during urography. If the cyst is entirely intrarenal, its wall cannot be distinguished from the adjacent renal parenchyma and its thickness cannot be assessed. Exophytic cysts that displace perinephric fat instead of renal parenchyma may appear relatively dense at excretory urography.

IMAGING FEATURES OF A SIMPLE CYST ON CT

Round, homogenous mass

Sharp, well-marginated interface with normal parenchyma

Near water attenuation (0-20 Hounsfield units [HU])

Thin, smooth wall that often is imperceptible

No calcifications or septations

No enhancement after contrast medium administration

These same findings are present on CT examination. CT has superior contrast resolution, allowing measurement of the density of the cyst fluid, which should approximate that of water. Renal cysts are often detected as incidental findings during contrast-enhanced CT examinations of the abdomen, and there is no opportunity to test for contrast enhancement. However, if the density of the cyst fluid is less than 20 HU and other criteria of a simple cyst are present, the lesion will almost certainly be benign.

The wall of a benign simple cortical cyst is often too thin to be seen on CT, but a pencil-thin, smooth wall may be seen. When evaluating wall thickness with CT, it is important to evaluate the portion of the cyst that extends well away from the parenchyma so that a portion of adjacent renal tissue (beak) is not included in the section. If the cyst is completely intrarenal, wall thickness cannot be assessed.

Corresponding features are also seen on ultrasound examinations. A simple cyst is a round homogeneous mass with a sharp interface with the normal renal parenchyma. A simple cyst is echofree with enhanced through transmission. Thin septations that are too fine to be detected with CT may be seen with ultrasound.

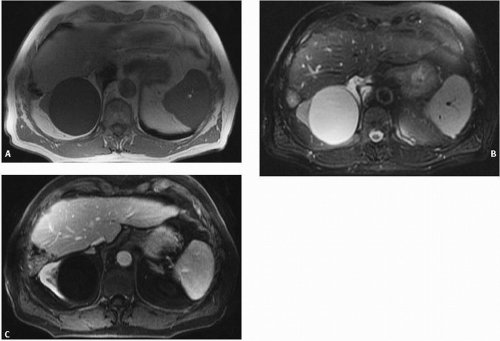

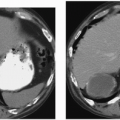

Cysts may be seen with renal scintigraphy as photopenic regions because of the displacement of functioning parenchyma by the cyst. If the cyst is small or exophytic, scintigraphy may be normal. Parapelvic cysts, or cortical cysts that extend centrally into the renal sinus, may cause photopenic regions in the renal sinus that mimic hydronephrosis. The correct diagnosis is reached if the isotope can be identified in the ureter, even though the photopenic region persists. Simple cortical cysts are readily detected with MRI (Fig. 7.1A-C). The appearance of a homogeneous round mass with a thin, smooth wall and sharp interface with normal renal parenchyma is similar to that on CT. The long T1 values result in a lowsignal intensity on T1-weighted images. However, they have a very high-signal intensity on T2-weighted images, which reflects the long T2 value of water.

IMAGING FEATURES OF A SIMPLE CYST ON US

Round, homogeneous mass

Sharply marginated

Anechoic

Enhanced through transmission

The accuracy of the radiographic diagnosis of a renal cyst depends on how well it is seen with each modality. When all of the criteria of a benign simple cyst are present, it is highly unlikely to be anything else and further evaluation is not warranted. However, cysts are often not visualized well enough by excretory urography to make this determination. Because of cost considerations, ultrasound is the most efficient method of confirming the presence of a simple cyst seen during excretory urography. Ultrasound has the added advantages of not requiring ionizing radiation and avoiding the potential adverse reactions associated with intravenous contrast medium injection.

IMAGING FEATURES OF A SIMPLE CYST ON MRI

Round, homogeneous mass

Sharply well-marginated interface with normal parenchyma

Low-signal intensity on T1-weighted images

High signal on T2-weighted images

Thin, smooth wall that often is imperceptible

No enhancement after contrast medium administration

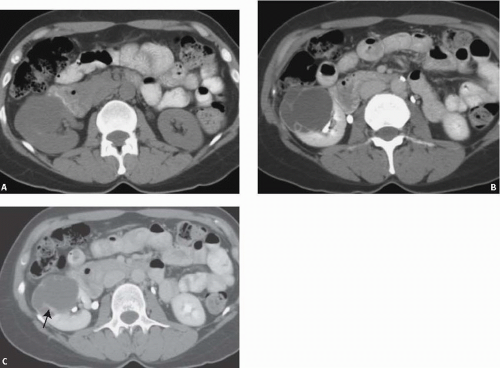

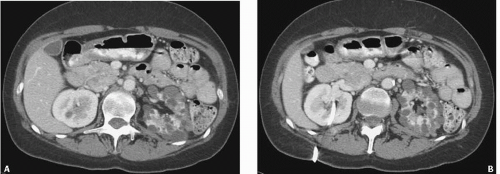

FIGURE 7.2. Unilateral cystic disease. Nephrographic (A) and excretory (B) phase CT images show multiple left renal cysts and a normal right kidney. A right-sided percutaneous nephrostomy is present. |

CT is the gold standard for the evaluation of renal masses, but it is a more expensive examination than ultrasound, requires intravenous contrast medium, and exposes the patient to ionizing radiation. It is indicated when an ultrasound examination is indeterminate or is technically inadequate due to the patient’s obesity or overlying bowel gas. It is also appropriate to proceed directly to CT if the excretory urogram indicates that the mass is complex (not simple) or likely to contain solid portions. MRI is used in patients with a contraindication to the use of intravenous contrast medium, or if after the CT scan, the nature of the cystic mass is still in question. Although typically more expensive and not as widely available, MRI may also be utilized in lieu of CT, particularly in young patients in whom the desire to reduce radiation exposure is greater.

Renal cysts rarely regress in size or disappear completely, often silently. Although this phenomenon may be caused by resorption of a hematoma misdiagnosed as a cyst, most cases are probably due to spontaneous cyst rupture. An increase in pressure within the cyst relative to the collecting system or the perinephric space may result in rupture. Such a pressure increase could be caused by hemorrhage into the cyst or by a change in the composition of the cystic fluid.

When clinically manifested, the most common manifestations of cyst rupture are hematuria and flank pain. The diagnosis can be made by excretory urography, CT, or retrograde pyelography if the cyst communicates with the collecting system. In most cases, the communication of the cyst with the collecting system closes spontaneously. Once the diagnosis is made, management is conservative.

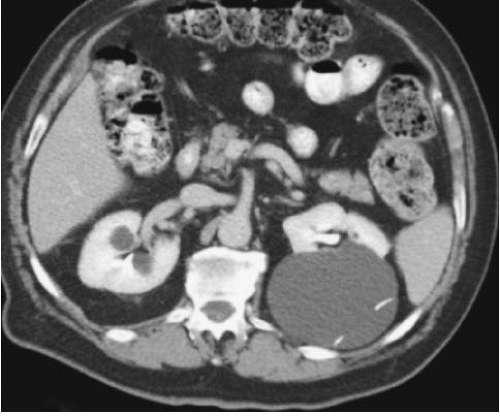

Unilateral Cystic Disease

Unilateral or localized renal cystic disease is characterized by replacement of all or a portion of one kidney by multiple cysts (Fig. 7.2) It is sometimes referred to as segmental cystic disease of the kidney. Although sometimes described as unilateral polycystic kidney disease, it is not familial. The disease is not progressive, and there is no association with renal failure or cysts in other organs. The pathogenesis is obscure, but it is hypothesized to be developmental in etiology. The most common clinical presentation is flank pain with or without hematuria.

Complicated Cysts

Cystic masses that do not satisfy the criteria of a benign simple cyst must be further evaluated to exclude malignancy. Various morphologic features are now recognized that exclude the diagnosis of a simple cyst.

Septations

Cysts may develop septations; their clinical significance depends on their thickness and number. When they are thin, smooth, do not have localized areas of thickening or irregularity and are few in number, the lesions are generally considered benign, complicated cysts. Occasionally, septations will be seen with US or MRI alone. Thin internal septations can be detected by ultrasound or MRI but their presence alone is not highly suggestive of malignancy. Many of these thin septations are not seen during excretory urography or CT, and they will likely be classified as benign simple cysts.

When a cystic mass contains one or more thick septations, a malignant lesion is possible. If there is associated nodularity, the lesion must be considered malignant.

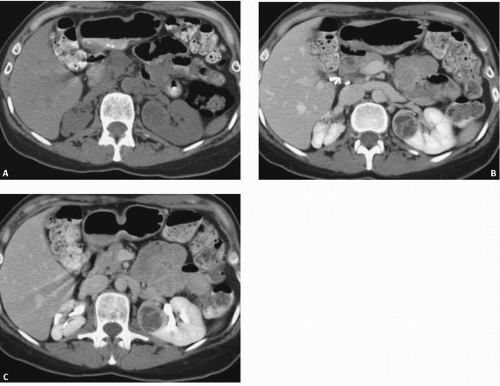

Calcification

The presence of calcification is also a nonspecific finding (Fig. 7.3). When evaluation of the kidney depended primarily on excretory urography, the presence of calcification, especially central calcification, was an ominous sign. However, CT has made the presence or absence of calcification almost irrelevant because wall thickening and soft-tissue masses can easily be detected without the help of calcification. Thin calcification in the wall or septum of a cyst is almost always benign and does not, in itself, warrant surgical exploration.

Thick Wall

A thick wall is incompatible with a simple cyst. It indicates that the lesion is another cystic mass or that the cyst has become complicated by some process such as infection, hemorrhage, or neoplasia. Inflammatory or infectious cystic masses may result in a thickened wall, typically associated with abundant perinephric stranding. A thick walled cystic renal mass may also be a cystic renal cell carcinoma (see Chapter 8). These lesions are generally considered indeterminate, and unless an inflammatory or infectious diagnosis can be made clinically or via percutaneous needle aspiration, close-interval follow-up or surgical exploration is indicated (Fig. 7.4). The presence of an associated soft-tissue tumor mass is an even more ominous finding and is highly suspicious for a malignancy.

Increased Density

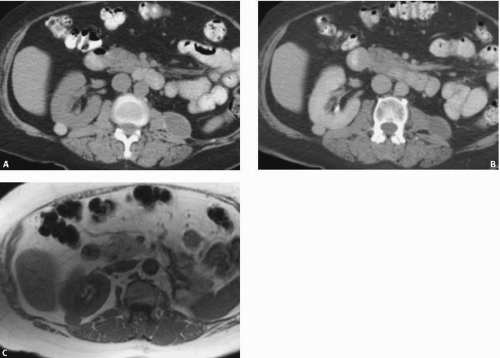

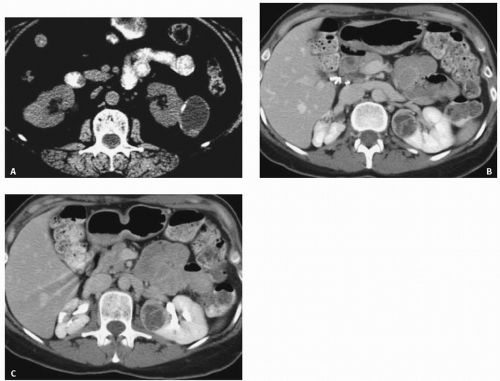

A cystic mass with a density above water must contain more than simple cystic fluid. A density greater than 20 HU is worrisome, but this reading should be checked against the water bath phantom, as there may be considerable drift in CT attenuation values. Many cystic renal masses with an attenuation slightly above 20 HU are proteinaceous cysts; however, attenuation values above water could also represent a solid neoplasm. If an increased attenuation is present, further evaluation with US, or if necessary either CT or MRI, both before and after intravenous contrast medium administration is warranted. One category of an atypical renal cyst that has an increased attenuation value is the hyperdense or hyperattenuating cyst. These lesions look like typical simple cysts on CT examination in that they are round, well-marginated, homogeneous masses that do not enhance with intravenous contrast material administration. In order to be considered hyperdense cysts, they need to be small, peripheral lesions, measuring 3 cm or less in diameter (Fig. 7.5A, B). However, instead of displaying an attenuation of water, they measure higher than 20 HU, typically 50 to 90 HU. Those that are denser than renal parenchyma are easily recognized on an unenhanced CT examination, but they may be masked by enhanced renal parenchyma, because their densities are similar. Thus, these lesions are probably more common than is appreciated, inasmuch as most abdominal CT scans are performed after intravenous contrast medium administration. Hyperdense masses that are intrarenal are more problematic; care must be used to differentiate such lesions from hyperdense solid tumors (Fig. 7.6). It has been reported by Jonisch et al. that almost all renal masses with a native (unenhanced) attenuation above 70 HU are benign, hyperdense cysts.

There are several possible etiologies for a hyperdense renal cyst. The most common etiologies are hemorrhage and a high-protein content of the cyst fluid. However, a diffuse pastelike calcified material has also been found. Most of these hyperdense cysts are benign, but they must be carefully examined for other atypical features. CT examination before and after intravenous contrast medium administration is often helpful. A cyst will not enhance, whereas a solid tumor will.

HYPERDENSE CYSTS ON CT

Round, well-marginated mass 3 cm or smaller

High density (>20 HU) on unenhanced scan (typically 50-90 HU)

Homogeneously hyperdense, even using a narrow window setting

No enhancement after contrast medium administration

US may be useful in the evaluation of a renal mass that has an attenuation higher than water on CT. It may enable the examiner to distinguish between a cystic lesion and a solid lesion. With ultrasound, blood elements can sometimes be seen floating within the cyst. However, if the lesion cannot be clearly evaluated with US, CT, MRI (both before and after contrast material), percutaneous biopsy or surgical exploration may still be needed.

Hyperdense cysts can also be evaluated with MRI. Simple cysts have low-signal intensity on T1-weighted images, whereas hyperdense cysts due to hemorrhage or high-protein content may have high-signal intensity on all pulse sequences. Because blood elements tend to settle out, the more intense signal of the paramagnetic methemoglobin can be seen in the dependent portion of the cyst on T1-weighted images. The relative intensity of the two cyst layers may reverse on T2-weighted sequences. With time, hemorrhagic or proteinaceous cysts show low to intermediate signal on T1-weighted images and have similar appearance on T2-weighted images (Fig. 7.5C). A renal cell carcinoma can often be distinguished by its heterogeneity, indistinct or irregular margins, lack of a fluid-hemoglobin level, or enhancement.

Enhancement

The presence or absence of enhancement on CT or MRI after contrast medium administration is the single most important criterion for distinguishing benign cystic renal masses from vascular solid lesions. Enhancement on MRI can be measured by determining the percentage change in signal intensity values of a renal mass after contrast material; a threshold of 15% can be used as reported by Ho et al. (2002). Subtraction MR imaging offers another method of determining whether enhancement is present in a cystic mass. With this method, unenhanced fat saturated T1-weighted images are

subtracted from T1-weighted gadolinium-enhanced images, and the corresponding images are displayed. Images must be obtained in the same phase of respiration to avoid misregistration artifacts. When there is no enhancement, the mass will display uniformly absent signal and appear black.

subtracted from T1-weighted gadolinium-enhanced images, and the corresponding images are displayed. Images must be obtained in the same phase of respiration to avoid misregistration artifacts. When there is no enhancement, the mass will display uniformly absent signal and appear black.

At CT, enhancement is determined by measuring the difference in attenuation of a mass or a region of a mass between the enhanced and unenhanced scans. If a region of a cystic mass enhances less than 10 HU, it is considered nonenhancing. If a region enhnances by 20 HU or more, it is considered enhancing. If the

difference is between 10 and 20, it is indeterminate and generally US or MRI is needed to determine if the region of the mass is solid. It is helpful to check potential enhancement against internal standards like bile in the gallbladder, urine in the bladder, or obvious renal cysts in order to determine whether true enhancement is present. With complex and heterogeneous lesions, multiple small attenuation measurements should be obtained while being certain that obvious sources of error like the renal sinus or perinephric fat are excluded from the measurement.

difference is between 10 and 20, it is indeterminate and generally US or MRI is needed to determine if the region of the mass is solid. It is helpful to check potential enhancement against internal standards like bile in the gallbladder, urine in the bladder, or obvious renal cysts in order to determine whether true enhancement is present. With complex and heterogeneous lesions, multiple small attenuation measurements should be obtained while being certain that obvious sources of error like the renal sinus or perinephric fat are excluded from the measurement.

The term pseudoenhancement has been used to describe the spurious increase in enhancement after contrast medium administration. It is caused by the reconstruction algorithm used by modern scanners that adjusts for beam-hardening effects. Pseudoenhancement is most pronounced with small (generally <1 cm), intrarenal lesions during the early phases of contrast enhancement when plasma contrast medium concentration is at its highest. When one is uncertain whether there is true enhancement or pseudoenhancement on CT, an alternate imaging modality such as US or MRI may be helpful. However, if it is a hemorrhagic cyst, the MR subtraction technique described earlier may be the best alternate study.

Bosniak Classification

To clarify the need for further evaluation or treatment of complicated cystic lesions, Bosniak has classified cystic renal masses into five categories.

Category I masses are cysts that fulfill all of the criteria for a benign, simple cyst. No further evaluation is needed.

Category II masses are those with some atypical features but are reliably considered benign. Such features include few, thin nonenhancing septa or thin, rimlike, border-forming calcification (Fig. 7.3). Exophytic (at least a quarter of its circumference abutting fat) hyperdense cysts that fulfill all of the criteria described above are included in this category (Fig. 7.5).

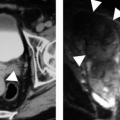

Catgeory IIF masses also include a subset of patients with findings that are a bit more worrisome. These lesions are considered Category IIF (“F” for follow-up). Such findings include more than a few thin septations with minimal, so-called perceived enhancement (because the septa are too small to place a region of interest on them), or minimal wall or septal thickening (Fig. 7.7). Intrarenal or large (>3 cm) masses that otherwise fulfill the crietria for a hyperdense cyst are placed in this category. Management recommendations include follow-up evaluation in 6 months and repeated at 1-year intervals to make sure the mass is not growing or, more importantly, not developing worrisome morphologic features.

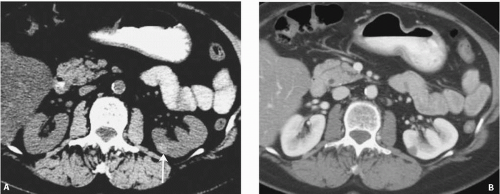

Category III lesions cannot be distinguished from malignancies; they generally require surgical exploration. The overall risk of malignancy is probably greater than 50%. Features of masses in category III include one or more thick or irregular septations, some thickened walls, or large, nonborderforming calcifications (Figs. 7.3 and 7.8). There may be measurable enhancement present. Although some will be benign, these masses generally should be removed because no additional imaging can unequivocally prove that they are benign. Lesions in this category are often

mimicked by hemorrhagic, inflammatory, or infected cysts. As a result, it is important to always consider nonneoplastic etiologies of a renal mass-like lesion before applying the Bosniak classification, particularly infections such as focal bacterial pyelonephritis and abscesses. If a diagnosis of an infectious etiology cannot be made on the basis of imaging findings and clinical presentation alone, percutaneous needle aspiration biopsy should be considered. Although the remainder are generally considered surgical lesions, some have advocated the use of percutaneous biopsy in patients who are too ill for surgery. However, the solid portions of these masses are difficult to sample and unless a confident specific benign entity can be diagnosed by biopsy, negative results should be viewed with extreme caution.

FIGURE 7.8. Bosniak III cyst. Excretory phase image shows a cystic left renal mass with enhancing septa. Proven renal cell carcinoma.

Although the Bosniak system has received criticism because of the subjective nature of the assignment of a particular lesion to each category, most authorities still find the system to be a useful method by which the level of concern about a particular lesion can be expressed. Category I and IV lesions can generally be assigned with a high level of agreement among observers. The difficulty is in the assignment of lesions in categories II, IIF, and III and the markedly different management this assignment entails. In addition, other factors such as the patient’s age and coexisting morbidity also play a major role in how a lesion is managed. For example, a small cystic mass with a solid component may be followed in a patient

with limited life expectancy or severe comorbidities, whereas it would be removed in the general population with similar imaging findings.

with limited life expectancy or severe comorbidities, whereas it would be removed in the general population with similar imaging findings.

BOSNIAK CLASSIFICATION

Category I—uncomplicated simple cyst with no atypical features

Category II—minimally atypical features with little, if any, risk of malignancy

Category IIF—minimally concerning features requiring follow-up

Category III—Indeterminate lesion with a significant concern for malignancy

Category IV—Cystic appearing but frankly malignant features

Milk of Calcium Cyst

Milk of calcium is a collection of small calcific granules in the cystic fluid. The granules, usually calcium carbonate, are in suspension and layer out in the dependent portion of the cyst. They are seen most frequently in calyceal diverticula (see Chapter 15). Milk of calcium cysts have no sex predilection but are more common in the upper poles of the kidneys.

The milk of calcium nature of these calculi may not be appreciated on a supine radiograph, but the fluid-calcium layer is easily detected on upright films or CT examination. A horizontal line of calcium density can also be detected using ultrasound, regardless of the patient’s position. Most of these cysts are detected as incidental findings, and intervention is unnecessary.

▪ MEDULLARY CYSTIC DISEASE

This disease complex includes medullary cystic disease and juvenile nephronophthisis. Extrarenal manifestations such as retinal degeneration, hepatic fibrosis, and skeletal abnormalities are associated with the juvenile form. The kidneys are small to normal in size and maintain a normal configuration and smooth contour. A variable number of small cysts, up to 2 cm in diameter, are located primarily in the medulla. The cortex is thin but does not contain cysts. Biopsy shows interstitial and periglomerular fibrosis as well as tubular atrophy. However, the diagnosis cannot be made if cysts are not included in the biopsy specimen, because the fibrotic changes are nonspecific.

The uremic medullary cystic diseases can be classified by the age of onset. The adult form is transmitted by autosomal-dominant inheritance. Patients usually present as young adults with anemia, which may be severe, and have progressive renal failure. These patients have a saltwasting nephropathy that is not corrected with mineralocorticoids.

Other than a fixed low-specific gravity, the urine sediment is normal. Hypertension may develop near the end of the disease course.

Other than a fixed low-specific gravity, the urine sediment is normal. Hypertension may develop near the end of the disease course.

Patients with juvenile nephronophthisis typically present at 3 to 5 years of age with polydipsia and polyuria. The clinical course with anemia and progressive renal failure is similar to the adultonset variety, but progression is slower, with 8 to 10 years before terminal uremia. Juvenile nephronophthisis is transmitted by autosomal-recessive inheritance.

Abdominal radiographs may demonstrate small kidneys without calcification. High-dose nephrotomography, CT, or MRI reveals a thin renal cortex. Linear contrast collections radiating from the renal pyramids may be seen. However, contrast-medium enhanced examinations such as excretory urography and enhanced CT scans are not likely to be helpful and are seldom performed because of renal failure. Unenhanced CT or MRI demonstrates small smooth kidneys and may reveal the small medullary cysts.

High-resolution ultrasound may be the examination of choice in these patients. The corticomedullary differentiation is lost, and the parenchyma appears isoechoic or hypoechoic with the liver or spleen. In patients with severe uremia, medullary cysts can usually be demonstrated, but they may not be detectable in milder cases. Examination with unenhanced MRI may be particularly useful when ultrasound is indeterminate. The problems with motion artifact due to breathing are decreased with fast spin echo breath-hold techniques.

▪ POLYCYSTIC RENAL DISEASE

Autosomal Recessive Polycystic Disease

Infantile polycystic disease (IPCD) is transmitted by autosomal-recessive inheritance and is frequently referred to as autosomal-recessive polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD). It includes a spectrum of abnormalities ranging from newborns with grossly enlarged sponge kidneys to older children with medullary ductal ectasia. The older children also develop hepatic fibrosis that progresses to portal hypertension and esophageal varices.

Congenital hepatic fibrosis (CHF) may represent yet another disease transmitted by autosomal-recessive inheritance in which the renal disease is different from and milder than IPCD. Other entities associated with CHF include adult polycystic disease (APCD), multicystic dysplastic kidneys (MCDK), choledochal cyst, and Caroli disease. However, medullary ductal ectasia is found in all forms of IPCD, with or without CHF.

Patients with severe forms of IPCD have renal failure at birth and most die within the first few days of life. Patients with the less severe disease have a milder renal disease characterized by tubular ectasia and renal cysts. They often present with symptoms arising from hepatic fibrosis with portal hypertension and varices rather than from renal failure. There seems to be an inverse relationship between the renal and the hepatic manifestations of the disease; when the renal disease is present at birth, the hepatic manifestations are mild. When the disease presents in older children, the hepatic component dominates; whereas the renal manifestations are less severe. It appears as a single gene located on chromosome 6 for all forms of the disease.

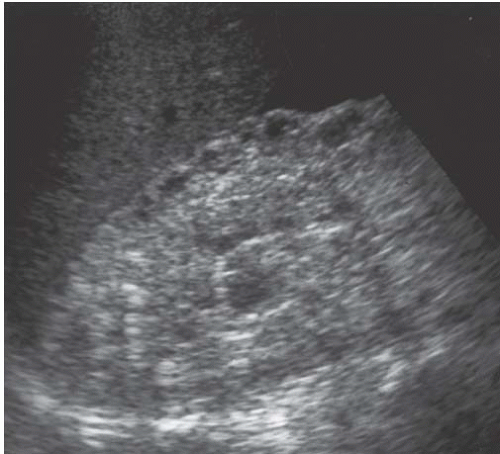

The radiographic manifestations reflect the age of onset and the severity of renal involvement. In the neonatal form, there is a massive enlargement of the kidneys that maintain their reniform shape. The kidneys are enlarged but function poorly. The nephrogram is faint with blotchy opacification. Linear striations due to stasis of contrast medium in the dilated renal tubules have been described. The numerous small (1 to 2 mm) cysts in both the cortex and medulla result in increased echogenicity on sonography. However, with high-resolution scanners a peripheral sonolucent rim can be seen representing compressed renal cortex (Fig. 7.11). A prominent renal pelvis and calyces may result in a sonolucent central zone.

FIGURE 7.11. Autosomal recessive polycystic disease. The kidney is enlarged. Numerous small cysts create disorganized echogenicity and loss of corticomedullary differentiation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|