Retroperitoneal Hemorrhage

Mandeep Dagli

Retroperitoneal hemorrhage is most commonly seen following blunt or penetrating trauma (often in association with pelvic fracture), but it can also occur with anticoagulation medication, ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, renal tumors, or bleeding diathesis. Rarely, it may be spontaneous. It is associated with a high mortality rate when due to trauma.

Anatomy of the Retroperitoneum

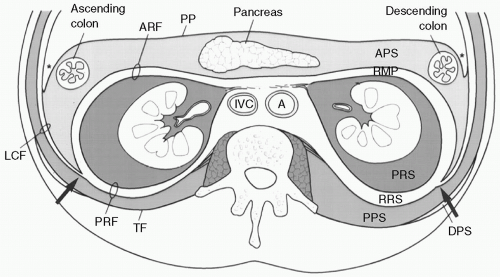

An understanding of basic retroperitoneal anatomy is essential to both the interpretation of imaging findings and management of retroperitoneal hemorrhage. The retroperitoneum consists of three main compartments: the anterior pararenal space, the perirenal space (PRS), and the posterior pararenal space which are defined by three fascial planes: the anterior renal fascia, the posterior renal fascia, and the lateroconal fascia, respectively.

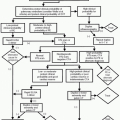

In general, hemorrhage will be confined to the compartment of origin, thereby limiting the differential diagnosis (Fig. 37-1).

Anterior pararenal space: ascending and descending colon, pancreas, second and third portions of the duodenum.

Perirenal space (PRS): kidney, adrenal gland, proximal ureter, renal vessels and lymphatics.

Posterior pararenal space: mainly fat.

In cases of substantial hemorrhage, blood can spread between compartments through perinephric bridging septa. Superiorly, the PRS is open to the bare area of the liver. Inferiorly, the PRSs communicate at the level of lower lumbar spine. The blood can also extend across the midline through thin communication that is present anterior to aorta and inferior vena cava (IVC) at the level of lower lumbar spine.

Symptoms and Signs

History of trauma (especially pelvic fracture), back/flank pain, falling hematocrit, hypotension (the retroperitoneum can hold up to 4 L of blood), hematuria, Grey-Turner sign (bluish discoloration of flanks).

Etiology

Iatrogenic anticoagulation, catheterization, recent percutaneous abdominal intervention.

Arterial: aneurysms.

Neoplasm: renal cell carcinoma, renal adrenal myelolipoma (AML), adrenal carcinoma, and AML

Trauma: penetrating and blunt trauma which can result in organ, bony, or vascular injury. Life-threatening hemorrhage in pelvic fractures may be secondary to fractured bone, venous plexus, major pelvic veins, or iliac arterial branches.

Inflammation: pancreatitis or infection leading to vascular injury.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|