Jordan C. Tasse • Bulent Arslan • Ulku Cenk Turba

Sclerosing agents represent another category of liquid embolic agents. They act by damaging endothelial cells, leading to an inflammatory fibrosis and irreversible vascular thrombosis. The sclerosant effect typically depends on the strength of the particular agent being used and the amount of time that it is in contact with the endothelial lining of the vessel.

ABSOLUTE ALCOHOL (ETHANOL)

Alcohol is one of the most potent of the liquid embolic agents. It can be injected using a catheter-based intravascular approach or using a direct percutaneous approach. Absolute alcohol is an effective permanent embolization agent that has been used in various scenarios. Some of the applications of absolute alcohol include percutaneous tumor ablation/treatment, presurgical embolization of renal cell carcinoma, and treatment of vascular malformations. Direct alcohol injection has been used for treatment of small (<2 cm) hepatocellular carcinomas and for sclerotherapy of painful abdominal cysts and postsurgical seromas.

Alcohol acts by denaturing endothelial proteins, leading to activation of the coagulation cascade inducing subsequent thrombosis.1 Ethanol also induces vasospasm. Occlusion is typically seen within seconds after injection and progresses for several days. The effect depends on ethanol concentration, time of exposure, and injection rate; rapid injection rates produce more endothelial damage and parenchymal necrosis with less thrombosis, whereas slower injection rates produce more thrombosis but less endothelial damage and necrosis.2 The use of alcohol as an embolic agent is not without risk. The disadvantages of alcohol include the risk of damage to surrounding tissues including nerves, skin, and mucosa due to its penetrative properties. Patients may experience severe procedural pain. Monitoring for systemic toxicity is also crucial when the dose of alcohol is greater than 1 mL/kg or if the total volume exceeds 60 mL. The side effects may include central nervous system depression, hemolysis, and cardiac arrest.

Given these possible effects, it is important to minimize the incidence of nontarget embolization. The techniques used to reduce this risk include slow injection, use of balloon occlusion of the arterial inflow, or balloon occlusion of the draining vein.

ETHANOLAMINE OLEATE

Ethamolin (QOL Medical, LLC, Kirkland, Washington)

Ethanolamine oleate is a salt of a fatty acid with excellent thrombogenic properties. It is typically injected as a mixture consisting of 5% ethanolamine oleate and nonionic contrast material or iodized oil (5:1 ratio) for radiopacity. It combines its inherent thrombogenic properties with an inflammatory response to oleic acid that occurs in the vascular wall. When compared to ethanol, ethanolamine oleate has a less penetrating effect in comparison and is therefore considered safer to use in vascular structures with close proximity to nerves, skin, and mucosa.

Ethanolamine oleate has most commonly been used for sclerosis of gastroesophageal varices, venous malformations, and sclerotherapy of cyst, seromas, etc. Some risks associated with ethanolamine oleate include renal failure, pulmonary edema, and anaphylaxis. Although it is considered experimental, haptoglobin can be administered with ethanolamine oleate to bind free hemoglobin and albumin before injection to prevent hemolysis-induced renal insufficiency.3

SODIUM TETRADECYL SULFATE

Sotradecol (AngioDynamics, Queesnbury, New York), FibroVein (STD Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Hereford, United Kingdom), Trombovar (Aventis Pharma, Le Trait, France), Tromboject (Omega Laboratories Ltd., Montreal, Quebec, Canada)

Sodium tetradecyl sulfate (STS; Sotradecol) is a long-chain fatty acid salt with detergent properties. It is an effective sclerosing agent that acts by inducing endothelial damage and dissolution of the endothelial cell membrane, which causes cell overhydration. Sotradecol is U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for distribution in 1% and 3% concentrations. It is typically mixed with a water-soluble contrast agent to provide radiopacity. It can also be mixed with iodized poppy seed oil (i.e., Lipiodol) with air or carbon dioxide to create a foam.4 Foamed detergent sclerosants have been reported to be more potent than their liquid counterpart.5

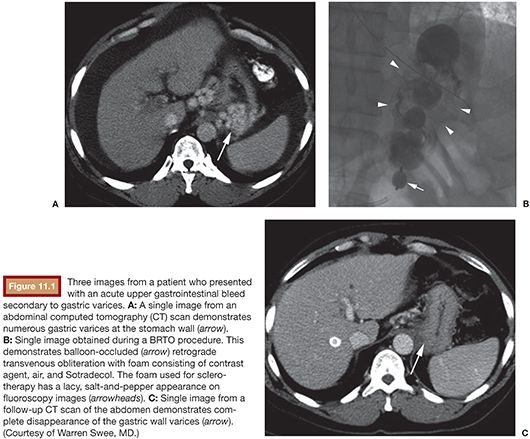

Sotradecol has been in use for more than 50 years and can be injected via an intravascular route or a direct percutaneous approach. Typical uses include the direct injection of varicose veins (0.1% to 3% concentration), sclerosis of gonadal veins in the management of varicoceles and pelvic congestion syndrome (1% to 3% concentration), sclerotherapy of peripheral venous malformation (1% to 3% concentration), as well as balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) procedures for bleeding gastric varices treatment (Fig. 11.1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree