Chang Jin Yoon • Jae Hyung Park

Transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) has been commonly used in treatment of malignant liver tumors. Although rare, however, it can be indicated in various benign liver diseases including benign liver tumors, iatrogenic vascular injury, polycystic liver disease, and congenital vascular lesions.

Owing to the widespread use of imaging analyses, either routinely or to evaluate symptomatic patients, benign liver tumors are diagnosed with increasing frequency.1 Most benign liver tumors are incidentally discovered in otherwise healthy individuals. However, some of them are associated with serious complications, which require prompt treatments. Surgical resection has been considered a standard treatment for large or symptomatic lesions. TAE has been used as an alternative treatment for patients who cannot undergo surgery due to poor clinical conditions. It is also indicated to achieve hemostasis in cases of tumor rupture or as a preoperative procedure before surgical resection.2–6

TAE also plays an essential role in treatment of focal vascular abnormality of the liver. They are most commonly caused by iatrogenic injury following radiologic or surgical liver interventions.7–9 Recently, as percutaneous transhepatic procedures are more frequently carried out, such vascular lesions are becoming more prevalent. Common vascular lesions include arterial pseudoaneurysm, arterioportal fistula, and arteriobiliary fistula. Small lesions are asymptomatic and may not need any specific treatment. However, a large aneurysm or fistulas with large amount of blood flows can lead to hemobilia, gastrointestinal bleeding, and portal hypertension. Congenital portosystemic shunt or vascular malformations are rare but can be associated with serious and potentially fatal complications.10 In the past, most symptomatic vascular lesions required surgical treatment, but TAE has currently emerged as a valuable minimally invasive treatment option.11

TECHNIQUES AND EMBOLIC MATERIALS

Angiographic access is gained on either a femoral or a left axillary artery using Seldinger technique. Visceral arteriography is performed using a preshaped 4-Fr or 5-Fr angiographic catheter. In the liver, arterial anatomic variations are common. Selective examination of the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries is often necessary. Common variants include the left hepatic artery arising from the left gastric artery and the right hepatic artery replaced to the superior mesenteric artery. It is important to scrutinize the arteriogram for defects in hepatic parenchymal enhancement, which might alert one to the presence of anatomic variants or accessory vessels. Two or more projection hepatic angiograms including the portal venous phase may be required to identify the location of lesion and feeding vessels identified. The vessels to be embolized are catheterized as selectively as possible with use of a 2-Fr or 3-Fr microcatheter.

The liver is well suited to TAE because of its dual blood supply. Arterial embolization is unlikely to result in tissue infarction unless there is concomitant injury to the portal venous system. To minimize normal hepatic parenchyma, it is preferable to place the embolic agent as close to the target lesions as possible. The major considerations for selecting an embolic agent are lesion type and location, individual vascular anatomy, reliability of delivery, and preservation of normal tissue. For benign liver tumors, particulate embolic agents such as polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and gelatin sponge particles have been frequently employed.12 However, PVA particles are known to clump, resulting in more proximal vessel occlusion. Recently, calibrated microspheres (trisacryl gelatin microspheres) are used to achieve distal vessel blockade, leading to ischemic tumor necrosis.13 For embolization of hepatic vascular injury such as arterioportal/arteriobiliary fistulas and pseudoaneurysms, microcoils, gelatin sponge pledgets, and N-butyl cyanoacylate (NBCA) are typically used either alone or in combination.7–9 Coils are ideal for precise single-vessel occlusion. They provide controlled delivery with rapid occlusion and are available in various sizes. When using coils, they should be tightly packed without interstices to avoid late recanalization and coil migration. When treating arterial pseudoaneurysm, coils should not be placed inside the aneurysmal sac because there is risk of late rupture. The proximal and distal vessels to the pseudoaneurysm should be embolized so that revascularization by backflow may not occur (sandwich technique). Recently, NBCA has been gaining interest as a useful embolic material for TAE. It occludes target vessels rapidly and completely, which results in more reliable embolization and may reduce fluoroscopic and procedure time. By adjusting the ratio of NBCA and iodized oil, polymerization time and, accordingly, the level of embolization within target vessels can be controlled. This unique character of NBCA is especially useful when a microcatheter is not able to be advanced to desirable intravascular position due to tortuous vascular anatomy or arterial stenosis. In spite of these advantages, the use of liquid embolic agents including NBCA has been limited in TAE because of the concern that they carry a high risk for severe complications such as tissue necrosis and nontarget embolization secondary to uncontrolled reflux.14 In embolization of a large, high-flow arteriovenous shunt, a more durable embolic device with large diameter such as Amplatzer Vascular Plug (St. Jude Medical, Inc., St. Paul, Minnesota) may be required to prevent migration.

CLINICAL APPLICATIONS

Benign Liver Tumors

Hepatocellular Adenoma

Hepatocellular adenoma (HA) is a rare hepatic tumor that is strongly associated with use of oral contraceptives or anabolic steroids and glycogen storage disease.15 Unlike other benign liver tumors, approximately 80% of patients with HA have clinical symptoms; of these, half present with acute-onset abdominal pain due to hemorrhage and half present with symptoms related to mass effect. Only 20% of HAs are found as incidental findings.16 Malignant transformation of HA is rare and associated with β-catenin mutations that are also found in hepatocellular carcinoma.17 There are controversies with regard to the optimal treatment for HA because the potential for hemorrhage or malignant transformation of tumor is difficult to estimate. The patients with lesions smaller than 5 cm and normal α-fetoprotein levels are typically treated conservatively. Discontinuation of oral contraceptives may lead to regression of the tumor.18 Patients with lesions larger than 5 cm should be considered for surgical resection because lesion size is an important indicator of potentials for hemorrhage or progression to hepatocellular carcinoma.19 However, surgery carries an increased risk of postoperative morbidity and a longer recovery time and may not be practical in patients with multiple bilateral HAs.20

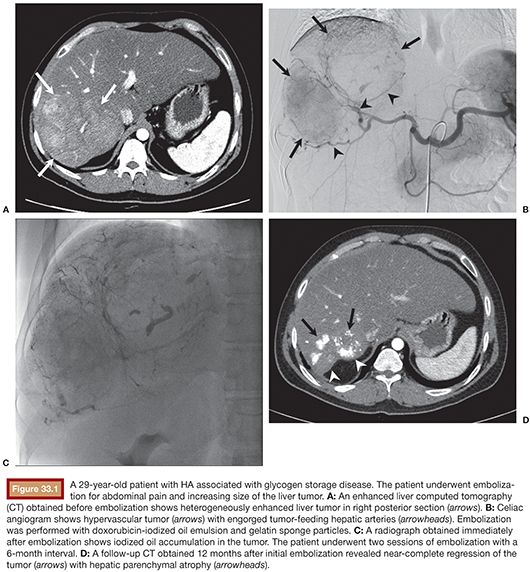

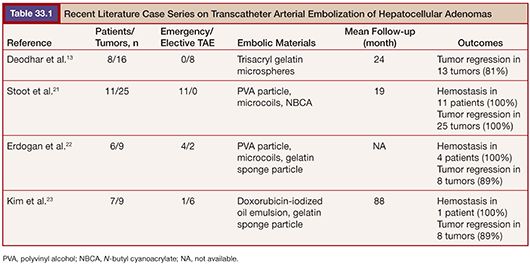

TAE, on the contrary, is minimally invasive. It can be applied to multiple and bilateral tumors. It can safely be repeated and is effective in decreasing the lesion size (Fig. 33.1). The data from literatures on embolization of HAs are summarized in Table 33.1. Currently, TAE is commonly indicated in patients presenting with acute hemorrhage from HAs. In several studies, TAE has been successfully performed to obtain adequate hemostasis without the need for urgent laparotomy.5,21,22 Stoot et al.21 treated 11 patients with ruptured HAs. Ten of the patients were stabilized after a single TAE, whereas one other patient needed three TAE sessions. No emergency resections were needed and only minor complications were found. In all patients, tumor size decreased after follow-up, with secondary resection being indicated only in a minority of patients. Because an emergency surgical resection inevitably involves considerable morbidity and mortality, TAE is proposed as the first treatment in hemodynamically unstable patients with ruptured HAs. In addition to the emergency indication, several reports have focused on the elective use of TAE for HAs larger than 5 cm with the aim of reducing the tumor mass by complete cessation of the arterial blood flow.13,23,24 Kim et al.23 performed TAE in 7 patients with large HAs and achieved tumor regression more than 50% in 6 patients. Complete resolution of the tumor was seen in 2 patients. No serious complication was reported except self-limiting postembolization syndrome. In past several years, TAE has been increasingly used in patients with unruptured HAs.25 A randomized controlled study comparing surgical resection versus selective TAE is now going on.26

Focal Nodular Hyperplasia

Focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) is the second most common benign liver tumor next to hemangioma and usually affects women of childbearing or middle age.27 It is more often a solitary subcapsular lesion measuring less than 5 cm in size. Histologically, FNH is composed primarily of Kupffer cells and hepatocytes. It is believed to result from the response to a preexisting vascular abnormality. Patients with FNH are typically asymptomatic and may be managed conservatively because there is no predisposition to hemorrhage or malignant transformation. However, up to 30% of patients present with a vague abdominal pain due to mass effect, hepatomegaly, and/or abdominal mass.28 Treatment should be considered in cases with a progressive increase in size or compressive symptoms. Surgical resection is currently the treatment of choice for FNH when indicated. TAE is considered to be an alternative to surgery when there is considerable surgical risk because of localization or poor clinical condition. Given FNH’s genesis in abnormal arterial flow, embolization is a feasible strategy.29 Angiographic findings are fairly characteristic. Hepatic angiogram shows a hypervascular mass with dense tumor blush in the capillary and portal venous phases. Lucent septations can be seen within the blush corresponding with the fibrous septations. A single central feeding artery penetrating the tumor mass is usually seen in a large FNH, which makes TAE more feasible. When the lesion is supplied by multiple small feeding vessels, the need for repeat TAE should be anticipated.29 Several small case series reported successful application of TAE in patients with symptomatic FNHs. Microspheres 150 to 750 µm were the most commonly employed embolic agent. TAE relieved symptoms in most patients and led to substantial shrinkage of the tumors (20% to 90%).12,29,30

Cavernous Hemangioma

Cavernous hemangioma is the most common benign tumor affecting the liver, with an estimated prevalence of 3% to 20%.27 It occurs in all age groups but is more frequently discovered between the third and fifth decade, with a mean age of 50 years at diagnosis and is seen more often in females (female-to-male ratio 6:1).27 Most hemangiomas are small, asymptomatic, and usually require no treatment or follow-up. However, giant hemangiomas (diameter >4 cm) may present with abdominal pain or discomfort (23% to 57%) caused by displacement of other organs, capsular stretch, partial infarction, or intralesional hemorrhage. A spontaneous or traumatic rupture is rare (1% to 4%), but mortality in this patient group is high (36% to 39%).3 Kasabach-Merritt syndrome is also a rare but well-known complication of giant hemangiomas. It is characterized by the combination of a vascular tumor and consumptive coagulopathy, which can progress to disseminated coagulopathy. There is no consensus regarding the optimal management of giant hemangiomas, but presence of established complications, diagnostic uncertainty, and incapacitating symptoms are generally considered indications for surgical enucleation or resection.

TAE has been suggested as a good alternative treatment of symptomatic hemangiomas, either alone or as a preoperative procedure before surgical resection.31–34 TAE can be successfully applied in tumors with extensive hilar involvement that makes surgical procedures difficult,34 in patients with ruptured hemangiomas,33 or to reduce blood loss at the time of surgery.31 TAE rapidly and safely corrects the coagulopathy caused by Kasabach-Merritt syndrome, which is essential because these patients are poor surgical candidates.35 Various embolic materials are being used, such as gelatin particle, steel coils, PVA particles, and NBCA. Typically, vascular interstices within the lesion are first embolized with PVA particles, followed by embolization of the principal arteries with steel coils.36 In a multicenter study from China, hepatic hemangiomas of 98 patients were treated with chemoembolization using pingyangmycin-Lipiodol emulsion. Pingyangmycin has been found, like bleomycin, to reduce the DNA synthesis of cancer cells and cut off the DNA chain. The presumable mechanism of this treatment relies on pingyangmycin’s ability to destroy the endothelial cells, resulting in the formation of microthrombi in sinuses and causing atrophy and fibrosis of the tumor. The tumor diameters decreased significantly from 9.7 to 3.0 cm at 12 months follow-up. Clinical symptoms were relieved in all patients. The most severe potential complication caused by pingyangmycin is pulmonary fibrosis. However, no pulmonary fibrosis has been observed in used dosage (8 to 24 mg).

Iatrogenic Vascular Injury

Iatogenic hepatic vascular injury is by far most commonly caused by radiologic transhepatic procedures including percutaneous liver biopsy, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD), transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), and radiofrequency ablation (RFA).37 The incidence of clinically significant vascular injury following RFA and liver biopsy is estimated to be 0% to 0.5% and 0.06% to 1%, respectively. PTBD carries a higher risk (2% to 10%) because of the use of larger catheters and the presence of bile stasis.38–40 Most common clinical presentation is gastrointestinal bleeding due to hemobilia.41 This is due to close proximity of the hepatic arteriole and portal venule along with the biliary radical in the portal triad. Thus, an injury to the artery and vein makes the adjacent biliary duct prone to injury. In up to 90% of the patients with iatrogenic hemobilia, a vascular abnormality is found on angiography.41 The most common finding is a pseudoaneurysm, followed by an arteriobiliary or an arterioportal fistula. Some arterioportal fistulas may remain quiescent for long periods, up to many years, but a large arterioportal fistula can lead to dynamic portal hypertension with gastroesophageal varices, ascites, or mesenteric ischemia.42

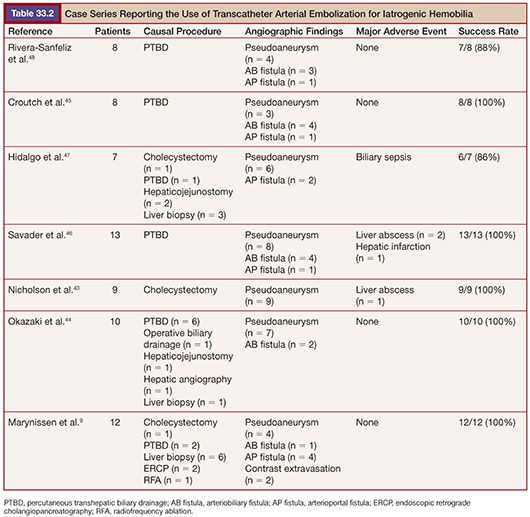

Nowadays, TAE is the preferred method to treat intrahepatic iatrogenic vascular injuries, which gives satisfactory results; success rates of 80% to 100% have been reported in the literature.9,43–48 An overview of the embolization results for iatrogenic hepatic vascular injuries in the literature is presented in Table 33.2. Surgery is usually employed secondarily for unsuccessful embolization and complex lesions. The aim of embolization is to achieve selective and complete thrombosis of pseudoaneurysm or fistula closure with preservation of the adjacent normal vasculature. To achieve this, a microcatheter should be positioned as close as possible to the lesion site to limit hepatic devascularization. For hepatic arterial pseudoaneurysm, microcoils are most commonly used to embolize hepatic arteries just distal and proximal to the lesion, which allows for thrombosis (Fig. 33.2). When embolizing the right or left hepatic arteries, contralateral peripheral vascular bed is filled through intrahepatic collateral vessels immediately; thus, hepatic infarction is unlikely to occur. For embolization of arterioportal fistulas, the embolic agents should be chosen according to the size of the vascular communication. For high-flow fistulas, microcoils are most commonly selected embolic agent.8,9,49 However, the use of microcoils has a potential risk of migration of the coil into the portal vein, especially when fistula is larger than 8 mm.37 Detachable coils, such as the interlocking detachable coil or Guglielmi detachable coil, can avoid the risk of coil migration, but they may not cause thrombosis in high-flow fistula. Hirakawa et al.8 suggested the use of detachable coil as a first anchoring coil and subsequent fibered coils to avoid coil migration and to achieve complete occlusion of large, high-flow fistula. Liquid embolic agent such as NBCA has not been widely used due to its higher risk of migration into the portal venous system. However, it can be a useful embolic agent when there is the presence of multiple small fistulae, all of which had to be embolized,7 or proper placement of a microcatheter at the desirable intra-arterial position is impossible.8 Particles such as gelatin sponge or PVA can be used in small, slow-flow fistulas.11

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree