Jean Noel Buy1 and Michel Ghossain2

(1)

Service Radiologie, Hopital Hotel-Dieu, Paris, France

(2)

Department of Radiology, Hotel Dieu de France, Beirut, Lebanon

17.1 Endometriosis

17.1.1 Microscopic Definition

17.1.2 Introduction

17.1.3 Pathology

17.1.4 Etiology and Pathogenesis

17.1.5 Distribution

17.1.6 Classification

17.1.7 Clinical Findings

17.1.8 Laboratory Tests

17.1.9 Laparoscopy

17.1.10 Imaging Modalities

17.2 Endosalpingiosis

17.2.1 Microscopic Definition []

17.2.2 Locations

17.2.3 Aspect

17.2.4 Association

17.2.5 Imaging Findings

17.3 Endocervicosis

17.3.1 Microscopic Definition

17.3.2 Location

17.3.3 Aspect

17.3.4 Clinical Findings

17.3.5 Imaging Findings []

17.5 Leiomyomatosis

Abstract

Anatomical definition: The secondary mullerian system is the pelvic and lower abdominal mesothelium and the subjacent mesenchyma [1, 2]. The mullerian potential of this layer is consistent with its close embryonic relation to the mullerian ducts that arise by invagination of the coelomic epithelium

Anatomical definition: The secondary mullerian system is the pelvic and lower abdominal mesothelium and the subjacent mesenchyma [1, 2]. The mullerian potential of this layer is consistent with its close embryonic relation to the mullerian ducts that arise by invagination of the coelomic epithelium.

Pathological definition: The peritoneal lesions of the secondary mullerian system are characterized by:

1.

Epithelial differentiation in serous, endometrioid, and mucinous epithelium, simulating normal or neoplastic tubal, endometrial, endocervical epithelium; (rarely differentiation in urothelial epithelium exemplified by Walthard nests).

2.

Proliferation of the subjacent mesenchyme may accompany epithelial differentiation in endometrial stromal-type cells, decidua, or smooth muscle.

Lesions

17.1 Endometriosis

17.1.1 Microscopic Definition

Presence of endometrial epithelium and stroma in an ectopic site excluding the myometrium. Usually both epithelium and stroma are seen, but occasionally, the diagnosis can be made when only one component is present [3].

17.1.2 Introduction

1.

Pelvic endometriosis is a common disease associated with a variety of symptoms principally pain and infertility. It is estimated to occur in 10 % of women of reproductive age [4]. This prevalence may be as high as 24.5 and 19.6 %, respectively, in patients undergoing laparoscopy for pelvic pain and infertility [5].

2.

3.

Although classically this disease uses to have mainly gynecologic sites of implantations mainly ovaries, tubes, and peritoneum covering these organs, presentations have significantly changed these past years with tremendous increase in subperitoneal locations particularly GI tract locations mainly the rectum and sigmoid, so that this disease leads the patient to consult not only the gynecologist but also the gastroenterologist.

17.1.3 Pathology

17.1.3.1 Microscopic Findings

Typical

In reproductive-age woman, the typical appearance is one or more glands lined by endometrial epithelium, surrounded by a mantle of dense packed small fusiform cells with scanty cytoplasm and bland cytology, typical of nonneoplastic endometrial stromal cells.

Small blood vessels may be engorged. When seen in the ovary, endometriosis varies from microscopically dilated glands to grossly recognizable cysts, while in extra-ovarian sites cysts are less common to rare.

Unusual

1.

Metaplastic glandular changes: These changes include ciliated, eosinophilic, hobnail, and rarely squamous and mucinous metaplasia (see Chap. 22.3.3).

2.

Hyperplastic glandular changes: Hyperplastic changes similar to those occurring in the endometrium have been described in endometrial glands, sometimes related to an endogenous or exogenous estrogenic stimulus, or tamoxifen therapy. Hyperplastic changes are particularly common in cases of polypoid endometriosis. Such atypical changes have a malignant potential.

3.

Stromal changes: The endometriotic stroma may undergo metaplasia, typically smooth muscle metaplasia, which is most often encountered in the wall of ovarian endometriotic cysts but occasionally elsewhere. Extensive amounts of smooth muscle within the endometriotic stroma can result in endomyometriosis.

17.1.3.2 The Appearance of Endometriotic Tissue Varies with Hormonal Changes and with the Location of the Disease

With Hormonal Changes

In reproductive age woman:

In approximately 80 % of patients, the endometriotic lesions show cyclic changes although considerable variability in glandular and epithelial cell morphology may be observed [10, 11].

Periodic menstrual changes within the endometriotic focus will result in histologic evidence of recent and remote hemorrhage within the endometriotic stroma and glandular lumens and a secondary inflammatory response consisting predominantly of a diffuse infiltration of histiocytes [3]. The histiocytes convert the extravasated red blood cells into glycolipid and granular brown pigment, becoming so-called pseudoxanthoma cells, that can replace most or all the endometriotic stroma. Most of the pigment is hemofuscin and hemosiderin is typically present to a much lesser extent. The amount of pigment in an endometriotic lesion appears to increase with its age, and early lesions are frequently nonpigmented [12]. Variable numbers of lymphocytes and smaller numbers of other inflammatory cells may be present. Large numbers of neutrophils with microabscess formation should raise the possibility of secondary bacterial infection.

During pregnancy or progestin therapy:

1.

The endometriosis glands become atrophic, which are small and lined by cuboidal or flattened epithelial cells.

2.

The stroma exhibits marked decidual transformation (see Chap. 21.3.2).

In postmenopausal women:

The aspect is similar to a simple or cystic atrophy of the endometrium.

1.

The endometriotic glands become atrophic, which occasionally are cystic lined by flattened epithelial cells.

2.

The stroma is dense fibrotic with sometimes a barely perceptible tendency for the stroma to be more cellular close to the gland.

With the Location of the Disease

1.

In the ovary, the predominant pattern is a small hemorrhagic focus or a larger cyst containing menstrual debris and lined by endometrial epithelium associated by endometrial stroma. However, the epithelial and stromal lining of an endometriotic cyst frequently becomes attenuated and difficult to recognize. Commonly, this cyst lining is totally lost and is replaced by granulation tissue, dense fibrous tissue, and numerous pigmented macrophages. In this case, a definitive diagnosis of endometriosis cannot be made because a similar appearance can be seen in an old corpus luteum cyst [3].

2.

In the peritoneum, the endometrial lesions are constituted by implants and adhesions secondary to the inflammatory process. Implants can have different patterns and are classically divided in red, black, and white lesions [13].

3.

When endometriotic lesions are located in tissues containing smooth muscle such as the uterine ligaments or the muscular wall of the bladder, rectum, and abdomen, or connective tissue, the predominant pattern is that of a nodule constituted of smooth muscle hyperplasia and fibrosis surrounding or not tiny endometrial foci or cavities [3, 14]. The appearance is similar to that of adenomyosis with secondary striking myometrial hypertrophy, and the term adenomyoma was used by some authors to describe these lesions [3, 14, 15].

17.1.4 Etiology and Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of endometriosis remains controversial. The two principal histogenetic theories are (a) metastasis of endometrial tissue to its ectopic location (metastatic theory) and (b) metaplastic development of endometrial tissue at the ectopic site (metaplastic theory). The two theories are not mutually exclusive, and it is likely that both are valid [3].

17.1.4.1 Metastatic Theory

Several ways of dissemination have been suggested:

Retrograde menstruation, that is, reflux of endometrial tissue through the fallopian tubes during menstruation, with subsequent implantation and growth on peritoneal surfaces, has been proposed by Sampson [16] to explain endometriosis. An experiment in human [17] has demonstrated that the shed endometrium is viable and may be implanted within the host. Retrograde menstruation is a common physiologic process occurring in approximately 90 % of menstruating women with patent tubes [18, 19]. Why only some of these women will develop endometriosis is not clear. Different factors have been incriminated including genetic factor, hormonal factor, menstrual factor, and immune factor [20]. Observations supporting the theory of retrograde menstruation are numerous and include the distribution of endometriotic lesions which are most common on the surfaces of the ovaries and fallopian tubes and the high frequency of endometriosis in females with congenital obstruction to menstrual flow [21–23].

Intraoperative implantation has been proposed to explain the presence of endometriosis in abdominal scars after uterine surgery [24, 25].

Hematogenous spread has been proposed to explain endometriosis in distant sites such as lungs, skeletal muscle, subarachnoid space, and kidneys, while endometriosis in lymph nodes is most easily explained by lymphatic spread [26].

17.1.4.2 Metaplastic Theory

The development of peritoneal endometriosis by a process of metaplasia of coelomic epithelium is consistent with the putative Müllerian potential of the pelvic peritoneum, which has been referred to as the secondary Müllerian system [1, 3]. Metaplasia of Müllerian remnants was also advocated as the cause of endometriosis [14]. Observations supporting the metaplastic theory include the demonstration of endometriosis in patients with Turner’s syndrome and pure gonadal dysgenesis who are amenorrheic and have hypoplastic uteri [27–30] and in males with endometriosis of the prostate, bladder, abdominal wall, and scrotum [31–33].

17.1.5 Distribution

Endometriosis can involve almost any part of the body with a notary exception, the spleen [34, 35]. However, by far, the most common locations are the ovaries and the pelvic peritoneum followed in order of frequency by the GI system and the urinary system (Table 17.1).

Table 17.1

Distribution and type of endometriotic lesions

Common lesions |

Ovaries: |

– Ovarian implant (<1 cm) |

– Endometrial cyst |

Pelvic peritoneum: |

– Implants covering the uterus, the tubes, the uterine ligaments, the anterior and posterior cul-de-sacs, the rectosigmoid, and the bladder |

Peritoneal cavity: |

– Adhesions |

Subperitoneal space: |

– Anterior with involvement of the bladder |

– Posterior with involvement of the torus, the uterosacral ligaments, the posterior fornix of the vagina, the anterior wall of the rectosigmoid junction, and the rectovaginal septum |

– Lateral involvement of the ureter (extrinsic location) |

Other GI tract locations: |

– Lower rectum and sigmoid |

Less common lesions |

Intratubal implants |

Peritoneal endometriotic pseudocysts |

Other GI tract locations: appendix, caecum, small bowel, and transverse colon |

Cutaneous: scars, umbilicus, and inguinal region |

Rare lesions |

Diaphragm |

Thoracic cavity: pleural and lung |

Other urinary tract locations: kidneys and ureters (intrinsic location) |

Other GI tract locations: gallbladder, liver, and pancreas |

Nervous system: CNS and peripheral nerves locations |

Lymphatic system: pelvic lymph nodes |

Others |

1.

Ovarian lesions may be constituted of small implants inferior to 1 cm or larger endometriotic cysts.

2.

Peritoneal implants are subdivided in superficial and deep implants.

3.

Deep infiltration is defined as the presence of endometrial tissue 5 mm or more under the peritoneum [36]. Deep infiltration leads to invasion of the subperitoneal space. The two major involved sites are (a) the anterior vesicouterine pouch with infiltration of the bladder wall and (b) the posterior cul-de-sac of Douglas with infiltration of the rectal wall, the posterior fornix of the vagina, the uterosacral ligaments, and the rectovaginal septum. The pelvic ureters are also frequently involved.

Another common manifestation of endometriosis is peritoneal adhesions that may lead to fimbriae agglutination and cul-de-sacs obliteration.

Distribution and type of endometriotic lesions are reported in Table 17.1.

17.1.6 Classification

1.

Criteria

The classification of endometriosis [37] is based on a scoring system with extensive evaluation of the site and the size of the following:

Implants of endometriosis (superficial or deep) on the ovary. Ovarian endometriotic cyst should be confirmed by histology or by the presence of the following features: (a) cyst diameter <12 cm, (b) adhesion to pelvic side wall, (c) endometriosis on the surface of the ovary, and (d) tarry thick chocolate-colored fluid content.

Implants of endometriosis on the peritoneum (superficial or deep).

Cul-de-sac obliteration is considered if endometriosis or adhesions have obliterated part of the cul-de-sac: partial, some normal peritoneum is visible below the uterosacral ligaments and complete, no peritoneum is visible below the uterosacral ligaments.

Adhesions filmy or dense of the ovary and the tube.

According to the amount of the different scores, the disease is classified as stage I (score 1–5), stage II (score 6–15), stage III (score 16–40), and stage IV (score >40).

Furthermore, this classification suggests to include information on the morphologic appearance of the implants categorized as:

1.

Red-red red-pink, and clear lesions.

2.

White-white yellow-brown, and peritoneal defects.

3.

Black-black and blue lesions.

2.

Critics

Deep endometriosis is confirmed to be poorly reflected in the revised AFS classification.

The most severe type III lesion is most frequently scored in revised AFS class I. This lends further support to Koninckx’s previous considerations for including deep endometriosis in a revision of the revised AFS classification or in a new functional classification.

17.1.7 Clinical Findings

Clinical findings are reported in Table 17.2.

Table 17.2

Clinical findings

Symptoms |

Mainly catamenial |

Common |

1. Infertility |

2. Dysmenorrhea with abdominal swelling; vomiting; and sacral, lower back pain |

3. Deep dyspareunia |

4. GI tract findings: dyschesia, diarrhea |

5. Urinary findings: dysuria, urgenturia |

Uncommon |

1. Rectorrhagia |

2. Hematuria |

3. Sciatica |

4. Right shoulder pain, pneumothorax |

Physical examination |

1. Diffuse or focal abdominal tenderness |

2. A retroverted uterus, an adnexal mass |

3. Decreased motility and/or tenderness of the uterus and ovaries |

4. Nodules or tenderness in the cul-de-sac, the rectovaginal septum, the uterosacral ligaments, and the abdominal wall |

17.1.8 Laboratory Tests

CA-125 (normal value <35 UI/ml) is commonly increased in endometriosis. It increases with the stage of the disease [38, 39]. However, this marker is also increased in many other gynecologic disorders (Table 17.3).

Table 17.3

Elevation of CA-125

1. Ovarian disease |

Epithelial ovarian tumors (borderline and carcinomas) |

Non epithelial ovarian malignant tumors |

Germ cell tumors |

Sex cord-stromal cell tumors |

2. PID |

3. Uterine disorders |

Leiomyomas |

Adenomyosis |

4. Peritoneal disorders |

Primary peritoneal carcinoma |

Peritoneal metastases |

Tuberculosis |

17.1.9 Laparoscopy

1.

Definite diagnosis of endometriosis and evaluation of its extension are usually done through laparoscopy preferably with histologic examination [43]. Laparoscopic techniques allow also surgical resection of lesions in most instances without the need to perform a laparotomy [44].

Imaging modalities are an alternative to the diagnosis and precede generally laparoscopy.

2.

Difficulties of Correlation

While the gold standard in the diagnosis of endometriosis is the presence at pathology of endometrium in an ectopic location, in routine clinical practice, difficulties in surgical pathological and radiological correlations are underestimated.

At laparoscopy, diagnosis of endometriosis can be established because the aspect of the lesion and its location are very suggestive of endometriosis (a thickening of a uterosacral ligament for instance), while no biopsy is performed. In other cases, biopsy of a suspected lesion only demonstrates fibrosis without endometrium, while the macroscopic aspect is characteristic enough to suggest endometriosis.

At laparoscopy or laparotomy, involvement of a posterior subperitoneal lesion can be overlooked because the lesion is exclusively subperitoneal in location, or can be hidden by dense adhesions, or because the lesions are so exten-sive that the surgeon gives up dissection, preventing to evaluate accurately the lesions which are clearly demonstrated on US or MR. Should these lesions depicted on US or MR be considered as false positives or rather as lesions impossible to classify as endometriotic?

17.1.10 Imaging Modalities

17.1.10.1 Methods

Two methods are essential: ultrasound and MR.

1.

Ultrasound (US) is usually performed first.

A transabdominal and a transvaginal approach must be used systematically whenever possible.

2.

MR is a complementary imaging modality in evaluating endometriosis.

Vaginal opacification is performed whenever possible. Some authors join opacification of the rectum.

The following protocol is performed:

Sagittal and axial T2 sequences.

Axial T1.

Sagittal and axial fat suppression.

Sagittal and axial T1 after injection of gadolinium.

Other methods:

CT, with IV contrast followed by opacification of the large bowel, can be performed.

1.

To make the differential between adhesion and invasion of the rectosigmoid wall and determine the extension and to look for another location.

2.

To precise the relationship of the pelvic ureters with the endometriotic lesions or adhesions and eventually to diagnose a bladder or a ureteral location.

HSG

Although less and less performed, in patients with infertility, HSG allows to evaluate the permeability of the tubes, can detect adenomyosis or tubal endometriosis.

17.1.10.2 Ovary

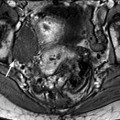

Macroscopy (Fig. 17.1) (Table 17.4)

Fig. 17.1

(1) Ovarian cyst (black arrow), (2) clots (white arrow), and (3) normal ovarian parenchyma (blue arrow)

Table 17.4

Macroscopic features and pathological surgery

Hemorrhagic content: chocolate cyst, clots |

Thickened wall |

Size <9 cm |

Shape not rounded |

Normal ovarian parenchyma pushed at the periphery |

Uni- or bilateral 1/3 to 1/2 cases |

Unique or multiple lesions |

Location backward and inward |

Adhesions to the neighboring structures or peritoneum |

1.

Hemorrhagic content. Endometriotic lesions of the ovary vary from a small focus on the surface of the ovary to a large mass. Because the ectopic endometrium bleeds, it produces a small hematoma at the surface of the ovary. Later on, this hematoma increases in size and produces an hemorrhagic cyst which progressively invaginates into the ovary pushing the ovarian parenchyma at the periphery [47] (Fig. 17.2).

Fig. 17.2

Endometriotic cyst [47]. Endometrial tufts penetrating from outside to inside into the ovary. Tunica albuginea pushed at the periphery. Adhesion created at the surface of the endometriotic cyst

2.

Thickened wall. Endometriotic cysts have typically a fibrotic wall of variable thickness, comprised between 1 and 3 mm. Its inner wall is smooth or granular [3].

3.

Size is usually between 2 and 7 cm exceptionally superior to 9 cm [49]. The smaller cysts consist of only one cavity. The larger ones can appear uni- or multilocular.

4.

The other findings will be described with the different imaging modalities.

US

US Findings

The main findings of endometrial cyst are reported in Table 17.5.

Table 17.5

Ultrasound findings of endometriomas and functional hemorrhagic cysts

Endometrioma | Functional hemorrhagic cyst | |

|---|---|---|

Size | <8 cm | <8 cm |

Shape | Not round with protrusion | Round |

Bilateral | 1/2 to 1/3 of cases | Exceptional |

Multiple cysts in the same ovary | Possible | Exceptional |

Location | – Ovarian fossa | Ovarian fossa |

– Displaced inward and backward | ||

Internal echo pattern | – Ground-glass pattern | – Fishnet pattern |

– Whirled pattern | ||

– Heterogeneous pattern | ||

Clots | – Echogenic foci | – Large hyperechoic central portion |

– Peripheral | ||

– Round or curvilinear | ||

Wall | Thick | Thick |

Layering | Possible | Possible |

Acoustic enhancement | Very common | Very common |

Follow-up ultrasound | No modification in size and echo pattern | Modification in size and echo pattern |

Normal parenchyma pushed toward the periphery | Common finding | Common finding |

Adhesions | Possible | Absence |

As far as hemorrhagic functional cyst is the main differential diagnosis, its findings are also reported in the same table.

Typical Form

1.

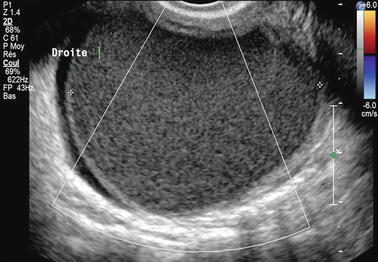

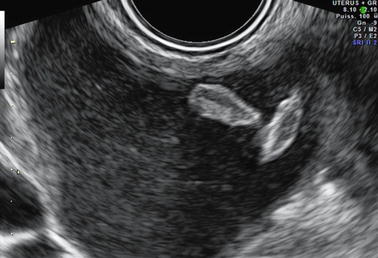

Hemorrhagic content: On transvaginal ultrasound, the hemorrhagic content of an endometrioma appears most commonly and typically as a homogeneous low-level echo pattern of lesser echogenicity than myometrium [50–52], defined by some authors as a ground-glass pattern (Figs. 17.3 and 17.4). Using this finding as the only criterion to diagnose ovarian endometriosis, it has a sensitivity of 84–95 % [53] and a specificity of 81–90 % [54].

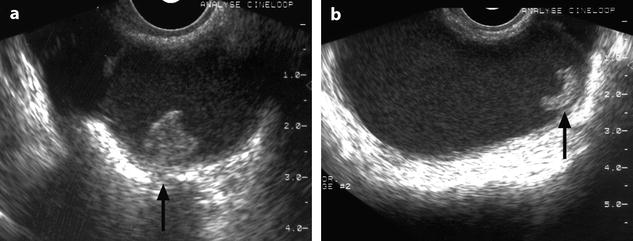

Fig. 17.3

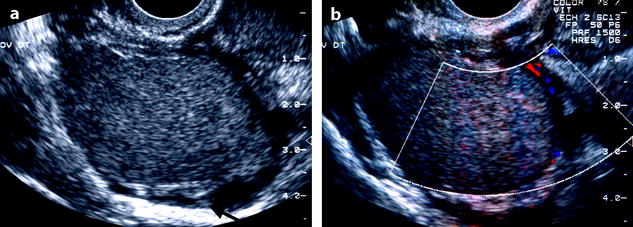

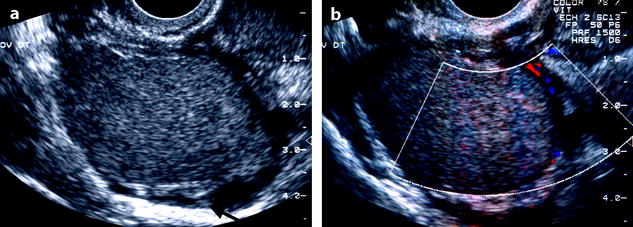

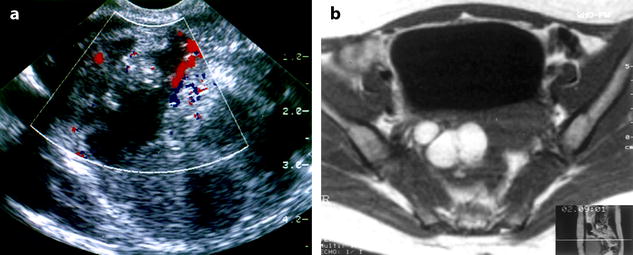

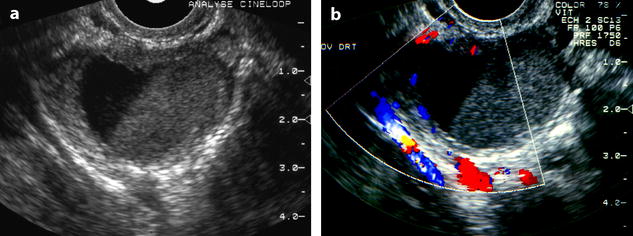

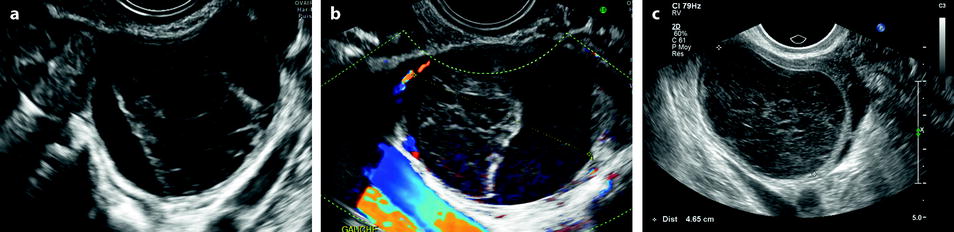

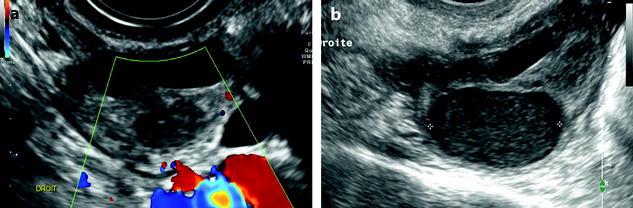

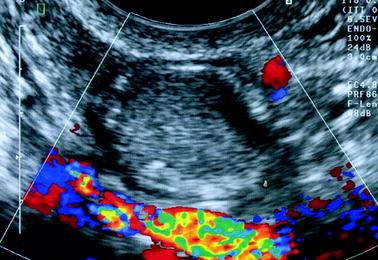

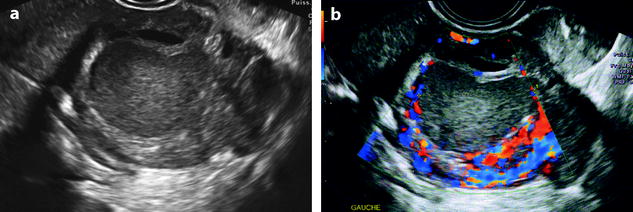

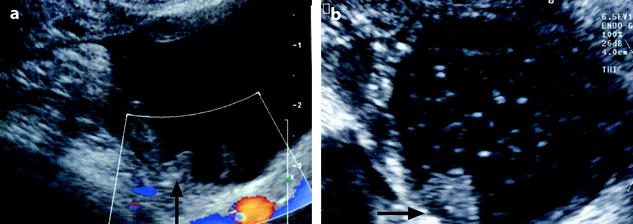

Forty-three-year-old woman, dysmenorrhea, homogeneous low-level echo, and pushing the normal ovarian parenchyma toward the periphery. Color Doppler does not display any vessel in the wall

Fig. 17.4

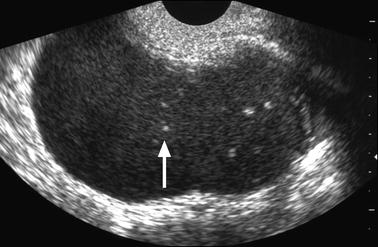

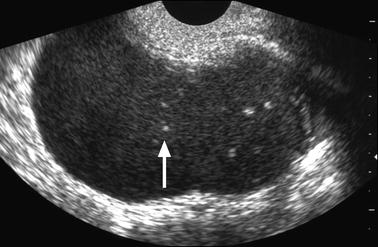

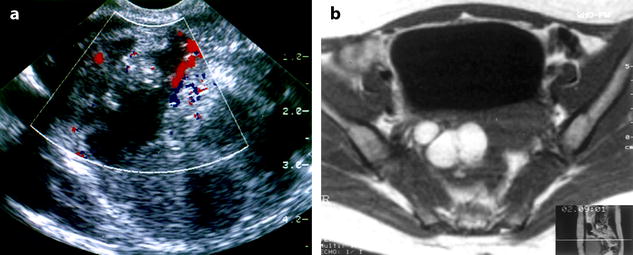

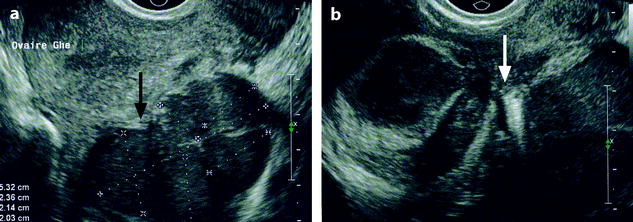

Typical echogenic pattern of endometriotic cyst on EVS. Twenty-seven-year-old woman with dysmenorrhea and CA-125 at 80 IU/ml. (a) TVS shows a 4-cm right ovarian mass with homogeneous echogenicity and an intensity lower than myometrium. Normal ovarian parenchyma (arrow) is pushed toward the periphery. (b) Color Doppler shows no vascularization in the mass proving its cystic nature. A small vessel is visualized in the wall

This pattern is very suggestive of the diagnosis but can also be found in other adnexal masses (Table 17.6).

Table 17.6

Etiology of ground-glass pattern

Common |

Hemorrhagic cyst of small size or in a portion of a larger cyst |

Mucinous cystadenoma |

Abscess |

Cystic forms of epithelial tumors with papillary projection |

Uncommon |

Dermoid cyst (a portion) |

Ovarian lymphoma |

2.

Clots: They appear as echogenic foci usually with a more intense echogenicity than myometrium but can have more rarely the same echogenicity.

(a)

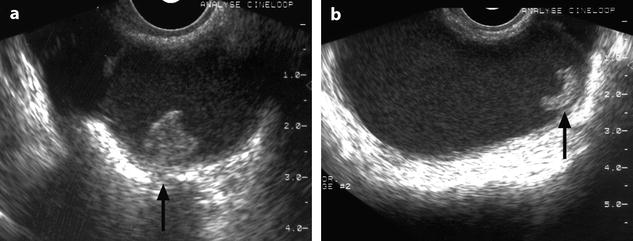

Shape: They can be round, oval (Fig. 17.5), or curvilinear (Fig. 17.6). When curvilinear, they are very typical for endometriosis [55].

Fig. 17.5

Clots in endometrioma. Clots are situated at the periphery of the cyst oval in shape, echogenic with a central lower echogenicity

Fig. 17.6

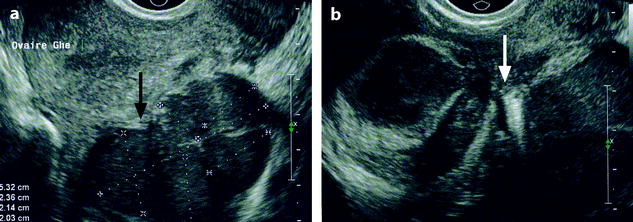

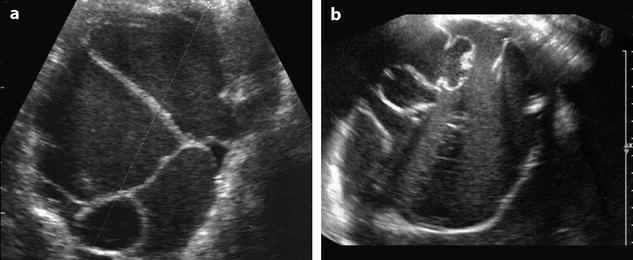

Ovarian endometrioma on US with clots. EVS Sagittal (a) and transverse, (b) show a left 8-cm cystic ovarian mass with a homogeneous low-level echoes containing semilunar clots typical of endometriomas (arrow), and with absence of vessel in the mass on color Doppler (c)

(b)

Acoustic shadowing: These clots can present without or with acoustic shadowing.

(c)

Border: Their border can be sharp or ill defined.

(d)

Size: Size is variable from some millimeters to 1 or 2 cm, rarely more.

When there are punctiform, with or without acoustic shadowing, they look like calcifications (Figs. 17.7 and 17.8); in this case, absence of vessel in the mass on color Doppler rules out a solid mass containing calcifications.

Fig. 17.7

Typical ground-glass pattern containing echogenic foci without acoustic shadowing and looking like tiny calcifications

Fig. 17.8

Anterior endometriotic cyst with clots resembling calcifications. Fifty-three-year-old woman. EVS Sagittal (a): Cystic low echogenic ovarian mass containing small hyperechoic clots (arrow) without acoustic shadowing which could have been confused with dots or lines of hair in a dermoid cyst

(e)

Location: Usually they lie against the inner wall [55] and commonly in the dependent portion but can be located more centrally.

Association of these echogenic foci to a ground-glass pattern is pathognomonic of ovarian endometriosis.

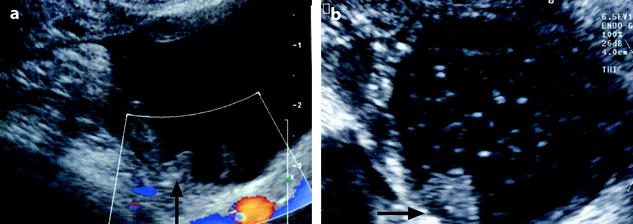

When the clot is round or oval and lies against the inner wall, it can simulate a papillary projection (BUY AJR); however, in some cases, a section in another plan can demonstrate a typical clot (Fig. 17.9). More rarely it can confused with a calcification or a tooth in a Rokitansky protuberance [56].

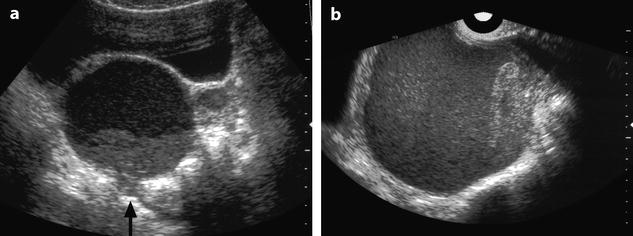

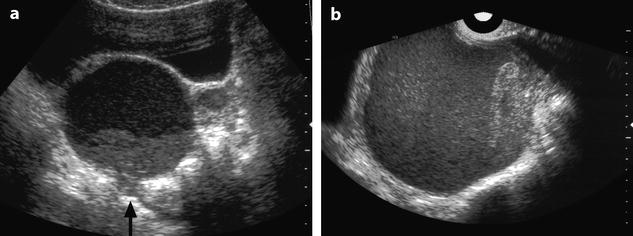

Fig. 17.9

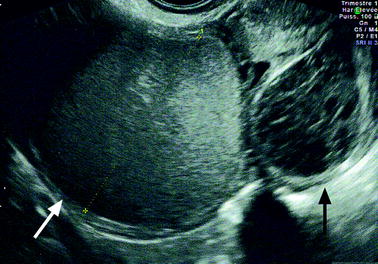

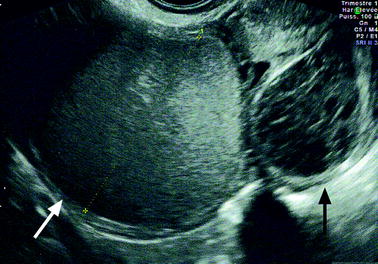

Clot simulating a papillary projection. Thirty-one-year-old woman with primary infertility and CA-125 at 117 IU/ml. (a) Coronal TVS: low echogenic ovarian cyst containing against its inner wall an echogenic focus resembling a papillary projection (arrow). (b) Longitudinal TVS: the echogenic focus appears as a semilunar echogenic clot (arrow) in the dependant portion of the mass is characteristic for endometrioma

3.

Wall: The wall of endometriomas is relatively thick (1–3 mm)compared to functional cysts and epithelial cystadenomas [52].

Acoustic enhancement can be present.

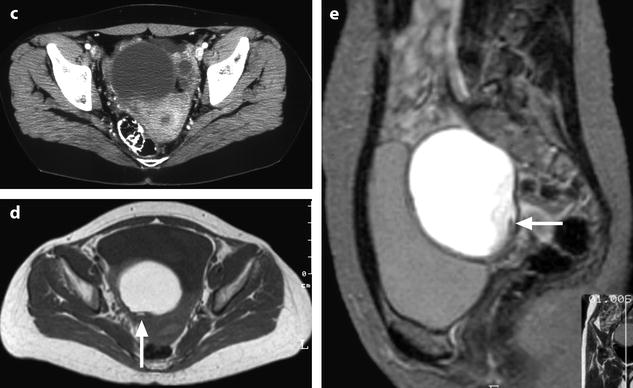

Fissure of the wall can occur (Fig. 17.10).

Fig. 17.10

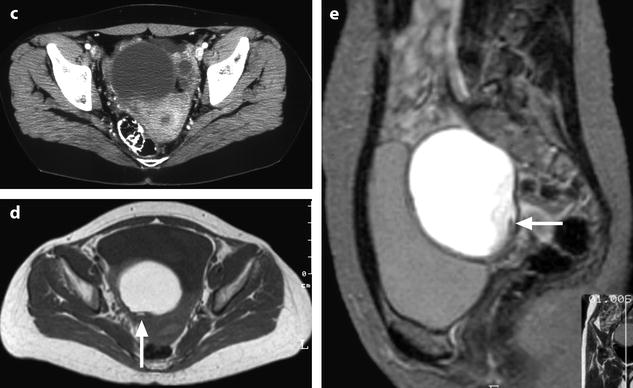

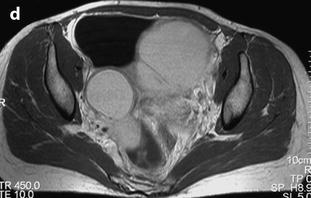

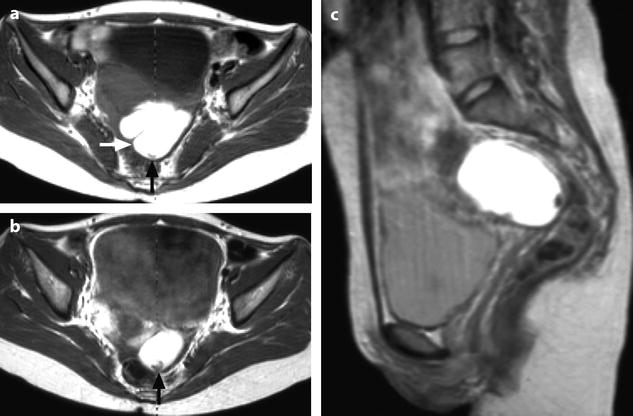

Right cystic ovarian mass with clots and an irregularity of the ontour due to posterior rupture and adhesions. Twenty-eight years old woman with pelvic mass and pelvic pain. Transverse TAS (a) (arrow) and sagittal EVS, (b) display in the posterior wall of the cyst an interruption of the wall suggesting a focal rupture. CT after injection (c) and on MR axial T1 (d) (arrow) and sagittal T2 (e) (arrow) confirm this impression

4.

Color Doppler findings: Color Doppler can show vessels in the wall of the endometrioma and in the septa. However, no vessel is seen inside the endometrioma confirming its cystic nature [50].

The Other Forms

1.

Mixed echogenic pattern (Fig. 17.11). Usually, Doppler allows to prove its cystic nature. However, in uncommon cases, the pattern is very atypical, while MR allows to make the diagnosis.

Fig. 17.11

(a) EVS with color Doppler: mixed echogenic ovarian mass with vessel in the septa. A carcinoma is discussed; (b) axial MR T1 displays a multicystic mass with a signal typical for endometrioma; coelioscopy confirmed this diagnosis

2.

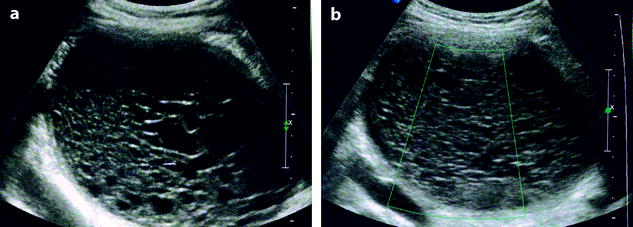

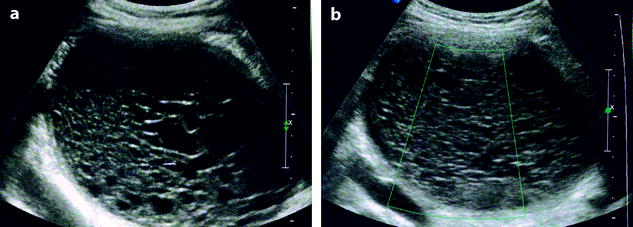

Layering (Fig. 17.12). A layering or a fluid-fluid level is an uncommon finding. It was found in 2 of 38 (5 %) endometriomas in the series of Kupfer et al. [52]. When a layering is present in a hemorrhagic cyst, a functional hemorrhagic cyst is discussed.

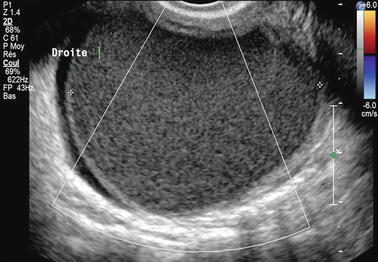

Fig. 17.12

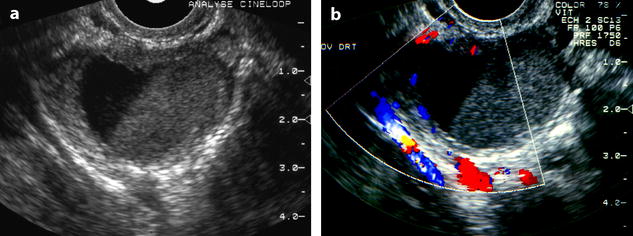

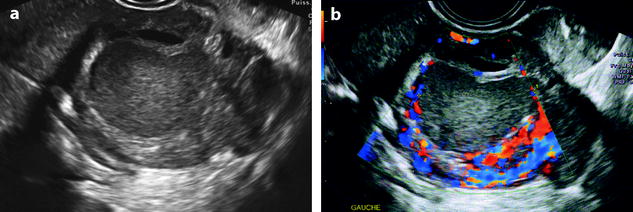

Endometriotic cyst with a fluid-fluid level. EVS without (a) and with color Doppler (b) depicts an ovarian cyst with a dependant low echogenic portion and an upper anechogenic portion; an identical pattern can be seen in FHC

3.

Atypical forms of clots and hemorrhagic contents (Fig. 17.13).

Fig. 17.13

(a) Elongated clot; (b) ground-glass pattern with a round clot; and (c) endometriotic cyst with two components, one with a ground-glass pattern and the other one with a more echogenic and homogeneous pattern

4.

Exceptionally with attenuation of the US beam simulating an ovarian fibroma (Fig. 17.14). In this case, other imaging modalities may suggest the diagnosis.

Fig. 17.14

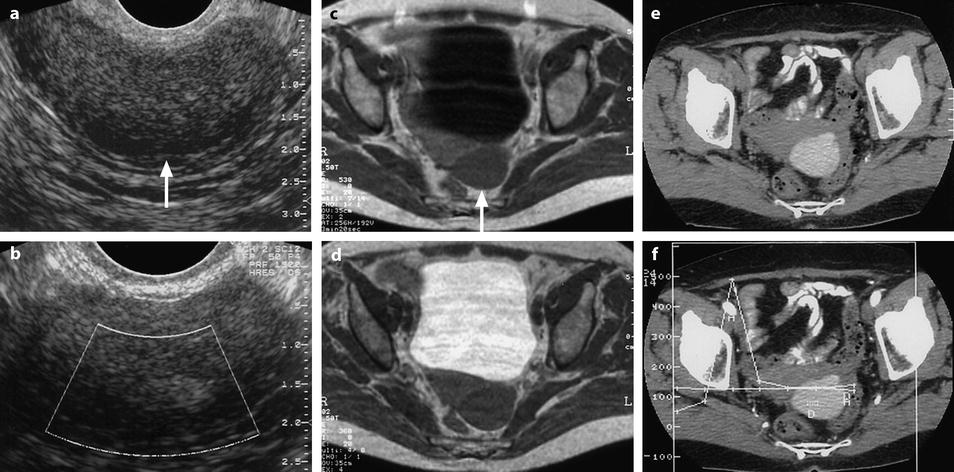

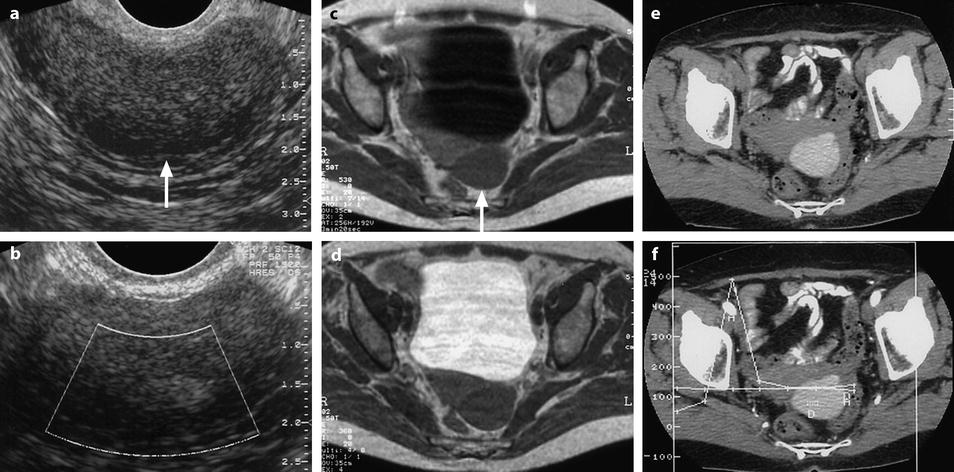

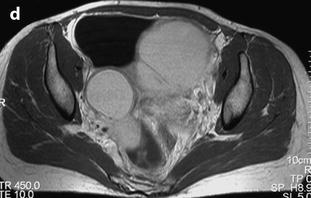

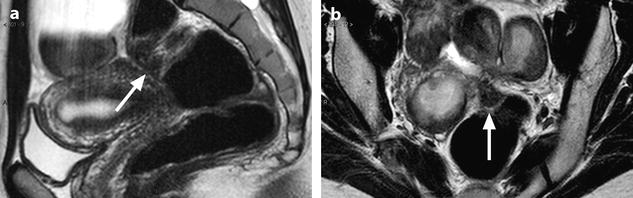

Endometriotic cyst with unusual pattern on US and on MR (low signal on T1 and T2). EVS (a) and color Doppler (b), a low echogenic mass containing a more echogenic focus is depicted. There is an overall strong posterior attenuation (arrow) in (a), suggesting an ovarian fibroma. No vessel is seen on color Doppler inside the mass. MR Axial T1 (c): left adnexal mass with signal intensity slightly superior to pelvic muscles is displayed (arrow). On T2 (d), the signal intensity of the mass is close to pelvic muscles. No definite diagnosis is proposed. CT without contrast (e) and DCT (f): cystic mass with a density of 110 HU is visualized corresponding to a hemorrhagic content. A small anterior protrusion is depicted. Prospective diagnosis: an ovarian hematoma is diagnosed on CT. The very high density excludes a functional hemorrhagic cyst. Laparoscopy: ovarian hemorrhagic cyst. Pathology: endometriotic cyst

Other US Findings Common to the Different Imaging Modalities

1.

Shape: Cysts are commonly covered by fibrous adhesions which can result in fixation to adjacent structures [3]. This is the reason why the shape of these ovarian masses, at the opposite of most primary ovarian tumors, is not rounded. The cyst conforms to the shape of the adjacent structures. In some cases, localized outward protrusions of the cyst and/or sharp inward invaginations of the cyst wall simulating incisures are very characteristic.

2.

The normal ovarian parenchyma is often seen pushed to the periphery of the lesion.

4.

Unique or multiple lesions: The lesion can be unique or multiple in the same ovary and in this last case can simulate a multilocular mass (Fig. 17.15). Invaginations or localized protrusions related to adhesions give to the mass a shape which is not round. The different loculi in the same ovary or ovarian cysts in both ovaries can appear with different echogenicities (Fig. 17.16).

Fig. 17.15

Multiloculated endometriotic cyst with sharp inward invaginations of the cyst wall simulating incisures. (a) Coronal TVS: multicystic left hypoechoic mass with a sharp incisure that looks like an incomplete septum. (b) Axial MR T1 and coronal T2 (c) definitely confirm the deep longitudinal incisure (arrow in c) in the anterior part of the mass. This incisure is related to adhesions, which are very characteristic of endometriomas

Fig. 17.16

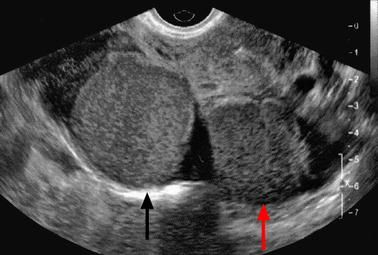

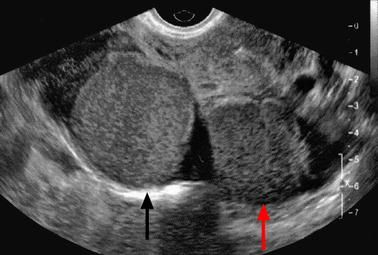

Bilateral endometriotic cyst with different echogenicities. Right (black arrow) and left ovarian (red arrow) cysts have different echogenicities

5.

Location is variable. The mass can be in the ovarian fossa. However, because of the retraction inflammatory in origin and adhesions, the mass has a tendency to be situated more backward and inward. When the mass is in such a situation and bilateral, cysts are opposed to each other tethering the rectosigmoid. This topography is very characteristic; however, one can also see it in case of bilateral carcinomas of the ovary. Exceptionally, the mass is anterior to the broad ligament.

6.

Adhesion to the neighboring structures or to the peritoneum is very common (Fig. 17.17).

Fig. 17.17

Adhesion. Longitudinal EVS (a) displays adhesion of a left ovarian endometriotic cyst to the posterior wall of the uterus (black arrow). Axial EVS (b) depicts a right multilocular and a left unilocular ovarian endometriotic cyst with adhesion to the torus (arrow)

7.

Stability of the internal echo pattern: Endometriomas do not resolve or diminish in size during a short period of time, and their internal echo pattern is stable.

Differential Diagnosis

The main differential diagnosis is reported in Table 17.7.

Table 17.7

Differential diagnosis

Common |

The other adnexal cystic echogenic masses |

Functional hemorrhagic cyst |

Dermoid cyst |

Mucinous cystadenoma |

Tuboovarian abscess |

Cystic epithelial ovarian tumor with papillary projection |

The echogenic solid ovarian masses |

Ovarian fibrothecoma |

Subserous leiomyoma |

Uncommon |

Lymphoma and metastases |

The Other Adnexal Cystic Echogenic Masses

1.

Functional hemorrhagic cyst (Table 17.5):

(a)

The patterns of FHC are very variable.

Some echogenic patterns are typical for functional hemorrhagic cysts: Fishnet appearance, a central clot related to the periphery with thin echogenic lines, and a small echo-free area in an echogenic cysts [50, 51, 57] (Fig. 17.18).

Fig. 17.18

(a) Central clot typical for FHC, (b) color Doppler does not display any vessel in the clot, and (c) characteristic fishnet appearance

However, in some cases, differentiation with endometrioma can be very difficult. Some aspects of echogenic cysts suggestive of FHC are very uncommonly related to endometriosis (Fig. 17.19). Very similar small echogenic cysts can be related to FHC and endometriosis (Fig. 17.20).

Fig. 17.19

(a) Endometriotic cyst with absence of vessel on color Doppler (b)

Fig. 17.20

EVS (a) Endometrioma, (b) functional hemorrhagic cyst with a ground-glass pattern

Not exceptionally, FHC and endometriotic cyst can be associated in the same ovary or in the contralateral ovary (Fig. 17.21).

Fig. 17.21

Association of a FHC and an edometriotic cyst in the same ovary. Association of a FHC with a characteristic fishnet appearance (black arrow) and endometriotic cyst with a typical ground-glass (white arrow) pattern in the same left ovary

(b)

On ultrasound follow-up, functional hemorrhagic cysts not only have a tendency to resolve or diminish in size but their internal echo pattern is modified. In Okai et al. series [57], 7 of 24 functional hemorrhagic cysts (29 %) disappeared within 2 weeks, and the remaining had different sonographic appearance with time until they disappeared finally within 8 weeks.

2.

Dermoid cyst: While some echogenic patterns like a highly echogenic focus with broad acoustic shadowing, a hair ball, or an entirely hyperechoic mass are very suggestive of the diagnosis, the echogenic pattern can be less characteristic especially when the mass is relatively uniformly echogenic; in this case, dermoid cyst can mimic an endometrioma (Fig. 17.22).

Fig. 17.22

Atypical dermoid cyst looking like endometriosis. The cyst with a ground-glass pattern considered as an endometriotic cyst was in fact a dermoid cyst

3.

Mucinous cystadenoma when unilocular can be difficult to differentiate from endometrioma. Accumulation of mucin can resemble clots (Fig. 17.23).

Fig. 17.23

(a) Multilocular endometriotic cyst and (b) multilocular mucinous cystadenoma

4.

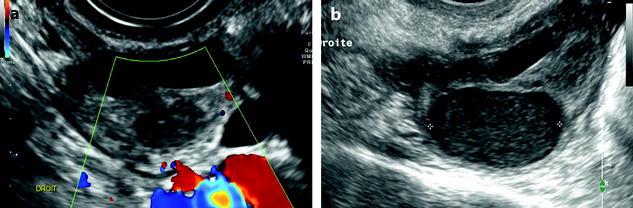

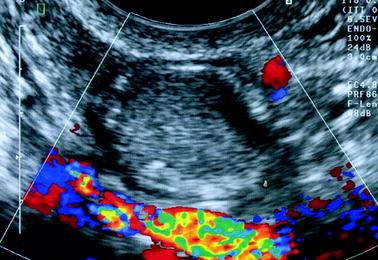

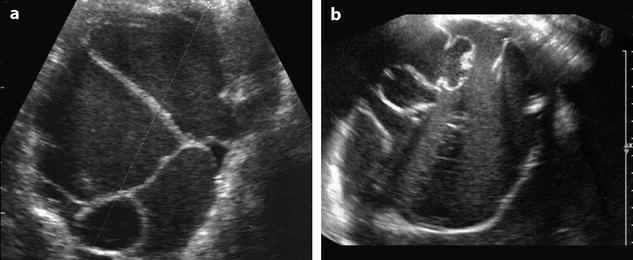

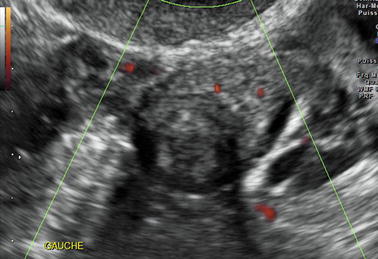

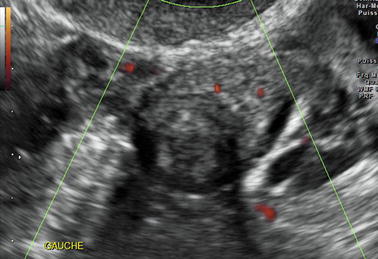

Ovarian abscess can look like exactly like an ovarian endometrioma (Fig. 17.24). However, usually a significant peripheral vascularization is present.

Fig. 17.24

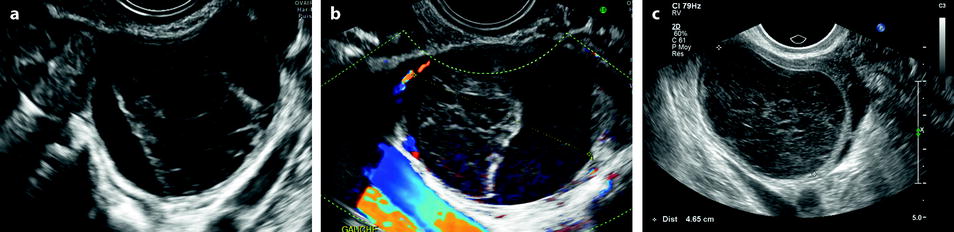

EVS without (a) displays a low-level echogenic mass. Color Doppler (b) depicts a peripheral hypervascularization, very suggestive of an abscess

The Echogenic Solid Ovarian Masses

1.

Ovarian fibroma. When small, without degenerative changes, ovarian fibromas can present relatively uniform echogenic pattern (Fig. 17.25). Two main findings allow to make the differential: (1) numerous discrete acoustic shadowing not related to calcifications but to fibrous tissue and (2) color Doppler usually demonstrates vessels in the mass which typically are scarce and central, but in some cases, vessels are barely seen. DMR makes the diagnosis.

Fig. 17.25

Low-level echogenic ovarian mass; although a slight attenuation is displayed, the diagnosis of ovarian fibroma cannot be ascertained

2.

Pedunculated subserous leiomyoma can also appear as a homogeneous echogenic mass. As ovarian fibroma, it may present numerous discrete shadowing.

Its vascularization is richer than that of ovarian fibroma often realizing a peripheral hypervascular rim. Other findings that allow to differentiate uterine subserous leiomyoma from ovarian fibroma and ovarian endometrioma are (a) visualization of a normal ipsilateral ovary and (b) a vascular pedicle linking the mass to the uterus.

3.

Less commonly, the epithelial cystic tumors with papillary projections particularly the borderline and malignant forms (Fig. 17.26).

Fig. 17.26

(a) EVS with color Doppler: endometriotic cyst, containing multiple clots lying against the inner wall of the cyst (arrow). These clots can simulate papillary projections like in this case of mucinous cystadenofibroma (arrow in b). Color flow (in a) is absent in the clots

When a clot lies against the inner wall of a cyst, it can resemble in some cases to a papillary projection. When this echogenic focus is superior to 1 cm in diameter, color doppler usually demonstrates color flow in the papillary projection while color flow is absent in the clot. On the opposite, when the echogenic focus is inferior to 1 cm in diameter, differential diagnosis may be impossible as far as color flow is absent in both. In these cases, injection of IV contrast on MR usually depicts contrast uptake in the papillary projection.

MR

After US examination, MR is advocated:

1.

For the diagnosis, (a) when the clinical findings are very suggestive of endometriosis while the US is normal, (b) when the cysts are of small size, and when the pattern of the ovarian cyst is not sufficiently characteristic to diagnose endometriosis.

2.

To evaluate extension particularly to look for or to confirm subperitoneal locations.

3.

For the follow-up under medical treatment or to diagnose a recurrence.

MR Findings

It is practical to distinguish small intraovarian implants (<1 cm) and larger endometrioma (>1 cm).

Endometrioma

1.

2.

Hemorrhagic content:

The main findings are reported in Table 17.8.

Table 17.8

Signal intensity of endometriomas on T1, T1 with fat suppression, and T2

T1 | T1 with fat suppression | T2 |

|---|---|---|

Signal ≥ adipose tissue | High signal in 100 % | Intermediate signal, between pelvic muscle and adipose tissue |

Signal ≥ urinea | ||

Muscle < signal < adipose tissue | High signal | Signal ≥ urine |

Low signal | Signal < adipose tissue | |

Signal = muscle | Low signal | Signal = pelvic muscle |

1.

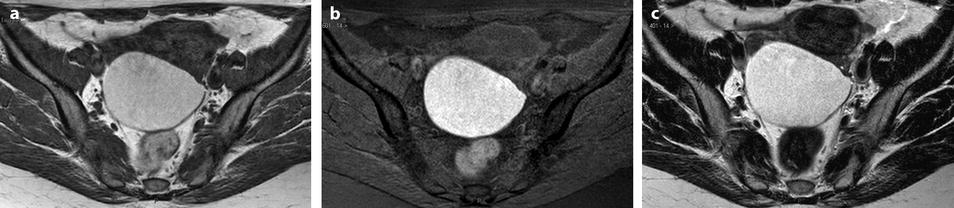

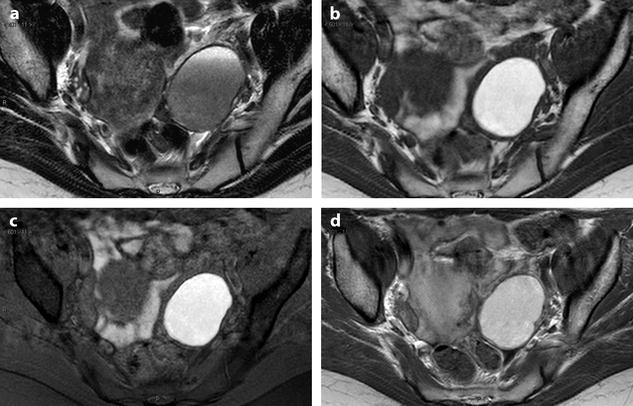

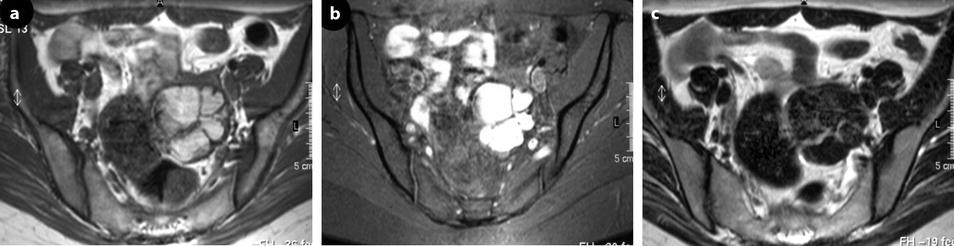

The most common form of presentation present in 80/86 (93 %) [60] and the most characteristic (Figs. 17.27 and 17.28).

Fig. 17.27

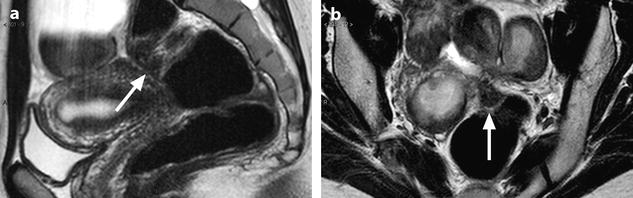

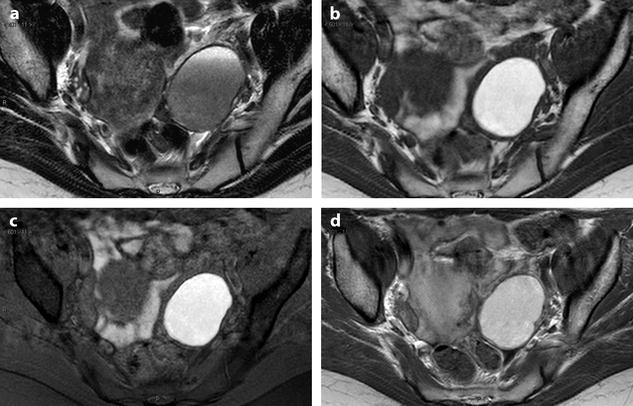

MR characteristic pattern bilateral multicystic ovarian endometriotic cyst. MR axial T1 (a) fat suppression (b), T2, and (c) after injection (d). The content of the cysts has a signal identical to fatty tissue on T1 (a) with a high signal on fat suppression (b) and a decrease of the signal on T2 with an intermediate signal between adipose tissue and pelvic muscle. Association of these findings is specific for endometriosis; after injection there is a slight contrast uptake in the wall of the cysts. Bilaterality and presence of multiple cysts in the ovaries are characteristic additional findings

Fig. 17.28

MR sagittal T2 (a) and axial T2 (b) display a tissular mass in the anterior portion of the sigmoid (arrows). Bilateral endometriotic cyst is associated. Axial T1 (c) and sagittal T1 after injection (d) depict contrast enhancement in the lesion. CT with enema: Sagittal reformation (e) and axial view (f) confirms the presence of an endometriotic location in the anterior portion of the sigmoid (arrows in e and f); the irregular aspect of the mucosa precises that the lesion extends deeply at least into the muscular layer. Enema also allowed to precise that this location was unique, which was confirmed at operation

On T1W images, a predominantly high-signal intensity ≥ adipose tissue. The cyst can be homogeneously hyperintense or heterogeneous because the blood products are in various stages of degradation from multiple episodes of bleeding.

On fat suppression, a high-signal intensity is maintained in 100 % of cases [59, 61], allowing to rule out fatty content present in dermoid cyst or immature cystic teratoma.

On T2W images:

(a)

In the characteristic form, the overall signal becomes lower, intermediate between adipose tissue and pelvic muscle. While the signal in almost all ovarian cysts increases on T2, this decrease in signal on T2 is very particular to endometrioma. This decrease in signal is homogeneous (Fig. 17.27) or heterogeneous (Fig. 17.28).

This T2 shortening has been designated the shading sign [58]. Shading is a focal [58] or diffuse [62] or appears as a loss of signal in the dependant layering with a hypointense fluid level [60]. When it is focal, it can be located peripherally or centrally with a relatively sharp margin from the high-signal intensity loculize content or marge imperceptibly with it [58]. It can be attributable to the highly viscous content of the cyst or to the extremely high concentration of methemoglobin or a high protein concentration [60] or iron products.

In a cystic mass, association of an overall signal equal to adipose tissue on T1, a high signal on fat suppression, and a decrease signal on T2 comprised between adipose tissue and pelvic muscle is almost pathognomonic for diagnosis of endometrial cyst+++.

(b)

On T2W images, a hyperintense signal can be present like in a chronic stage hematoma and in this case, is considered not definite but very suggestive of endometriosis [60, 63] (Fig. 17.29).

Fig. 17.29

Endometriotic cyst with a high signal on T1 and T2. Forty-three-year-old woman with dysmenorrhea. MR axial sequences: right ovarian cyst with a signal comprised close to adipose tissue on T1 (a) with a high signal on fat suppression (b) and a high signal close to urine on T2 (c)

After injection, a slight contrast uptake is visualized in the wall.

2.

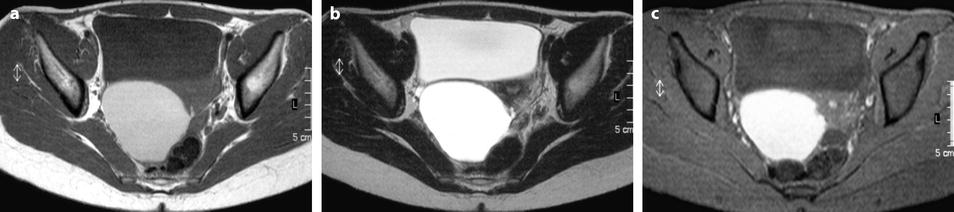

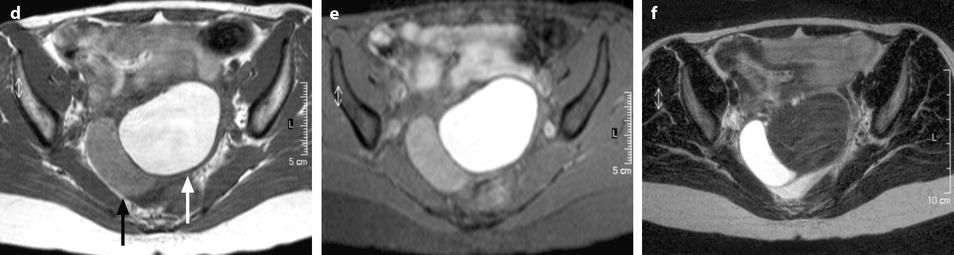

Uncommonly, on T1W images, the signal is intermediate comprised between muscle and adipose tissue (Fig. 17.30).

Fig. 17.30

Ovarian cyst with an intermediate signal on T1. MR axial T1 (a) fat suppression (b) and axial T2 (c): content of the cyst has an intermediate signal on T1, a high signal on fat suppression and a signal close to urine on T2. On sagittal T2 (d): protrusion of the lower part of the cyst, an additional characteristic finding of endometriosis, is displayed (arrow)

On fat suppression, the cysts may have a high or a low signal [63].

3.

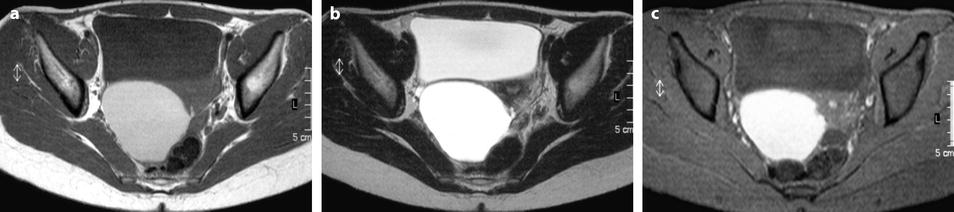

Clots: The morphologic findings are the same as those mentioned on ultrasound (paragraph ultrasound) (Fig. 17.31).

Fig. 17.31

Characteristic semi-lunar clot in an endometrial cyst. Thirty-one-year-old woman with primary infertility and CA-125 at 117 IU/ml. (a) MR axial T1: the mass appears with a irregular contour and a characteristic indentation (white arrow). Signal intensity is equal to adipose tissue. A semi-lunar clot is visualized in the dependant portion of the cyst with a signal slightly superior to pelvic muscles (black arrow). (b) MR axial T1 after contrast injection. No contrast uptake is depicted in the semi-lunar focus confirming it is related to a clot (arrow). (c), sagittal T2. The cystic content has a signal intensity superior to urine. The clot has a signal equal to pelvic muscles (). Marked irregular contour are related to adhesions

Signal intensity of the clots is either equal to muscle [55] or comprised between muscle and adipose tissue on both T1- and T2-weighted images. Absence of contrast uptake allows to distinguish a clot from a papillary projection.

4.

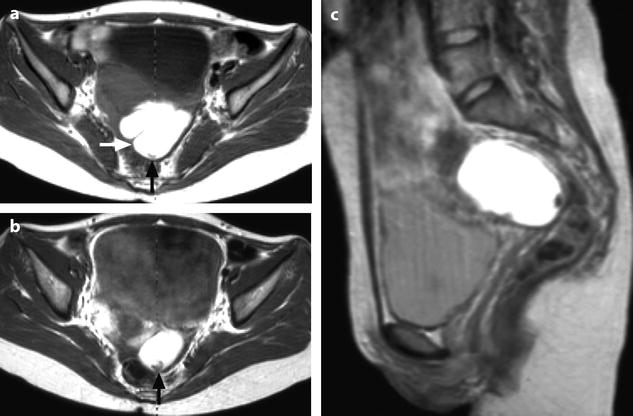

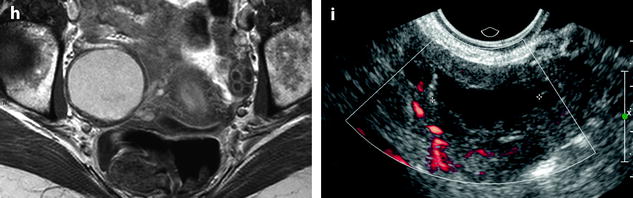

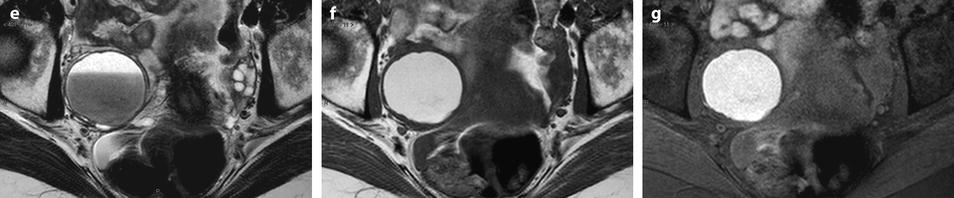

While layering can be observed in functional hemorrhagic cyst [65], exceptionally this finding can be observed in endometrioma [58, 60, 66] (Fig. 17.32). The dependent portion had a low signal in 2/12 endometriomas on T1-weighted images and in 10/12 endometriomas on T2-weighted images in Zawin et al. series [66].

Fig. 17.32

Differential diagnosis between endometrioma and functional hemorrhagic cyst. Endometriotic cyst in one patient: MR axial on T1 (a) displays a 5.5 cm left ovarian cyst with an intensity close to adipose tissue a high-signal intensity on fat suppression (b) with a decrease of signal which is intermediate with a fluid level on T2 (c) which is typical for an endometriotic cyst; a slight contrast uptake in the wall is displayed after injection (d). Fig. 17.32 (continued) Functional hemorrhagic cyst in an other patient: MR axial T1 (e) Fat suppression (f) T2 (g) and after injection (h) display a 5 cm right ovarian cyst which has exactly the same features of signal, suggesting an endometriotic cyst; because of the rapid increase in size (this cyst measured 3 cm on a US performed 2 months earlier), a functional hemorrhagic cyst could not be excluded. EVS (i) performed at the beginning of the next cycle demonstrated a significant decrease in size of the cyst associated with a flattened pattern proving the functional nature of the cyst. This pattern in MR is quite unusual, but outlines in some cases the necessity to perform an ultrasound examination after the next period to make the differential diagnosis

In very common cases, signal intensity of the FHC can be the same as endometriosis; only the follow-up with US can make the differential diagnosis (Fig. 17.32).

5.

Other MR findings common to the different imaging modalities.

The shape: Inward invaginations of the wall simulating incisures, localized outward protrusions, and irregularity of the external wall are related to peripheral adhesions and are typical for endometriomas.

Bilateral topography is very suggestive.

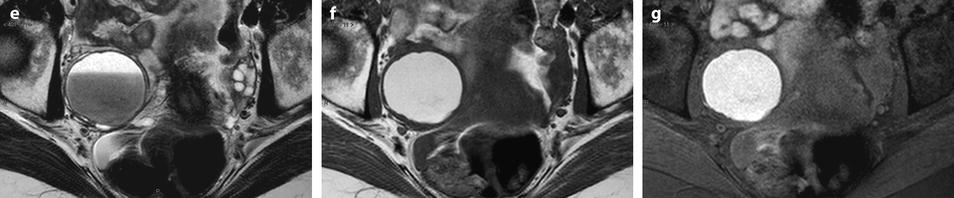

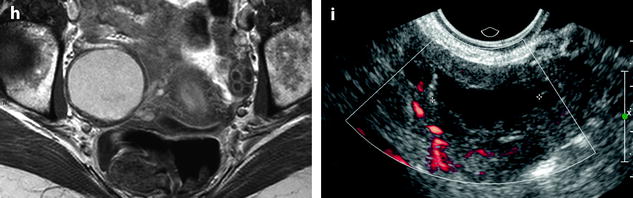

Multiple lesions considered by Togashi et al. [58, 60] as typical for endometriomas and are better visualized on MR (Fig. 17.33).

Fig. 17.33

Multicystic left endometioma. Thirty-four-year-old woman with dysmenorrhea. (a), MR axial T1: a 5-cm left ovarian multicystic mass with an overall signal close to adipose tissue. (b) axial T1 with fat suppression: an overall bright signal is seen in the mass confirming its hemorrhagic nature. (c) axial T2: the signal in the mass is significantly decreased. Multiplicity of hemorrhagic cysts allows the definite diagnosis of endometriosis. Diffuse superficial peritoneal implants in the sub-diaphragmatic spaces and the paracolic gutters not evaluated by MR, were discovered at surgery

Precise location of the mass is also better depicted on MR than on ultrasound.

Adhesions can be highly suspected when (1) obliteration of Douglas outlined by an incompletely declive peritoneal effusion is present; (2) the cysts are posteromedially situated, due to retraction of the posterior leaf of the broad ligament, giving in case of bilateral lesion(s) a typical tethered aspect of the rectosigmoid; and (3) when a plane separating two contiguous anatomic structures is obliterated on T2 and after injection, mainly when there is an associated attraction; however, this last finding can be over or underestimated.

Intraovarian Implants (Endometriomas <1 cm)

Impossible to detect and especially to characterize on ultrasound, they can be visualized as hyperintense foci on T1-weighted images coupled with fat suppression [67]. They have variable intensity on T2-weighted images. Even, when they are tiny, they can be detected because of the high contrast between them and the ovarian parenchyma. They can be totally overlooked by laparoscopy.

When these implants are unique and unilateral, they lack of specificity and can correspond to a corpus luteum cyst or small hemorrhagic follicles. That is why, MR should be performed in the first part of the cycle when possible.

Differential Diagnosis

1.

Functional hemorrhagic cyst. Three main aspects can be observed.

(1)

In the most common and characteristic form of FHC (Table 17.9):

Table 17.9

Differential diagnosis endometrioma versus FHC

T1 | Fat suppression | T2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

Endometrioma | = Adipose tissue | Elevated | Decrease between adipose tissue and muscle |

FHC | = Muscle | Low | High signal ≥ urine heterogeneous |

(2)

Uncommonly, signal intensity is comprised between muscle and adipose tissue on T1-weighted images, with high signal on T1-weighted fat suppression images and a signal superior or equal to urine on T2-weighted images [68]. This pattern can be observed occasionally in endometrioma.

Layering is more frequent in functional hemorrhagic cysts than in endometriomas.

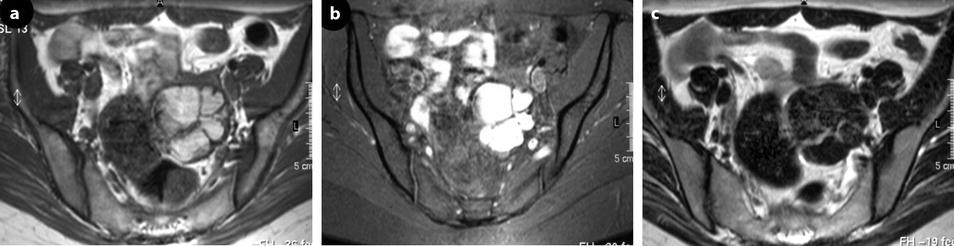

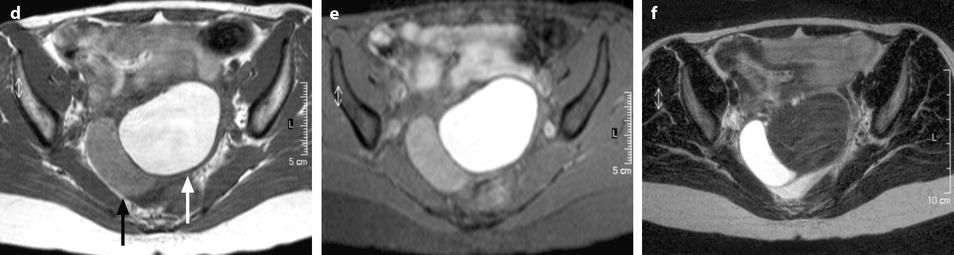

Endometrial cyst is not exceptionally associated with FHC in the same (Fig. 17.34) or in the contralateral ovary.

Fig. 17.34

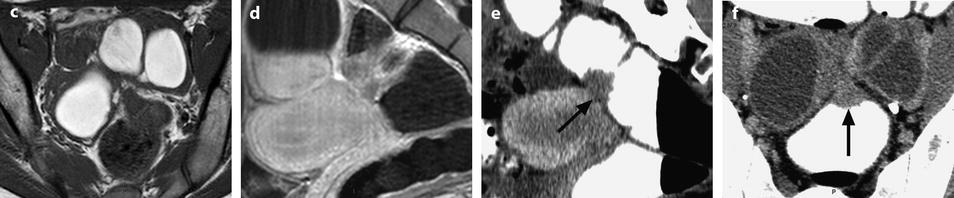

Association of a FHC and an endometrioma in the same ovary. EVS transverse of the right ovary (a) and sagittal through the lateral cyst (b) and through the medial cyst (c) displays a lateral cyst l with typical findings of a hemorrhagic functional and a typical medial endometrioma. MR axial T1 (d), fat suppression (e) and T2 (f) depict: (1) a lateral cyst with an intermediate signal on T1and fat suppression and a signal close to urine on T2; these findings are typical for a FHC (black arrow). (2) In the medial part of the ovary a cyst with a signal close to adipose tissue on T1 (white arrow), with a high-signal intensity on fat suppression, and an intermediate signal between adipose tissue and pelvic muscle (decrease of the signal) onT2; these findings are typical for an endometrioma

Dermoid cyst. This differential does not include the regular dermoid with signal ≥ adipose tissue on T1 with low signal on T1 fat-suppression sequences but dermoids with signal inferior to adipose tissue on T1-weighted images. CT can be very helpful in this last case in demonstrating small areas of low density of fat or a Rokitansky protuberance.

Mucinous cystadenoma, which can be a problem on US, has usually a different patten on MR. In case of the most frequent multiloculated form, on T1-weighted, the loculation with the highest signal is comprised between muscle and adipose tissue. On fat suppression, the signal is intermediate. On T2, the different loculi are of different signals.

In case of the unilocular form on T1, the signal is comprised between muscle and adipose tissue. On T2, the signal is ≥ urine.

Ovarian abscess. On T1, signal is intermediate between pelvic muscles and adipose tissue.

On fat suppression, a very high signal can be confused with the signal of an endometrioma.

On T2, the signal is high as urine.

After injection, there is a characteristic high-contrast uptake in the wall on the delayed phase associated with a blurring at the periphery of the lesion (see Chap. 33).

Ovarian fibroma. This differential diagnosis is only discussed in the exceptional cases of endometriomas with signal equal to muscle on T1. Delayed contrast uptake is displayed in a fibroma [71].

Epithelial cystic mass with papillary projection. When an endometrioma contains a clot lying against its wall, an epithelial cystic mass with papillary projections is a differential diagnosis. However, (1) the cystic content in case of borderline or carcinoma has a signal usually comprised between pelvic muscle and adipose tissue and (2) injection of gadolinium always demonstrates a contrast uptake in the papillary projections.

CT Pattern

CT has no place in the current diagnosis of endometrioma. However, because endometriosis can be discovered by chance on a CT examination and because endometrioma can be a differential diagnosis with other adnexal masses where CT has major indications, the aspect and the main findings of endometrioma on CT must be known.

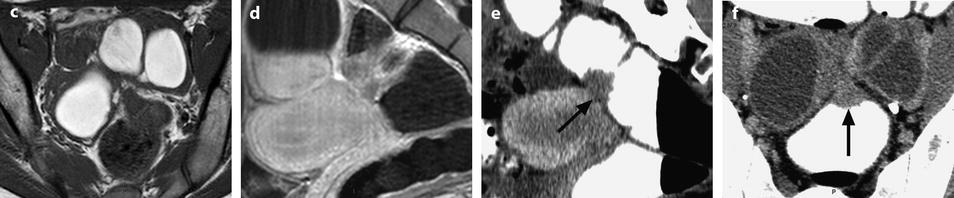

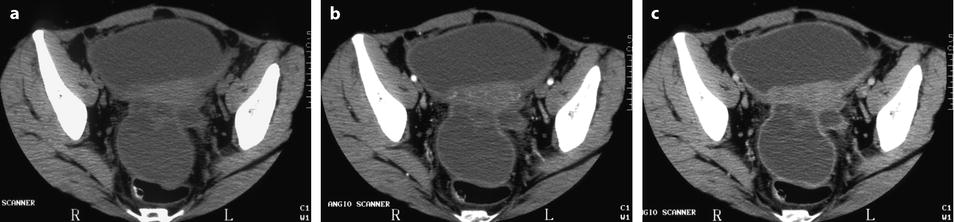

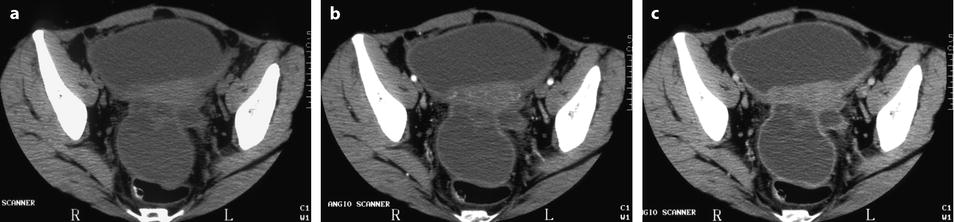

The wall: Without injection, the wall can be dense; the external surface may have a blurred appearance due to adhesions, while the inner wall may have a shaggy appearance due to small clots against its inner wall (Fig. 17.35). After contrast injection, contrast uptake is visualized in the inner wall, external wall remains blurred at the arterial phase of a dynamic CT injection, and regular vessels are usually visualized giving the wall a double contour aspect.

Fig. 17.35

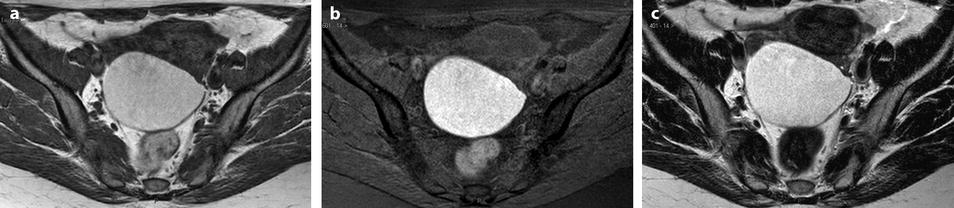

Bilateral ovarian endometrioma typical aspect on DCT. CT without contrast (a): the walls of the cysts are slightly denser than the cystic content. Hyperdense foci (arrow) related to clots lie in the dependent portion of the left cyst. At the arterial phase (b): tiny vessels (arrow) are visualized in the inner walls. At the parenchymal phase (c): contrast uptake in the walls is depicted

The hemorrhagic content: Without contrast, density of the cyst is usually higher than that of urine and close to myometrium (Fig. 17.36). After contrast, absence of contrast uptake in the cyst easily allows to prove its cystic nature.

Fig. 17.36

CT findings of hemorrhagic content in endometrioma. DCT without injection (a): the cyst is not round; its wall is thick; and density of the content is 20 HU, related to the hemorrhagic content. At the arterial phase (b), a regular vessel is seen in the wall, with a contrast uptake at the venous phase (c) which is more pronounced on the delayed (d)

Exceptionally, the overall density of the cysts is very high, around 100 HU (Fig. 17.14). These cases are also correlated with very peculiar aspects on ultrasound and MR.

Clots: They appear with the different shapes described above. They can resemble to calcifications; however, their density is usually comprised between 90 and 140 HU [55] which is much lower than regular calcifications. Their exact location, separate from the wall, can clearly be seen and a particular semilunar shape is specific for endometrioma (Fig. 17.37).

Fig. 17.37

Characteristic curvilinear clot on CT. (a) In vivo CT scan: a characteristic declive curvilinear clot in the dependent portion of an ovarian endometriotic cyst is displayed (arrow). (b) In vitro CT scan: density of the clot measures 90 HU (arrow)

Differential diagnosis: Except in the case where a typical clot is found or where secondary findings such as bilateral and multiple lesions, localized protrusions, and incisures are seen (Table 17.2), the diagnosis can hardly be made on CT.

17.1.10.3 Subperitoneal Endometriosis

Deep endometriosis is defined by some authors as an infiltration of the implant penetrating ≥5 mm under the surface of the peritoneum [36]. In fact, any type of endometriotic lesion under the peritoneum is considered as a subperitoneal location.

The depth of an endometriotic lesion cannot be anticipated at coelioscopy. A small pelvic lesion can hide a deep and larger endometriotic lesion, especially in types II and III [72]. Deep endometriosis is poorly reflected in the AFS classification.

As it has been already mentioned, the pattern of endometriotic lesions is quite different according to the tissue in which endometriosis develops. Indeed in the subperitoneal space, endometriotic implants grow in conjunctive tissue, which is quite different from stroma of the ovary.

Macroscopy and Imaging Findings

They are reported in Table 17.10.

Table 17.10

Macroscopic and imaging findings

1. US |

1. Fibromuscular component echogenic or hypoechoic |

2. Endometriotic foci: may appear hyperechoic or anechoic |

2. MR |

1. Fibromuscular component: |

T1, fat suppression, and T2. Overall signal close to pelvic muscle or of intermediate signal |

After injection, fibrotic component slightly enhances |

2. Endometriotic foci: |

Hemorrhagic foci: high signal on T1, after fat suppression, and variable signal on T2 |

Cavities containing a clear fluid: low signal on T1 and a high signal on T2 |

The pattern of the lesion is mainly related to the fibromuscular hyperplasia surrounding the endometriotic foci that can contain small cavities [36].

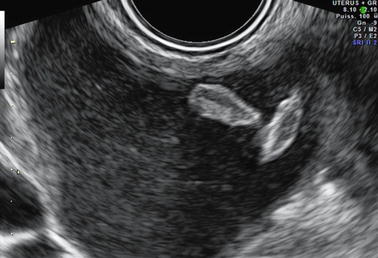

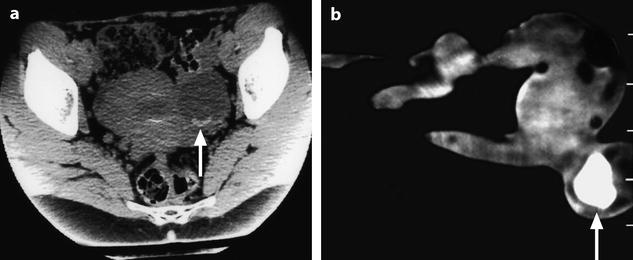

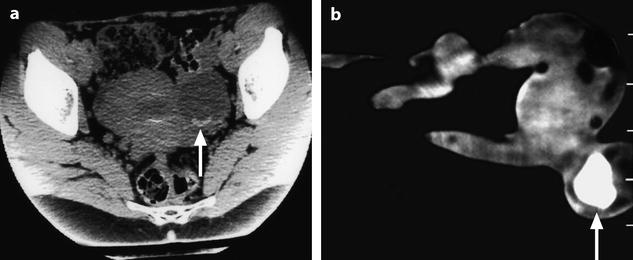

Subperitoneal endometriosis (Fig. 17.38) can involve:

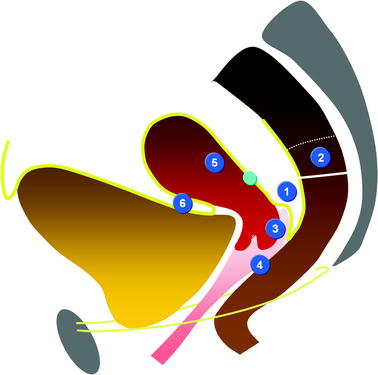

Fig. 17.38

(1) Torus and US, (2) rectum, (3) cervix, (4) vagina, (5) uterus, and (6) vesicouterine pouch

1.

The posterior subperitoneal space, most often secondary to peritoneal implants in the pouch of Douglas that extends into the vaginal fornix; the anterior wall of the rectum; the rectovaginal wall; and laterally, the uterosacral ligaments.

2.

The anterior subperitoneal space, mainly the bladder wall secondary to implants in the vesicouterine pouch Sampson.

3.

The lateral subperitoneal space.

Posterior Subperitoneal Space

Anatomy

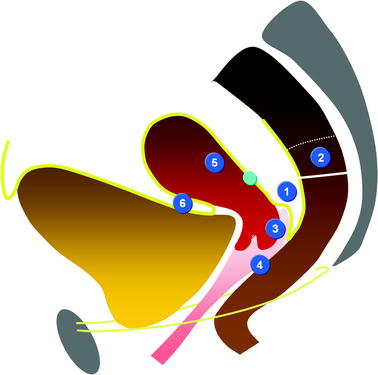

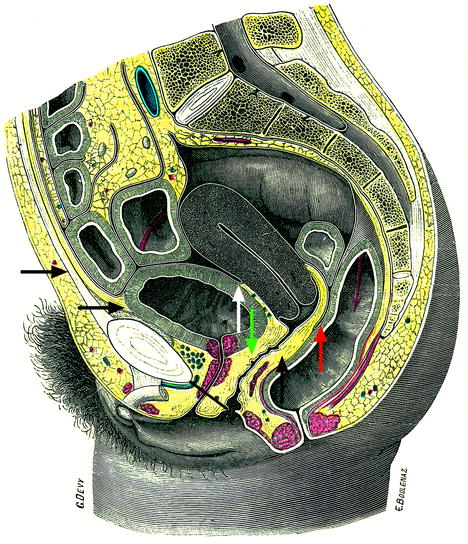

On the midline: (Figs. 17.39 and 17.40)Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Fig. 17.39

Intraperitoneal space (indicated in front of the superior horizontal black arrow), anterior subperitoneal space (inferior horizontal black arrow), perineal space (below the black bar), vesicouterine pouch (white arrow), vesicouterine septum (green arrow), Douglas (a little above the tip of the red arrow), and rectovaginal septum (vertical black arrow)

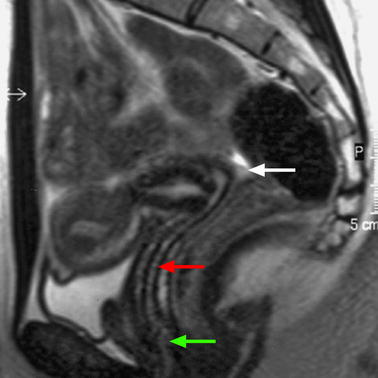

Fig. 17.40

Sagittal T2 through the midline (B): Three different compartments from upward to downward are visualized: (1) The intraperitoneal space with the pouch of Douglas (white arrow) with its lower part at the level of the inferior border of the posterior lip of the cervix. (2) The subperitoneal space with the rectovaginal septum roughly 3-cm height (red arrow). The posterior wall of the vagina is in close relationship with the anterior rectal wall. (3) The perineal space with the rectovaginal triangle which contains adipose tissue (green arrow

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree