- The shoulder is very mobile and prone to dislocation

- Different patterns of injury in different age groups

- Plain radiographs remain the mainstay of imaging

- Anterior dislocations are obvious but posterior dislocations are subtle

- MRI, US, and CT are rarely necessary in the acute setting

Traumatic injury to the shoulder is a common presenting complaint to the emergency department. The shoulder girdle is highly mobile and it is particularly prone to dislocation (Box 4.1). There are different patterns of injury in different age groups. Plain radiographs are the initial investigation of choice for suspected fractures and dislocations. A variety of radiographic views of the shoulder may be obtained. The anatomy shown on each of these will be described. The radiological signs of pathology may be subtle so it is important to be familiar with the specific findings associated with certain injuries.

Three joints

- Glenohumeral

- Acromioclavicular

- Sternoclavicular

Three bones

- Scapula

- Humerus

- Clavicle

Anatomy

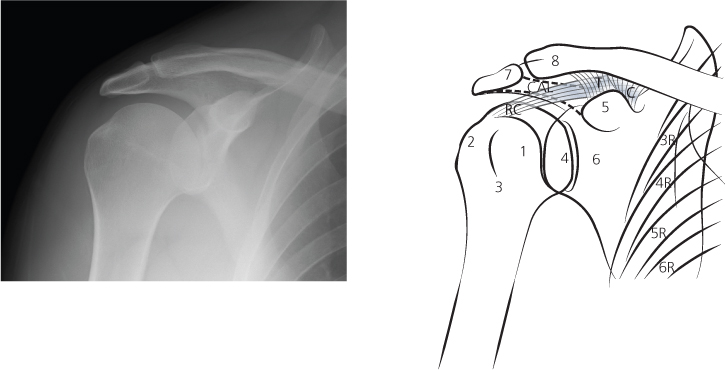

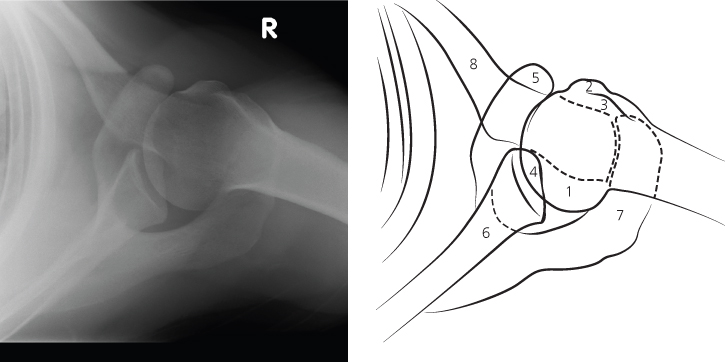

The shoulder girdle (Figures 4.1–4.3) is made up of three bones—the scapula, clavicle, and proximal humerus—and three joints—the glenohumeral (GHJ), acromioclavicular (ACJ) and sternoclavicular (SCJ) joints. The highly mobile GHJ is formed by the articular surfaces of the humeral head and the glenoid fossa. The glenoid cavity is deepened by a fibrocartilaginous ring—the glenoid labrum. The humeral head also includes the greater and lesser tuberosities, the sites of attachment of the rotator cuff tendons. The rotator cuff muscles and tendons are important dynamic stabilisers of the joint; the glenohumeral and coracohumeral ligaments also contribute to joint stability. The bicipital groove lies between the lesser and greater tuberosities and accommodates the long head of the biceps tendon. The ACJ is stabilised by ligaments around the joint itself as well as the strong coracoclavicular ligament, which anchors the clavicle to the scapula.

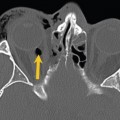

Figure 4.1 Normal AP right shoulder. 1, Humeral head; 2, greater tuberosity; 3, lesser tuberosity; 4, glenoid fossa; 5, coracoid process; 6, neck of scapula; 7, acromion; 8, lateral end of clavicle.

Figure 4.2 Normal axial shoulder. Note the coracoid process and acromion both project anteriorly. 1, Humeral head; 2, greater tuberosity; 3, lesser tuberosity; 4, glenoid fossa; 5, coracoid process; 6, neck of scapula; 7, acromion; 8, lateral end of clavicle.

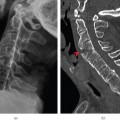

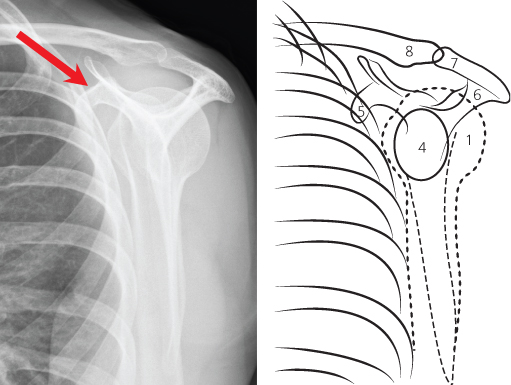

Figure 4.3 Normal Y view of shoulder. The coracoid process projects anteriorly and may be used as a landmark to determine the direction of humeral head dislocation. The glenoid fossa has been outlined.

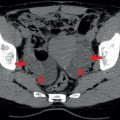

Important related neurovascular structures include the subclavian vessels and brachial plexus, which lie posterior to the clavicle, and the axillary neurovascular bundle passing inferior to the glenoid.

ABCs systematic assessment

- Adequacy—check correct views have been obtained

- Alignment—check joint spaces are the same

- Bone—trace the contours of all the bones

- Cartilage and joints—joint spaces should be uniform in width

- Soft tissues—change windows to look for soft tissue swelling and FB.

- Shoulder (GHJ)—AP and either a Y view or an axial view

- ACJ—AP and weight-bearing views

Adequacy

Two projections should always be performed. The AP view is routinely obtained and is the most useful for identifying pathology. There are three alternative second views. The axial view is taken with the arm abducted; this view will show dislocation clearly and is particularly useful for demonstrating small, avulsed fracture fragments. When it is painful to abduct the arm, the ‘Y’ view is a useful alternative, as it requires no shoulder movement. A less commonly used second view is the axial oblique; this also requires no shoulder movement and demonstrates the relation of the humeral head to the glenoid clearly. The AP view shows the ACJ well but an additional weight-bearing view may be requested if subluxation or dislocation is suspected.

Alignment

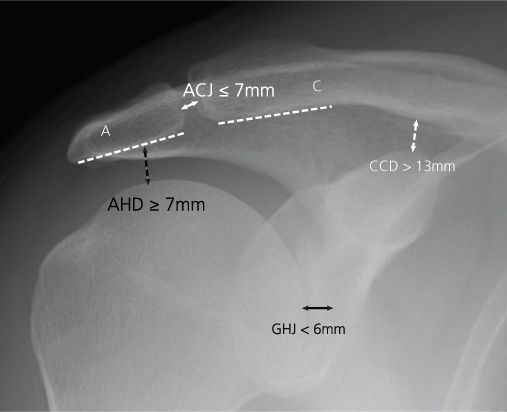

Box 4.2 shows alignment and normal measurements.

- GHJ space less than 6 mm

- Inferior margin of the clavicle and acromion should be level

- ACJ should be no greater than 7 mm

- Coracoclavicular distance no greater than 13 mm

- AHD of <7 mm is highly suggestive of a large rotator cuff tear

Figure 4.4 Normal measurements in the shoulder.

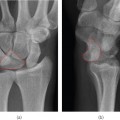

Assess the GHJ alignment on the AP view by checking there is an even joint space between the humeral head and glenoid. There should be an equal distance between the margins of their articular surfaces. The normal GHJ space is no greater than 6 mm. The axial view shows the humeral head normally aligned with the glenoid fossa like ‘a golf ball sitting on a tee’. On the ‘Y’ view check that the humeral head is positioned over the junction of the ‘Y’ shape, which indicates the position of the glenoid fossa.

The ACJ alignment is assessed on the AP view. The inferior margins of the acromion and lateral clavicle should be level with each other. This rule holds true in most instances but due to normal variation between individuals there is slight misalignment at this inferior margin in up to 20%. ACJ injury may result in widening of the joint space (normally no greater than 7 mm) or the coracoclavicular distance (normally no greater than 13 mm).

Check the space between the superior margin of the humeral head and the undersurface of the acromion. This acromiohumeral space accommodates part of the rotator cuff and if it is narrowed to less than 7 mm, it indicates the presence of a large rotator cuff tear.

Bone

The contour of each bone should be carefully assessed to ensure it is smooth. Check there is no step or buckle of the cortex that may indicate a fracture. Other subtle signs of a fracture include disruption of the trabecular pattern and linear sclerosis that may indicate impaction. Each view needs to be systematically evaluated. The AP and axial views are particularly useful for identifying small fracture fragments. Anterior dislocation is commonly associated with a Hill–Sachs fracture in the posterosuperior humeral head and/or a Bankart fracture of the anteroinferior bony glenoid. Ribs shown on the AP view also need to be checked to exclude a fracture.

Cartilage and joints

Ensure the joint spaces are preserved. The borders of the humeral head and glenoid should appear as two parallel lines. The GHJ space may appear reduced for technical reasons as well as true cartilage loss. Where there is true cartilage loss, there may be secondary findings including subarticular sclerosis and osteophytes. As primary degeneration of the GHJ is uncommon, cartilage loss due to another condition such as rheumatoid arthritis, haemophilia or, rarely, infection should be considered.

Soft tissues

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree