7

Small Bowel

Small Bowel Obstruction

Overview

Most commonly due to adhesions (70%) or incarceration of bowel within a hernia

Most commonly due to adhesions (70%) or incarceration of bowel within a hernia

Other etiologies include small bowel tumor, volvulus, intussusception, and strictures

Other etiologies include small bowel tumor, volvulus, intussusception, and strictures

Obstruction may be partial or complete

Obstruction may be partial or complete

Signs and Symptoms

Colicky periumbilical pain that may be relieved with bilious emesis

Colicky periumbilical pain that may be relieved with bilious emesis

Abdominal distention, tenderness, and occasional high-pitched bowel sounds

Abdominal distention, tenderness, and occasional high-pitched bowel sounds

Severe tenderness at the site of incarcerated hernia with possible overlying skin changes

Severe tenderness at the site of incarcerated hernia with possible overlying skin changes

Patients with complete bowel obstruction will have absence of flatus or bowel movement, patients with partial bowel obstruction will present with abdominal distention with decreased passage of flatus

Patients with complete bowel obstruction will have absence of flatus or bowel movement, patients with partial bowel obstruction will present with abdominal distention with decreased passage of flatus

Diagnosis

Abdominal x-rays will show multiple air–fluid levels with distended loops of small bowel

Abdominal x-rays will show multiple air–fluid levels with distended loops of small bowel

CT scan with IV contrast may be obtained to assess for a transition point

CT scan with IV contrast may be obtained to assess for a transition point

Treatment/Management

NPO for bowel rest, IV fluids, NG decompression; correct any underlying electrolyte abnormalities

NPO for bowel rest, IV fluids, NG decompression; correct any underlying electrolyte abnormalities

Attempt to perform bedside reduction of any incarcerated hernia

Attempt to perform bedside reduction of any incarcerated hernia

Patients with diffuse peritonitis or complete bowel obstruction should warrant surgical exploration

Patients with diffuse peritonitis or complete bowel obstruction should warrant surgical exploration

Patients with partial bowel obstruction who do not improve with conservative management will require exploration and adhesiolysis with possible bowel resection

Patients with partial bowel obstruction who do not improve with conservative management will require exploration and adhesiolysis with possible bowel resection

Patients without signs of incarcerated hernia and who have no previous abdominal surgeries should also be surgically explored

Patients without signs of incarcerated hernia and who have no previous abdominal surgeries should also be surgically explored

RADIOLOGY

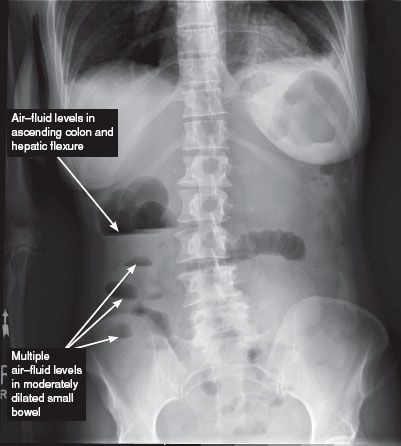

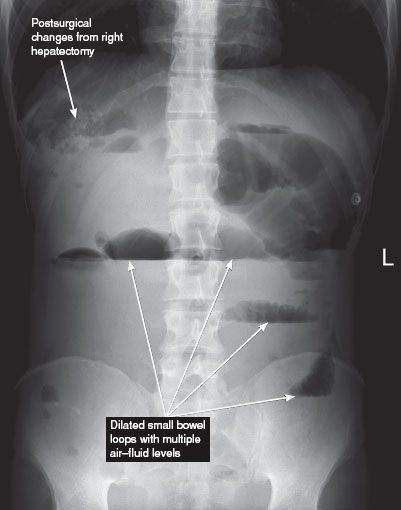

Plain film findings (Fig. 7.1)

Plain film findings (Fig. 7.1)

• Dilated small bowel loops with air fluid levels

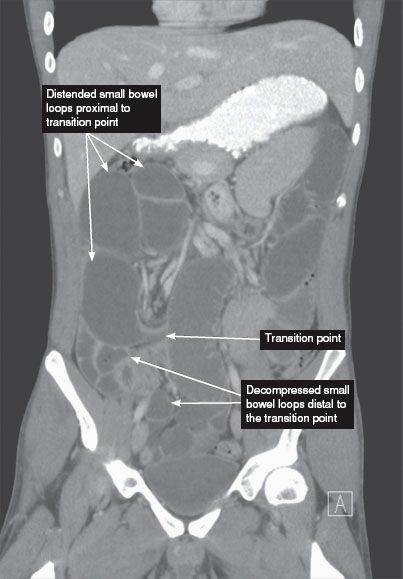

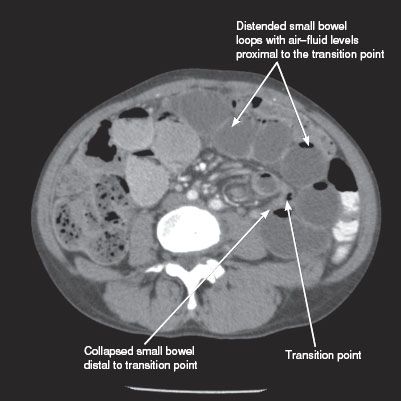

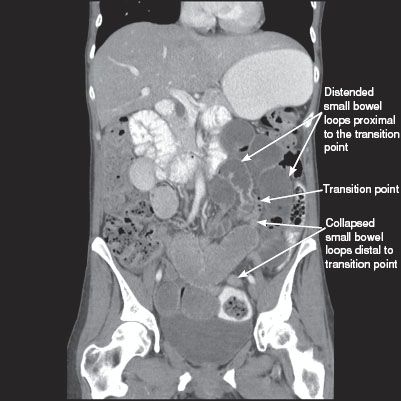

CT findings (Fig. 7.1)

CT findings (Fig. 7.1)

• Fluid-filled, dilated small bowel loops

• Closed-loop obstruction manifests as a C-shaped configuration of dilated bowel loops with mesenteric vessels converging toward the point of torsion

• Strangulation is characterized by bowel wall thickening, little or no contrast enhancement of the bowel wall, engorgement of mesenteric vasculature, and mesenteric edema

• Small bowel loops are dilated proximal to the obstruction, and decompressed distal to the obstruction

FIGURE 7.1 A–H

FIGURE 7.1 A

FIGURE 7.1 B

FIGURE 7.1 C

FIGURE 7.1 D

FIGURE 7.1 E

FIGURE 7.1 F

FIGURE 7.1 G

FIGURE 7.1 H

Ileus

Overview

Lack of peristalsis or bowel function without a structural obstruction

Lack of peristalsis or bowel function without a structural obstruction

Most commonly secondary to abdominal surgery

Most commonly secondary to abdominal surgery

Other causes are electrolyte abnormalities, intra-abdominal abscess, systemic infection, hypothyroidism, or other medications such as anticholinergics

Other causes are electrolyte abnormalities, intra-abdominal abscess, systemic infection, hypothyroidism, or other medications such as anticholinergics

Signs and Symptoms

Abdominal distension without flatus or bowel movements

Abdominal distension without flatus or bowel movements

Bilious or feculent emesis

Bilious or feculent emesis

Generalized abdominal distension associated with discomfort without diffuse peritonitis

Generalized abdominal distension associated with discomfort without diffuse peritonitis

Diagnosis

Same as small bowel obstruction

Same as small bowel obstruction

Treatment/Management

Same as small bowel obstruction

Same as small bowel obstruction

May consider initiation of total parenteral nutrition (TPN) for patients who have prolonged ileus with underlying malnutrition

May consider initiation of total parenteral nutrition (TPN) for patients who have prolonged ileus with underlying malnutrition

RADIOLOGY

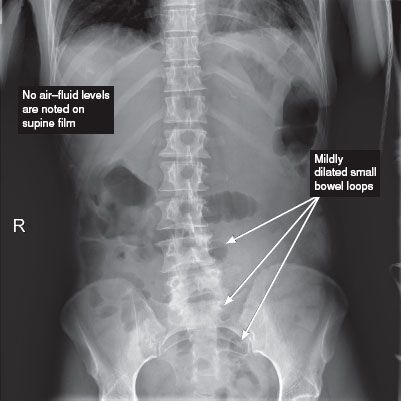

Plain film findings (Fig. 7.2)

Plain film findings (Fig. 7.2)

• Distended small bowel loops with air fluid levels

• May be indistinguishable from SBO

• Distal air in the rectum may help differentiate ileus from SBO

FIGURE 7.2 A,B

FIGURE 7.2 A

FIGURE 7.2 B

Small Bowel Enterocutaneous Fistula

Overview

A fistula is defined as an abnormal connection between two epithelized organs

A fistula is defined as an abnormal connection between two epithelized organs

Small bowel enterocutaneous fistula is usually caused by unrecognized iatrogenic injury to the bowel, anastomotic leak, inflammatory bowel disease, or malignancy

Small bowel enterocutaneous fistula is usually caused by unrecognized iatrogenic injury to the bowel, anastomotic leak, inflammatory bowel disease, or malignancy

Signs and Symptoms

Fever, leukocytosis, ileus, abdominal tenderness followed by drainage of enteric contents via the wound or skin

Fever, leukocytosis, ileus, abdominal tenderness followed by drainage of enteric contents via the wound or skin

Factors that prevent fistula closure—(FRIEND)

Factors that prevent fistula closure—(FRIEND)

• Foreign body

• Radiation

• Inflammation/infection

• Epithelialization of the tract

• Neoplasm

• Distal obstruction

Diagnosis

CT scan with enteric contrast will help identify any undrained abscess. It might help identify the origin of the fistula

CT scan with enteric contrast will help identify any undrained abscess. It might help identify the origin of the fistula

Fistulogram or sinogram consists of contrast injection into the cutaneous end of the fistula to evaluate the tract and origin of the fistula

Fistulogram or sinogram consists of contrast injection into the cutaneous end of the fistula to evaluate the tract and origin of the fistula

Treatment/Management

Usually treatment consists of making patient NPO, parenteral nutrition, possible octreotide to decrease the output from the fistula for easier wound management

Usually treatment consists of making patient NPO, parenteral nutrition, possible octreotide to decrease the output from the fistula for easier wound management

Definitive treatment is surgery if spontaneous closure does not occur within 4 to 5 weeks’ time

Definitive treatment is surgery if spontaneous closure does not occur within 4 to 5 weeks’ time

RADIOLOGY

Plain film findings

Plain film findings

• Contrast injection through the fistula can diagnose the tract between the skin and the small bowel lumen

CT findings (Fig. 7.3)

CT findings (Fig. 7.3)

• CT can be performed in addition to a fistulogram to distinguish fluid collections from bowel loops, and also to guide percutaneous drainage of any abscesses

• A fistula between the small bowel and skin can sometimes be directly seen on CT

• Fat stranding and abscess formation may be seen around the fistula tract

FIGURE 7.3 A–C

A. Stomach

B. Descending colon

C. Portal vein

D. Liver

E. Mesenteric vessels

F. Psoas muscle

G. IVC

H. Common iliac artery

I. Small bowel loops

J. Vertebra

K. Kidney

FIGURE 7.3 A

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree