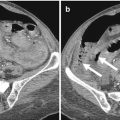

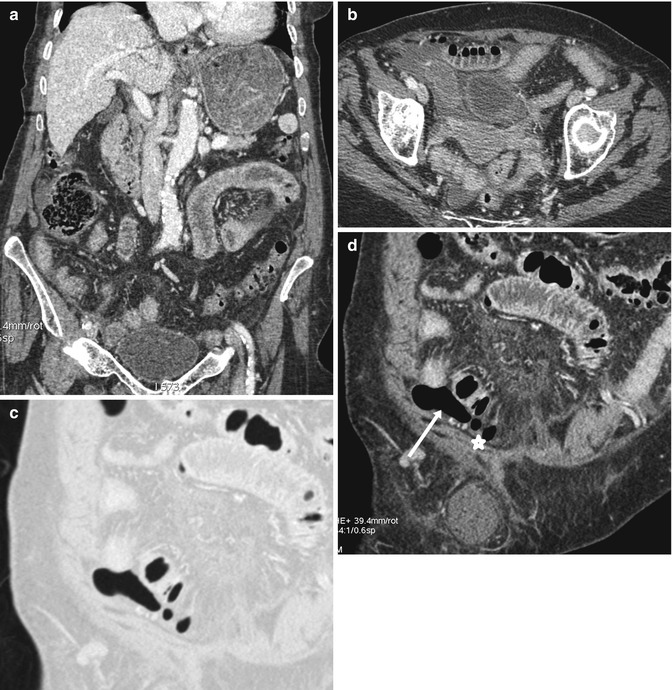

Fig. 6.1

A 38-year-old patient with acute abdomen from ileal perforation. CT examination shows the presence of free peritoneal air with falciform ligament sign (a, b) and some small peritoneal bubble gas; multiplanar reconstructions seem to show the evidence of bowel discontinuity at level of the left colonic flexure (c, arrow in d); however, surgery revealed the presence of an ileal perforation. Small amount of peritoneal fluid and presence of free peritoneal air in the abdomen can be appreciated (e, f); note some bubbles of gas in the soft tissue of the right abdominal wall (small arrow in g). Small intestinal loops of jejunum and proximal ileum are collapsed, whereas in the pelvis, free peritoneal air (longer arrow in g) surrounds an ileal loop distended by fluid with signs of endoluminal stasis (f)

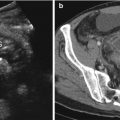

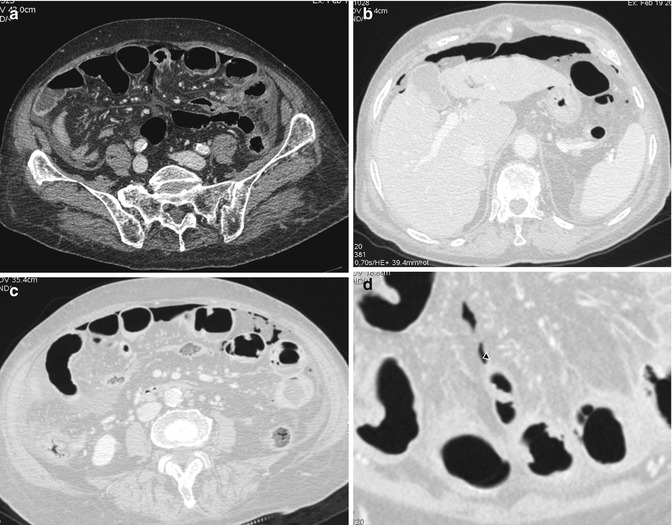

Fig. 6.2

A 90-year-old patient with acute abdomen due to perforation from small bowel complicated obstruction. CT shows the presence of small amount of free peritoneal fluid (a, b), fluid distension of the stomach, moderate distension of some small intestinal loops at the left abdominal quadrant with parietal thickening (a). Note the evidence of bowel segment distended by fluid and with decreased enhancement in the right iliac fossa (b). The presence of small amount of free air surrounding a bowel loop in the right iliac fossa is evident (c, arrow and star in d)

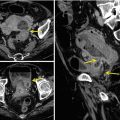

Fig. 6.3

An 88-year-old patient with perforation from small bowel obstruction. CT shows the presence of free peritoneal air (a–d), small amount of free fluid, small bowel proximal loops moderately distended, some of them characterized by altered trophism. Multiplanar reformation shows the presence of linear mesenteric gas surrounding a small intestinal loop in the left abdominal quadrant suggestive of fissuration (arrowhead in d)

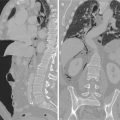

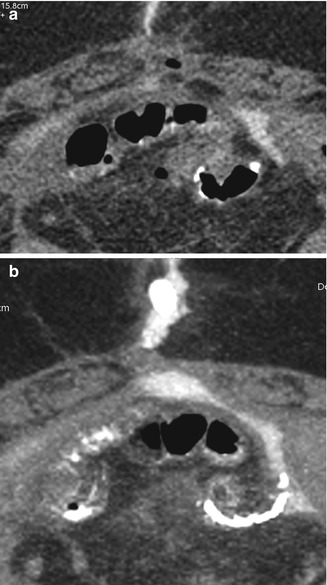

Fig. 6.4

A 56-year-old patient with anastomotic leaks well documented by the endoluminal positive contrast medium (a, b)

6.3 Considerations

The etiology of small intestine perforations seems to influence the diagnostic performance also in CT examinations: in blunt small bowel perforation, discontinuity of the bowel wall and extraluminal gas has been reported, respectively, on 19.2 and 74.4 % of examinations [11], attesting a CT diagnosis as highly specific but not sensitive [11].

Inflammatory conditions of the small intestines could be considered in evaluating CT examinations of patients with acute abdomen and suspected hollow viscus perforations. Crohn’s disease and other inflammatory conditions and complications with presence of abscesses must be accurately noted in location and distribution. A rare condition causing perforations almost localized and covered is represented by the small bowel diverticulitis [12], in which wall thickening of the small bowel loop and an adjacent inflammatory mass containing air bubbles [12] could be noted. Small bowel diverticula are rare and mostly asymptomatic [12], but they become clinically relevant when complications arise, such as diverticulitis [12]. The symptoms of jejunoileal diverticulitis are nonspecific, and the diagnosis is performed mainly by imaging studies [12], especially CT. Small bowel diverticulitis at CT usually presents as a focal inflammatory lesion, and the differential diagnosis includes perforated neoplasm, foreign body perforation, small bowel ulceration from nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, Crohn’s disease, and diverticulitis [13, 14].

Different and various processes may cause acute peritonitis from perforations: on CT, in addition to the small bowel findings, there is some combination of free intraperitoneal gas or fluid, mesenteric edema, and peritoneal thickening [15]. In the presence of focal perforation of the gastrointestinal tract, the specific site of perforation seems to be identifiable on CT in 85–90 % of cases [11, 16]. Moreover, in addition to directly visualizing the site of perforation, associated CT findings to look for include a cluster of extraluminal gas bubbles close to the suggestive perforation site as well as an abscess formation [11, 16] especially in covered perforations. In patients affected by severe disease and poorer outcome from intestinal perforations, the attenuation of the peritoneum on non-contrast CT has been reported as significantly lower, presumably reflecting a greater degree of edema [17]. The specific air distribution seems to be more frequently present in patients with gastroduodenal perforations than lower gastrointestinal tract perforations [18]; however, the specific air distribution had a less significant role than the strong predictors of the site of bowel perforation [18]. Periportal free air sign has been reported as a useful finding that can help to distinguish upper from lower gastrointestinal tract perforation: when this sign is present, upper gastrointestinal tract perforation is strongly suggested [19]. However, the specific air distribution could be also influenced by the perforation site, the elapsed time after perforation, and the amount of pneumoperitoneum [18]. Therefore, prediction of the perforation site using specific free air distributions could be considered as limited [18].

A correctly performed CT examination represents the basic condition for an efficient diagnosis. Administration of intravenous contrast medium could be considered important for all the acute intestinal conditions in order to evaluate the bowel wall feature and enhancement, essential and useful for all differential diagnoses. In suspected gastrointestinal perforations, the incremental diagnostic value of low-thickened around or less than 1 mm slice reconstructions for direct visualization of the perforation site in patients with nontraumatic free pneumoperitoneum has been already assessed [10] as well as the agreement between readers as significantly higher with thin slices and reformatting [10]. Regarding the CT features related to small bowel perforation, the presence of extraluminal air is the first finding to search for, from the CT-falciform ligament sign crossing the midline to scattered pockets of air [20]. Small bowel wall thickening (>3 mm) [20], either segmental or diffuse, could represent the second important finding to note for. All the eventual associated signs such as intestinal fluid or gas distension or collapsed loops, abscess formation, peritoneal, fat stranding evidence [20], they have to be considered as puzzle pieces in order to make a suggestive diagnostic frame (Fig. 6.1). With respect to conventional plain film, CT is able to detect extraluminal air in more cases and could actually represent a good imaging tool to differentiate the various types of gastrointestinal perforations [20]. Among not frequent causes of pneumoperitoneum, there are also the ingested foreign bodies such as generally unconsciously ingested chicken and fish bones [21]. From a clinical point of view, the acute presentations of this intestinal damage are nonspecific, mimicking more common acute abdominal conditions [21]: at CT thickened intestinal segment with localized pneumoperitoneum, surrounded by fatty infiltration and associated with already present or developing obstruction or sub-obstruction, could represent the most common CT signs; however, the specific diagnosis could be done by the identification of the foreign bodies [21]. The high specificity of the CT diagnosis in making avoidance of surgical exploration possible has been reported not only in the latter case of perforations just reported [21] but also in evaluating postoperative acute abdominal conditions such as post-laparoscopic interventional procedures [22]. In case of evaluation of patients who underwent laparoscopic procedures more frequently such as cholecystectomies, the eventual intestinal perforation due to trocar injury leads to extensive pneumoperitoneum [22]. In fact, small bowel injuries should be suspected when at CT examination a large or an increasing amount of free air is detected following laparoscopic procedures [22].

CT diagnosis of perforation is essentially based on direct findings of extraluminal air or positive oral contrast medium, as well as on indirect findings of an abscess or an inflammatory mass or a bowel wall-related phlegmon or abscess with fluid in the mesentery or surrounding a radiopaque foreign body [23]. The CT sensitivity in intestinal perforations in the emergency setting is high; however, further evaluations by the use of endoluminal positive contrast medium could be required to demonstrate the site and nature of the perforation [2], especially in postoperative intestine to evaluate any eventual anastomotic leaks (Fig. 6.4).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree