, Joungho Han2, Man Pyo Chung3 and Yeon Joo Jeong4

(1)

Department of Radiology Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

(2)

Department of Pathology Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

(3)

Department of Medicine Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

(4)

Department of Radiology, Pusan National University Hospital, Busan, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

Abstract

Small nodules, usually less than 10 mm in diameter, are regarded to be centrilobular when the nodules are separated from pleural surfaces or the interlobular septa by a distance of several millimeters, usually centered 4–10 mm from the pleural or fissural surfaces or from interlobular septa [1, 2]. They are frequently associated with centrilobular branching nodular structures, thus forming the so-called tree-in-bud sign (Figs. 18.1 and 18.2) (see also Chap. 9). The small nodules represent lesions involving the small airways. However, vascular lesions involving the arterioles and capillaries may simulate the centrilobular small nodules and branching nodular structures (vascular tree-in-bud sign) [1, 3, 4] (Fig. 18.3).

Small Nodules with Centrilobular Distribution

Definition

Small nodules, usually less than 10 mm in diameter, are regarded to be centrilobular when the nodules are separated from pleural surfaces or the interlobular septa by a distance of several millimeters, usually centered 4–10 mm from the pleural or fissural surfaces or from interlobular septa [1, 2]. They are frequently associated with centrilobular branching nodular structures, thus forming the so-called tree-in-bud sign (Figs. 18.1 and 18.2) (see also Chap. 9). The small nodules represent lesions involving the small airways. However, vascular lesions involving the arterioles and capillaries may simulate the centrilobular small nodules and branching nodular structures (vascular tree-in-bud sign) [1, 3, 4] (Fig. 18.3).

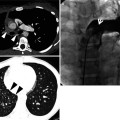

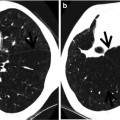

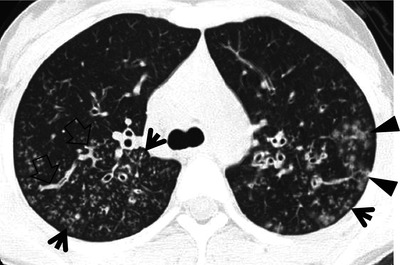

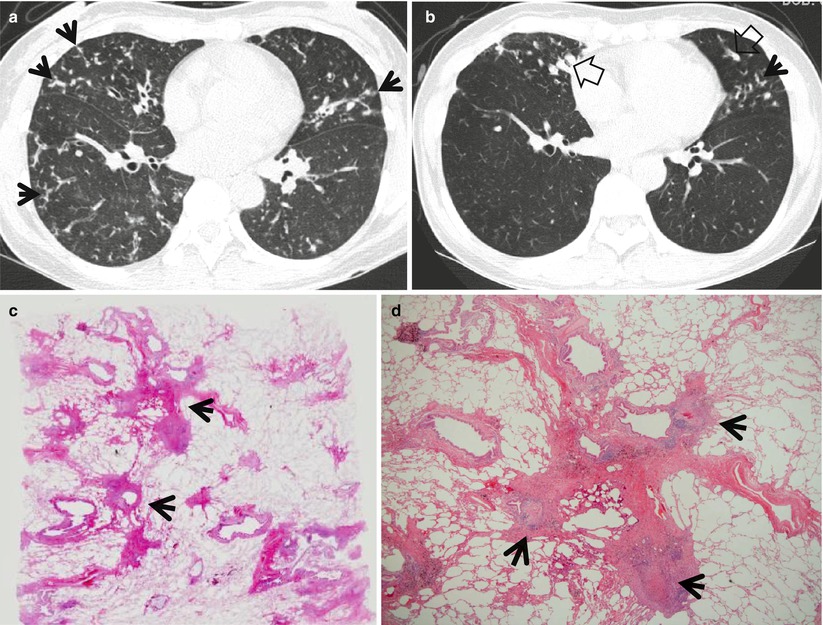

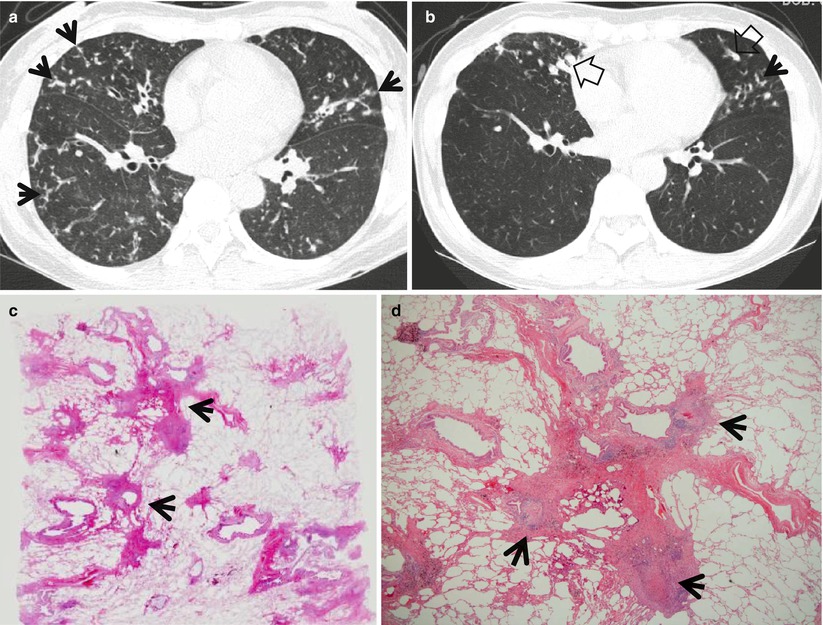

Fig. 18.1

Cystic fibrosis in a 21-year-old woman. Lung window image of CT scan (2.5-mm section thickness) obtained at level of azygos arch shows well-defined (arrows) and poorly defined (arrowheads) tree-in-bud sign in both upper lobes. Also note mucus plugging (open arrows) in medium-sized airways

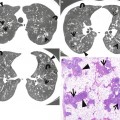

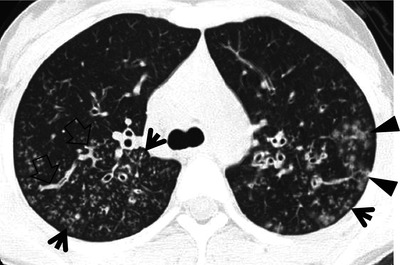

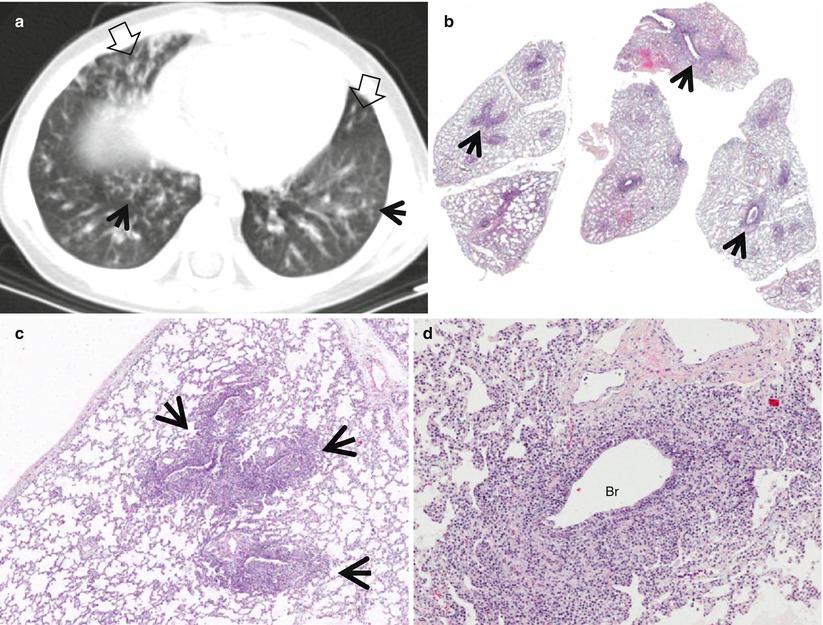

Fig. 18.2

Infectious bronchiolitis showing tree-in-bud signs in a 3-year-old boy. (a) Lung window image of CT scan (5.0-mm section thickness) obtained at level of liver dome shows tree-in-bud signs (arrows) in both lower lobes. Also note bronchiectasis (open arrows) in bottom of right middle lobe and lingular division of left upper lobe. (b) Low-magnification (×10) photomicrograph of surgical biopsy specimen obtained from right lower lobe demonstrates bronchiolocentric (arrows) dense inflammatory cell (cellular) infiltration. (c) High-magnification (×100) photomicrography exhibits more clearly bronchiolocentric (arrows) dense inflammatory cell infiltration. (d) High-magnification (×200) photomicrograph discloses thickened bronchiolar wall with dense lymphoplasma cell infiltration and expansion of subepithelial connective tissue. Br bronchiole

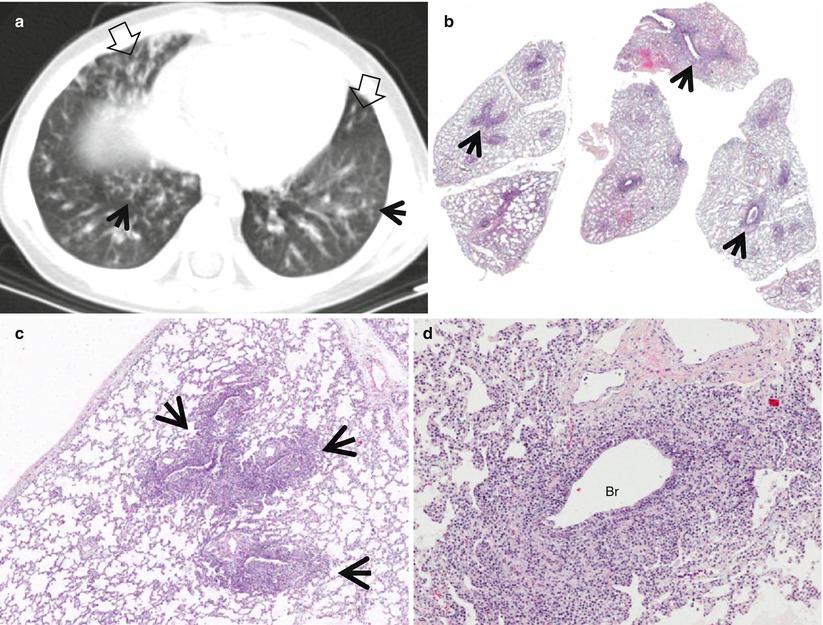

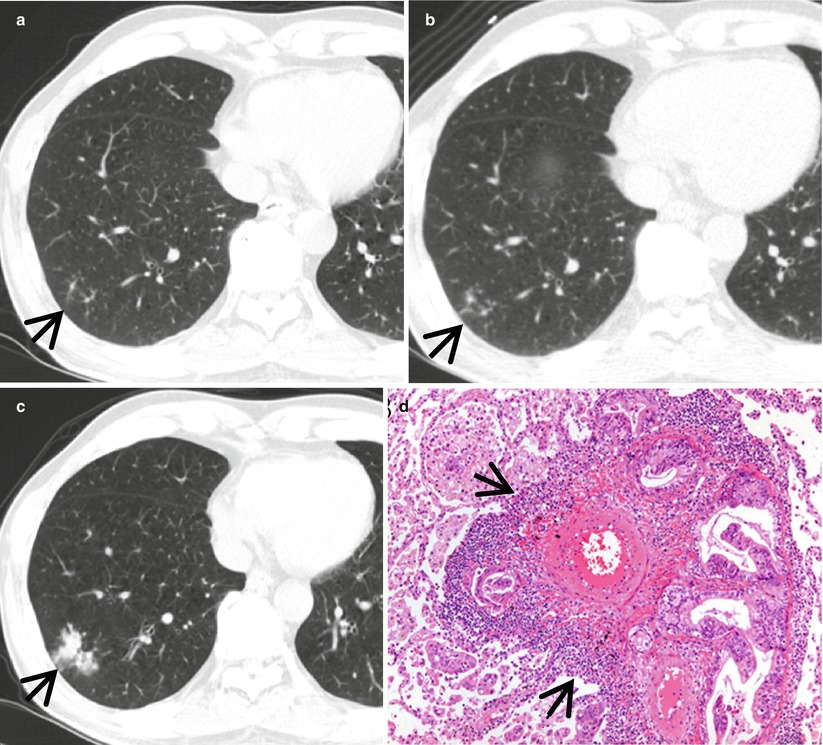

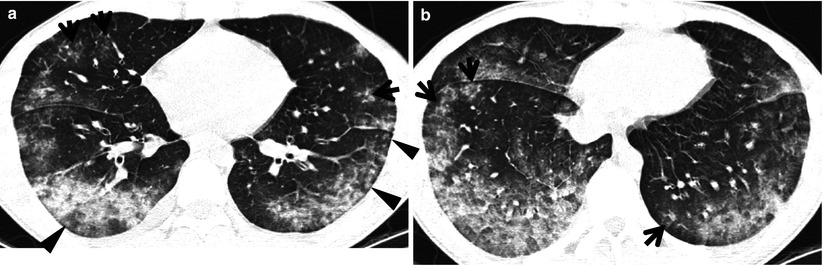

Fig. 18.3

Lymphangitic metastasis along bronchovascular bundles manifesting as vascular tree-in-bud sign in a 59-year-old man who has pancreas head cancer. (a–c) Lung window images of serial CT scans obtained at same level over the follow-up period of 6 months show evolving lung lesion from tree-in-bud sign (arrows in a and b) to localized area of lobular consolidation or a poorly defined nodule (arrow in c) in the right lower lobe. (d) High-magnification photomicrograph of surgical lung biopsy obtained from right lower lobe and at similar time to (c) discloses tumor cells (arrows) tracking arteriolar walls (definition-wise, lymphangitic tumor spread). Please note patent arteriolar lumen without cancer cells

Diseases Causing the Pattern

The diseases manifesting small nodules of centrilobular distribution or tree-in-bud signs include infectious bronchiolitis including Haemophilus influenzae pneumonia and Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia [5] (Fig. 18.4), bronchogenic dissemination of pulmonary tuberculosis [6, 7] or the nodular bronchiectatic form of nontuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) pulmonary disease [8, 9] (Fig. 18.5), diffuse panbronchiolitis (DPB) [10] (Fig. 18.6), subacute hypersensitivity pneumonitis, follicular bronchiolitis [11] (Fig. 18.7) or bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma [12], and cystic fibrosis [13].

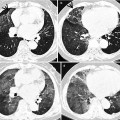

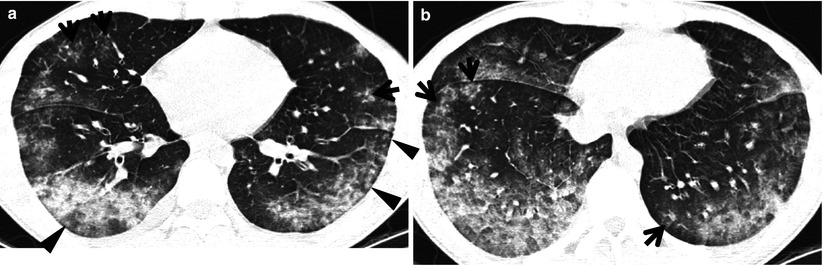

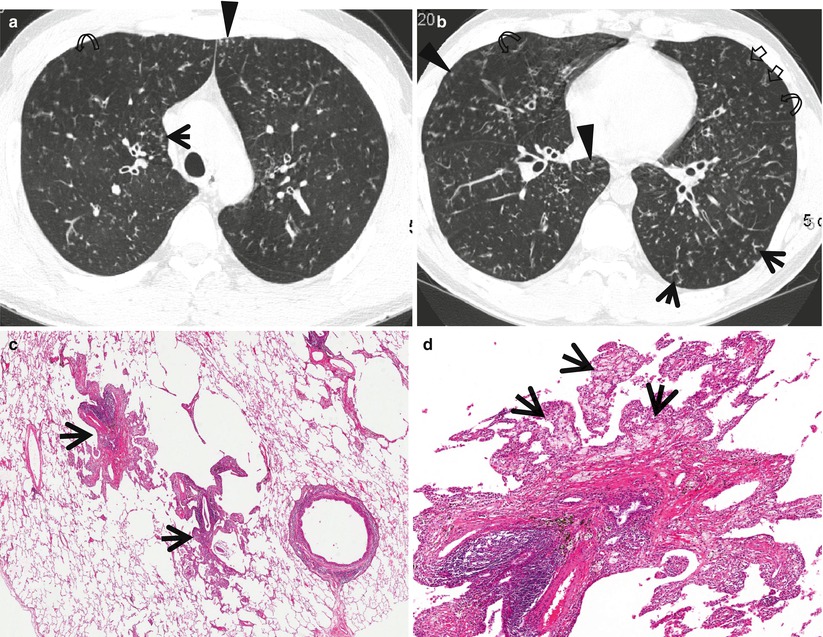

Fig. 18.4

Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in a 2-year-old man. (a, b) Lung window images of CT scans (2.5-mm section thickness) obtained at levels of cardiac ventricle (a) and suprahepatic inferior vena cava (b), respectively, show extensive ground-glass opacity in both lungs. Also note poorly formed centrilobular small nodules (arrowheads) and tree-in-bud signs (arrows) in both lungs

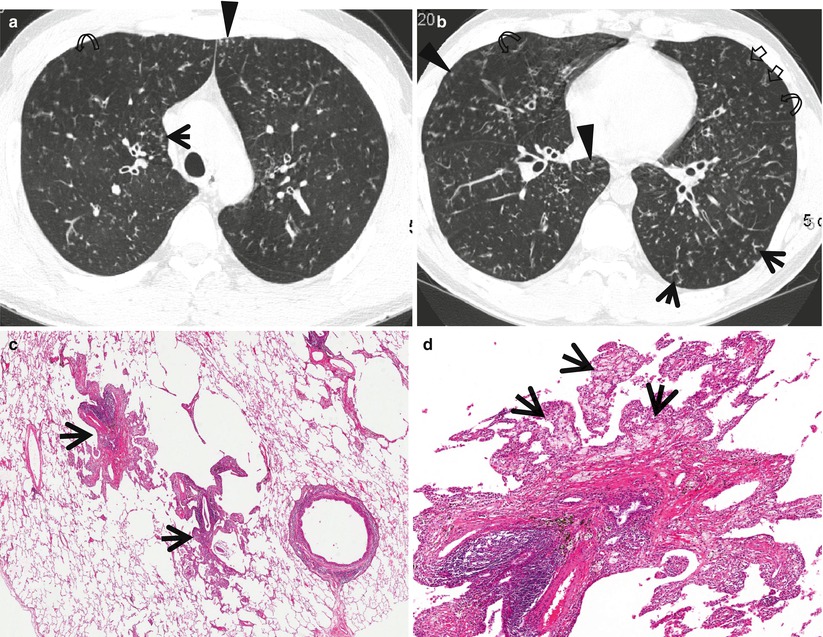

Fig. 18.5

Mycobacterium intracellulare pulmonary disease in a 53-year-old woman. (a, b) Lung window images of consecutive CT scans (2.5-mm section thickness) obtained at level of inferior pulmonary veins show tree-in-bud signs (arrows) in both lungs. Also note bronchiectasis with (open arrows) or without mucus plugging especially in right middle lobe and lingular division of left upper lobe. (c) Low-magnification photomicrograph (×40) of pathologic specimen obtained from a different patient with nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease exhibits bronchiolocentric (membranous bronchiole, arrows) chronic inflammation, fibrosis, and granuloma formation. (d) High-magnification photomicrograph (×100) discloses granulomas (arrows) with surrounding chronic inflammation and fibrosis along membranous bronchioles

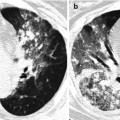

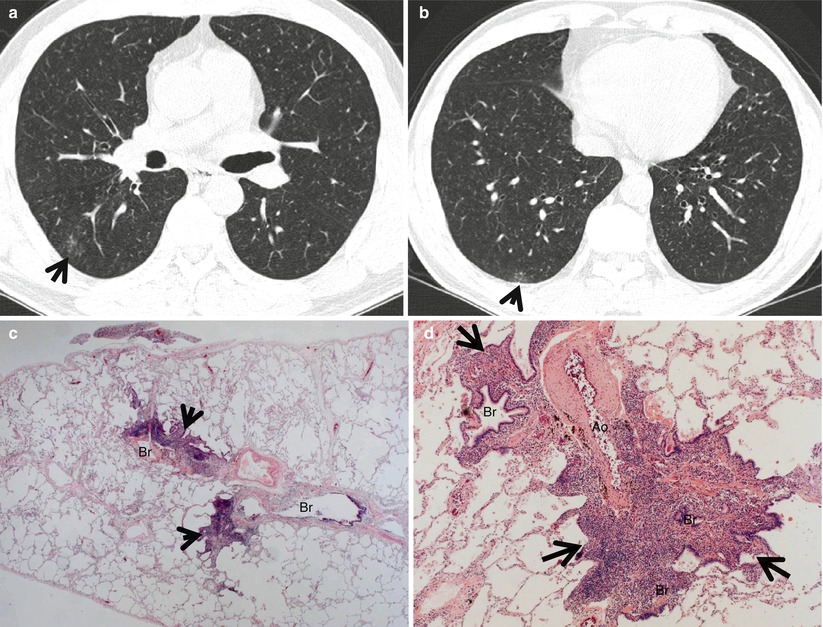

Fig. 18.6

Diffuse panbronchiolitis in a 38-year-old man. (a, b) Lung window images of thin-section CT scans (1.5-mm section thickness) obtained at levels of aortic arch (a) and right inferior pulmonary vein (b), respectively, show small centrilobular nodules (arrowheads), tree-in-bud signs (arrows), bronchiolectasis (open arrows), and area of mosaic attenuation (curved arrows) in both lungs. (c) Low-magnification (×40) photomicrograph of surgical lung biopsy obtained from right lower lobe demonstrates marked membranous bronchiolar wall thickening (arrows) with lymphocytes and macrophages. (d) A more closer look (×100) of the inflamed bronchiole discloses bronchiolar wall thickening with chronic inflammatory cell infiltration and patchy aggregates of fibrosis. Surrounding alveolar walls contain many foamy macrophages (arrows)

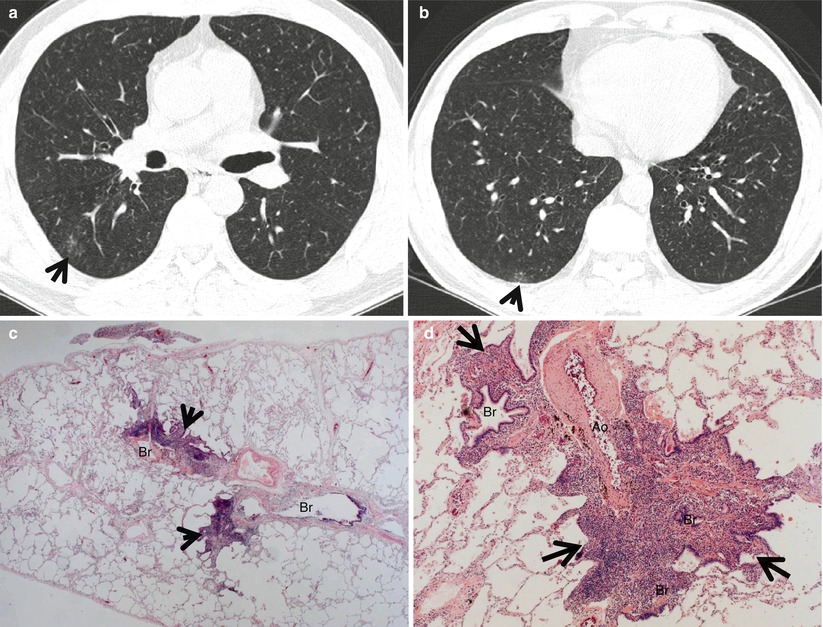

Fig. 18.7

Follicular bronchiolitis in a 61-year-old man with Sjögren’s syndrome. (a, b) Lung window images of thin-section CT scans (1.5-mm section thickness) obtained at levels of aortic arch (a) and right inferior pulmonary vein (b), respectively, show small centrilobular nodules and branching nodular structures (tree-in-bud signs, arrows) in superior and posterior basal segments of right lower lobe. (c) Low-magnification (×40) photomicrograph of surgical biopsy specimen obtained from right lower lobe demonstrates bronchiolocentric (Br) inflammatory lesions (arrows). (d) High-magnification (×200) photomicrograph discloses narrowed or obliterated bronchiolar lumen (Br) owing to dense lymphocyte infiltrates (arrows). Ao arteriole

Vascular tree-in-bud sign may be seen in pulmonary tumor embolism [3] or localized lymphangitic carcinomatosis (Figs. 18.3 and 18.8), foreign-body-induced necrotizing vasculitis or necrotizing pulmonary vasculitis in systemic lupus erythematosus [4, 6], and localized pulmonary lymphatic metastasis [14].

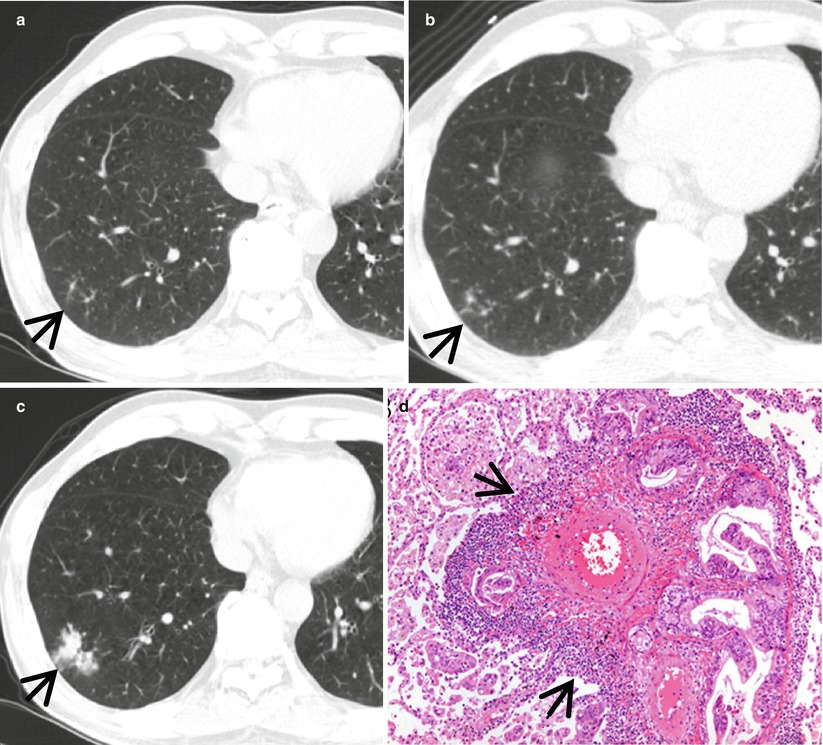

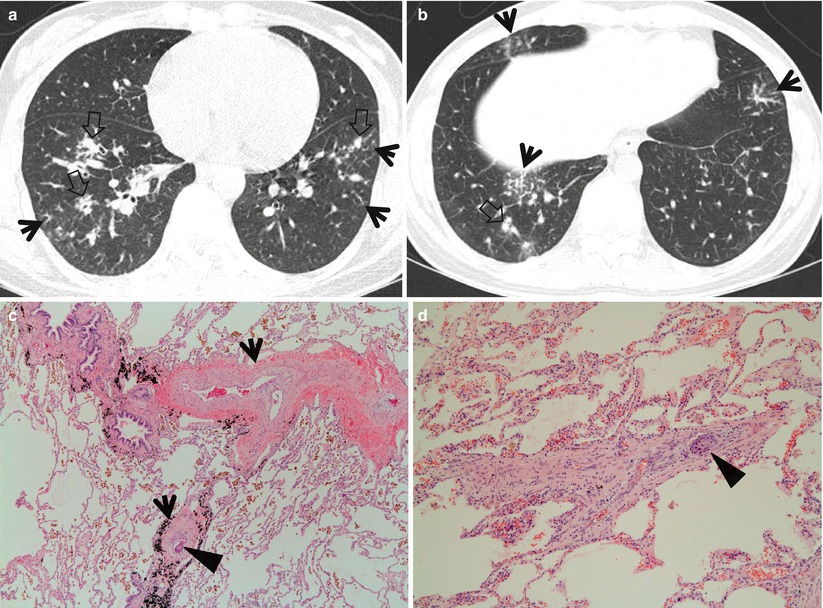

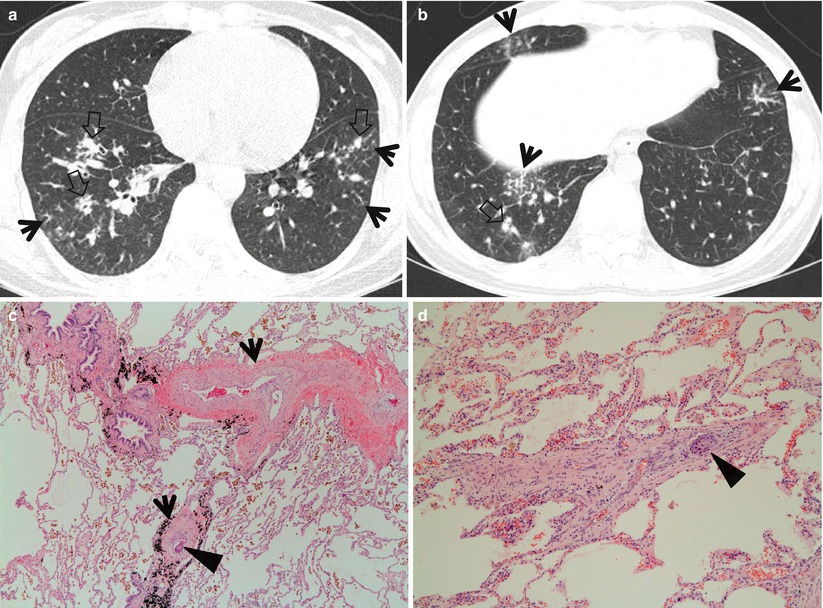

Fig. 18.8

Tumor emboli and lymphangitic carcinomatosis along bronchovascular bundles showing vascular tree-in-bud signs in a 34-year-old woman with gastric cancer. (a, b) Lung window images of thin-section CT scans (1.5-mm section thickness) obtained at levels of cardiac ventricle (a) and liver dome (b), respectively, show thickened axial interstitium (bronchovascular bundles) (open arrows) and several foci of tree-in-bud signs (arrows) in both lungs. (c) High-magnification (×100) photomicrograph of surgical lung biopsy specimen from another patient demonstrates dilated arterioles (arrows) with thickened wall. Please note intravascular tumor emboli (arrowhead). There are many hemosiderin-laden macrophages in alveolar spaces. (d) Another photomicrograph (×100) discloses an arteriole with thick wall containing intraluminal tumor emboli (arrowhead)

Distribution

In infectious bronchiolitis and DPB, the small nodules or tree-in-bud signs show middle and lower lung zone predominance. In particular, the small nodules in DPB depict symmetric and subpleural distribution along with bronchiectasis [10]. They are random and patchy in distribution in bronchogenic dissemination of tuberculosis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and follicular bronchiolitis or bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma or follicular bronchiolitis. Right middle lobe and lingular division of the left upper lobe are typical location of nodular bronchiectatic form of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease. Other lobes such as right upper lobe and both lower lobes may have lesions of tree-in-bud signs (pathologic cellular bronchiolitis). The lesions of bronchiectasis and cellular bronchiolitis (tree-in-bud signs) in the disease are asymmetrically distributed, differently from DPB [8, 9].

In tumor thrombotic microangiopathy, necrotizing vasculitis, and localized lymphatic metastasis, the vascular tree-in-bud sings demonstrate lower lung zone and subpleural predominance.

Clinical Considerations

Chronic maxillary sinusitis is usually associated with DPB. Follicular bronchiolitis is a kind of lymphoproliferative disease. Therefore, the disease is frequently associated with rheumatoid arthritis, mixed collagen vascular disorders, autoimmune disorders, or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [11]. Patient diagnosis of cystic fibrosis may be confirmed with positive chloride sweat test in all cases. As in DPB, maxillary sinusitis is frequently associated and the sinusitis may be used as a surrogate model for gene therapy [15].

Pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy is infrequently seen in a patient with gastric cancer [16], ovarian cancer, or lung invasive adenocarcinoma. In tumor thrombotic microangiopathy, hypoxemia is severe and patient complains of progressive dyspnea.

Key Points for Differential Diagnosis

Diseases | Distribution | Clinical presentations | Others | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Zones | ||||||||||||

U | M | L | SP | C | R | BV | R | Acute | Subacute | Chronic | ||

Infectious bronchiolitis | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

Bronchogenic dissemination of TB | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | With or without parenchymal opacity (TB) | ||||

NTM disease | + | + | + | + | + | With bronchiectasis, mainly in RML and Li division of LUL | ||||||

DPB | + | + | + | + | + | Sinusitis, bilateral symmetric distribution with bronchiectasis | ||||||

HP | + | + | + | + | + | + | With parenchymal diffuse ground-glass opacity | |||||

Follicular bronchiolitis | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | Underlying condition such as collagen vascular disease or immunosuppressive disease | |||

Cystic fibrosis | + | + | + | + | + | With bronchiectasis | ||||||

TTM | + | + | + | + | Underlying malignancy such as gastric, ovarian, or lung cancer | |||||||

Mycoplasma Pneumoniae Pneumonia

Pathology and Pathogenesis

Mycoplasmas are the smallest (0.2–0.8 μm) free-living bacteria, but they lack a true cell wall. They are facultative anaerobes, except for Mycoplasma pneumoniae, the most common pulmonary pathogen, which is a strict aerobe. Although it is primarily an infection of young adults, it can attack the elderly. The most common clinical syndrome is tracheobronchitis, with one-third of patients developing a mild but persistent pneumonia. Mycoplasma pneumonia is rarely biopsied, because positive cold agglutinin and specific complement fixation antigen assays establish the diagnosis. Biopsied cases show lymphocytic or neutrophilic bronchiolitis with alveolar wall inflammation and fibrinous exudates [17].

Symptoms and Signs

Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia closely resembles typical pneumonia in the clinical manifestations, such as fever, cough, and purulent sputum. However, patients with Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia commonly have upper respiratory tract manifestations (otitis, bullous myringitis, and mild nonexudative pharyngitis). Extrapulmonary features, such as unexplained watery diarrhea, thrombocytosis, and hemolysis, are also common.

CT Findings

Common thin-section CT (TSCT) findings include centrilobular small nodules and branching linear opacity lesions (tree-in-bud pattern) in a patchy distribution, bronchial wall thickening, and areas of ground-glass opacity (GGO) and consolidation in a lobular or segmental distribution [18, 19] (Fig. 18.4). The abnormalities tend to have a patchy unilateral or asymmetric bilateral distribution, but may be diffuse. Another common abnormality is thickening of the peribronchial interstitium. The CT findings of Mycoplasma pneumonia in children include lobar or segmental consolidation with pleural effusion and regional lymphadenopathy and mild volume loss similar to those of bacterial lobar pneumonia [19]. Most patients with Mycoplasma pneumonia recover completely; however, a small percentage, particularly children, develops bronchiectasis and bronchiolitis obliterans [20].

CT–Pathology Comparisons

Centrilobular small nodules and branching linear opacity lesions on TSCT reflect the presence of cellular inflammatory bronchiolitis. Lobular or segmental consolidation is related to pneumonia caused by extension of infection and concomitant inflammatory reaction into the parenchyma adjacent to the airways [17].

Patient Prognosis

Treatment response is good if timely diagnosed and treated with effective antibiotics, but severe adult respiratory distress syndrome and macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumonia have been reported [21].

Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Pulmonary Disease

Pathology and Pathogenesis

Chronic progressive disease also resembles tuberculosis, with upper lobe thin-walled cavities and granulomatous inflammation, with or without caseous necrosis. This presentation most often is seen in patients with underlying chronic lung disease such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis, pneumoconiosis, reflux disease, or preexisting cavitary lung disease of any cause. The differentiation of tuberculosis from NTM disease could not be accurately made based solely on the histologic features (Fig. 18.5). However, the airway-centered tendency of NTM reflects an airborne etiology, and this could be correlated with the classification according to the radiologic findings. In addition, coexisting constitutional lung diseases, and especially bronchiectasis, were suspected to be predisposing conditions for NTM organisms to colonize and progress to true NTM pulmonary disease [22].

Symptoms and Signs

NTM lung infection presents with diverse manifestations. Symptoms of bronchiectasis including cough, sputum production, and hemoptysis can occur. Tuberculosis-like symptoms, such as fatigue, weight loss, night sweating, and fever, are not uncommon. Some patients may be asymptomatic.

CT Findings

The most common TSCT findings of nodular bronchiectatic form of NTM pulmonary disease include centrilobular small nodules or tree-in-bud pattern, with tubular bronchiectasis, usually in right middle lobe, the lingular segment of left upper lobe, and both the lower lobes [8, 9] (Fig. 18.5). TSCT findings of bronchiectasis and bronchiolitis involving more than five lobes, especially when associated with lobular consolidation or a cavity, are highly suggestive of NTM pulmonary disease [9].

CT–Pathology Comparisons

Centrilobular small nodules, tree-in-bud pattern, and bronchiectasis correspond histopathologically to bronchiectasis and bronchiolar and peribronchiolar inflammation with or without granuloma formation [8]. NTM pulmonary disease is mainly a bronchocentric or bronchiolocentric inflammatory process [23]. It begins with bronchial or bronchiolar wall thickening and develops into peribronchial or peribronchiolar thickening or a peribronchial nodule. Nodular bronchiectatic form of NTM disease on TSCT represents this stage of inflammation mainly involving small airways. During the inflammatory process, the central necrotic portion with destroyed bronchial wall and cartilage seems to be ulcerated and detached into the airway. In this circumstance, the central patent bronchus disposes of the detached central necrotic debris, thus resulting in cavity formation and bronchogenic spread of the infection. Cavitary form of NTM infection on TSCT represents this stage of inflammation mainly involving relatively large airways and more extensive inflammation.

Patient Prognosis

Making a diagnosis of NTM lung disease does not necessitate the institution of therapy. Decision to treat or not should be based on the potential risk and benefit of long-term medical therapy and on the species of NTM [24]. In particular, Mycobacterium abscessus infection is quite resistant to medical therapy [25]. Surgical resection is the one of the treatment options if the lung lesion is localized.

Diffuse Panbronchiolitis

Pathology and Pathogenesis

DPB is a distinctive inflammatory condition characterized by chronic bronchiolitis associated with prominent interstitial vacuolated or “foamy” histiocytes in a peribronchiolar distribution. A genetic susceptibility has been well documented over the years and has been identified as a human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-associated major susceptibility gene [26].

Symptoms and Signs

Common symptoms of DPB are persistent cough, large amount of purulent sputum, and progressive exertional dyspnea [27]. Wheezing and crackles are heard. Superimposed pneumonia can occur. More than 80 % of patients have a history or coexistence of chronic paranasal sinusitis.

CT Findings

The characteristic TSCT findings include centrilobular small nodules and branching linear opacity lesions, bronchiolectasis, bronchiectasis, and mosaic areas of decreased parenchymal attenuation [10] (Fig. 18.6). The presence of these findings is related to the stage of disease: the earliest manifestation consists of centrilobular small nodules, followed by branching opacity lesions that connect to the nodules, followed by bronchiolectasis and, eventually, bronchiectasis. Cystic bronchiectasis may be seen in the late stage [28]. The nodular bronchiectatic form of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease and DPB shows similar imaging findings. However, the number of lobes involved with bronchiectasis and cellular bronchiolitis on TSCT are more numerous in DPB patients [29].

CT–Pathology Comparisons

TSCT findings of centrilobular small nodules and branching linear opacity lesions, bronchiolectasis, and bronchiectasis have been shown to correspond to bronchiolar wall and peribronchiolar inflammation and fibrosis, bronchiolar dilatation with the presence of intraluminal secretions, and dilated air-filled bronchioles. Mosaic areas of decreased parenchymal attenuation are related to air trapping caused by bronchiolar narrowing in the subpleural areas [10].

Patient Prognosis

Long-term low-dose erythromycin therapy is effective for DPB with a 5-year survival rate of 91 % [30]. Prognosis is poor in the advanced cases with extensive bronchiectasis or respiratory failure.

Follicular Bronchiolitis

Pathology and Pathogenesis

Follicular bronchiolitis is characterized by lymphoid follicles containing reactive germinal centers in the walls of bronchioles and occasionally pleura, especially in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (Fig. 18.7). There may be postobstructive changes such as mucostasis and organizing pneumonia and absence of significant lymphoid infiltrate in the adjacent lung parenchyma [31].

Symptoms and Signs

Presenting symptoms include cough, dyspnea, fever, recurrent pneumonia, weight loss, and fatigue [32]. Since follicular bronchiolitis is commonly associated with underlying systemic diseases such as immunodeficiencies and connective tissue diseases, particularly rheumatoid arthritis and Sjögren’s syndrome, clinical manifestations of underlying disease can be found.

CT Findings

The main TSCT findings of follicular bronchiolitis include bilateral centrilobular small nodules and peribronchiolar nodules [11] (Fig. 18.7). Most nodules measure less than 3 mm in diameter but occasionally are as large as 1–2 cm in diameter. Other findings include patchy GGO areas, bronchial wall thickening, and patchy areas of low attenuation.

CT–Pathology Comparisons

Centrilobular small nodules and peribronchiolar nodules on TSCT reflect peribronchiolar inflammation and coalescent germinal centers [11].

Patient Prognosis

The management of follicular bronchiolitis is principally directed at the underlying disease. Corticosteroids and azathioprine therapy have been used with some success in those with progressive follicular bronchiolitis. Prognosis is generally favorable but depends on the underlying condition and the age at the time of biopsy [32].

Pulmonary Tumor Embolism

Pathology and Pathogenesis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree