Chapter 9 Spinal Cord Infarction

Spinal cord infarction remains the less well-studied form of acute ischemic stroke. Although several useful studies describing the clinical and radiological features of spinal cord infarction have been published and the characteristics of the presenting syndrome are fairly well known, its risk factors (apart from aortic dissection and aortic surgery), area of maximal cord involvement, and prognosis are insufficiently understood. Furthermore, it remains a condition with no proven effective treatment.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) allows documentation of spinal cord infarction. However, the true sensitivity of MRI for the early diagnosis of spinal cord ischemia is not well established. Imaging the cord is also important to exclude other causes of acute spinal cord syndrome such as cord compression (from displaced discs, epidural hematomas or abscesses, intradural extramedullary tumors, etc.), spinal cord hemorrhage, dural arteriovenous fistula, multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica, infectious myelitis (e.g., West Nile virus), transverse myelitis (most often negative on early imaging), spinal cord contusion, or intramedullary tumors.1–3 MRI cannot be replaced by any other imaging modality for assessment of spinal cord infarction and exclusion of its differential diagnoses.

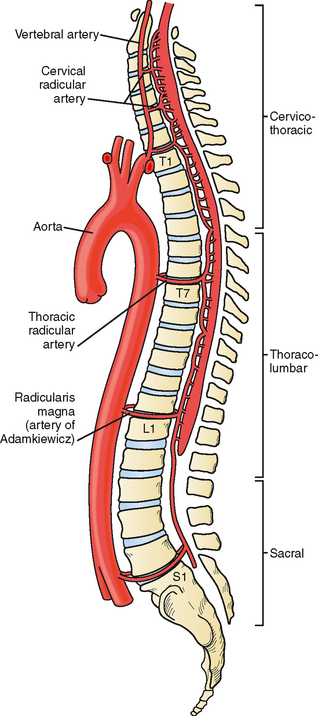

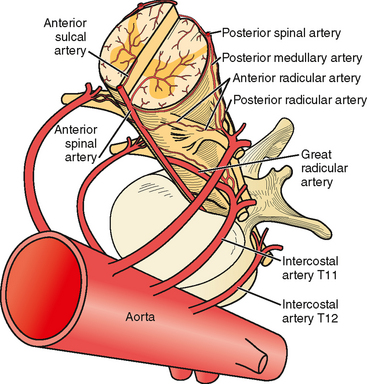

VASCULAR ANATOMY OF THE SPINAL CORD

The anterior spinal artery receives blood from the vertebral arteries in the cervical region and from radicular arteries in the thoracic and lumbar regions. Often two branches arising from each vertebral artery join at the upper cervical level to form the anterior spinal artery; however, many anatomical variations exist and these branches may arise from the posterior inferior cerebellar arteries or from cervical segmental branches. Just a few radicular arteries are responsible for the blood supply to the spinal arteries at the thoracolumbar level. They stem from segmental branches of the aorta (posterior intercostal and lumbar branches), which reach the intervertebral foramina and divide into the anterior and posterior radicular arteries. The largest radicular artery is the arteria radicularis magna of Adamkiewicz (or main anterior radicular artery), which most commonly arises on the left from T9 to T12 but occasionally can be positioned on the right (17% of cases) and arise anywhere from T5 to L4. Between the lower cervical and the mid- to lower thoracic levels, there are usually just two or three small radicular branches supplying this long segment of the cord. Hence the midthoracic area is traditionally considered a watershed territory at high risk for ischemia from hypoperfusion.4,5 Yet most cases of documented spinal cord ischemia do not occur in this area.6–8

Figures 9-1 and 9-2 illustrate the normal vascular anatomy of the spinal cord.

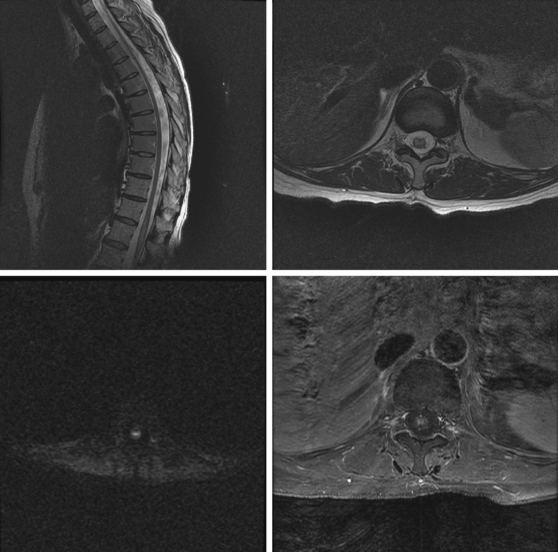

A 52-year-old woman with history of ovarian cancer in remission and no previous vascular disease presented with sudden onset of bilateral leg weakness. She had acute back pain initially, but it was short lasting. There was no loss of sphincter control. In the emergency department, she had flaccid paraplegia and leg areflexia. On sensory examination, she had decreased superficial pain and temperature sensation in both legs, but there was no sensory level detected in the trunk. Proprioception was normal. Computed tomography (CT) angiogram of chest and abdomen excluded aortic dissection but disclosed diffuse atherosclerotic changes throughout the descending aorta. MRI of the thoracolumbar spine revealed changes consistent with acute spinal cord ischemia from T11 to the tip of the conus medullaris (Figure 9-3). She was treated with interventions to optimize blood pressure, intravenous dexamethasone, and lumbar drainage. Over the following 48 hours, her sensation in the legs became nearly normal, but she only regained minimal motor function (some activation of hip flexors). She developed signs of neurogenic bladder and bowel. Comprehensive vascular evaluation uncovered no other mechanisms for the spinal cord ischemia other than aortic atherosclerosis. Three months later, her neurological condition remained unchanged.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree