Fig. 49.1

Array of various leads from percutaneous to paddles

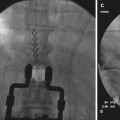

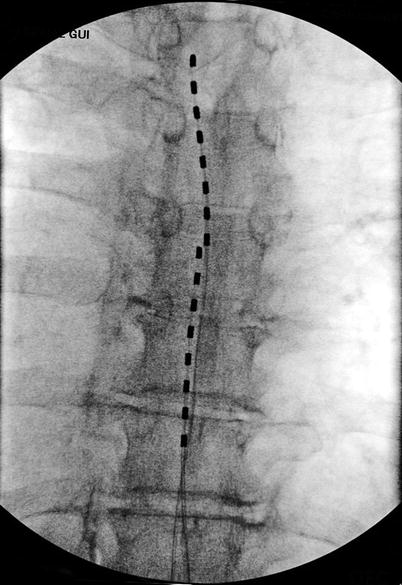

Fig. 49.2

Two leads placed slightly off the midline toward the left dorsal root entry zone. This allows segmental stimulation over the roots affected by the viral injury

Mechanism of Action

The mechanism of action of spinal cord stimulation is based on the placement of epidural electrodes along the dorsal columns. Originally, spinal cord stimulation was called dorsal column stimulation. It is thought that spinal cord stimulation works through the gate-control theory of Melzack and Wall [13] which theorizes that stimulating large nerve fibers (A beta fibers) can inhibit or modulate smaller nerve fibers (A delta or C fibers), transmitting nociceptive input possibly at the dorsal root or horn of the spinal cord. Strategically placed epidural electrodes stimulate the dorsal columns (A beta fibers) to inhibit or modulate incoming nociceptive input through the A delta or C fibers. Ongoing research suggests that spinal cord stimulation may inhibit transmission in the spinothalamic tract, activation of central inhibitory mechanisms influencing sympathetic efferent neurons, and release of various inhibitory neurotransmitters.

Pain Conditions

Spinal cord stimulation can be applied to treat neuropathic pain conditions, including arachnoiditis, complex regional pain syndrome (formerly called reflex sympathetic dystrophy), neuropathies, brachial and lumbosacral plexopathies, radiculopathies, deafferentation syndromes, phantom limb pain, and postherpetic neuralgia. Clinical studies and 30 years of clinical experience have continued to show efficacy in these conditions. Visceral syndromes such as interstitial cystitis, chronic abdominal pain, and chronic pancreatitis have been treated with limited success.

Most randomized controlled trials of chronic neuropathic pain have examined only two pain syndromes: PHN and diabetic neuropathy [17]. In the Practice Parameter: Treatment of Postherpetic Neuralgia, an evidence-based report of the quality standards subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology, published in Neurology in September 2004, excellent overview of treatment options is provided. Overall, the group with the best efficacy with low side effects included gabapentin, lidocaine patch, pregabalin, and tricyclic antidepressants. Opiates remain a controversial option for treatment of PHN or any chronic pain syndrome. In severe cases of either shingles or PHN, epidural steroid injection can be helpful.

Limited success of spinal cord stimulation may depend on the extent of peripheral vascular disease. Based on one study, spinal cord stimulation does not reduce the incidence of amputation in the lower extremities. The same rationale for using spinal cord stimulation for treating peripheral vascular disease is now being applied in clinical trials of patients with intractable angina, including those with patent coronary vessels who continue to have intractable angina and patients who are not candidates for coronary bypass and stent procedures. It is theorized that these patients have a neuropathic condition and microvascular blood flow deficiency.

Some painful conditions cannot be stimulated along the spinal cord and therefore are not responsive to spinal cord stimulation. Thus, peripheral nerve and plexus stimulation has evolved as a complementary neurostimulation approach. The mechanism of peripheral nerve and plexus stimulation is unclear since the electrodes are not stimulating the dorsal columns. Some postulate that a variation of the gate-control theory is involved at the peripheral nervous system level. Moreover, peripheral nerve stimulation may activate central structures, leading to inhibition of various nociceptive pathways, similar to the way acupuncture results in somatosensory cortex activation.

Postherpetic Neuralgia

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree