Spine

Table 1.1 Congenital and developmental abnormalities of the spinal cord or vertebrae |

Table 1.2 Abnormalities involving the craniovertebral junction |

Table 1.3 Intradural intramedullary lesions (spinal cord lesions) |

Table 1.4 Dural and intradural extramedullary lesions |

Table 1.5 Extradural lesions |

Table 1.6 Solitary osseous lesions involving the spine |

Table 1.7 Multifocal lesions and/or poorly defined signal abnormalities involving the spine |

Table 1.8 Traumatic lesions involving the spine |

Table 1.9 Lesions involving the sacrum |

Introduction

Spine and Spinal Cord

Imaging techniques commonly used to evaluate for spinal abnormalities include MRI, MRA, CT, CT myelography, CTA, conventional angiography, and radiographs. MRI is a powerful imaging modality for evaluating normal spinal anatomy and pathologic conditions involving the spine and sacrum. Because of the high soft tissue contrast resolution of MRI and multiplanar imaging capabilities; pathologic disorders of bone marrow (such as neoplasm, inflammatory diseases, etc.), epidural soft tissues, disks, thecal sac, spinal cord, intradural and extradural nerves, ligaments, facet joints, and paravertebral structures are readily discerned to a much greater degree than with CT.

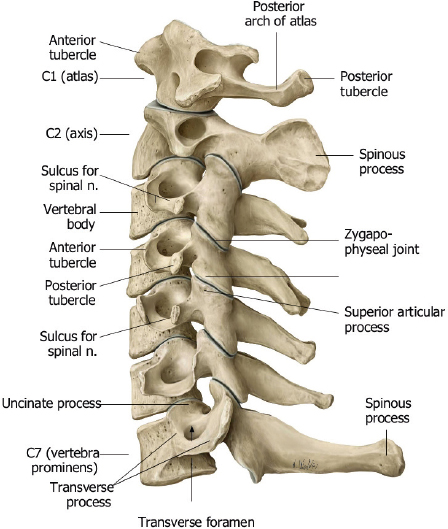

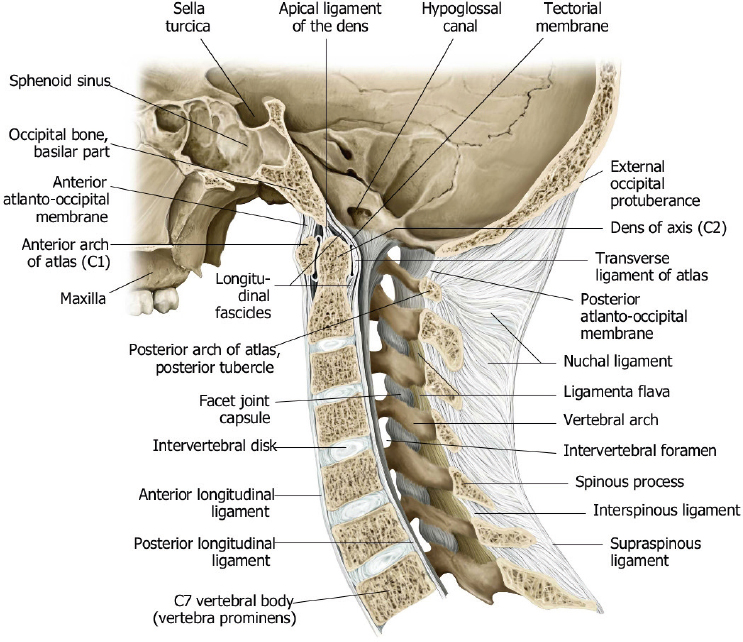

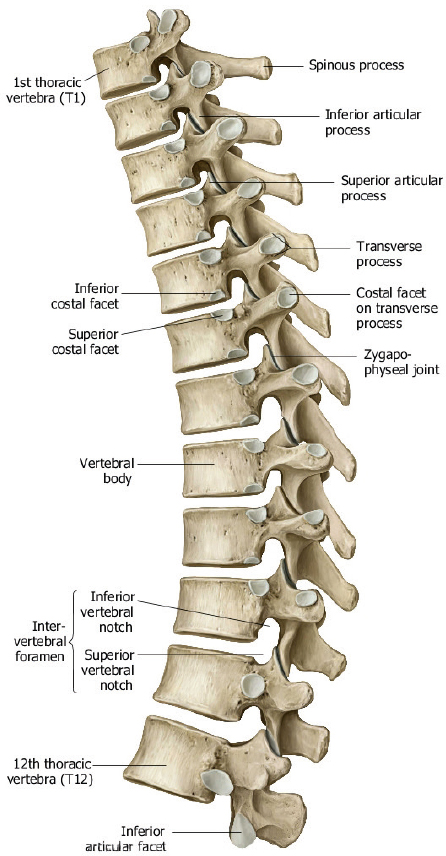

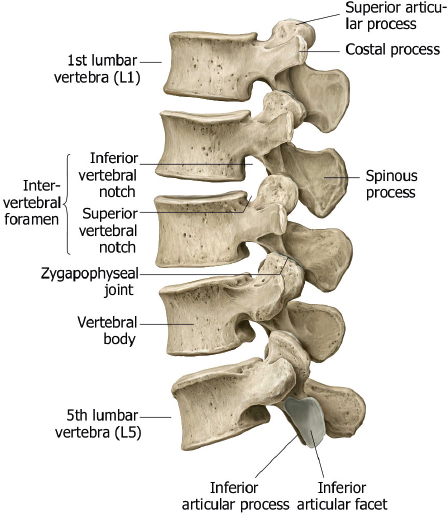

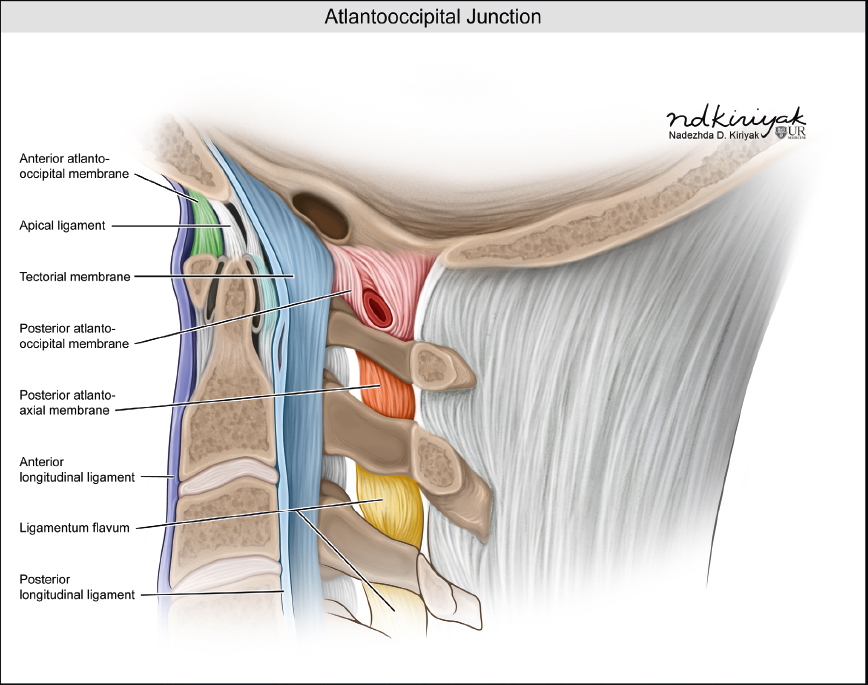

The normal spine is comprised of seven cervical, twelve thoracic, and five lumbar vertebrae ( Fig. 1.1 ). The upper two cervical vertebrae have different configurations than the other vertebrae. The atlas (C1) has a horizontal ringlike configuration with lateral masses that articulate with the occipital condyles superiorly and superior facets of C2 inferiorly ( Fig. 1.2 ). The dorsal margin of the upper dens is secured in position in relation to the anterior arch of C1 by the transverse ligament. Ligaments at the craniovertebral junction include the alar, transverse, and apical ligaments (see Fig. 1.50 and Fig. 1.51 ). The alar ligaments connect the lateral margins of the odontoid process with the lateral masses of C1 and medial margins of the foramen magnum. The alar ligaments limit atlantoaxial rotation. The transverse ligament extends medially from the tubercles at the inner aspects of the lateral articulating masses of C1 behind the dens, stabilizing the dens with the anterior arch of C1. The transverse ligament is the horizontal portion of the cruciform ligament, which also has fibers that extend from the transverse ligament superiorly to the clivus, and inferiorly to the posterior surface of the dens. The apical ligament (middle odontoid ligament) extends from the upper margin of the dens to the anterior clival portion of the foramen magnum. The tectorial membrane is an upward extension from the posterior longitudinal ligament that connects with the body of C2 and the occipital bone (jugular tubercle and cranial base). Other ligaments involved with stabilization of the mid and lower cervical spine include the anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments, ligamenta flava, and nuchal ligament ( Fig. 1.3 ). Various anomalies occur in this region, such as atlanto-occipital assimilation, segmentation (block vertebrae, etc.), basiocciput hypoplasia, condylus tertius, os odontoideum, etc. The lower five cervical vertebral bodies have more rectangular shapes, with progressive enlargement inferiorly. Superior projections from the cervical vertebral bodies laterally form the uncovertebral joints. The transverse processes are located anterolateral to the vertebral bodies and contain the foramina transversaria, which contain vertebral arteries and veins. The posterior elements consist of paired pedicles, articular pillars, laminae, and spinous processes. The cervical spine has a normal lordosis.

The twelve thoracic vertebral bodies and five lumbar vertebral bodies progressively increase in size caudally ( Fig. 1.1, Fig. 1.2, Fig. 1.4 , and Fig. 1.5 ).

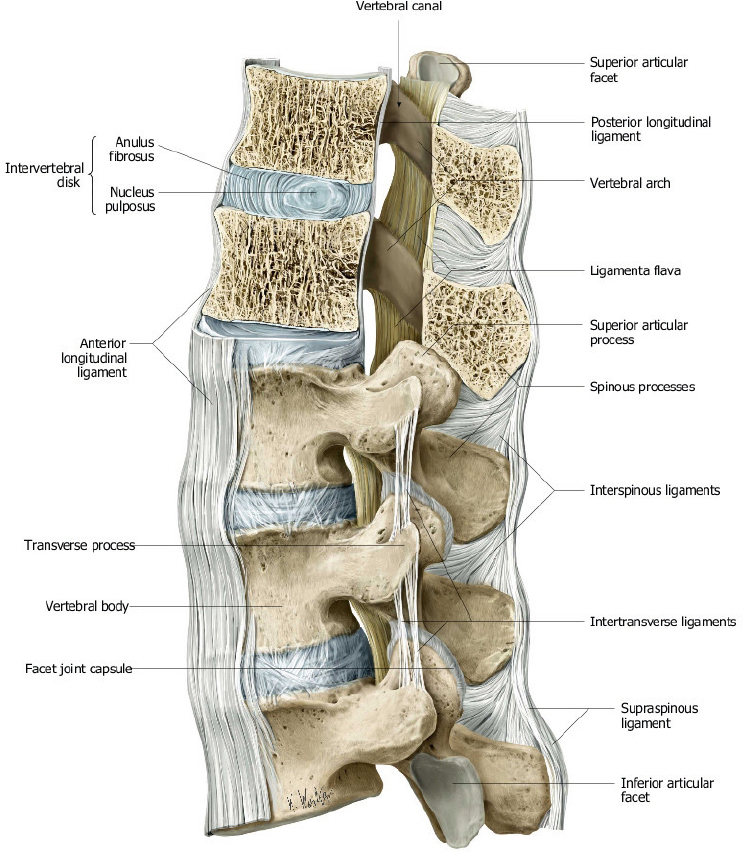

The posterior elements include the pedicles, transverse processes, laminae, and spinous processes. The transverse processes of the thoracic vertebrae also have articulation sites for ribs. The thoracic spine has a normal kyphosis and the lumbar spine a normal lordosis. Anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments connect the vertebrae, and interspinous ligaments and ligamentum flavum provide stability for the posterior elements ( Fig. 1.6 ).

The cortical margins of the vertebral bodies have dense compact bone structure that results in low signal on T1-and T2-weighted images. The medullary compartments of the vertebrae are comprised of bone marrow and trabecular bone. The signal intensity of the medullary compartment is primarily due to the proportion of red versus yellow marrow. The proportion of yellow to red marrow progressively increases with age, resulting in increased marrow signal on T1-weighted images. Similar changes are pronounced in patients who have received spinal irradiation. Pathologic processes (such as tumor, inflammation, or infection) cause increased T1 and T2 relaxation coefficients, which result in decreased signal on T1-weighted images and increased signal on T2-weighted images. MRI with fat-signal suppression techniques (short time to inversion recovery [STIR] sequence, and fat-frequency-saturated T1- and T2-weighted sequences) provide optimal contrast between normal and pathologic marrow. Corresponding abnormal gadolinium enhancement is also usually seen at the pathologic sites, which can also be optimized using fat-frequency-saturated T1-weighted sequences. Because it allows direct visualization of these pathologic processes in the marrow, MRI can often detect the abnormalities sooner than CT, which relies on later indirect signs of trabecular destruction for confirmation of disease.

The intervertebral disks enable flexibility of the spine. The two major components (nucleus pulposus and annulus fibrosus) of normal disks are usually seen well with MRI. The outer annulus fibrosus is made of dense fibrocartilage and has low signal on T1- and T2-weighted images. The central nucleus pulposus is made of gelatinous material and usually has high signal on T2-weighted images. The combination of various factors, such as decreased turgor of the nucleus pulposus, and loss of elasticity of the annulus, with or without tears, results in degenerative changes in the disks. MRI features of disk degeneration include decreased disk height, decreased signal of nucleus pulposus on T2-weighted images, disk bulging, and associated posterior vertebral body osteophytes. Tears of the annulus fibrosus often have high signal on T2-weighted images at the site of injury. Annular tears can be transverse, which are oriented parallel to the outer annular fibers, and are sometimes referred to as annular fissures. Annual tears can also be radial, extending from the central portion of the disk to the periphery. Radial tears are often clinically significant, and are associated with disk herniations. The term disk herniation usually refers to extension of the nucleus pulposus through an annular tear beyond the margins of the adjacent vertebral body end plates. Disk herniations can be further subdivided into protrusions (when the head of the herniation equals the neck in size), extrusions (when the head of the herniation is larger than the neck), or extruded fragments (when there is separation of the herniated disk fragment from the disk of origin). Disk herniations can occur in any portion of the disk. Posterior and posterolateral herniations can cause compression of the thecal sac and contents, as well as compression of epidural nerve roots in the lateral recesses or within the intervertebral foramina. Lateral and anterior disk herniations are less common but can cause hematomas in adjacent structures. Disk herniations that occur superiorly or inferiorly result in focal depressions of the end plates, i.e., Schmorl′s nodes. Recurrent disk herniations can be delineated from scar or granulation tissue because herniated disks do not typically enhance after gadolinium contrast administration, whereas scar/granulation tissue typically enhances.

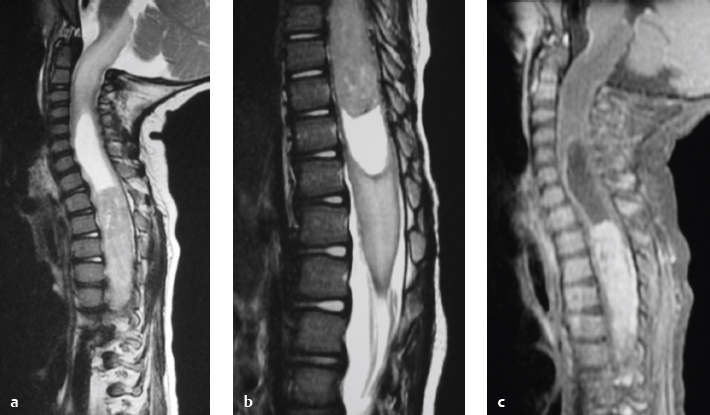

The thecal sac is a meningeal covered compartment that contains cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which is contiguous with the basal subarachnoid cisterns. The thecal sac extends from the upper cervical level to the level of the sacrum, and it contains the spinal cord and exiting nerve roots. The distal end of the conus medullaris is normally located at the T12–L1 level in adults. Lesions within the thecal sac are categorized as intradural and intra- or extramedullary. Intramedullary lesions directly involve the spinal cord, whereas extramedullary lesions do not primarily involve the spinal cord. Extradural or epidural lesions refer to spinal lesions outside of the thecal sac.

The high soft tissue contrast resolution of MRI enables evaluation of various intradural pathologic conditions, such as congenital malformations, neoplasms, benign mass lesions (dermoid, arachnoid cyst, etc.), inflammatory/infectious processes, traumatic injuries (spinal cord, contusions, hematomas), vascular malformations, and spinal cord ischemia/infarction, as well as the adjacent CSF and nerve roots. With the intravenous administration of gadolinium contrast agents, MRI is useful for evaluating lesions within the spinal cord as well as neoplastic or inflammatory diseases within the thecal sac.

The normal blood supply to the spinal cord consists of seven or eight arteries that enter the spinal canal through the intervertebral foramina, which divide into anterior and posterior segmental medullary arteries to supply the three main vascular territories of the spinal cord (cervicothoracic—cervical and upper three thoracic levels; mid thoracic—T4 level to T7 level; and thoracolumbar—T8 level to lumbosacral plexus) ( Fig. 1.7 and Fig. 1.8 ). The cervicothoracic vascular distribution is supplied by radicular branches arising from the vertebral arteries and costocervical trunk. The midthoracic territory is often supplied by a radicular branch at the T7 level. The thoracolumbar territory is supplied by a single artery arising from the ninth, tenth, eleventh, or twelfth intercostal arteries (75%); the fifth, sixth, seventh, or eighth intercostal arteries (15%); or the first or second lumbar arteries (10%). The artery is referred to as the artery of Adamkiewicz. The anterior segmental medullary arteries supply the longitudinally oriented anterior spinal artery, which is located in the midline anteriorly adjacent to the spinal cord and supplies the gray matter and central white matter of the spinal cord. The posterior segmental medullary arteries also supply the two major longitudinally oriented posterior spinal arteries, which course along the posterolateral sulci of the spinal cord and supply one-third to one-half of the outer rim of the spinal cord via a peripheral anastomotic plexus. Ischemia or infarcts involving the spinal cord are rare disorders associated with atherosclerosis, diabetes, hypertension, abdominal aortic aneurysms, and abdominal aortic surgery. Venous blood from the spinal cord drains into the anterior and posterior venous plexuses, which connect to the azygos and hemiazygos veins via the intervertebral foramina ( Fig. 1.9 ). Vascular malformations can be seen within the thecal sac, with or without involvement of the spinal cord.

Epidural structures of clinical importance include the lateral recesses (anterolateral portions of the spinal canal located between the thecal sac and pedicles and that contain nerve roots, vessels, and fat), the dorsal epidural fat pad, the posterior elements and facet joints, and the posterior longitudinal ligament and ligamentum flavum. The intervertebral foramina are bony channels between the pedicles through which the nerves traverse.

Narrowing of the thecal sac, lateral recesses, and intervertebral foramina can result in clinical signs and symptoms. Narrowing can be caused by disk herniations, posterior vertebral body osteophytes, hypertrophy of the ligamentum flavum and facet joints, synovial cysts, excessive epidural fat, epidural neoplasms, abscesses, hematomas, spinal fractures, and spondylolisthesis or spondylolysis. MRI is useful for evaluating these disorders and for categorizing the degree of narrowing of the thecal sac, as well as compression of nerve roots in the lateral recesses and intervertebral foramina.

Spinal Development

During the second week of gestation, the developing embryo consists of a layer of cells adjacent to the yolk sac referred to as the hypoblast, and a layer of cells adjacent to the amnion referred to as the epiblast. Cells in the midline of the embryo form the primitive knot (Hensen′s node) and adjacent primitive streak posteriorly. At the beginning of the third week, cells from the rostral portion of the primitive streak (Hensen′s node) extend between the epiblast and hypoblast to eventually form the notochord. The gastrulation stage of development of the spine begins during the third week of gestation, when the bilaminar embryonic disk differentiates into a trilaminar disk consisting of endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm ( Fig. 1.10 ). During the third week of gestation, the notochord induces the overlying ectoderm to form the neural plate, which thickens and folds to form the neural tube (this process is referred to as primary neurulation) ( Fig. 1.10 ) . After 5 weeks, the embryonic caudal cell mass forms the secondary neural tube, which will form the tip of the conus medullaris and filum terminale in a process referred to as secondary neurulation.

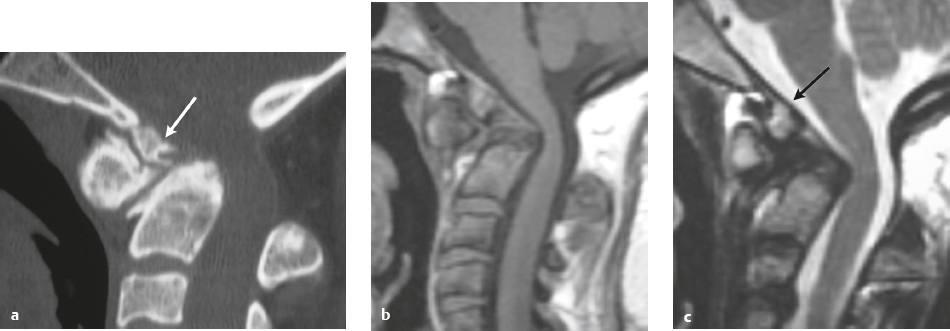

Between the fourth and fifth weeks of gestation, the notochord also induces adjacent paraxial mesoderm (derived from the primitive streak) to form bilateral somites, which form the myotomes that will eventually develop into the paraspinal muscles and skin and the sclerotomes that will develop into the bones, cartilage, and ligaments of the spinal column ( Fig. 1.10 and Fig. 1.11 ). At 5 weeks, each sclerotome separates into superior and inferior halves, which fuse with corresponding halves of the adjacent sclerotomes to form the vertebral bodies (this process is referred to as resegmentation). Portions of the notochord between the newly formed vertebral bodies evolve into the nucleus pulposus of each disk. Chondrification of the vertebrae occurs after 6 weeks, followed by ossification after 9 weeks. Except for C1 and C2, each vertebra has two ossification centers in the vertebral body that merge, and single ossification centers in each side of the vertebral arch ( Fig. 1.12 ). In C1, a single ossification center or two or more ossification centers can occur in the anterior arch. Six ossification centers and four synchondroses typically occur in C2 ( Fig. 1.13 ).

Disruption of any of these developmental processes can lead to the various anomalies of the spinal cord or vertebrae.

Table 1.1 Congenital and developmental abnormalities of the spinal cord or vertebrae

Congenital and Developmental Abnormalities Involving Neural Tissue and Meninges

Chiari I malformation

Chiari II malformation (Arnold-Chiari malformation)

Chiari III malformation

Myelomeningocele/Myelocele

Myelocystocele

Lipomyelocele/Lipomyelomeningocele

Intradural lipoma

Dorsal dermal sinus

Tethered spinal cord, thickened filum terminale

Fibrolipoma of the filum terminale

Meningocele

Diastematomyelia (split-cord malformation)

Ventriculus terminalis of the conus medullaris

Neurenteric cyst

Epidermoid

Dermoid

Congenital and Developmental Abnormalities Involving Vertebrae

Atlanto-occipital assimilation/Nonsegmentation

Atlas anomalies

Os odontoideum

Klippel-Feil anomaly

Sprengel deformity

Hemivertebrae

Butterfly vertebra

Tripediculate vertebra

Spina bifida occulta

Spina bifida aperta (Spina bifida cystica)

Syndrome of caudal regression

Short pedicles—Congenital/developmental spinal stenosis

Genetic Developmental Abnormalities of the Spine

Achondroplasia

Neurofibromatosis type 1

Marfan syndrome

Mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS)

Spondylometaphyseal dysplasia (SMD)

Abnormalities Involving the Craniovertebral Junction

The craniovertebral junction consists of the occipital bone, C1 and C2 vertebrae, and connecting ligaments. The articulations of the occipital-atlanto (C0–C1) and atlanto-axial (C1–C2) joints are different from the lower cervical levels. With the occipital-atlanto articulation, the occipital condyles rest along the superior facets of the lateral masses of C1. This configuration allows for 20 degrees of flexion and extension while limiting axial rotation and lateral flexion. With the C1–C2 articulation, a small rounded facet (fovea dentis) at the dorsal aspect of the anterior arch of C1 articulates with the anterior margin of the dens. This configuration enables the skull and atlas to rotate laterally as a unit around the vertical axis of the dens. Ligaments at the craniovertebral junction include the alar, transverse, and apical ligaments ( Fig. 1.50 and Fig. 1.51 ). The alar ligaments connect the lateral margins of the odontoid process with the lateral masses of C1 and medial margins of the foramen magnum. The alar ligaments limit atlanto-axial rotation. The transverse ligament extends medially from the tubercles at the inner aspects of the lateral articulating masses of C1 behind the dens, stabilizing the dens to the anterior arch of C1. The transverse ligament is the horizontal portion of the cruciform ligament, which also has fibers that extend from the transverse ligament superiorly to the clivus and inferiorly to the posterior surface of the dens. The apical ligament (middle odontoid ligament) extends from the upper margin of the dens to the anterior clival portion of the foramen magnum. The tectorial membrane is an upward extension from the posterior longitudinal ligament that connects with the body of C2 and the occipital bone (jugular tubercle and cranial base). Above the C2 level, the tectorial membrane merges with dura mater. The anterior and posterior atlanto-occipital membranes are superior extensions of the flaval ligament.

Table 1.2 Abnormalities involving the craniovertebral junction

Congenital and Developmental

Basiocciput hypoplasia

Chiari I malformation

Chiari II malformation

Chiari III malformation

Condylus tertius

Atlanto-occipital assimilation/nonsegmentation

Atlas anomalies

Os odontoideum

Achondroplasia

Down syndrome (Trisomy 21)

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

Mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS)

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI)

Neurenteric cyst

Ecchordosis physaliphora

Osteomalacia

Renal osteodystrophy/secondary hyperparathyroidism

Paget disease

Fibrous dysplasia

Hematopoietic disorders

Traumatic Lesions

Fracture of skull base

Atlanto-occipital dislocation

Jefferson fracture (C1)

Hangman′s fracture (C2)

Odontoid fracture (C2)

Inflammation

Osteomyelitis/epidural abscess

Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate (CPPD) deposition

Malignant Neoplasms

Metastatic disease

Myeloma

Chordoma

Chondrosarcoma

Squamous cell carcinoma

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma

Adenoid cystic carcinoma

Invasive pituitary tumor

Benign Neoplasms

Meningioma

Schwannoma

Neurofibroma

Tumorlike Lesions

Epidermoid

Arachnoid cyst

Mega cisterna magna

Table 1.3 Intradural intramedullary lesions (spinal cord lesions)

Neoplasms

Astrocytoma

Ependymoma

Ganglioglioma

Hemangioblastoma

Glioneuronal tumor

Oligodendroglioma

Primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET)

Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor

Metastatic tumor

Demyelinating Disease

Multiple sclerosis (MS)

Neuromyelitis optica

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM)

Transverse myelitis

Other Noninfectious Inflammatory Disease Involving the Spinal Cord

Sarcoidosis

Sjögren syndrome

Infectious Diseases of Spinal Cord

Viral infection

Abscess/nonviral infectious myelitis

Parasitic infection

Vascular Lesions

Intramedullary hemorrhage

Posthemorrhagic lesions

Arteriovenous malformation (AVM)

Cavernous malformation

Venous angioma (Developmental venous anomaly)

Spinal cord infarct/ischemia of arterial etiology

Ischemia—Venous infarction/congestion

Traumatic Lesions

Spinal cord contusion

Spinal cord transection

Chronic injury

Degenerative Abnormalities

Myelomalacia

Wallerian degeneration

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

Poliomyelitis

Radiation myelopathy

Other Lesions

Syringohydromyelia

Vitamin B12 deficiency (Subacute combined degeneration)

Superficial siderosis

Table 1.4 Dural and intradural extramedullary lesions

Congenital and Developmental

Meningocele

Dural dysplasia/ectasia

Dorsal dermal sinus

Dermoid

Epidermoid

Neurenteric cyst

Fibrolipoma of the filum terminale

Neoplasms

Ependymoma

Schwannoma (Neurinoma)

Meningioma

Neurofibroma

Paraganglioma

Teratoma

Hemangioma

Hemangioblastoma

Hemangiopericytoma

Solitary fibrous tumors (SFTs)

Primitive neuroectodermal tumor

Leptomeningeal neoplastic disease

Lymphoma

Leukemia

Primary melanocytic tumors of the central nervous system

Infection

Bacterial infection

Fungal infection

Viral infection

Noninfectious Dural and Leptomeningeal Disorders

Sarcoidosis

Guillain-Barré syndrome

Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy

Radiculitis

Adhesive arachnoiditis

Arachnoiditis ossificans

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener′s granulomatosis)

Idiopathic hypertrophic pachymeningitis

Vascular Lesions

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs)

Hemorrhage within CSF (Subarachnoid hemorrhage)

Subdural hemorrhage

Acquired Lesions

Perineural cysts/Tarlov cysts

Arachnoid cyst

Pseudomeningocele

CSF leak/fistula

Spinal cord herniation

Intradural herniated disk

Calcifying pseudoneoplasm of the neuraxis (CAPNON)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree