Anal cancer is a relatively rare malignancy. Treatment consists of chemoradiation and most patients achieve a complete response. Local evaluation of the T and N stage is performed by MR imaging. Whole-body staging with 18F-fluorodesoxyglucose positron emission tomography computed tomography scans or computed tomography scans is used to detect metastases. T stage is based on tumor size or invasion of organs. N stage is based on nodal location. After chemoradiation, clinical evaluation and MR imaging is used to assess tumor and nodal response. Maximal response is achieved 6 months after chemoradiation. Beware of development of anal cancer in perianal fistulas.

Key points

- •

Anal cancer is a relatively rare malignancy and treatment mostly consists of chemoradiation.

- •

T staging depends on tumor size and on invasion of surrounding organs.

- •

N staging is determined by nodal location.

- •

MR imaging is the mainstay of local staging and is performed at primary staging and 6 to 8 weeks after chemoradiation therapy to assess tumor and nodal response.

- •

Maximal response is expected at 6 months from chemoradiation therapy, and a complete response is obtained in 90% of patients.

Introduction

Anal cancer is a relatively rare malignancy that occurs in the anal canal or the perianal skin within 5 cm of the anal margin. Approximately 8200 new cases are found annually in the United States and anal cancer makes up 2.6% of all digestive cancers. The majority of cases concern squamous cell carcinoma; less common are adenocarcinoma or melanoma. Most patients present with anal itch, bleeding or pain. However, some patients are asymptomatic. Often complaints are mistaken for hemorrhoids or fissures, leading to a substantial delay in diagnosis in many cases. Risk factors for anal cancer are presence of human papillomavirus, human immunodeficiency virus seropositivity, smoking, passive anal intercourse, and having multiple sex partners. Staging is performed by clinical examination with proctoscopy, ultrasound (inguinal area) examination, MR imaging, and 18F-fluorodesoxyglucose positron emission tomography computed tomography ( 18 F-FDG PET-CT) scans. Treatment is aimed at providing cure while maintaining the best sphincter function possible. Depending on the location and staging, treatment can consist of surgery (local excision or abdominoperineal resection) and/or chemoradiation. Tumors in the anal margin (the skin surrounding the anal verge) are generally treated with local excision. Tumors in the anal canal itself are usually too large to excise locally (local excision is only an option in tumors <1 cm) and in these cases chemoradiation is given. Radiation preferably consists of intensity-modulated radiotherapy, to achieve the lowest toxicity possible. Chemoradiation consists of a total dose of 45.0 to 50.4 Gy on the primary target area, delivered in fractions of 1.8 to 2.0 Gy. This treatment is usually followed by a boost of radiation of 15 to 25 Gy. The radiation field includes the primary tumor, the anal canal and margin and regional nodal areas (in tumors >1–2 cm or N+ stage). Regional nodal areas include the internal pudendal nodes, internal and external iliac nodes and the mesorectal nodes for tumors above the dentate line. For tumors below the dentate line, inguinal nodes are irradiated as well. Concomitant chemotherapy consists of mitomycin C combined with capecitabine or 5-fluorouracil or 5-fluorouracil with cisplatin. When there is N+ disease, there will generally be a boost on the involved nodal regions or lymph node dissection will be performed.

Maximal response is obtained 6 months after chemoradiation. In 80% to 90% of cases, a complete response is found and the patient is then followed up. In case of an incomplete response, salvage surgery can be performed by abdominoperineal resection, combined with groin dissection in case of metastatic inguinal nodes. Sometimes (if extensive invasion is present) it is necessary to perform a larger excision (by extralevatoric abdominoperineal resection). In case of recurrence, abdominoperineal resection is the treatment of choice, if possible.

Normal anatomy and imaging techniques

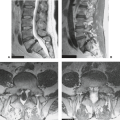

Anatomy

The anal anatomy comprises multiple cylindrical layers ( Fig. 1 ). Innermost is the mucosa and submucosa lining the anal canal; in the inferior part this is (sub)epithelium. Next is the smooth muscle internal sphincter, which is the continuation of the circular layer of the rectal wall. The internal sphincter lower edge is approximately 1 cm above the caudal edge of the anal sphincter. Next is the intersphincteric space with next to this the outer striated muscle layer of the anal sphincter that constitutes the circular external sphincter and sling-like puborectal muscle. The external sphincter is approximately the lower half of the outer layer and the puborectal muscle the upper outer half. The anal sphincter is continuous with the rectum at the anorectal junction, with at this level also the levator plate that attaches to the fascia of the internal obturator muscle.

Imaging Technique and Protocol

For local evaluation MR imaging is the main modality in anal cancer, specifically for tumors of 2 cm and larger. At least 90% of the cases the anal cancer is visible on MR imaging. MR imaging offers a high spatial resolution and can demonstrate anal anatomy most accurate. A typical protocol consists of 3 T2-weighted sequences in sagittal, axial and coronal plane, angled perpendicular or parallel to the anal canal. A T1-weighted sequence covering the whole pelvis is required to image nodal disease. A fat-saturated T2 sequence can be used in case of pre-existing fistulae. Additionally, a diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) sequence can be used, which can help in identification of a lesion and has potential to help in response assessment after chemoradiation, similar to rectal cancer.

Whole body staging for locoregional nodes, distant nodes and distant metastases is performed with a 18 F-FDG-PET-CT scan. The area from groin to skull base is covered. Anal cancers are almost always highly 18 F-FDG avid and thus sensitivity for metastases is high.

For nodal staging of the groin area ultrasound with fine needle aspiration is used, sometimes routinely, but often after 18 F-FDG-PET-CT scan to perform aspiration based on suspicious nodes on 18 F-FDG-PET-CT scan. More distant nodes are staged with MR imaging and/or 18 F-FDG-PET-CT scan.

Endorectal ultrasound (EUS) is useful to evaluate local transmural extension of the tumor, but only in experienced hands. EUS is not valuable for nodal staging, therefore, MR imaging is the mainstay of imaging the local disease in anal cancer. ,

Imaging findings and diagnostic criteria of anal cancer

T Stage

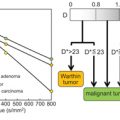

The T stage in anal cancer is based on tumor size. T1 tumors are up to 2 cm in size; T2 tumors 2 to 5 cm; T3 tumors larger than 5 cm; and when a tumor invades other structures it is a T4 tumor. Structures that can be invaded and will classify the tumor as T4 are puborectal or levator muscle, prostate, seminal vesicles, vagina, uterus/adnexa, bone, piriform muscle, or obturator muscles. Specifically, direct invasion in the rectal wall, perineal skin, and perianal subcutaneous tissues and the internal and/or external sphincter muscle are not deemed as T4 tumors. In tumors with T stage 2 to 4 chemoradiation is indicated; depending on the location in T1 tumors local excision or chemoradiation can both be considered.

T staging is performed by MR imaging primarily, but as briefly mentioned, there is also a role for EUS. EUS has been reported to be able to show the anal cancer in 100% of the cases. Also, evaluation of T1 tumors EUS is a good option, mainly because MR imaging has difficulty to detect such small lesions. 18 F-FDG-PET-CT scans can detect almost all lesions (99% detection rate), but is not helpful for T staging.

DWI can help in the detection of the anal cancer, when it is difficult to identify the tumor on T2-weighted images. For T staging DWI is not advised, but a recent article has shown that DWI-based volumetry of the tumor (to establish the target volume for radiation) leads to a lower size measurement of the tumor than if T2-weighted (T2W) MR imaging if used. So, possibly DWI can have a role in tumor staging, but this needs to be explored.

N Stage

Once evaluation of the primary tumor has been completed, whole body imaging should be performed to evaluate for lymphadenopathy or distant metastasis. According to the eighth TNM staging edition, N stage can be categorized into 5 categories, depending on the location of the nodes, whereas in the seventh edition only the number of malignant nodes was relevant for N staging. The eighth TNM staging edition is based on the regional lymphatic drainage of the anorectal region. Regional nodal metastasis spreads to the inguinal regions (mostly in tumors confined to the anal canal below the dentate line), mesorectal compartment (if above the dentate line or when the rectal wall is involved), and/or the internal and external iliac chain. In the nodal staging classification system, N0 means that there are no regional lymph node metastases. N1 indicates regional lymph node metastases and is divided into 3 categories: N1a, metastasis in inguinal, mesorectal and/or internal iliac nodes; N1b, metastasis in external iliac nodes; and N1c, metastasis in external iliac and in inguinal, mesorectal and/or internal iliac nodes (so, a combination of N1a and N1b). Nodes further along the common iliac artery or aorta are considered M1 disease. Nx indicates that nodal stage cannot be assessed or is not assessed yet. In about 25% to 45% of anal cancers, there is nodal involvement. Nodal involvement leads to a higher risk for local failure and a worse 5-year disease-free and overall survival in patients with T2 to T4 tumors.

Locoregional nodes are depicted on MR imaging, but as in other cancers, it is challenging to stage nodes based on anatomic imaging such as MR imaging and CT scanning. Size criteria often lead to substantial understaging and overstaging. Therefore, nodal staging relies on ultrasound and 18 F-FDG-PET-CT scans. Ultrasound signs of malignancy are round shape, short axis size of greater than 1 cm, loss of fatty hilum, and a thickened or asymmetric cortex. Usually in stage cT1 and greater anal cancer 18 F-FDG-PET-CT scanning is performed and nodal spread can be evaluated. Based on the results of the 18 F-FDG-PET-CT scan, targeted ultrasound imaging can be performed to evaluate the morphologic aspect and size of inguinal nodes and perform a fine needle aspiration in 18 F-FDG avid or morphologically suspicious nodes. When nodes are evaluated on MR imaging and CT scans, enlargement and the presence of necrosis will be the most suspicious features for node malignancy. Additionally, irregularity, asymmetry, or signal heterogeneity are suspicious findings and these findings are best assessed by MR imaging given the high spatial resolution and high contrast between tissues. Unfortunately, size criteria have a disappointing accuracy (leading to false-negative findings in small nodes and false-positive findings in large nodes), similar to the accuracy in rectal cancer (with a sensitivity of 66% and specificity of 76%). When using MR imaging for nodal staging, short axis size cutoffs of 8, 5, and 10 mm have been proposed for pelvic, mesorectal, and inguinal nodes, respectively. These morphologic criteria are less easy to apply in nodes less than 5 mm. 18 F-FDG-PET-CT scanning provides better accuracy for nodal staging, with an alteration in nodal stage in 28% of the cases when added after other imaging. A meta-analysis from Jones and colleagues reported a sensitivity of 99% for nodal staging by 18 F-FDG-PET-CT scan, compared with 60% with a CT scan. However, another meta-analysis reported a pooled sensitivity of only 56% for 18 F-FDG-PET-CT scan. Specificity is high and ranges from 90% to 100%, respectively. However, 18 F-FDG-PET-CT scanning has a limited resolution and can miss metastases in nodes less than 5 mm. So, in current practice small nodes in particular pose a problem. Figs. 2–6 show several examples of anal cancers with different T and N stages.

M Staging

As mentioned, nodes further along the common iliac artery or aorta are considered M1 disease. M staging is only based on the absence or presence of metastases. In the TNM classification M0 means no distant metastasis and M1 means distant metastasis. For anal cancer, no difference is made between regional, solitary or multiple metastases. The literature shows that approximately 6% of squamous cell anal carcinomas are metastatic at diagnosis. , Patients with metastatic disease have a prognosis with 5-year median overall survival rates of 10% in men and 20% in women.

A particular group easily overlooked is nodes just below the aortic bifurcation. Beside the lymph nodes, mainly the liver and the lungs are involved.

To rule out distant metastases, a chest and abdomen CT scan with intravenous contrast is advised. Preparation with oral contrast is advised in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2017 guidelines, but preparation with water is sufficient in the authors’ experiences. If available, 18 F-FDG-PET-CT scanning can be considered. Anal cancers and their metastases are almost always highly FGD avid and sensitivity for metastases is therefore high. A systemic review proposes that 18 F-FDG-PET-CT scans may aid in treatment monitoring and might help in the selection of patients who may benefit from more aggressive treatment. Therefore, 18 F-FDG-PET-CT scans might be helpful for monitoring therapy, the detection of recurrent disease and establishing the presence of distant metastases. However, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2017 guidelines do not consider 18 F-FDG-PET-CT scans to be a replacement for a diagnostic CT scan.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree