Chapter 37 Stellate Ganglion Block

Note: Please see page ii for a list of anatomical terms/abbreviations used in this book.

Stellate ganglion blocks are used for the treatment of a variety of painful medical conditions that range from sympathetically mediated pain and post-herpetic neuralgia in the upper limbs1, head, and neck2 region to pain that is associated with intractable angina.3

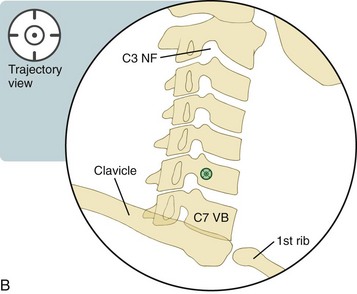

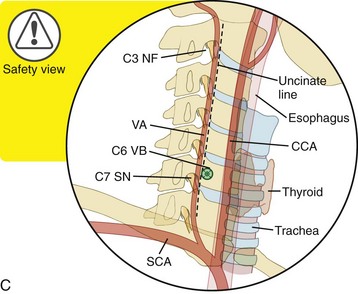

Historically, anesthetic has been injected at the level of the C6 vertebrae, because prominent landmarks such as the anterior tubercle of the C6 vertebrae (i.e., the Chassaignac tubercle), the cricoid cartilage, and the carotid artery have been used when performing non–image-guided (i.e., blind) injections.4 A C7 approach has also been described.5 Both levels are considered acceptable in current practice. However, given the higher risk of pneumothorax and vertebral artery puncture at the C7 level, the C6 level has become the more common approach to be used by practitioners.6 Given the relative risk of this procedure, fluoroscopic guidance should be used.

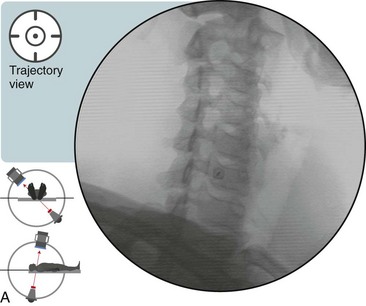

Contrast injected at the C6 level has consistently reached the C7-T1 interspace, which is the commonly accepted location of the stellate ganglion.7 Ideal injectate spread should extend down to T2 for upper limb symptoms. The anterior (foraminal) oblique approach is advantageous over the traditional (i.e., paratracheal) approach, because it provides an unobstructed trajectory view (i.e., it does not require pushing vascular structures out of the way and radiating the interventionalist’s hands). With multiplanar imaging, the risk of encountering dangerous structures is minimized.

Recall that the stellate ganglion is composed of the inferior cervical ganglion (C7) and proximal thoracic ganglion (T1), which are fused together in 80% of the general population.6 This location is usually anterior to the neck of first rib, and it extends into the interspace between the C7 and T1 vertebral bodies. If elongated, it may rest on the anterior tubercle of C7. If it is not fused, then the individual ganglia are usually anterior to the neck of the first rib and adjacent to the anterior C7 tubercle.8 In this situation, the proximal thoracic ganglion is considered to be the stellate ganglion.

Contraindications are similar to those of other interventional spine procedures, with a few notable additions, including cardiac conduction block and the risk of bullous puncture in patients with severe emphysema.5 Only one side should be injected per session. Bilateral injections tend to result in high local anesthetic doses with associated vascular responses. Also, if both sides are blocked, hazardous side effects include bilateral recurrent laryngeal block, which can cause stridor.

Clinical signs and symptoms that suggest a successful block include the immediate development of Horner’s syndrome (see Figure 37–5); ptosis (i.e., drooping of the upper eyelid from a loss of sympathetic innervation to the superior tarsal muscle); miosis (i.e., constricted pupil); anhidrosis (i.e., decreased sweating on the affected side of the face); and the development of a stuffy nose and increased facial and upper limb temperature on the ipsilateral side within 5 minutes of the procedure (i.e., Guttman’s sign).4 Occasionally, conjunctiva redness and unilateral fascial flushing may also be observed. A change in heart rate is not a reliable indicator of a successful block.8 A decrease in pain will also typically accompany a successful block. Ideally, patients should have therapy scheduled immediately after the procedure for functional reassessment and aggressive treatment.