Suprascapular Nerve Block Technique

The technique of the SSNB can be performed utilizing either a direct or indirect technique. The direct technique involves blocking the suprascapular nerve at the suprascapular notch, just as the nerve enters the supraspinous fossa [1, 21, 32–34]. The patient is placed in a seated position with the hands resting on the thighs. A line is drawn along the scapular spine from the tip of the acromion to the medial border of the scapula. After identifying the inferior angle of the scapula, a second line bisecting this angle is drawn and extended upward as far as the superior border of the scapula, intersecting the line drawn along the scapular spine and forming four quadrants (Fig. 28.2). The angle of the upper outer quadrant is bisected, and a point is marked on the line 1.5 cm from the apex of the angle. After the area is prepped and draped, the needle is advanced perpendicularly until the scapula is contacted and then redirected until it slides into the suprascapular notch. At this point, the needle is slightly withdrawn, aspiration is performed to rule out intravascular location, and local anesthetic is injected [1, 14]. Some authors describe utilizing a nerve stimulator to visually confirm contraction of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles to verify proximity to the suprascapular nerve prior to placing the injectate. Keratas and Meray utilized EMG guidance with the direct technique to confirm proximity to the suprascapular nerve and reported superior results to traditional methods [14]. While the theoretical advantage of the direct technique includes placing the injectate immediately next to the suprascapular nerve as it emerges from the suprascapular notch, there is a slight increased risk of pneumothorax.

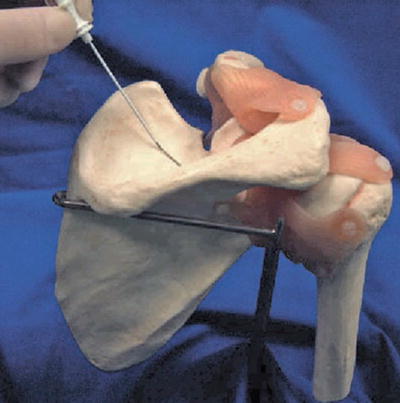

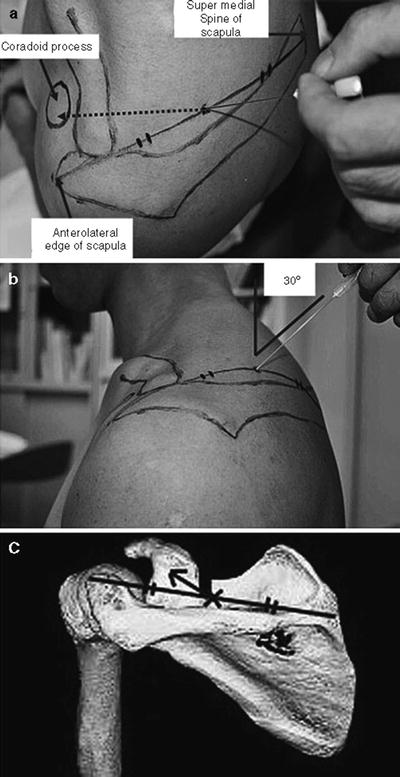

Fig. 28.2

Suprascapular nerve block. A line is drawn along the scapular spine and then bisected by a second line parallel to the vertebral spine. The entry point is 2–3 cm into the upper outer quadrant. The needle is directed from the top to avoid deep entry into the suprascapular notch, which could risk pneumothorax (From Rathmell et al. [35], with permission)

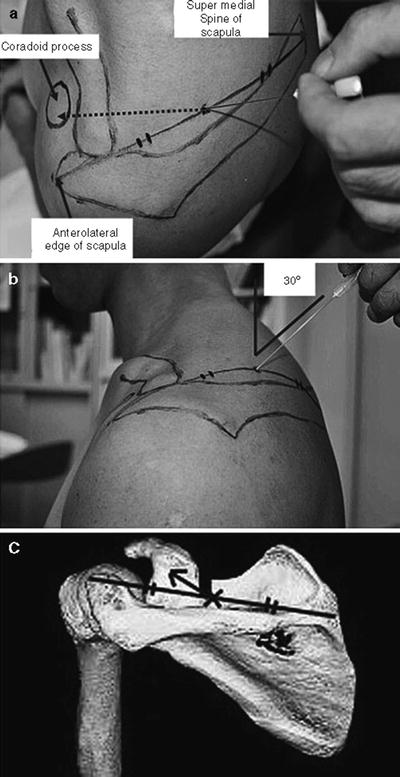

In more recent years, some investigators have advocated various versions of an indirect technique that involves placing the needle away from the suprascapular notch to avoid the risk of pneumothorax [36]. Dangiosse et al. described blocking the suprascapular nerve by injecting the local anesthetic into the floor of the suprascapular fossa [11]. The needle is introduced into the fossa 1 cm cephalad to the middle of the spine of the scapula, parallel to the blade, and until the bony floor of the supraspinous fossa is reached. Meier et al. described another variance to the indirect technique by drawing a line from the medial end of the spine of the scapula to the lateral posterior border of the acromion. After halving this line, the injection site is established 2 cm medial and 2 cm cranial from this point (Fig. 28.3). Using a 22-gauge, 6-cm needle, and nerve stimulator, the needle is advanced in a lateral direction on the floor of the fossa at an angle of 75° to the skin surface and toward the head of the humerus. Based on cadaveric studies showing the sensory branches of the suprascapular nerve course along the base of the coracoid process, Matsumoto et al. proposed blocking the nerve fibers at this location. The insertion point is the midpoint of the anterolateral angle of the acromion and the medial edge of the scapular spine. The needle is inclined at a 30° angle toward the dorsal direction from the axis of the body and inserted until it reaches the base of the coracoid process (Fig. 28.4). Preliminary results in eight patients experiencing severe pain after rotator cuff repair surgery resulted in effective pain relief. The average postoperative VAS scores of the eight patients were 5.4 ± 2.7. Notably, the volume of injectate varies in most reports from 5 to 15 ml while performing either the direct or indirect technique although most reported using a volume of 10 ml of local anesthetic.

Fig. 28.4

(a) The needle is inserted to contact the bone toward the coracoid process from the midpoint of the anterolateral edge of the acromion and super medial angle of the scapular spine. (b) The needle is inclined at a 30° angle toward the dorsal direction from the axis of the body and inserted until it reaches the base of the coracoid process. (c) The needle can be inserted toward the sensory branch of the suprascapular nerve passing the base of the coracoid by the method shown in panels (a, b) (From Matsumoto et al. [6], with permission)

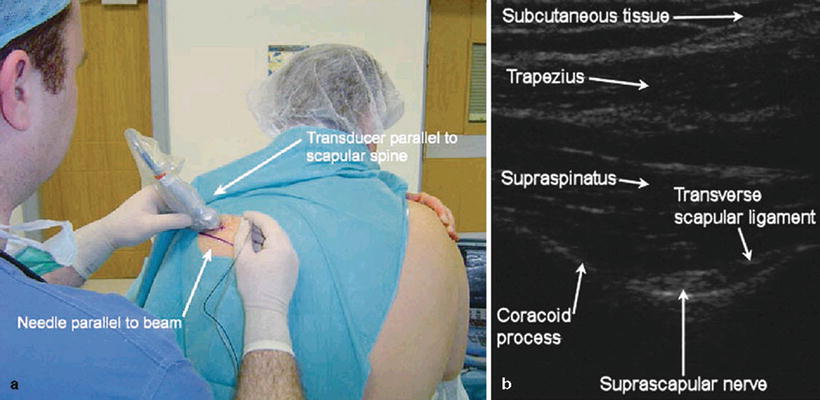

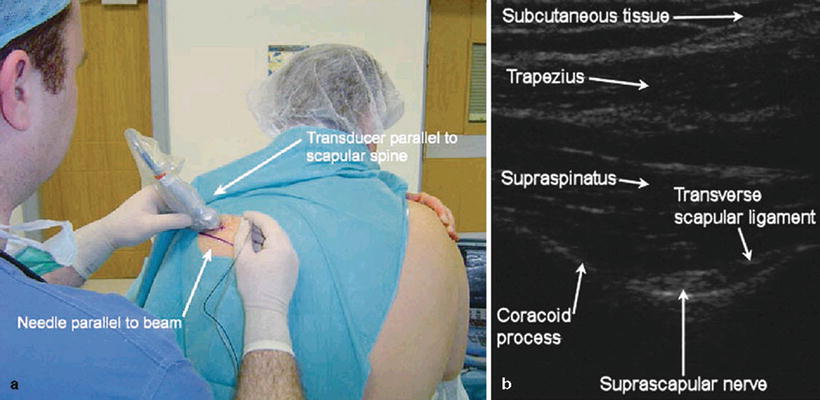

While the SSNB has been traditionally performed based on anatomic landmarks, imaging guidance utilizing fluoroscopy, CT, and ultrasound has been described [26, 31, 37, 38]. One author recommended using fluoroscopy to identify the suprascapular notch when performing the direct technique, especially when it is difficult to locate the suprascapular notch via the anatomic approach. The patient should be placed in the prone position with the fluoroscope slightly lateral to midline at the T2–3 level with a slight cephalocaudad tilt [31]. In a non-randomized controlled trial of 40 patients with chronic shoulder pain, Schneider-Kolsky et al. performed a CT-guided SSNB with a direct approach and reported improvement in SPADI scores at 30 min, 3 days, weeks, and 6 weeks post injection [26]. While these results were encouraging, Shanahan et al.’s randomized controlled trial failed to show any difference in pain, disability, or patient satisfaction between CT-guided and traditional nonimage-guided SSNBs [37]. Two case reports reported favorable results using ultrasound guidance. Harmon et al. described first placing the ultrasound transducer in a transverse orientation over the scapular spine (see Fig. 28.5) [38]. The transducer is then gradually moved in a cephalad and slightly lateral direction until the suprascapular notch and transverse scapular ligament are identified. The suprascapular nerve lies just inferior to the ligament. However, a subsequent cadaveric study revealed that the structure previously identified under ultrasound guidance as the transverse ligament was the fascia layer of the supraspinatus muscle [39]. Therefore, an ultrasound-guided SSNB appears to be an indirect technique with the injectate placed near the nerve in the suprascapular fossa, rather than a direct technique in the suprascapular notch as previously believed.

Fig. 28.5

(a) Ultrasound transducer and needle orientation for the ultrasound-guided suprascapular nerve block. (b) Transverse view of suprascapular fossa and scapular notch with a SonoSite ultrasound system and a 6–13-MHz linear transducer (From Harmon and Hearty [38], with permission)

The SSNB is considered a safe technique and is associated with few side effects and complications [1–12]. While pneumothorax is a possible serious complication, the incidence is less than 1 %. Furthermore, this complication has only been described with the direct technique in which the end of the needle is placed directly in the suprascapular notch and approximates the superior aspect of the lung [36]. In order to minimize this complication, Parris and colleagues suggest internally rotating the ipsilateral arm and placing the hand on the opposite shoulder in order to elevate the scapula away from the chest wall [12]. Most other complications described in the literature have been transient in nature and similar to minor complications associated with most other kinds of interventional procedures [1, 3–6, 9, 11, 12]. Goldner reported performing over 1,000 direct SSNBs, with the only occasional minor complication being temporary postinjection tenderness [34]. Dahan et al. reported performing over 2,000 indirect SSNBs and reported no significant complications other than a few vasovagal reactions and postinjection tenderness [4].