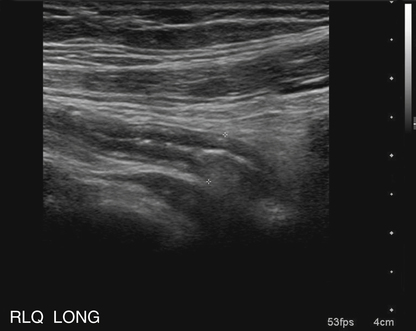

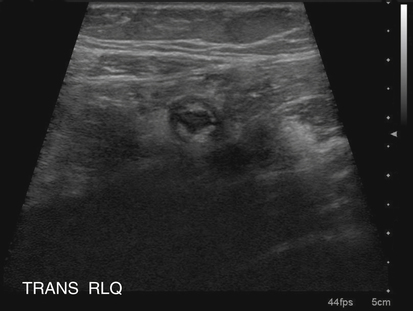

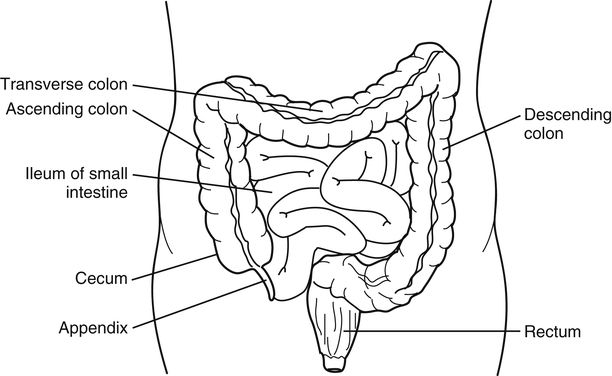

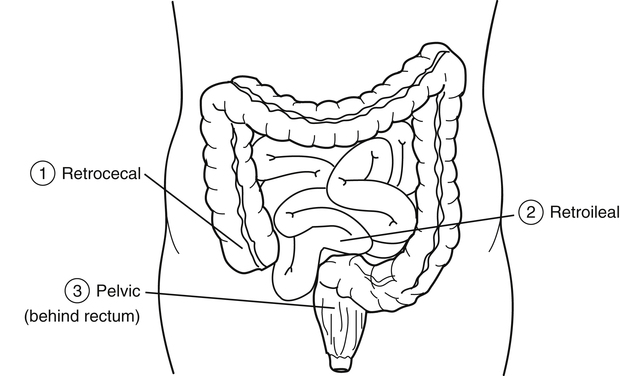

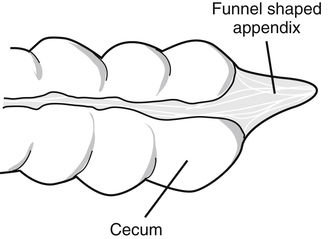

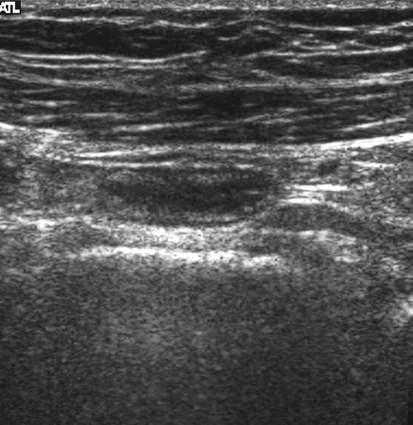

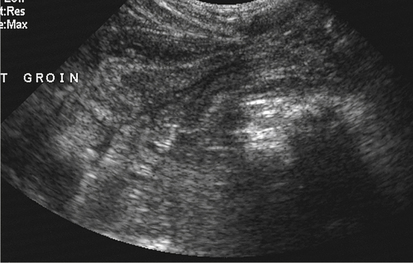

Kristy Stohlmann and Kathryn Kuntz Acute appendicitis is one of the most common diseases that necessitates emergency surgery and is the most common atraumatic surgical abdominal disorder in children 2 years old and older. Males and females have a lifetime appendicitis risk of 8.6% and 6.7%; the mortality rate in nonperforated appendicitis is less than 1%.1 Early diagnosis of appendicitis is essential to prevent perforation, abscess formation, and postoperative complications. A delay in diagnosis often occurs with young, pregnant, or elderly patients, increasing the risk of perforation. The mortality rate can be 5% in these patients.1,2 During the past 2 decades, sonography, along with nuclear medicine and computed tomography (CT), has been used in the diagnosis of appendicitis. Despite technologic advances, the diagnosis of appendicitis is still based primarily on patient history and physical examination.1,2 The appendix is a long, thin diverticulum that arises from the inferior tip of the cecum (Fig. 11-3). Although the average length of the appendix is 3 inches, it can measure 9 inches. The appendix usually has an anterior intraperitoneal location that, when inflamed, may come in contact with the anterior parietal peritoneum and cause RLQ pain. The appendix may be “hidden” from the anterior peritoneum 30% of the time when in a pelvic, retroileal, or retrocecal position (Fig. 11-4).3 The differing locations of the appendix can make sonographic imaging a challenge. The shape of the appendix also differs depending on the patient’s age. At birth, the appendix is funnel-shaped, which limits the chance for obstruction to occur. By age 2 years, the appendix assumes a more normal conic shape, which increases the chance for luminal obstruction (Figs. 11-5 and 11-6). Although the appendix itself is not necessary for survival, the lining of the appendix, composed of lymphatic tissue, is thought to play a specialized role in the immune system. Appendicitis usually results from an obstructing object, or obstructive disorder, within the appendix. The risk for an obstruction can be linked to diet or genetic predisposition. Generally, unhealthy diets, including decreased dietary fiber, along with increased refined carbohydrates (e.g., pure sugars and starches), can increase the incidence rate of appendicitis. A history of appendicitis in a first-degree relative is associated with a 3.5% to 10% relative risk. The strongest familial associations have been noted when children develop appendicitis at unusually young ages (birth to 6 years).4 Some cases of appendicitis have a different etiology. These less common cases begin with direct mucosal ulceration caused by a buildup of mucus within the appendix, sometimes called a mucocele, which leads to bacterial invasion and resultant appendicitis. Sonographically, a mucocele of the appendix is shown by a dilated, noncompressible appendix with an abnormal accumulation of debris (mucus) within the lumen. The appendiceal diameter can become very large, and the “onion sign” (sonographic layering of echogenic debris within a cystic mass) may be seen (see Table 11-1). TABLE 11-1 ∗May be present; accuracy of these findings alone is limited in the diagnosis of appendicitis. Regardless of the cause of appendicitis, the patient must seek immediate medical attention. If patients do not have symptoms, choose to ignore the symptoms, or cannot communicate their symptoms (e.g., infants and young children), rupture is a risk. Failure to receive medical attention within 36 hours is associated with an increased risk of rupture of the appendix, and the risk increases in ensuing 12-hour periods.5 A ruptured appendix places the patient at much greater risk for postsurgical complications. Rupture causes the bacteria-filled mucus to spill into the peritoneum and can lead to diffuse peritonitis, or abscess formation.6 When the appendix has ruptured, sonographic visualization is much more difficult because the lumen is no longer distended, and the anatomy is distorted by surrounding inflammation and adjacent abscess (see Table 11-1). The first classic symptom of appendicitis is periumbilical pain, followed by nausea, RLQ pain, and subsequent vomiting with fever.2 All of these symptoms are present in 50% of adult cases. Other adult cases and many pediatric cases may have more inconspicuous symptoms, such as irritability, lethargy, abdominal pain, anorexia, fever, or diarrhea, which make diagnosis more of a challenge. The most important clinical finding is RLQ pain with palpation. Physicians also use the quick release method to rule out appendicitis. The quick release is performed by applying pressure with the fingertips directly over the area of the appendix and then quickly letting go. With appendicitis, the patient usually has rebound tenderness (McBurney’s sign) associated with peritoneal irritation. Although an elevated WBC count (>10,000/mm3) can be an indicator for appendicitis, the accuracy of this test alone is limited. Vague abdominal pain that sometimes occurs with appendicitis may mimic several other GI diseases. It is important to obtain an accurate patient history to rule out other diseases, including gallbladder disease; acute pyelonephritis; urinary tract stone disease; infectious or inflammatory conditions of the cecum and ascending colon; and unusual diseases such as complicated ovarian cysts, cyst hemorrhage, and ovarian torsion.3 A pelvic examination or pelvic sonography should be performed in women with suspicious RLQ pain because some painful gynecologic conditions can mimic appendicitis. A pregnancy test for all women of childbearing age is also recommended to rule out ectopic pregnancy. Graded compression sonography is a rapid, noninvasive, and inexpensive means of imaging a normal or inflamed appendix. When inflamed, the appendix does not compress. The technique requires no patient preparation, and scanning can be performed at the most tender site, which enables correlation of imaging findings with patient symptoms. A high-frequency linear array transducer ranging from 7 to 12 MHz is most commonly used. Before scanning, the patient is asked to point with one finger to the place of maximal pain. Graded compression uses gradual pressure, with the transducer moving in a cephalad-to-caudad fashion to displace the normal gas-containing bowel loops for visualization of the inflamed appendix. This technique also helps to identify the location of an abnormally positioned appendix.6 The graded compression technique used to image the appendix has been proven to be of considerable value in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Compression aids in relocating normal bowel loops and interfering air away from the site of interest. In more difficult cases, a technique called posterior manual compression can be used in addition to graded compression.1,6 Posterior manual compression is performed by using both hands. The hand not holding the transducer is placed on the patient’s back, and pressure is applied upward in an anterior direction. At the same time, pressure is applied on the abdomen by the transducer in the posterior direction. This technique helps visualize the appendix when it is located in a deep position.6 Placing the patient in a left oblique lateral decubitus position may also be helpful in visualizing a retrocecal appendix. If the patient is unable to point to a specific area of pain, the sonographer must locate the appendix. Real-time scanning is initiated in the transverse plane and directed toward the cecal tip and the origin of the appendix. Scanning begins laterally in the iliac fossa, at the level of the umbilicus. Gradual pressure (graded compression) is applied with the transducer to compress bowel loops and express all gas and fluid contents away from the site of interest. The ascending colon is first identified as a gas-filled peristaltic structure with the sonographic appearance of bowel (i.e., an inner echogenic ring surrounded by five concentric bowel wall layers) (Fig. 11-7). The ascending colon is scanned caudally to its termination at the cecum. With the transducer in the transverse plane, the cecum is scanned inferiorly to its tip. The normal cecum and terminal ileum are easily compressible with moderate pressure. The terminal ileum is identified as a compressible peristaltic bowel segment adjacent to the cecum. The examination is continued inferiorly with identification of the psoas and iliacus muscles and the external iliac artery and vein.

Suspect Appendicitis

Anatomy and Physiology

Epidemiology

Pathology

Symptoms

Sonographic Findings

Appendicitis—classic symptoms

Periumbilical pain, followed by nausea, RLQ pain, and subsequent vomiting with fever; rebound tenderness (positive McBurney’s sign)

Primary findings: Noncompressible, nonperistaltic, blind-ended appendix with outer wall–to–outer wall AP measurement of >6 mm

Other Findings∗: Muscle wall AP measurement >2 mm; echogenic shadowing appendicolith; hyperemia with increase in color Doppler; inflamed, echogenic periappendiceal fat; pericecal or perivesical free fluid (ascites); complex mass representing an abscess

Appendicitis—other symptoms

Irritability, lethargy, abdominal pain, anorexia, or diarrhea∗

Rupture

Same as or indistinguishable from non-ruptured appendicitis.

Variable; distorted anatomy with or without distended appendiceal lumen; vague hypoechoic or complex periappendiceal mass; target sign with inhomogeneous or missing layers in wall; inhomogeneous pericecal or perivesical mass without peristalsis or free fluid in abdomen

Mucocele

Varies from asymptomatic to possible pain in the right lower abdominal quadrant, weight loss, nausea, vomiting, change in bowel habits, anemia, and hematochezia.

Dilated appendiceal lumen; cystic mass in expected region of appendix (with possible sonographic layering called the “onion sign”); possible internal echogenicity; lack of appendiceal wall thickening

Associated laboratory values for appendicitis

Elevated white blood cell count of >10,000/mm3∗

Clinical Presentation

Sonographic Findings

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Suspect Appendicitis