KEY FACTS

Longitudinal type

Most common (70% to 80%) type of temporal bone fractures; results from blows to the temporoparietal region.

Most common (70% to 80%) type of temporal bone fractures; results from blows to the temporoparietal region.

Results in conductive hearing loss secondary to ossicular chain dislocations (most common: incudostapedial [distance between these ossicles is >2 mm] and malleoincudal dislocations).

Results in conductive hearing loss secondary to ossicular chain dislocations (most common: incudostapedial [distance between these ossicles is >2 mm] and malleoincudal dislocations).

Tympanic membrane is often perforated, increased incidence of postfracture cholesteatoma.

Tympanic membrane is often perforated, increased incidence of postfracture cholesteatoma.

Facial palsy (10% to 20%) is delayed (due to swelling of descending facial nerve and entrapment within bone canal) and generally resolves spontaneously.

Facial palsy (10% to 20%) is delayed (due to swelling of descending facial nerve and entrapment within bone canal) and generally resolves spontaneously.

Air in the temporomandibular joint is an indirect sign of temporal bone fracture.

Air in the temporomandibular joint is an indirect sign of temporal bone fracture.

Air in the labyrinth is indicative of underlying fracture.

Air in the labyrinth is indicative of underlying fracture.

Transverse type

Second most common (10% to 20%) type of temporal bone fracture (some authors believe that mixed or complex fractures are more common than either).

Second most common (10% to 20%) type of temporal bone fracture (some authors believe that mixed or complex fractures are more common than either).

Results from frontal or occipital blows.

Results from frontal or occipital blows.

Produces sensorineural hearing loss and vertigo due to involvement of the otic capsule and/or transaction/concussion of 8th cranial nerve.

Produces sensorineural hearing loss and vertigo due to involvement of the otic capsule and/or transaction/concussion of 8th cranial nerve.

Facial palsy is more common than with transverse fractures and usually is permanent and due to nerve transection.

Facial palsy is more common than with transverse fractures and usually is permanent and due to nerve transection.

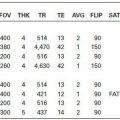

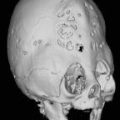

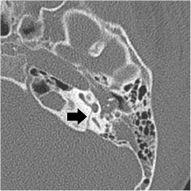

FIGURE 30-1. Axial computed tomography (CT) shows longitudinal fracture (arrow) and separation of malleus and incus.

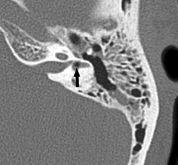

FIGURE 30-2. Axial CT, in a different patient, shows air (arrow) in vestibule due to a fracture.

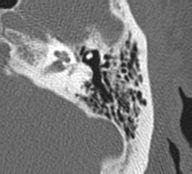

FIGURE 30-3. Axial CT, in a different patient, shows missing incus due to complete dislocation. Only the head of the malleus is seen.

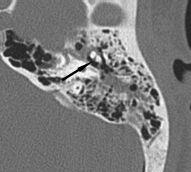

FIGURE 30-4. Axial CT, in a different patient, shows mild malleoincudal separation (arrow) and air cell opacification.

FIGURE 30-5. Axial CT, in a different patient, shows transverse fracture (arrow) extending to basal turn of cochlea.

SUGGESTED READING

Swartz JD. Temporal bone trauma. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 2001;22:219–228.

KEY FACTS

Most common posterior fossa tumor in adults and second most common intracranial extra-axial tumor after meningioma in adults.

Most common posterior fossa tumor in adults and second most common intracranial extra-axial tumor after meningioma in adults.

75% to 80% of masses in the cerebellopontine angle cistern are vestibular schwannomas.

75% to 80% of masses in the cerebellopontine angle cistern are vestibular schwannomas.

They arise from Scarpa ganglion (glial-Schwann cell junction) in the superior division of the vestibular nerve.

They arise from Scarpa ganglion (glial-Schwann cell junction) in the superior division of the vestibular nerve.

They are more common in females aged 40 to 60 years.

They are more common in females aged 40 to 60 years.

Bilateral eighth nerve schwannomas = NF-2.

Bilateral eighth nerve schwannomas = NF-2.

Most common symptoms: sensorineural hearing loss, tinnitus, headache, and disequilibrium.

Most common symptoms: sensorineural hearing loss, tinnitus, headache, and disequilibrium.

Facial nerve palsy is uncommon as this nerve is fairly resistant to pressure.

Facial nerve palsy is uncommon as this nerve is fairly resistant to pressure.

5% to 22% of vestibular schwannomas are atypical by imaging and have associated arachnoid cysts or central necrosis or are partially or completely cystic.

5% to 22% of vestibular schwannomas are atypical by imaging and have associated arachnoid cysts or central necrosis or are partially or completely cystic.

Main differential diagnosis: meningioma, facial nerve schwannoma, metastasis, viral infection (Ramsay Hunt syndrome), lipoma (low signal on fat suppression magnetic resonance (MR) images)

Main differential diagnosis: meningioma, facial nerve schwannoma, metastasis, viral infection (Ramsay Hunt syndrome), lipoma (low signal on fat suppression magnetic resonance (MR) images)

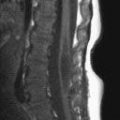

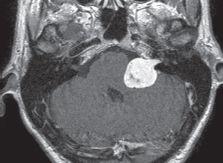

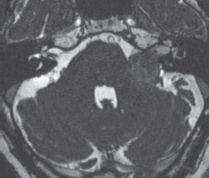

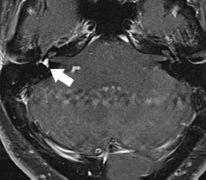

FIGURE 30-6. Axial postcontrast T1 shows typical “ice cream cone” shape of large and mostly homogeneous enhancing left vestibular schwannomas.

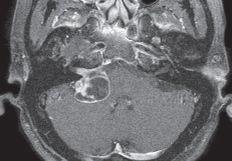

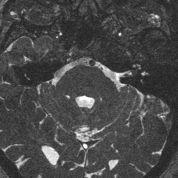

FIGURE 30-7. Axial postcontrast T1, in a different patient, shows a mostly cystic right vestibular schwannoma.

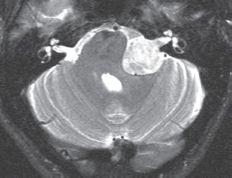

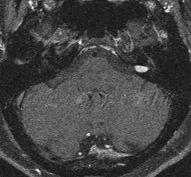

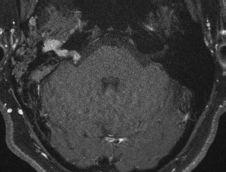

FIGURE 30-8. Axial T2, in a different patient, shows a large and bright tumor.

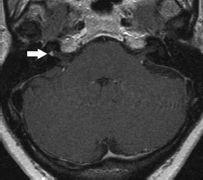

FIGURE 30-9. Axial constructive interference in steady state (CISS) image, in a different patient, shows the left-sided schwannoma to be dark; note the decreased signal from fluid in inner ear structures probably due to increased proteins.

FIGURE 30-10. Axial CISS image, in a different patient, shows a small left tumor in fundus of internal auditory canal and probably extending to the basal turn of the cochlea at insertion of modiolus.

FIGURE 30-11. Axial postcontrast T1, in a different patient, shows an enhancing left intracanalicular schwannoma.

FIGURE 30-12. Axial postcontrast T1 image, in a different patient, shows tiny tumor (arrow) in fundus of the right internal auditory canal.

FIGURE 30-13. Axial postcontrast T1 image in a different patient with a purely intravestibular schwannoma (arrow).

SUGGESTED READING

Davidson HC. Imaging evaluation of sensorineural hearing loss. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2001;22:229–249.

KEY FACTS

Account for 5% of facial nerve palsies, particularly unilateral (the remainder are of viral or posttraumatic etiology).

Account for 5% of facial nerve palsies, particularly unilateral (the remainder are of viral or posttraumatic etiology).

Onset of facial nerve palsy is slow and progressive.

Onset of facial nerve palsy is slow and progressive.

Tend to arise in the geniculate ganglion but may involve any of its segments.

Tend to arise in the geniculate ganglion but may involve any of its segments.

Identification of extension along the labyrinthine segment of the facial nerve is important in making the correct presurgical diagnosis as it is only schwannomas that result in significant thickening and enhancement in this region.

Identification of extension along the labyrinthine segment of the facial nerve is important in making the correct presurgical diagnosis as it is only schwannomas that result in significant thickening and enhancement in this region.

Main differential diagnosis: facial nerve hemangioma, perineural tumor spread, vestibular schwan-noma, viral neuritis (Bell palsy and Ramsay Hunt syndrome), and meningioma.

Main differential diagnosis: facial nerve hemangioma, perineural tumor spread, vestibular schwan-noma, viral neuritis (Bell palsy and Ramsay Hunt syndrome), and meningioma.

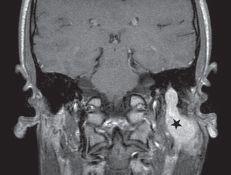

FIGURE 30-14. Coronal postcontrast T1 shows enhancing schwannoma involving the descending and intraparotid (star) portions of cranial nerve VII.

FIGURE 30-15. Axial postcontrast T1, in the same patient, shows the tumor in the mastoid portion (arrow) of the facial nerve.

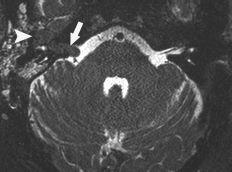

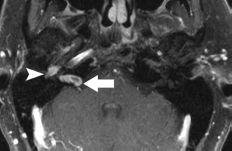

FIGURE 30-16. Axial CISS image, in a different patient, shows dark signal in a facial nerve tumor involving the ICA (arrow) and the region of geniculate ganglion (arrowhead).

FIGURE 30-17. Corresponding postcontrast T1 shows enhancement throughout the tumor.

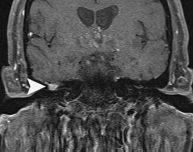

FIGURE 30-18. Axial postcontrast T1, in a different patient, shows schwannoma in the internal auditory canal (arrow) and geniculate ganglion (arrowhead).

FIGURE 30-19. Coronal postcontrast T1, in the same patient as 30-18, shows tumor in geniculate ganglion (arrowhead).

SUGGESTED READING

Phillips CD, Bubash LA. The facial nerve: anatomy and common pathology. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2002;23: 202–217.

ENLARGED ENDOLYMPHATIC SAC (LARGE VESTIBULAR AQUEDUCT) SYNDROME

ENLARGED ENDOLYMPHATIC SAC (LARGE VESTIBULAR AQUEDUCT) SYNDROME

KEY FACTS

1% of patients with congenital sensorineural hearing loss have abnormalities detected by imaging studies; the most commonly recognized one is probably a large vestibular aqueduct.

1% of patients with congenital sensorineural hearing loss have abnormalities detected by imaging studies; the most commonly recognized one is probably a large vestibular aqueduct.

Normal vestibular aqueduct extends from the vestibule to the posterior aspect of the petrous bone and contains the endolymphatic duct whose function is equilibration of endolymphatic fluid pressure.

Normal vestibular aqueduct extends from the vestibule to the posterior aspect of the petrous bone and contains the endolymphatic duct whose function is equilibration of endolymphatic fluid pressure.

CT: dilated vestibular aqueduct (vestibular aqueduct should be no wider than a semicircular canal or more than 1.5 mm at its midpoint).

CT: dilated vestibular aqueduct (vestibular aqueduct should be no wider than a semicircular canal or more than 1.5 mm at its midpoint).

A large vestibular aqueduct may be associated with cochlear anomalies (from Mondini to absence of the modiolus).

A large vestibular aqueduct may be associated with cochlear anomalies (from Mondini to absence of the modiolus).

Enlargement of the endolymphatic sac may occur in the presence of normal-sized aqueduct, and it may present as a mass in the cerebellopontine angle region and is better seen on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Enlargement of the endolymphatic sac may occur in the presence of normal-sized aqueduct, and it may present as a mass in the cerebellopontine angle region and is better seen on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Fluid levels and occasional contrast enhancement may be seen within the large endolymphatic sac.

Fluid levels and occasional contrast enhancement may be seen within the large endolymphatic sac.

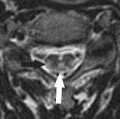

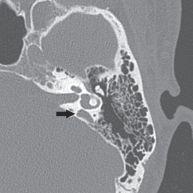

FIGURE 30-20. Axial CT shows large vestibular aqueduct (arrow), large vestibule (star), and dysplastic cochlea with absent modiolus and abnormal middle and apical turns.

FIGURE 30-21. Axial CT, in a different patient, shows moderately dilated vestibular aqueduct (arrow).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree