Chapter 13 The Bronchi

EVALUATION

Bronchial Anomalies

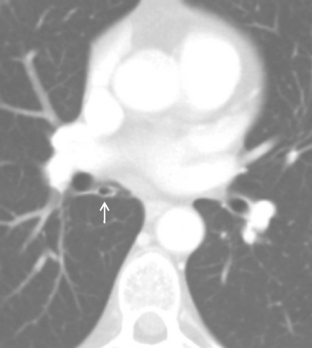

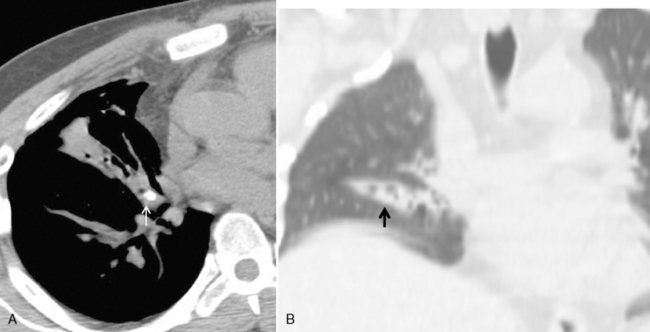

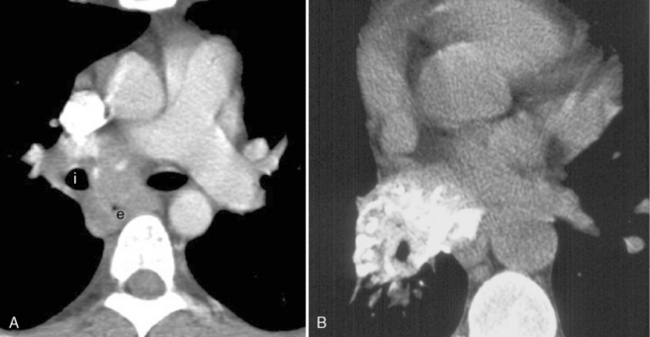

Bronchial anomalies include abnormal origin, supernumerary bronchi, bronchial atresia, and bronchial isomerism. A cardiac bronchus is a supernumerary bronchus that is seen in 0.1% of population (Box 13-1). The bronchus arises from the medial aspect of the bronchus intermedius and extends medially toward the heart (Fig. 13-1). The bronchus may end in a blind stump or supply a segment of lung; this is mostly an incidental finding. However, the blind ending bronchus may be a potential reservoir of infection and lead to recurrent infections and hemoptysis. If the patient is symptomatic, surgical resection is the treatment. Other bronchial anomalies are discussed in Chapter 2.

Box 13-1 Cardiac Bronchus

Supernumerary bronchus from the medial aspect of the bronchus intermedius

May end blindly or supply a segment of lung

Blind pouch may predispose to recurrent infection and hemoptysis

ENDOBRONCHIAL LESIONS

Broncholithiasis

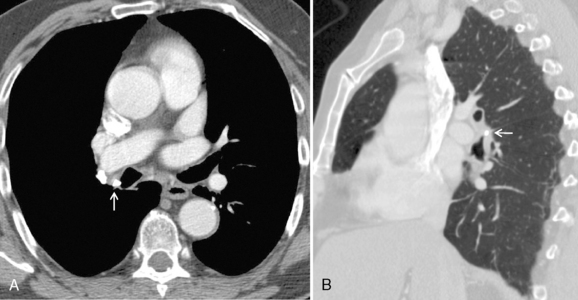

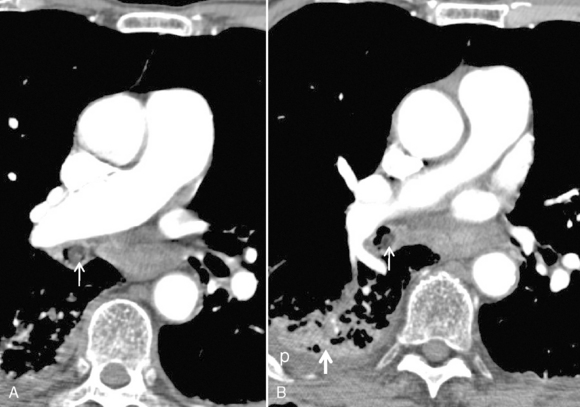

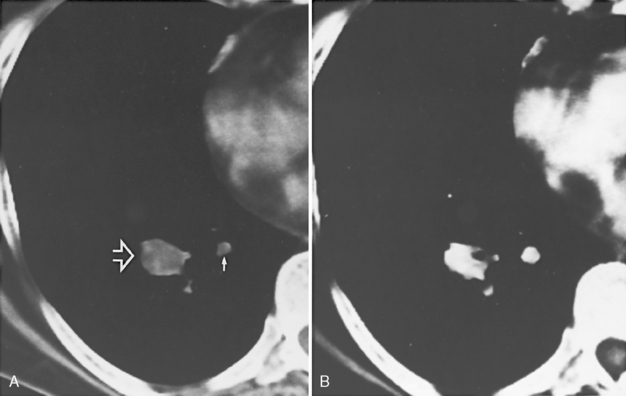

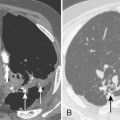

Radiographically, the key finding is a calcified endobronchial lesion or peribronchial lymph node without associated soft tissue, which may be associated with findings of bronchial obstruction such as atelectasis, postobstructive pneumonia, and air trapping (Box 13-2 and Fig. 13-2).

Box 13-2 Findings for Broncholithiasis

Calcified lymph node with peribronchial location or erosion into the bronchus

Secondary findings of obstruction

Aspiration of a Solid Foreign Body

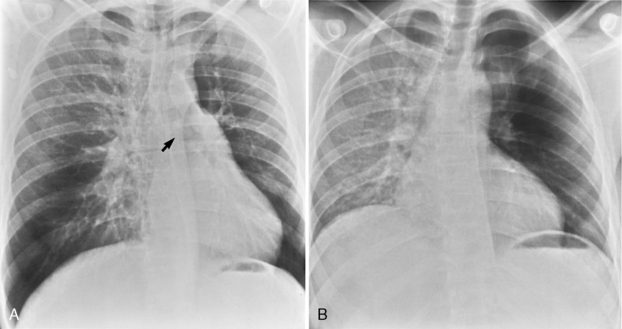

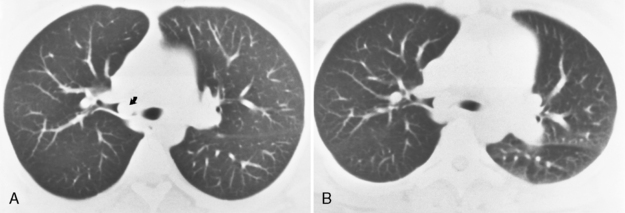

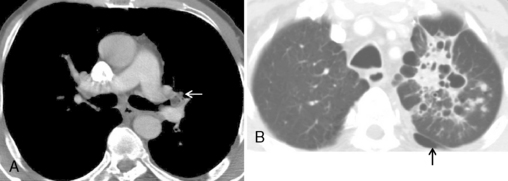

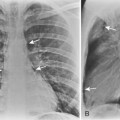

Air trapping is the most common finding after acute aspiration of a foreign body because of a check-valve mechanism of bronchial obstruction. Air trapping may not be apparent on inspiration, but it is apparent on expiratory radiographs, expiratory CT scans, and decubitus chest radiographs. On expiration, the lung becomes more opaque. Similarly, on decubitus radiographs, the dependent lung is hypoinflated and therefore more opaque. If air trapping is present, the obstructed lobe or lung will remain lucent and not decrease in volume on expiration, or if the affected lung is in a more dependent position, the mediastinum will shift away from the side of air trapping (Fig. 13-3). Hypoxic vasoconstriction may develop within an obstructed lobe or lung; it manifests radiographically as a hyperlucency of the lung and attenuation of the pulmonary vessels (Fig. 13-4). In adults, aspirated foreign bodies may remain clinically silent. In cases of chronic obstruction, atelectasis, recurrent pneumonia, intrabronchial mass, hemoptysis, or bronchiectasis may develop (Box 13-3). CT can identify the endobronchial site of an aspirated foreign body and demonstrate air trapping. A high-density foreign body suggests bone, metallic foreign body, or a tooth (Fig. 13-5). Vegetable material has soft tissue density and occasionally has fat density (Fig. 13-6). MRI may be helpful in identifying aspirated peanuts, which characteristically have a high-intensity signal on T1-weighted images.

Bronchial Neoplasms

Hamartoma

Hamartoma is the most common benign tumor of the lung, accounting for 77% of tumors in a series by Arrigoni. Approximately 3% to 10% of these tumors arise within the bronchi. Bronchial hamartomas are slow-growing tumors seen within large bronchi. They contain normal components of bronchi, such as cartilage, fat, fibrous tissue, and epithelium, arranged in a disorganized fashion. The appearance of fat or characteristic popcorn calcification on CT suggests the diagnosis. Calcification is present in approximately 25% of hamartomas and is more common in larger lesions. Signs of bronchial obstruction such as collapse or recurrent pneumonia may be seen (Box 13-4 and Fig, 13-7).

Box 13-4 Bronchial Hamartomas

Most in the lung periphery; a few found within large bronchi

CT identification of fat aids diagnosis

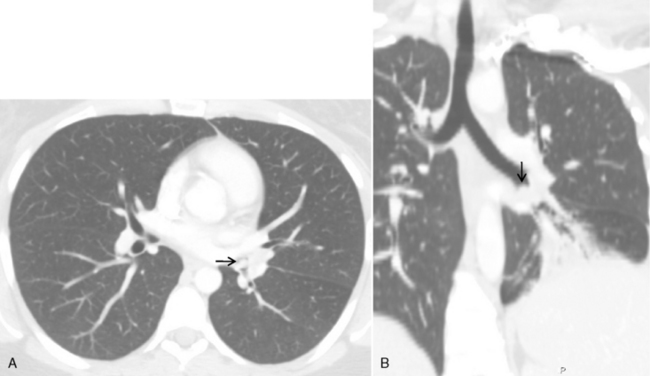

Carcinoid Tumors

The main clinical differences among typical carcinoid, atypical carcinoid, and small cell carcinoma lie in the prevalence of metastases and in the prognosis (Box 13-5). Typical carcinoids manifest in patients at an earlier age, usually 40 to 50 years. They are usually smooth, round, well-defined, small (<2.5 cm) masses that arise in the central bronchi (Fig. 13-8). There is a predilection for women, and they are not associated with smoking. Most carcinoids arise with the main, lobar, or segmental bronchi. Only 10% of carcinoids are seen in the periphery of the lung (Fig. 13-9). These tumors have an excellent prognosis, with 5-year survival rates of 90% to 95%. Atypical carcinoids are diagnosed in patients between 50 and 60 years old and are more common in men and smokers. They tend to be larger at diagnosis, may be centrally or peripherally located, and have a tendency to metastasize to hilar or mediastinal lymph nodes (Fig. 13-10). The 5-year survival rate is between 50% and 70%. Small cell carcinoma manifests in patients between 60 and 70 years old and is four times more common in men. The tumors commonly metastasize and have a strong association with smoking. These extremely malignant tumors are most often associated with bulky hilar and mediastinal adenopathy. A small, peripheral nodule representing the primary tumor is often found on CT. These tumors carry a poor prognosis.

Box 13-5 Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Lung

TYPICAL CARCINOID

Peak occurrence between 40 and 50 years of age

Round, smooth, well-defined nodule

Location: 90% in central bronchi, 10% in lung periphery

ATYPICAL CARCINOID

Peak occurrence between 50 and 60 years of age

Larger nodule than the typical carcinoid

Central or peripheral location

Metastasis to hilar and mediastinal nodes

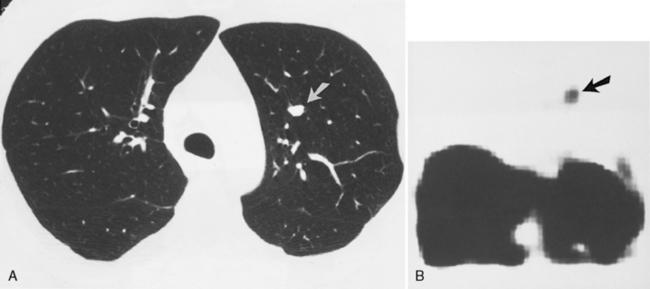

Imaging studies may identify several distinguishing features of carcinoid tumors (Box 13-6). They are well-defined endobronchial tumors that may have extrabronchial extension. Calcification is seen in up to 40% of these tumors on CT (see Fig. 13-8). These highly vascular tumors demonstrate marked contrast enhancement with iodinated contrast on CT (see Fig. 13-9) and with gadolinium on MRI. Somatostatin receptors have been identified in a wide variety of human tumors with neuroendocrine characteristics, including carcinoid tumors. 123I-Tyr3-octreotide and 111In-octreotide are radionuclide-coupled somatostatin analogues that can be used to visualize somatostatin receptor–bearing tumors (Fig. 13-11). Known tumor sites have been visualized in 86% of patients in whom histologically confirmed carcinoids were present.

Box 13-6 Imaging Features of Carcinoid Tumors

Nodule or mass within a central bronchus associated with atelectasis, pneumonia, or bronchiectasis

Occur as a peripheral, solitary pulmonary nodule in 10% of patients

Mucoepidermoid Tumors

Mucoepidermoid tumors are uncommon, representing 0.2% of all lung tumors and 1% to 5% of bronchial tumors. These tumors resemble salivary gland tumors, and as the name implies, they contain squamous and mucus-secreting columnar cells. The mean age of patients at presentation is 36 years. There is no sex predilection, and smoking is not a risk factor. Mucoepidermoid tumors of the central airways may be high- or low-grade malignancies. The radiograph usually shows a focal endobronchial mass within a large central airway, and it may be associated with bronchial obstruction (Fig. 13-12).

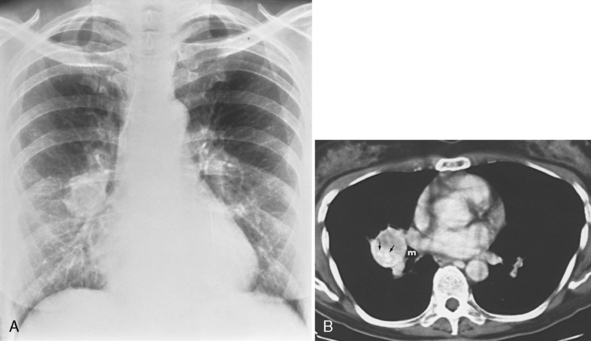

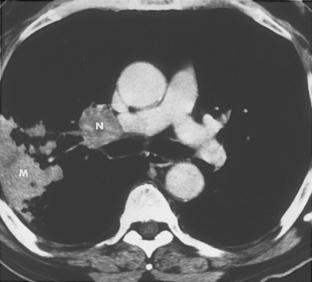

FIBROSING MEDIASTINITIS

Patients with fibrosing mediastinitis most often have cough, dyspnea, and hemoptysis. The most common radiologic finding is widening of the mediastinum and replacement of mediastinal fat by soft tissue density (Box 13-7). Calcification or calcified nodes may be identified within the mediastinal fibrosis, particularly on CT (Fig. 13-13). The mediastinal fibrosis typically encases and narrows affected mediastinal and hilar structures, including the bronchi. Contrast-enhanced CT or MRI is necessary to assess the vascular patency of the superior vena cava and the pulmonary veins and arteries.

Box 13-7 Radiographic Features of Fibrosing Mediastinitis

Replacement of mediastinal fat with soft tissue density of fibrosis

Calcification within mediastinal fibrosis and nodes

Encasement and narrowing of hilar and mediastinal structures

ESOPHAGOTRACHEOBRONCHIAL FISTULAS

Esophagotracheobronchial fistulas may be congenital or acquired (Box 13-8). Congenital esophagotracheobronchial fistulas are discussed in Chapter 2. Most acquired fistulas result from tumors of the esophagus, tracheobronchial tree, thyroid gland, and mediastinal nodes. Infection, trauma, and radiation are the chief causes of nonmalignant esophagotracheobronchial fistulas. Infections include histoplasmosis, tuberculosis, actinomycosis, and syphilis. Esophageal Crohn’s disease is also a cause of fistula. Erosion of calcareous particles from peribronchial lymph nodes in which the infectious process is no longer active can also lead a fistula, particularly in cases of histoplasmosis.

The typical complaint of these patients is a strangulating sensation occurring immediately after ingestion of solids or liquids. Routine chest radiography does not disclose the presence of the fistula, but may reveal pneumonia or bronchiectasis related to recurrent aspiration pneumonias, particularly in the lower lobes. Occasionally, a nasogastric tube entering the tracheobronchial tree through the esophageal orifice is seen. Early diagnosis can be established with the judicious use of a contrast esophagogram (Fig. 13-14). High-osmolar contrast should be avoided because of the risk of pulmonary edema if contrast reaches the lungs. CT scan is useful in demonstrating the fistula and in evaluating causative pathology and associated findings and complications (Fig. 13-15

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

700 Hounsfield units (HU) and window width of 1000 to 1500 HU is recommended. Modern CT scanners allow retrospective reconstruction of HRCT images from data acquired for regular chest CT. Paired inspiratory and expiratory scans performed at identical table levels are used to evaluate bronchomalacia and air trapping in patients with small airways disease, such as obliterative bronchiolitis. Measurement of attenuation values is useful in identifying fat in hamartomas and calcification in endobronchial hamartomas, chondromas, carcinoid tumors, and broncholiths. CT pixel histogram analysis allows measurement of fat not seen macroscopically.

700 Hounsfield units (HU) and window width of 1000 to 1500 HU is recommended. Modern CT scanners allow retrospective reconstruction of HRCT images from data acquired for regular chest CT. Paired inspiratory and expiratory scans performed at identical table levels are used to evaluate bronchomalacia and air trapping in patients with small airways disease, such as obliterative bronchiolitis. Measurement of attenuation values is useful in identifying fat in hamartomas and calcification in endobronchial hamartomas, chondromas, carcinoid tumors, and broncholiths. CT pixel histogram analysis allows measurement of fat not seen macroscopically.